Last spring, the campus I have called home for the last twenty years suffered an unprecedented act of violence. A young man, caught in the grips of psychosis and beset by hateful delusional beliefs, decided to take vengeance on an entire college-town community. On May 23, he first stabbed to death his three roommates; then he got in his car and drove around the center of Isla Vista, California, attempting to gain entry to the Alpha Phi sorority house; shooting at passersby; and intentionally ramming at least four people with his car. Within about a quarter of an hour, three more lay dead, shot in cold blood, and fourteen were injured. As sheriff’s deputies rushed his car, he shot himself in the head. In the end, six young people died, all students at my university, along with the shooter, a student at the local community college. This story became national news—yet one more in the string of campus shootings that have descended like a plague on a nation whose patchwork mental health systems and variable gun control policies have failed to contain the present epidemic of violence.

But I also mused on the ways that we historians seem to specialize in speaking with the dead. We imagine the lives of those who have come before us, and we try, through discipline and deep immersion in the documents of a past world, to understand and reanimate the lives of those long dead.

Some 22,000 people—faculty, staff, and students—attended the memorial service for the victims. On the night before the service, one of the victim’s parents met his murdered child in a dream, an experience reported in a statement at the memorial:

I saw my son in a dream last night. And he asked me to give you this message. ‘My time at UCSB was the happiest two years of my life. I love all my friends who stayed with me through good and bad. I wanted to stay here forever with everyone. I know that there is still great injustice in the world and policies that can be improved. I cannot help with this any more, but you can. Please love and appreciate everyone around you.’

Watching from the stands, I felt for the pain of these families then, and I feel for them, and everyone affected by these horrific events, now as well. Even just a few short months later, our lives go on, strangely, much as before. The sidewalk memorials that emerged in the aftermath have been taken down and most students are back at school, though a few of the most heavily affected may never be able to return. Our community has pulled together in the wake of this disastrous loss, trying to ensure that some positive transformations come from this disaster.

The events of May 23, 2014, occurred just at the end of our spring quarter, and for me, that meant I was just at the end of a ten-week course in history and comparative literature called “Dreaming in Historical and Cross Cultural Perspective.” As my students filed back into the classroom on Thursday, two days after the memorial service and not even a full week since the horrific murders, we sat down together, not quite sure how to proceed, some 28 of us, all caught in different aspects of grief, all traumatized, to a greater or lesser degree, by the violence at our very doorstep.

Tentatively, I began the class. I had already scrapped my entire lesson plan for the day. Professors and teaching assistants had been carefully briefed by our campus mental health team, and we had been urged to focus on acknowledging students’ feelings, needs and reactions, and then to emphasize the need to keep going, to finish the quarter as we were able, and to give ourselves and each other permission to approach these events in a variety of different ways, without judgment.

The class focuses on several carefully controlled case studies in the uses of dreams and dreaming—from the Freudian revolution to modern clinical psychology, from sleep researchers and neuroscientists to religious practitioners and lucid dreaming advocates, as well as historians and anthropologists. We read a variety of historical and cross-cultural texts, emphasizing the unique meanings of dreams in different societies, and emphasizing the importance of understanding historical context and following established ethnographic methodologies through which to situate dream reports and dream practices. We had already looked at dreaming in the ancient Mediterranean, cruised through medieval and early modern Europe, and ended up with the Romantics. We had also read several articles and books that explored non-Western dream belief and dream practice in depth, which I assigned to open students’ minds to some of the insights of ethnographers about dreams and dreaming cross-culturally. We had just finished a book by a sociologist on the human potential movement of the 1960s and its appropriation of tribal dream beliefs and practices from the Senoi of Malaysia. I was about to give a lecture on lucid dreaming and, for want of a better word, New Age dream practitioners. But then the shootings happened. And after spending a weekend bombarded by pictures of the mentally ill perpetrator taken from his YouTube videos, I had no intention of subjecting my class to any of the Internet videos that were a fundamental part of my lecture.

Instead, I began the class by welcoming them back and reassuring them that, although it was hard, we would move forward together as best as we could. I paused, and asked how they were doing. We noticed that the memorial service had been a very special event, a time when the entire campus came together—something that I had never previously experienced in my twenty years on the faculty. And then I noted aloud how curious it was that a dream visitation—something that we had studied in our class—had been invoked at the memorial service. I invited them to share their thoughts about it with a short piece of free writing. Neither the significance nor the emotional power of this dream-event-become-dream-narrative was lost on my students. Clearly the dream visitation had offered a message of connection, a sense of purpose, and also some comfort—not only for the bereaved parents, but for all of us as well. Modern clinical theory would tell us that such dream cognition offers an important way of integrating challenging emotions, processing change, or signaling emotional growth, and that such dream visitations are frequently part of mourning.

