The forgotten history of an American shrine

Common-place asks Scott Casper, whose Sarah Johnson’s Mount Vernon: The Forgotten History of an American Shrine was recently published by Hill & Wang, “how did you come to see that the story of Mount Vernon was an untold chapter of African American history central to the ways we imagine America itself?”

In the fall of 1998, I was doing research for a different sort of project about the ways Americans imagined their presidents’ families and domestic lives prior to the advent of radio or television. Among many sorts of sources, I was collecting evidence of people’s visits to presidents’ homes. Mount Vernon was far and away the most popular, during and especially after George Washington’s lifetime. Thousands of people went there every year; I read more than a hundred accounts spanning the nineteenth century. One of those visitors introduced me to Sarah Johnson, although I didn’t realize it at the time.

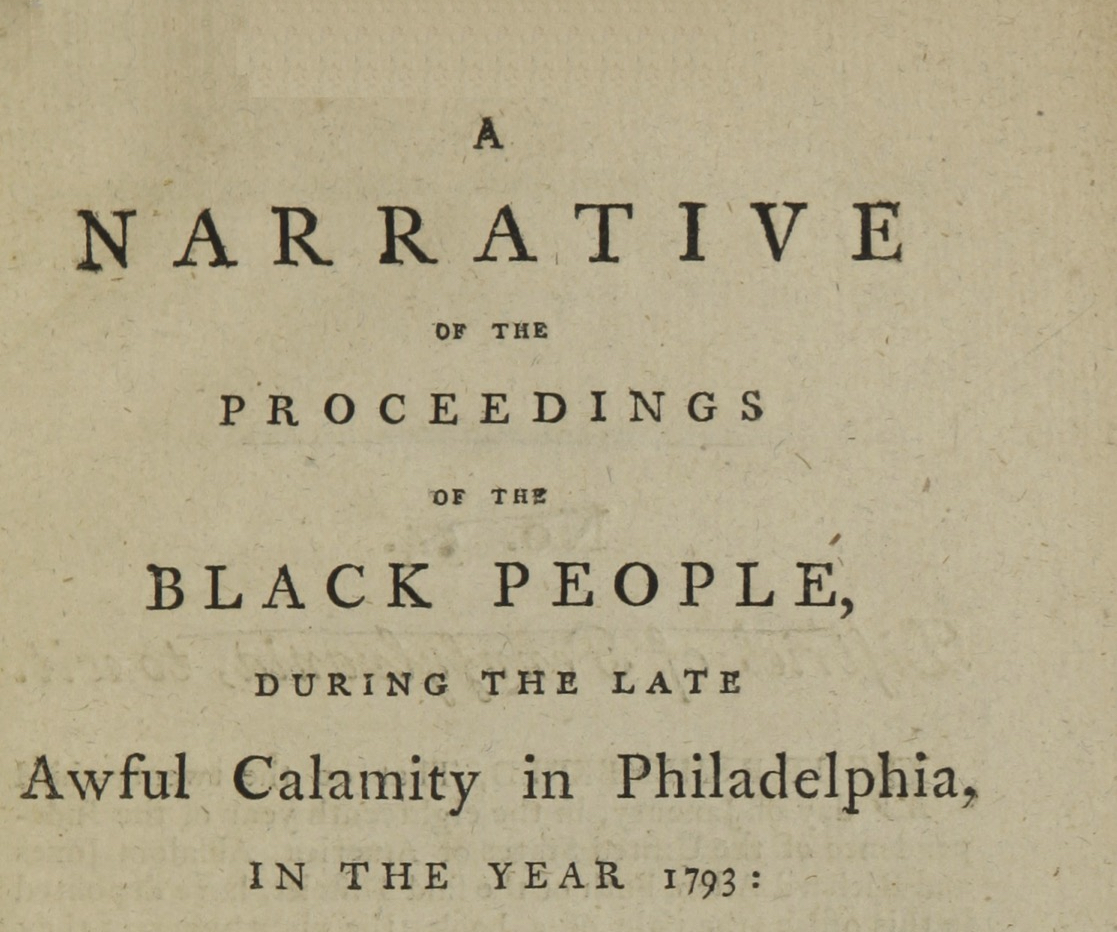

On September 4, 1865, the northern writer and abolitionist John Townsend Trowbridge stopped at Mount Vernon as part of a southern tour. Five months after Appomattox, Trowbridge had a contract with a northern publisher for a travel book about the defeated South. It came as no surprise to me, given the work of historian David Blight and others on Civil War memory, that Trowbridge depicted slaveowners as morally indefensible, freedpeople as industrious and heroic, and the abjection of the former Confederacy as just punishment for slavery and rebellion and as a starting ground for a new South. It also came as no surprise that Trowbridge saw African Americans working at Mount Vernon, because dozens of other travelers also recounted seeing black people there.

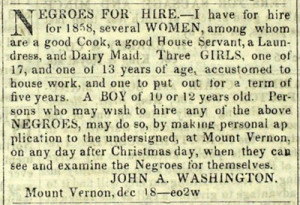

The surprise was that Trowbridge recounted his conversation with one of these black workers, complete with dialogue. She was a young woman, twenty years old, with a husband and four-year-old son. Trowbridge encountered her “industriously scrubbing over a tub” and described her as “intelligent and cheerful.” According to this young woman, she had formerly belonged to John A. Washington, who “kept me hired out” because he could make more money off her that way. She said that the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA) had brought her back as an employee after the war and that she now earned seven dollars a month, “a heap better ‘n no wages at