What started out as just wanting to make a few paintings of whales ultimately became an eight-year project, with still no end in sight. Whaling—or, at least, the history of American whaling—does not give up her secrets easily. And looking for reference material about one aspect of whaling often leads to other bits of whaling lore you never knew existed.

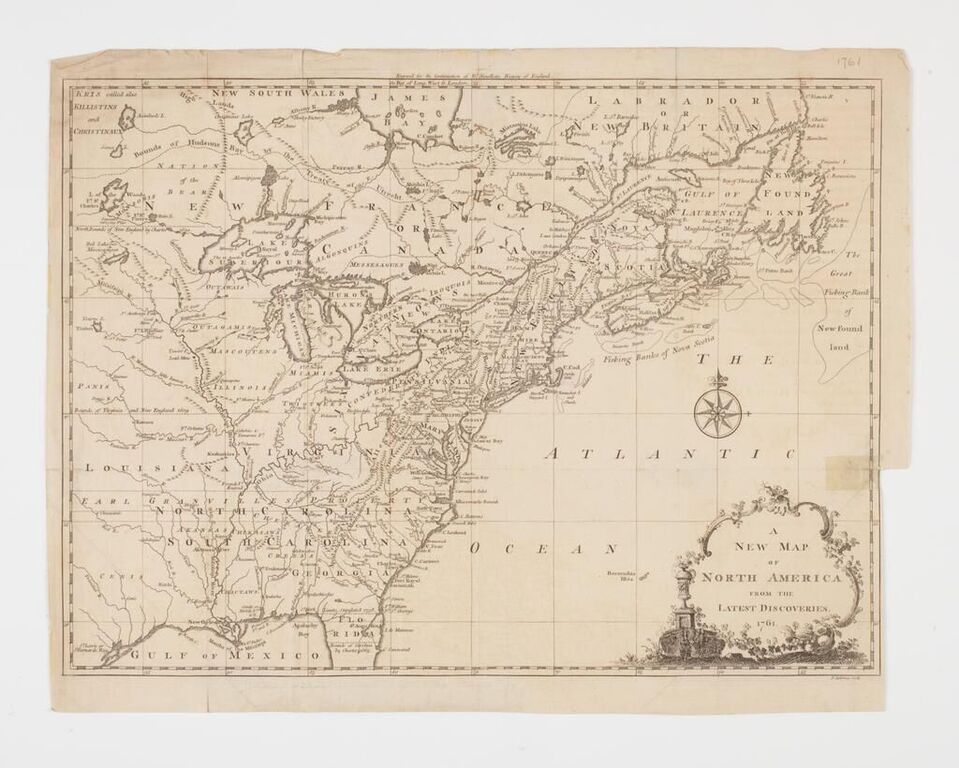

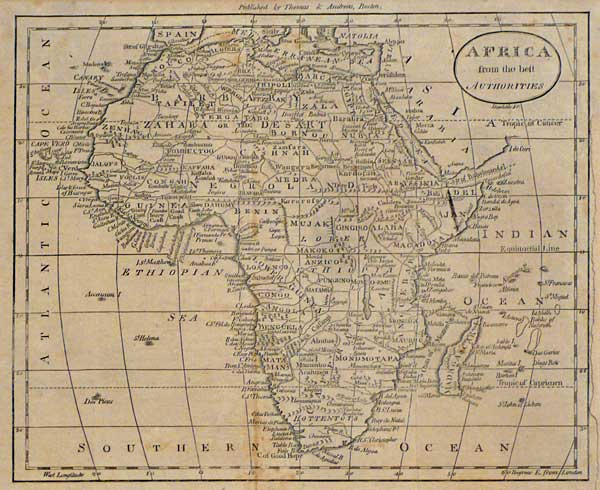

My way of thinking is circuitous to begin with, and easily waylaid. So, standing in the main entry hall of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, looking at a map that showed the global voyages of whalers over the course of several centuries, I was struck by how many boats had been lost at sea in the relentless pursuit of whales. Each of those boats had a crew of between twenty and fifty men, many of whom left behind wives, children, homes, and families.