Slowly, we worked our way through the mechanics of changed deadlines and altered assignments, figuring out how we would manage to finish up the quarter, so suddenly made trivial by the shocking intrusion of violent death into our everyday lives.

For my part, these sad events caused me to look more deeply at sources I had worked with in a book just completed, about the experiences and practices of dreaming in colonial New England. Did such dream visitations serve similar purposes for men and women of this far-away world as well?

Historic dream reports offer some of the most gripping sources I have ever encountered in my work as a historian. Men and women in early modern English and English colonial society commonly experienced dream visitations from deceased family members or friends. But while these dream reports seem so fresh, so recognizable, so universal, the methodological challenge of working with dreams cross-culturally (as I had taught my class) lies in always uncovering the particular contexts and the uniquely historical aspects of recorded dream phenomena. This essay, then, offers us a chance to explore the freshness and vitality—as well as the peculiarity—of dreams and dreaming in early modern English society.

The ubiquitous Boston magistrate, Samuel Sewall, frequently recorded stirring encounters in his dreams—though he did not always see fit to note who was dead and who was alive, leaving it up to the historian to discover that his nighttime visits were as often with the dead as with the living. Thus, for example, in December of 1688, while on board ship headed for England, and just after hearing from a passing ship of the Glorious Revolution staged by William of Orange, Sewall had this dream: “Last night I dreamed of military matters, Arms and Captains, and, of a sudden, Major Gookin, very well clad from head to foot, and of a very fresh lively countenance—his Coat and Breeches of blood-red silk, beckoned me out of the room where I was[,] to speak to me[;] I think ’twas the Town-house.” Following the dream, Sewall sat down to read “the Eleventh of the Hebrews,” a text on faith, and then sang the 46th Psalm, which is on God as a refuge and source of strength—acts, perhaps, to contain and to channel the dream’s power, and reclaim the dream for divine, rather than deluding, purposes. The dream itself was something of an invitation to Sewall, who was heading to England as an agent of the colony and hoping “to uphold the interests of the colony, now without a charter or a settled government, and to secure, if possible, a restoration of its privileges.” Daniel Gookin himself had, at his death in 1687, been known as a vigorous defender of Massachusetts’ liberties.

Sewall also made a remark in this dream report that reveals how particularly special dreams might sometimes circulate as stories, especially when they involved visitations from the dead. When he awakened from his conversation with Gookin, Sewall wrote, “I thought of Mr. Oakes’s Dream about Mr. Shepard and Mitchell beckoning him up the Garret Stairs in Harvard College.” Urian Oakes had succeeded Jonathan Mitchell as pastor of the church at Cambridge in 1671 (Mitchell had earlier succeeded Shepard). It appears that Oakes had received in his dream an invitation from these deceased predecessors, something remarkable enough that it was told, and retold, and here remembered by Sewall many years later. From this vantage point, Gookin’s lively appearance could also appear to be divine authorization of Sewall to take on the tasks assigned to him as colonial agent.

Such dreams of masculine hierarchy and paternal succession were not unfamiliar to Sewall, who frequently dreamed about his father-in-law, John Hull, or about other notable father figures, such as Charles Chauncy, the president of Harvard during Sewall’s years as a student. In 1695, Sewall had a disturbing dream that “Mr. Edward Oakes, the Father [of Urian Oakes], was chosen Pastor of Cambridge Church. Mr. Adams [an age-mate who had died in 1685] and I had discourse about the Oddness of the matter, that the father should succeed his Son so long after the Son’s death [Urian Oakes had died in 1681].” On awakening, Sewall noted, “Thus I was conversing among the dead.”

What did early modern men and women think of these occasions in which they spoke with the dead? If we follow the work of anthropologist Barbara Tedlock, whose prominent anthology on dreaming in the ethnographic literature stresses the critical importance of collecting not only dream texts, but also dream beliefs, practices of dream sharing, and indigenous interpretive techniques, we must try to locate such dream encounters in the local contexts in which the dreamers are embedded. And dreams and dreaming were at the crux of religious controversy in the seventeenth century. By well-established reputation, puritans were not supposed to place much store in dreams—certainly not more than in the revealed word of God in Scripture. But as is well known, by mid-century “hot Protestants” (radical reformers) of all sorts had begun to experiment with direct revelation. Quakers were using their dreams as a guide to their missionary preaching, leading them into trouble with puritans in Massachusetts Bay and elsewhere. Moderate puritan Philip Goodwin, in his 1658 Mystery of Dreams, attempted to recuperate dreams and dreaming as deserving of attention from even the most cautious believers. Work like Goodwin’s, though, reveals the place of dreams within a fairly well-established World of Wonders of which Europeans—Protestants as well as Catholics, and “hot Protestant” reformers as well as the mainstream orthodox—all took note.