all!” In her words, “The sweat I drap into this yer tub is my own; but befo’e, it belonged to John A. Washington.” Trowbridge didn’t get her meaning at first, so she elaborated, “You know, the Bible says every one must live by the sweat of his own eyebrow. But John A. Washington, he lived by the sweat of my eyebrow. I alluz had a will’n mind to work, and I have now; but I don’t work as I used to; for then it was work to-day and work to-morrow, and no stop.” Mount Vernon, formerly a slave plantation, had become an icon of emancipation.

At first, I thought that this episode fit right into the book I thought I was writing: it showed how white Americans like Trowbridge read their own ideas (in this case, about race) onto presidential homes (in this case, Mount Vernon). A magazine article twenty-two years later, in which a southern traveler recounted her own meeting with a woman selling milk at Mount Vernon, seemed the perfect bookend. In that piece, Sophie Bledsoe Herrick described the MVLA employee as a totem of Old South hospitality. The milk usually cost “Fi’ cents a glass,” said the woman, “onless, ladies, you will kindly accept it from the ‘sociation.” Servants like this one made visitors feel like Washington’s guests, not participants in a commercial transaction. They melted away the distance between slavery days and the present. Here, I thought, was marvelous evidence of what Blight describes in Race and Reunion: white Americans’ shift from “emancipationist” to “reconciliationist” notions of the Civil War, as white people put the Civil War behind them, romanticized the Old South, and cast African Americans anew as faithful servants (and slavery as picturesque paternalism).

In other words, visitors’ accounts seemed to support a historiographical interpretation that I already knew well. They dovetailed too with a lot of the revisionist work then coming out about historic preservation—scholarship that emphasized the political roots of preservation and the ways the managers of historic sites perpetuated now-antiquated views of slavery. For more than a century, the history of American historic preservation has been written about (and often by) the elite women and men at the center of the story, the people who saved places like Mount Vernon from dilapidation and speculation. But in the past decade or so, historians have told another sort of story, about the often conservative political agendas of those preservationist pioneers.

