I can still recall perfectly the day Johanna Ortner walked into my office, asking me to be her doctoral advisor, and in search of a dissertation topic. I told her that someone ought to write a historical biography of the relatively forgotten abolitionist-feminist, writer, poet, and temperance advocate, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Having already expressed her interest in black women’s history to me, Johanna was up to the challenge. With a historian’s passion for archival research, she made a brilliant discovery: she found Harper’s first book of poems, Forest Leaves, thought until now to be lost to history. My interest in Harper stemmed from the book I was writing, now complete, which centers on African Americans, free and enslaved, in the history of the abolition movement. In my research, I came across a host of black writers, mostly ignored by historians, but whose work had been carefully recovered by literary scholars such as Henry Louis Gates Jr., Vincent Carretta, Jean Fagan Yellin, Robert Levine, Joanna Brooks, William Farrison, and most recently, Ezra Greenspan, to name a few.

Black women writers, as Gates argues in his essay, “In Her Own Write,” have been central to the genesis and development of African American literature, starting with Phillis Wheatley. We are still in the process, he goes on to note and as Johanna’s discovery makes clear, of “unearthing the nineteenth century roots” of black women’s literary tradition. Harper, the “bronze muse of the abolitionist movement” in the apt words of her biographer, Melba J. Boyd, is one of them. With her too, I turned to the work of literary scholars like Boyd, Carla Peterson, Frances Smith Foster, and Maryemma Graham to fully appreciate the breadth of Harper’s oeuvre, poems, short stories, novels, and not the least, her speeches, many of which went unrecorded in the abolitionist and black presses. After the Civil War, her speeches were neglected in the temperance and women’s rights press. Indeed, it was Harper’s skills as an orator and activist that has led Peterson to include her in a group of black women “doers of the word” and Graham to call her a “supremely oral poet.” I suspect that we have yet to recover the full range of Harper’s writings and words.

My own interest in Harper was piqued not so much by her now well-established authorial reputation in African American letters but by her work as a forgotten activist and polemicist for abolition, women’s rights, and black citizenship. My encounter with her began in the pages of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which contained accounts of her accomplished and persuasive antislavery speeches in the 1850s. According to an admiring John Stephenson, on one occasion, Harper spoke “eloquently of the wrong of the slave” for two hours “in a soul stirring speech.” He reported to Garrison, who knew Harper’s abolitionist uncle William Watkins well, that “Miss Watkins is a young lady of color, of fine attainments, of superior education, and an impressive speaker, leaving an impression, wherever she goes, which will not soon be forgotten.” (Garrison, along with the Quaker abolitionist Benjamin Lundy, had lived with black abolitionists Jacob T. Greener and Watkins in a boarding house in Baltimore, when he briefly co-edited The Genius of Universal Emancipation with Lundy in 1829.)

On the eve of the Civil War and her short-lived marriage to Fenton Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins (fig. 1) was a well-established presence in the abolitionist lecture circuit. She was hired as a lecturing agent by the Maine Anti Slavery Society, went on lecture tours as far west as Michigan, according to the black abolitionist William C. Nell, and assisted the adroit secretary of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, William Still. As she wrote succinctly to Still, her first biographer, who recalled how generously she had contributed to the abolitionist underground: “My lectures have met with success.” She added proudly, “I took breakfast with the then Governor of Maine.”

As an abolitionist lecturer, Harper honed to perfection a polemical political style that appears to differ with the seemingly sentimental and religious form of Forest Leaves. In her lectures, she pointedly contrasted the reality of black suffering with popular antislavery fiction: “Oh, if Mrs. Stowe has clothed American slavery with the graceful garb of fiction, Solomon Northrup comes up from the dark habitation of Southern cruelty where slavery fattens and feasts on human blood with such mournful revelations that one might almost wish for the sake of humanity that the tales of horror that he reveals were not so.” Harper powerfully makes clear that Northup’s unvarnished story of the harsh labor regimen and commodification of black bodies in the Cotton Kingdom is a truer depiction of slavery than Stowe’s best-selling novel saturated with the tropes of romantic racialism. As an ardent advocate of the Quaker-led free produce movement, Harper argued that she would rather pay for a coarse dress and “thank God that upon its warp and woof I see no stain of blood and tears; that to procure a little finer muslin for my limbs no crushed and broken heart went out in sighs, and that from the field where it was raised went up no wild and startling cry unto the throne of God to witness there in language deep and strong, that in demanding that cotton I was nerving oppression’s hand for deed of guilt and crime.” Cotton, as Harper realized, was the fabric of slavery. Her lecture combined literary sentimentalism with an acute perception of the political economy of slave labor-grown cotton.