Some early moderns believed that their dreams could be predictive of death. By far the most moving example of this sort is found in the work of Gervase Holles, a supporter of the crown during the English Civil War. In 1635, Holles had a vivid predictive dream that he recalled years later with as much clarity as if it had just occurred: “I dreamt my wife was brought to bed of a daughter and that shee and the childe were both dead.” Holles, still dreaming, and “(in a great deale of affliction)” suddenly found himself walking alongside a stone wall near his childhood home. He was “under the north wall of the close in the Friers Minorites at Grimesby (the place where I was borne) [and] my owne mother [Elizabeth Kingston, long deceased] walked on the other side hir hand continually touching mine on the top of the wall; and so (my heart beating violently within me) I awakened.”

Holles concealed this dream from his pregnant wife, Dorothy Kirketon, and yet “the day after made it too true in every sillable. For the Sunday morning following shee was delivered of a daughter, and both were dead within a hower after.” In addition to the dream’s obvious prediction of Dorothy’s death, Holles was also struck by many strange “parallel[s]” between the death of his wife and the death of his mother: “my mother brought my father 3 children as [Dorothy] did unto me; my mother died in childebed of a daughter as [Dorothy] did; the daughter [i.e .his daughter] died likewise as [had his sister]; and my sonne was within about six weekes as olde as I was at the departure of my mother.” Clearly he saw an ominous repetition of events in adulthood that had already happened to him in childhood. Indeed, the dream itself (as dreams so often do) had doubled the past loss before the future one had occurred, thus preparing Holles for the inevitable possibility of his wife’s death in childbirth. And while the dream brought him a taste of that powerful, painful separation, it also partially transformed it by the startling visit with his dead mother, their hands touching “continually” despite the gulf of years that separated them. From this he awakened in an intense emotional state: “(my heart beating violently within me)”.

Holles thought that such predictive dreams could sometimes occur as the result of a strong sympathetic resonance between two people. Elsewhere in his autobiography, he told the story of another dream—this one about the death of his son. In this night-vision, “one came to me and tolde me my son was dead; after which I wakened with a great passion and palpitation of my heart.” Finding that he could not rest again, he immediately arose and wrote to his (second) wife, Elizabeth, to ascertain whether his son was all right.

While Holles would be relieved at the answer—the boy was hale and unhurt—he thought the dream brought news nevertheless, because it had occurred on the very night after the battle of Newark (1644), when his cousin, William Holles, just a boy of 23, had, in fact, been slain. The elder Holles wrote of this event, “which though it proved not my dreame exactly true, yet relatively it did, I having ever placed him both in my affections and intentions in gradu filii.” Holles went on to allow as how, sometimes “amongst the variety of dreames,” there may be mere coincidences—”sometimes they may casually sort with the present accidents.” But, he noted, “(notwithstanding Hobs his new and atheisticall philosophy),” that “when there is between two an harmony in their affections, there is likewise betweene their soules an acquaintance and sometimes an intelligence.” It was this intelligence, in Holles’s view, that had allowed him to predict his wife’s death; the same special insight had caused him to dream of the death of his son, and when that was proven incorrect, nevertheless, the dream’s insight was proven on learning of the death of his nephew, who was like a son to him. Holles thought puritans were, well, too puritanical, at least when it came to dreams. He reported that his first wife’s parents had begged him to tell them about the dream that troubled him just before her death, but when he did, “they being rigid puritanes, made sleight of it.”

Despite this bad press, the puritans of New England actually seem to have treated dreams with much the same wonder and caution as Holles. A dreaming John Winthrop came into his chamber and saw there his wife and children, “in bed & 3: or 4: of hir Children lyinge by her with moste sweet & smylinge co[u]ntenances, with Crownes upon their heads & blue ribandes about their necks.” On awakening, Margaret and John talked over the dream, trying to determine if this celestial vision in fact meant that Mistress Winthrop and her children were among God’s elect. Other dreams, of course, were considerably grimmer. As the criminal court in Rhode Island learned in 1671, the murdered shade of Rebecca Cornell visited her sleeping brother, John Briggs, in fulfillment of a time-honored tradition through which victims of untimely deaths might reveal the presence of foul play by their apparition to relatives or other close friends. In this case, suspicion fell on Cornell’s son, Thomas, as the guilty party. Puritan or no, the English colonists of New England, like other early modern English men and women, developed a robust interchange with the afterlife, visiting and being visited by those who had already crossed over into the invisible world, a world accessed at night and while asleep.