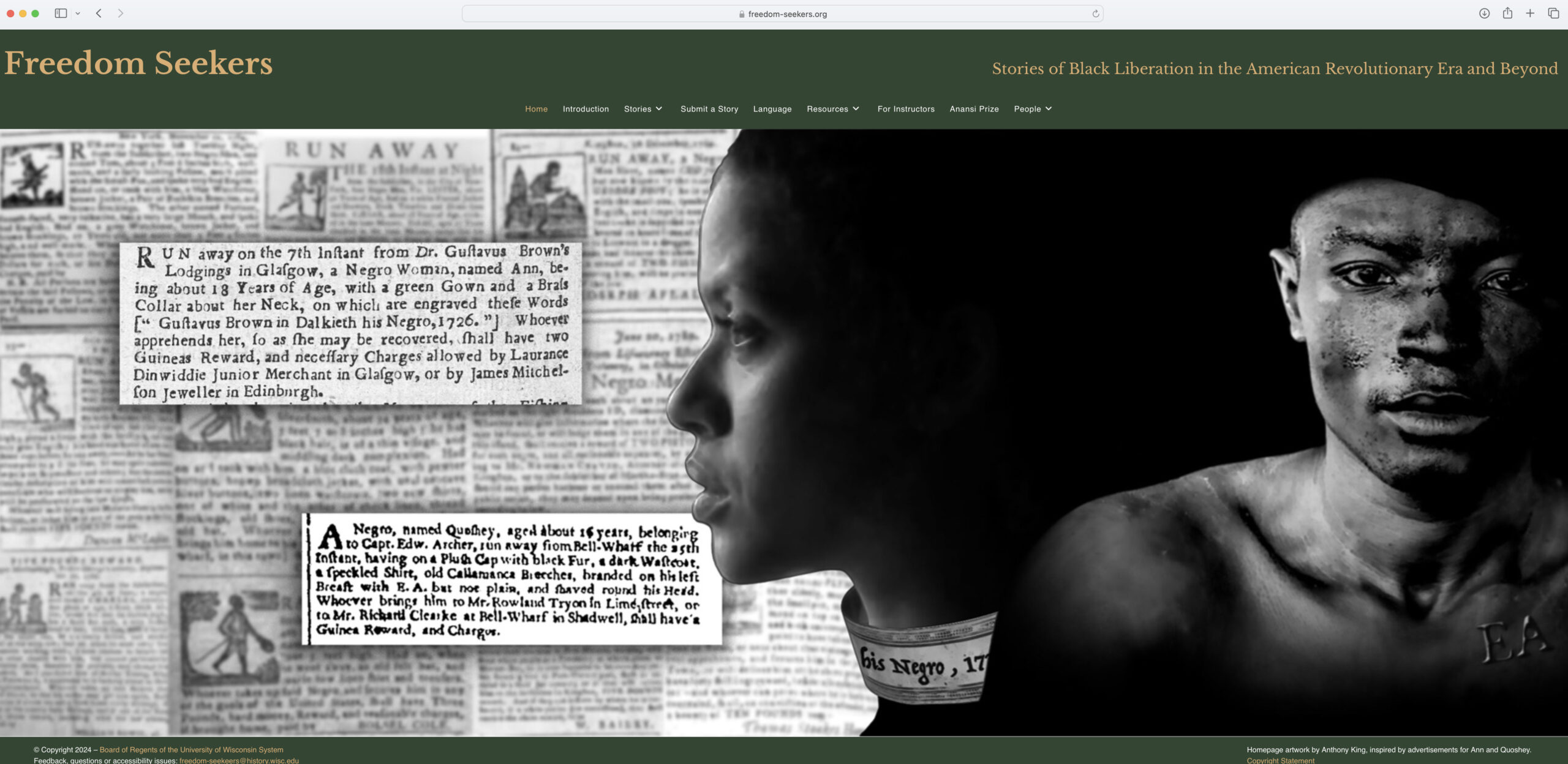

At the same time, sociologists and anthropologists have done another kind of work: analyzing the performances and presentations of history at such current-day sites as Plimouth Plantation, Colonial Williamsburg, and former southern plantations. These scholars interview interpreters and other front-line employees to consider their perspective on the history they presented. As I read this work, I started asking different questions about the women John Trowbridge and Sophie Herrick spoke with. What was it like to be on their side of the exchange? What did Mount Vernon’s employees make of the visitors and of their own presence at this American shrine? And how did Mount Vernon look through their eyes—not just as African Americans, but also as the people whose home it became long after George Washington died?