Harper’s abolitionist imaginary of bloodied bodies and soul-crushing oppression presents an obvious contrast to the lovely imagery of the poems in Forest Leaves. But even in this initial literary endeavor, Harper deploys abolitionist rhetoric. In her first poem, “Ethiopia,” she writes,

Yes, Ethiopia, yet shall stretch

Her bleeding hands abroad,

Her cry of agony shall reach

The burning throne of God

Based on an oft-quoted Biblical saying deployed by early black abolitionists, Harper repeats this first paragraph at the end of her poem with added emphasis, “Oh stretch” and the conviction that Ethiopia shall “find redress from God.” Black abolitionists from Richard Allen to David Walker often evoked divine vengeance against the crimes of slavery and racism. William Watkins, who had brought up his orphaned niece and was a teacher and clergyman himself, no doubt provided her with a political education in abolition as well as a conventional education in reading and arithmetic.

Harper’s lectures combined abolitionist polemics with literary romanticism, the hallmark of her popular poems like “The Slave Mother.” Some of her poems from Forest Leaves, for instance the “Bible Defence of Slavery,” encapsulated the abolitionist critique of proslavery theology and Biblical literalism. Perhaps her most overtly political poem was the one that she sent to Senator Charles Sumner in 1860 praising his abolitionist speech, “The Barbarism of Slavery.” That caught my attention. While writing an article on the caning of Sumner, I discovered that African Americans corresponded frequently with the Radical Republican from Massachusetts and most, like Frederick Douglass, anointed him “our Senator.” But it was Harper’s poetic tribute to Sumner that remained with me. Harper’s poetry eloquently captured black sentiment, demonstrating the political power of her art. Like another black woman abolitionist, Charlotte Forten, Harper idolized Sumner. But she was one of the few African American women to directly engage him and the politics of slavery and antislavery.

Thank God that thou hast spoken

Words earnest, true, and brave;

The lightning of thy lips has smote

The fetters of the slave.

……………………….

Thy words were not soft echoes

Thy tones no siren song;

They fell as battle-axes

Upon our giant wrong.

Clearly, in a nineteenth-century literary style, Harper, as Graham argues, like writers associated with the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, rejected the conceit of art for art’s sake. For her as for many African American authors, the art of writing was a profoundly political act.