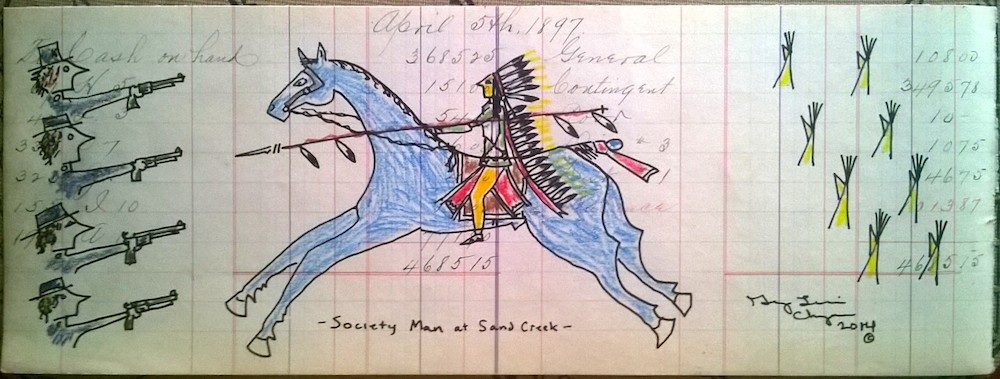

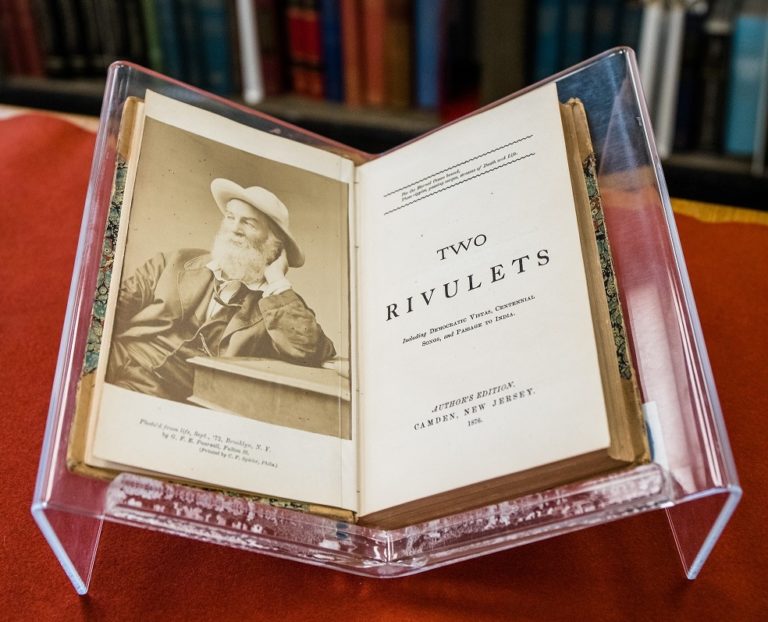

And then off in one corner, on display almost as an afterthought, I saw a whaling logbook, and everything changed.

It took some time, but eventually I discovered that the Providence Public Library has the second-largest collection of whaling logbooks in the world. I called them up, and they invited me down for a look. Upon arrival, they pointed me in the direction of two huge bookcases, and said something along the lines of “there you go!” So I started at the beginning, and worked my way to the end, my fingers black from turning the pages. It was as though some small part of whaling was rubbing off on me, the soot from the try pots, fires that burned night and day. Melville wrote that the smoke from those fires smelled “like the left wing of the day of judgement.” The true history of American whaling is in those logbooks, and hundreds like them, written by the men who went to sea. Those pages hold the excitement of the hunt, the chase, the danger, as well as the boredom and near-constant longing for home, all of it the sum parts of whaling. And many contained visual sketches, including studies of different whale plumes, which could be used from a distance to identify whales by type, and thus by value.