The first question was more practical: how could I tell that story for people who lived and died more than a century ago? Looking at two sorts of records began to persuade me that it might be possible. First, the United States census: according to the 1870 census, a twenty-five-year-old employee named Sarah Johnson lived with her nine-year-old son, Smith, at Mount Vernon. The ages matched; she could have been the person Trowbridge interviewed five years before. Second, the MVLA’s own annual reports and council minutes, which listed the employees annually from the 1870s on: there was Sarah Johnson, throughout the 1870s and 1880s and until 1892. Based on descriptions of her work, I soon realized that Trowbridge and Herrick had been speaking to the same person, twenty-two years apart.

This discovery led to more questions: how much could I learn about this woman? At first it became a detective story, a puzzle to piece together. Thanks to Mount Vernon’s remarkable archive, which includes the diaries and journals of John Augustine Washington (the last Washington family member to own the place) as well as the voluminous records of the MVLA itself, I figured out that Sarah had been born there in 1844 as a slave; that Washington had indeed hired her out in the late 1850s; and that she returned after the Civil War and worked there for twenty-seven years, steadily rising in authority, esteem, and pay until she retired in 1892. Thanks to the Fairfax County Courthouse Archives and other records in public sources, I learned that she had bought land in the late 1880s—four acres that had once belonged to her former owner and before him, to George Washington. It was potentially a great story.

And it was more than just one woman’s story. Immersed in the archives, I came to see Sarah as part of a community of African American families who lived and worked at Mount Vernon through the nineteenth century. Reconstructing those kin connections through national censuses, slave lists, wills, and other documents was critical. About two hundred slaves inhabited Mount Vernon from 1815 to 1861; the MVLA’s post-Civil War employees came mostly from this group. (To keep all the names straight, I created my own “census” of Mount Vernon’s enslaved population after 1815.) Equally important was placing these people within Mount Vernon’s geography and infrastructure across the nineteenth century, for example as this once-isolated plantation became increasingly connected to nearby Alexandria by roads, steamboats, and eventually electric streetcars. (To keep all the places straight, I filled an office wall with maps and plats of Mount Vernon and Fairfax County across the nineteenth century and today.) Visitors approached Mount Vernon from those routes and conveyances—and black people shaped their experience at Washington’s home, a critical part of my story. But those same African Americans employed the same roads (as well as byways known only to locals) and vehicles (as well as their own feet) to maintain links to nearby family and friends, conduct Mount Vernon’s daily business, or get into town for holiday shopping or church.

In short, what had begun as a project in cultural history took a clear turn toward social history.

That turn, I now think, was the key to telling a different kind of story. It’s an alternative history of American historic preservation, in which the leading characters aren’t elite white women, although they are still essential. It’s the local story of a national place: Mount Vernon in the neighborhood, not just in the national imagination. It’s the African American laboring history of a seemingly very white, elite site: Mount Vernon from the bottom up. And perhaps above all, it’s the nineteenth-century story of a supposedly eighteenth-century place—a story about life going on there long after the apparent lead character, the Father of his Country, was laid to rest—told from the perspective of a twenty-first-century historian intent on conveying that story from multiple points of view.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.2 (January, 2009).

Scott Casper, professor of history at the University of Nevada, Reno, and (for 2008-2009) visiting editor of the William and Mary Quarterly, studies and teaches nineteenth-century U.S. history, American cultural history, and the history of the book. With Jeffrey D. Groves, Stephen W. Nissenbaum, and Michael Winship, he edited A History of the Book in America: Volume 3: The Industrial Book, 1840-1880 (2007). His first book, Constructing American Lives (1999), looked at biography and culture in nineteenth-century America. He has taught in K-12 teacher institutes across the United States, including Mount Vernon’s residential summer institutes since 2000, and edits the Journal of American History’s annual “Textbooks and Teaching” section.