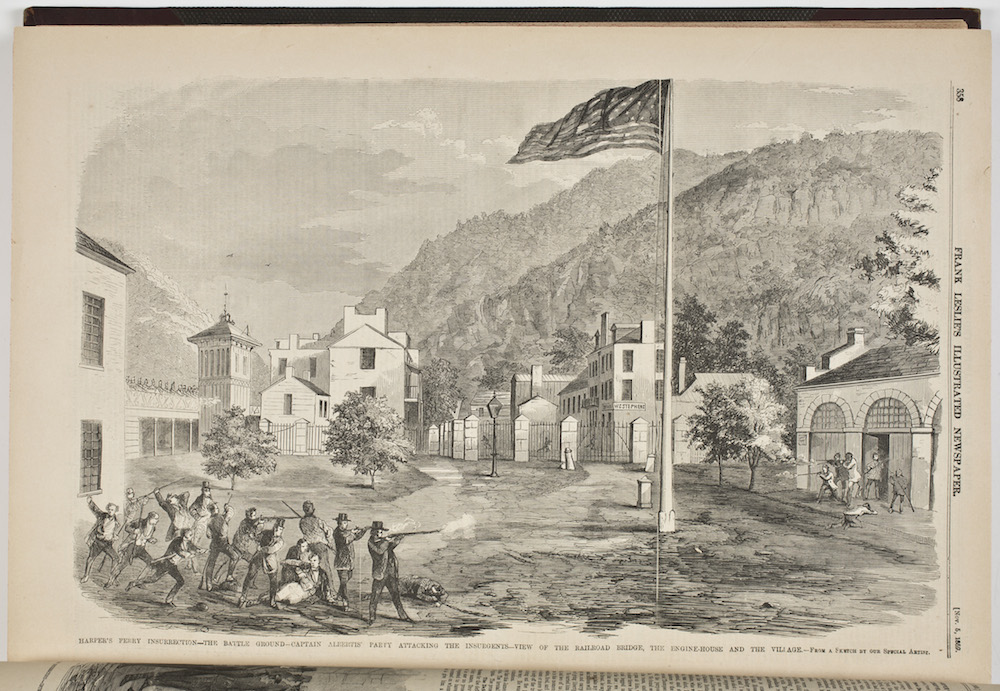

My third encounter with Harper, the polemicist, came through an essay that she wrote for the only black newspaper that was published continuously during the Civil War, the Christian Recorder. While researching an article on Abraham Lincoln and black abolitionists, I found a treasure trove of essays, letters, and editorials written by African Americans on the war, the president, emancipation, and black citizenship here. Eric Gardner’s recent work with this newspaper resulted in his discovery of a chapter of Harper’s novel Sowing and Reaping, and the later—and until now, unknown—writings of black abolitionist-feminist Maria Stewart. Such remarkable finds highlight the Christian Recorder’s significance as a source of early African American literature. Yet Harper’s article on colonization in the Recorder has escaped the attention of scholars and is not included in Foster’s 1990 collection of her poems, fiction, speeches, and letters. I discovered this essay published in the Christian Recorder on September 27, 1862 (fig. 2) under the title “Mrs. Francis E. Watkins Harper on the War and the President’s Colonization Scheme.” Harper’s essay opens with a radical abolitionist condemnation of the nation at the high tide of Civil War nationalism:

I can read the fate of this republic by the lurid light that gleams around the tombs of buried nations, where the footprints of decay have lingered for centuries, I see no palliation of her guilt that justifies the idea that the great and dreadful God will spare her in her crimes, when less favored nations have been dragged from their place of pride and power, and their dominion swept away like mists before the rising sun. Heavy is the guilt that hangs upon the neck of this nation, and where is the first sign of national repentance? The least signs of contrition for the wrongs of the Indian and the negro? As this nation has had glorious opportunities for standing as an example to the nations leading the van of the world’s progress, and inviting the groaning millions to a higher destiny; but instead of that she has dwarfed herself to slavery’s base and ignoble ends, and now, smitten of God and conquered by her crimes, she has become a mournful warning, a sad exemplification of the close connexion between national crimes and national judgments.

After penning this philippic, Harper issues a stinging critique of Abraham Lincoln’s wartime colonization schemes: “The President’s dabbling with colonization just now suggests to my mind the idea of a man almost dying with a loathsome cancer, and busying himself about having his hair trimmed according to the latest fashion.” The playfulness and skill of the mature Harper’s critique here stands in contrast to the earnest tone of her first literary production, Forest Leaves. Schooled by her uncle William Watkins’ anti-colonization articles in the abolitionist newspapers Freedom’s Journal and The Liberator, which he published under the nom-de-plume “A Colored Baltimorean,” Harper vigorously made the case for black citizenship anew. She advised,

Let the President be answered firmly and respectfully, not in the tones of supplication and entreaty, but of earnestness and decision, that while we admit the right of every man to choose his home, that we neither see the wisdom nor expediency of our self-exportation from a land which has been in large measure enriched by our toil for generations, till we have a birth-right on the soil, and the strongest claims on the nation for that justice and equity which has been withheld from us for ages—ages whose accumulated wrongs have dragged the present wars that overshadow our head.