They put to sea, and hoped.

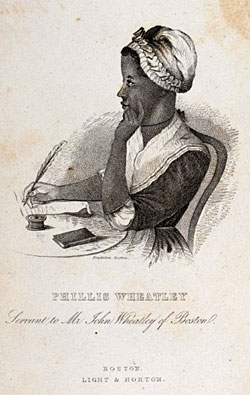

While trying to figure out what the hell I could do with the logbooks, I was painting portraits of some of the children I know on the island where we live, dressing them in period outfits and giving them harpoons or whale teeth or silhouette portraits to hold, tangible memories of their fathers, grandfathers, brothers and uncles. Text from the logbooks also began appearing on the canvas of these portraits, further heightening the sense of these remnant sea-borne inheritances. All those men lost at sea called themselves “The Children of Light,” because that was what they were doing: lighting the homes and streets of the new Republic with whale oil.

One day at the library, I noticed a couple of boxes on a shelf marked “scrimshaw.” Jordan, the librarian, pulled them down and opened them up. Each was packed with gray foam, and nestled into little cut-out pockets were scrimshawed teeth of sperm whales, dozens of them, carved over the long course of whaling voyages.

Of course, I had to do some scrimshaw now. Ivory, however, under which whale teeth fall, is outlawed in the United States. By chance, someone on the island needed their piano fixed, and I happened to spot a small truck with “Piano Repair” on the side while I was in line for the car ferry. I tapped on truck driver’s window.

“Excuse me, sir,” I began, “do you happen to have any old piano keys?” The man’s eyes lit up.

I found myself east of nowhere a few days later, in his “shop,” essentially a collapsing corner of a garage full of boxes and bags and old cans brimming with what might very well have been several thousand piano keys. The tails (the narrow part next to the black keys) were a dollar. The mains (the piece where the finger strikes) two dollars. “Cash Only,” of course. I went a little crazy at the ATM several miles down the road.

Wanting to make scrimshaw is one thing; figuring out how to do it is quite another. Did you know that almost nothing sticks to ivory? That, in fact, there is special Piano Key Glue available only from a company in Chicago? Did you also know that piano keys were originally bedded down with whiting, a kind of pasty nastiness that has to be soaked off, but not for too long, and then scraped away with a knife? Oh, the things I know about piano keys, and how much work it takes to make panels, prime panels, glue the keys, keep them straight, clamp them just so, then clean them up and trim the edges, fill the gaps, then—and only then—actually prepare to make a mark with a very expensive, very sharp, slightly lethal surgical needle, and hope it is a good mark, a mark that might eventually become a whale incised into dozens of small pieces of ivory.

That’s how my work gets made: in bits and pieces, one thing leading to another, then another, until the process stops. With the whales, this hasn’t happened yet. Part of me hopes it never will. The historical materials brought an undercurrent of American narrative to this series that deeply intrigues me. The logbooks, in particular, seeped, in many different ways, into all the work presented here. As you can see, I even began to replicate the form of the logbooks themselves, with studies of spouts and ocean colors.

I could never have been a whaler, but would love to have been aboard a whaleship in 1856, to see how it was done, meet those men, hear their stories, somehow get it all down in my own sketchbooks and journals, my fingers black from soot, as well as ink.

To have put to sea, and hoped.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.3.5 (Summer, 2017).

Scott Kelley studied at the Cooper Union School of Art, New York; the Slade School of Art, London; and was a fellow at the Glassell School of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Kelley’s work is in collections, including the Portland Museum of Art and the Portland Public Library. He has received numerous fellowships, including a grant from the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program, which sent him to Palmer Station, Antarctica. Scott Kelley lives and works on Peaks Island, Maine, with his wife, Gail, their son, Abbott, and their imaginary pig, Lunchbox.