Belief in the potential power of dreams colored colonists’ understanding of the dream beliefs and practices of their Algonquian neighbors. While we know that much was forever lost in the translation from indigenous to colonial understandings, colonial observers nevertheless were interested in natives’ dreams, even though they usually dismissed the Indians as “credulous” dreamers. Samuel de Champlain complained that the Montagnais he met in 1608 went in “such constant dread of their enemies, that they often took fright at night in their dreams, and would send their wives and children to our fort.” Champlain’s admonition, “that they should not take dreams as truth upon which to rely, since most of them are only fables,” may have mirrored orthodox European teachings of the day, but were clearly contradicted by the hopeful reliance on dreamed knowledge displayed by many later colonists. John Eliot’s first sermons among the Indians of Massachusetts were followed by questions such as: “In wicked dreames doth the soul sin?” and “doth God make bad men dream good Dreames?” And the Indian lives (and deaths) recounted by Experience Mayhew in the second decade of the eighteenth century seem no less marked by dream experience than those described by earlier authors. Indian dreams even sometimes rose to the level of prophecy: Jedidah Hannit, the daughter of the Martha’s Vineyard Indian minister Japheth Hannit, dreamt in her last illness that “there was a very dark and dismal time shortly coming on the Indian Nation; with which Dream being much distressed, she waked out of her Sleep, and had such an Impression on her Mind that what she had so dreamed would come to pass, and of the Dreadfulness of the thing so apprehended, that she immediately prayed earnestly to God, that she might not live to see the thing feared, but that she might be removed out of the World before it came to pass,” and thus, in just a few days, she died.

Her death made a convenient story for missionaries and colonists alike, convinced as they were that the Indians would soon be gone from Massachusetts’ shores. But both her prophecy and the seriousness with which Indian Christians took such dreamed knowledge suggest the continuing importance of dreams to these communities. The seriousness with which missionaries listened and recorded these dreams suggests that they, too, understood that powerful messages could sometimes appear in a dream, and, in addition, that sometimes a conversation about dreaming could contain both conquest and resistance. And in some cases, seventeenth-century New England had even seen native resistance movements centered around particular visionaries and their powerful dreams.

We had only three class sessions in which to absorb the impact of the shootings and to wrestle with the many narratives, including the powerful dream narrative, that emerged from that tragedy. We sought together for a path through the pain and the shock. For some students, that path seemed to come fairly quickly, allowing them to settle, at least for the time being, into a new normal that let them finish their work for the term. For others—those who had known the victims or who had lived in the apartment building where the murders began—the end of the quarter brought little resolution.

As for me, I spent the next weeks and months as others did, mourning the lost and engaged with the living in advocating for policy changes that might have saved lives. But I also mused on the ways that we historians seem to specialize in speaking with the dead. We imagine the lives of those who have come before us, and we try, through discipline and deep immersion in the documents of a past world, to understand and reanimate the lives of those long dead. Over the course of the summer I found myself reflecting on the ways that dreams help to potentiate new experience; calm emotional turmoil; and prepare us for loss. And I also reflected on the ways in which mine was a peculiarly modern means of interpreting such dream visitations. Early modern men and women knew death intimately, and in their world, the door was never closed between the world of the dead and that of the living. Dreams remained a conduit for them between these realms, albeit a door that was only meant to open when God gave it a push.

For us, the doorways dividing the dead from the living take more work to open. I am collaborating these days with a small group of students and library staff on an ongoing project to create an archival collection related to the Isla Vista murders. We hope that in retaining for future study some of the many objects, cards, letters, prayers, and other items left at the places where victims fell, these events will not be forgotten. Of course, my students and I hope, along with those bereaved parents, that those who lost their lives will still have the power to inspire action in others—to change the policies that need changing, and to build a community that honors their spirit.

Sometimes, just every once in a while, I myself have a particular dream of the dead. Usually I am in a diner, talking with a group of friends. I look over my shoulder, and I see my godmother, gone more than twenty years now, sitting in a booth just a bit away. This is the person, more than anyone else, who supported my love of history when I was a child, spending countless hours taking me to historical sites and museums. I try to extricate myself from the party, offering excuses, but I am trapped in an inside seat and no one hears me. Finally, in exasperation, I blurt out, “I’m sorry that I have to go, but I want to go sit with my godmother. She’s been dead for a long time, and I don’t get to talk with her that often.” By the time I finally get free, she slips away, just out of reach, until the next time. And so I, like the rest of us moderns, have to find other ways to speak with the dead.

Further reading:

The dream reported by James Cheng Yuan Hong’s family was contained in the remarks of Richard Martinez, another parent, who was designated as spokesman for the victims’ families at the memorial service on May 27, 2014, at Harder Stadium, University of California, Santa Barbara.

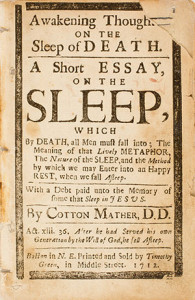

The dreams mentioned are found in a variety of sources, all cited in full in Ann Marie Plane, Dreams and the Invisible World in Colonial New England: Indians, Colonists and the Seventeenth Century (Philadelphia, 2014).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.2 (Winter, 2015).

Ann Marie Plane is professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and training and supervising analyst at the Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis in Los Angeles, California.