She mocked the notion that the United States could part with “four millions of its laboring population.” Harper’s anti-colonization piece, unlike her later well-known speeches on women’s rights, has not received any sustained scholarly analysis. While Johanna’s recovery of Forest Leaves allows scholars of literature to further develop their criticism and understanding of Harper’s literary productions, as is evident in other essays in this issue, her activist speeches and writings, lying hidden in plain sight, help us reconstruct the nature of her forgotten activism. These two acts of recovery and discovery help us view Harper as somewhat of a renaissance woman, a woman of many parts and ideas.

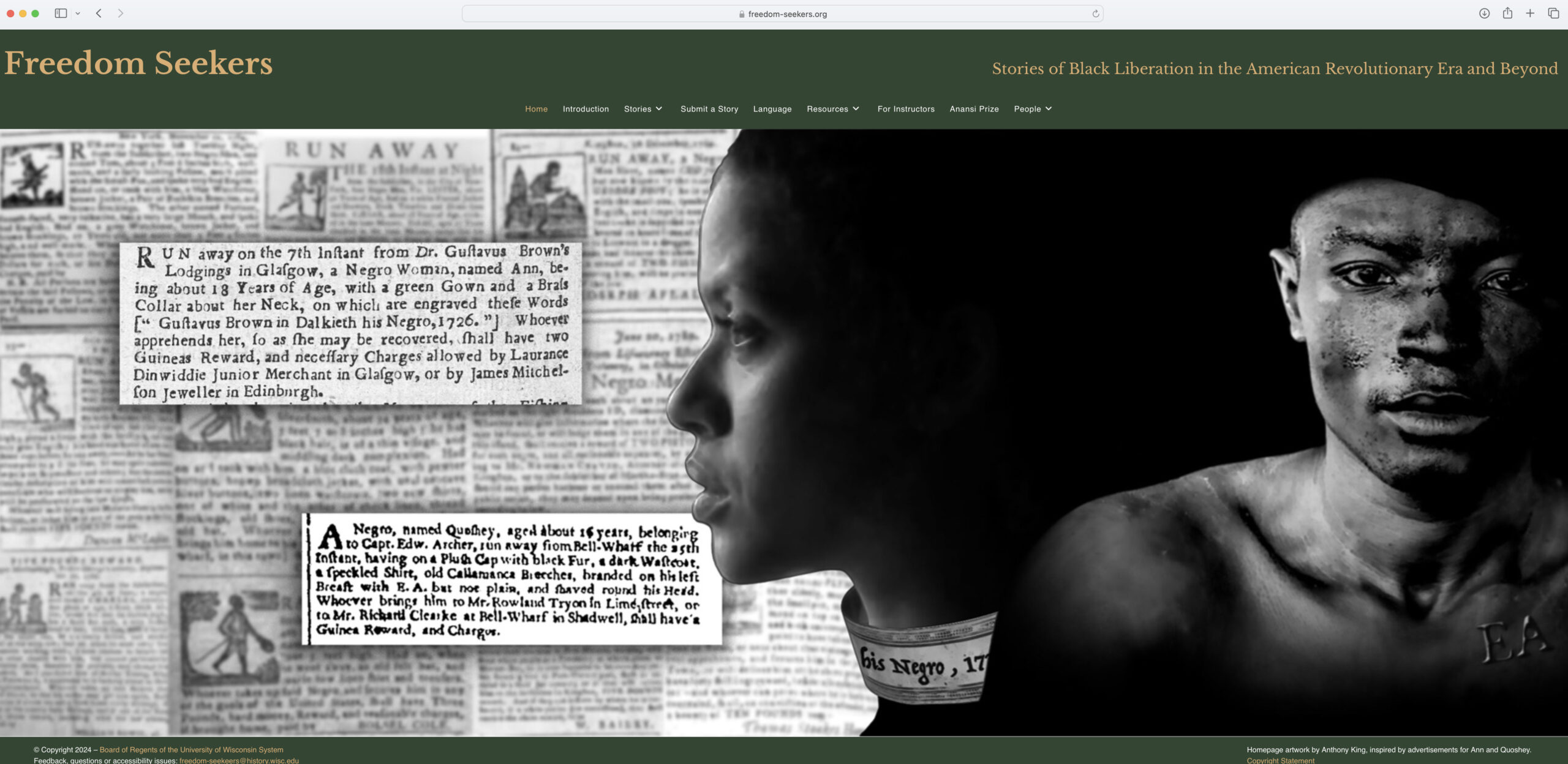

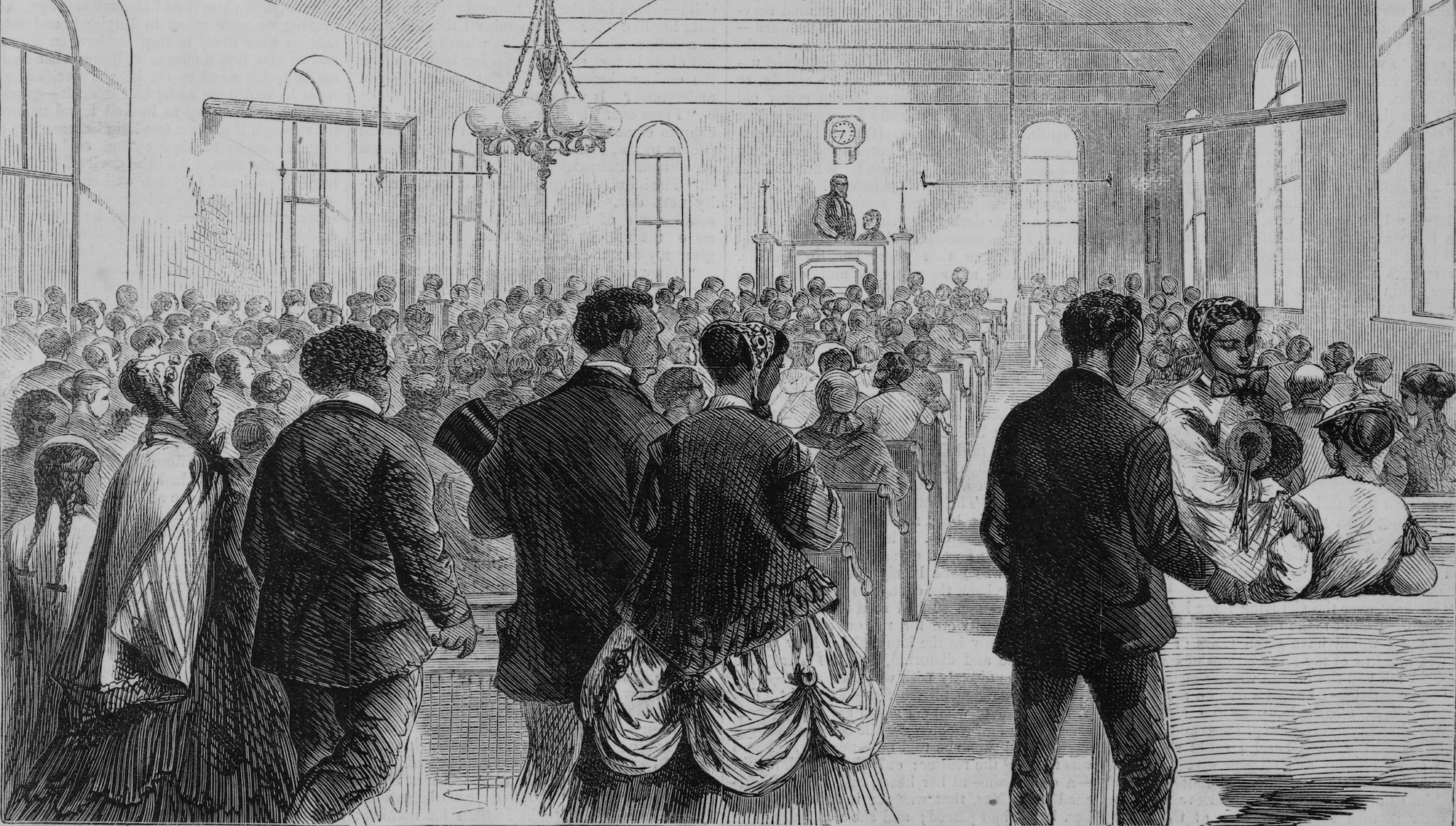

Recent historians of black women have recast Harper as a pioneering African American feminist. Her well-known speech during the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1866 has made her a black feminist icon, her work read as an early iteration of intersectional analyses of race and gender: “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.” Later in the speech, Harper drew attention to her own property-less and right-less state as a widow and famously critiqued white suffragists for ignoring the particular oppressions of African American women. “You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man’s hand against me.” Born from the abolitionist schism over “the woman question,” the nineteenth-century women’s rights movement met in national and state conventions in the 1850s and 1860s. Before the emergence of an independent suffrage movement, Garrisonian and women abolitionists like Harper participated in them regularly. (See the calls for the National Woman’s Rights Conventions of 1858 and 1866 illustrated here [figs. 3, 4].)

For the rest of her life, Harper continued to draw attention to the plight of the “Coloured Woman” and became a spokeswoman for Frances Willard’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which was closely allied with the women’s suffrage movement. Black women’s labor, Harper said in her speech to the Women’s Congress in 1878, along with their education, “energy and executive ability” entitled them to equality. Historically, black women, like most working class and immigrant women, had always worked outside the home, she reminded her audience:

In different departments of business, coloured women have not only been enabled to keep the wolf from the door, but also to acquire property, and in some cases the coloured woman is the mainstay of the family, and when work fails the men in large cities, the money which the wife can obtain from washing, ironing, and other services, often keeps pauperism at bay…They do double duty, a man’s share in the field, and a woman’s part at home.

In alluding to the “double duty” performed by working class black women, Harper anticipated the “second shift,” one of the pivotal metaphors of modern feminism.

Recent scholarship has given us a heretofore unknown archive of black women’s writings: Jean Fagan Yellin’s authentication of Harriet Jacobs’ narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, and Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s discoveries of Harriet Wilson’s Our Nig and Hannah Crafts’ The Bondwoman’s Narrative. Crafts has been identified as Hannah Bond, a fugitive slave from North Carolina, by the literary scholar Greg Hecimovich. Historians, philosophers, and political theorists have also sought to recover black women’s early intellectual history. If Harper has long occupied a pride of place in African American literature, she surely deserves a similar place in African American intellectual and political history. I have a hunch that many still undiscovered nuggets await Johanna Ortner in her quest to write a historical biography of by far one of the most interesting American women writers and activists of the nineteenth century.

Further Reading

On early African American women’s literature see the multi-volume The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers, Carla L. Peterson, “Doers of the Word”: African American Women Speakers and Writers, 1830-1880 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1995), and Frances Smith Foster, Written By Herself: Literary Production by African American Women, 1746-1892 (Bloomington, Ind., 1993). On Harper see Melba Boyd, Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E.W. Harper 1825-1911 (Detroit, Mich., 1994), Frances Smith Foster, A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (New York, 1990), and Maryemma Graham, Complete Poems of Frances E.W. Harper (New York, 1988). On the Christian Recorder see Eric Gardner, Black Print Unbound: The Christian Recorder, African American Literature, and Periodical Culture (New York, 2015). On my encounters with Harper see Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven, Conn., 2016), “Allies for Emancipation?: Lincoln and Black Abolitionists,” in Eric Foner ed., Our Lincoln: New Perspectives on Lincoln and His World (New York, 2008): 167-196, “The Caning of Charles Sumner: Slavery, Race and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War,” Journal of the Early Republic 23 (Summer 2003): 233-262. On black women’s intellectual history see Kristin Waters and Carol B. Conaway eds., Black Women’s Intellectual Traditions: Speaking Their Minds (Burlington, Vt., 2007) and Mia Bay et al eds., Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2015)

This article originally appeared in issue 16.2 (Winter, 2016).

Manisha Sinha is professor of Afro-American Studies and history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is the author of The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina (2000) and The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (2016).