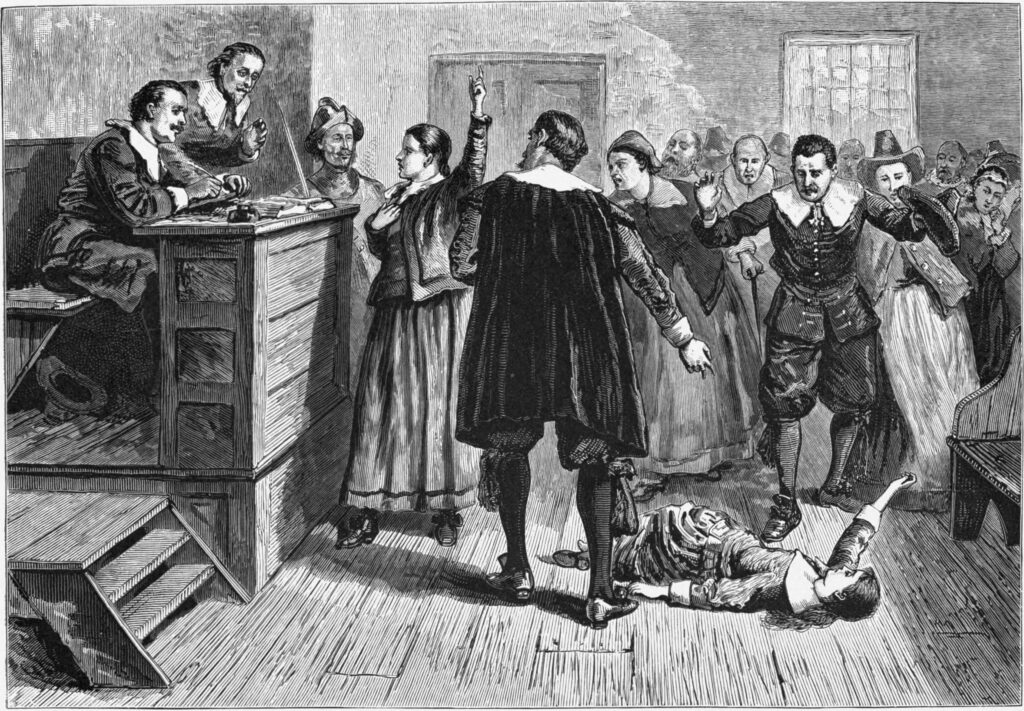

In a 1996 New Yorker article, Arthur Miller discussed the circumstances surrounding his writing of The Crucible forty years earlier. To create the central dramatic plot of the play, Miller raised the age of Salem Village accuser Abigail Williams from eleven years old to seventeen and placed her in the household of his hero John Proctor as a maidservant to his wife Elizabeth. When Miller read the record of Elizabeth’s court hearing of April 1692, he was intrigued by a passage that vividly described a moment when Abigail Williams was about to strike Elizabeth in court. When Abigail raised her fist and moved toward Elizabeth as though to hit her, she opened her fist, and her hand “came down exceeding lightly as it drew near to said Procter, and at length, with opened and extended fingers, touched Procter’s hood very lightly.” Immediately Abigail cried out about her fingers: “her fingers, her fingers, her fingers burned.” Miller explained his interpretation of Abigail’s gesture and her crying out in pain as the key to the play: “By this time [in writing the play], I was sure, John Proctor had bedded Abigail, who had to be dismissed [from the Proctor house] most likely in order to appease Elizabeth. There was bad blood between the two women now.” Miller then commented, “My own marriage of twelve years was teetering and I knew more than I wished to know about where the blame lay,” referring to his affair with Marilyn Monroe. Miller divorced his wife, Mary Slattery, in 1956 and married Monroe the same year. “Moving crabwise across the profusion of evidence,” Miller recalled, “I sensed that I had at last found something of myself in it, and a play began to accumulate around this man.” The Proctor of the play was inspired by Miller’s projection of himself into events of 1692 and it is worth digging a bit deeper into the family matters between John and Elizabeth.

Reflections on the Relation between History and Literature: The Crucible and John and Elizabeth Proctor of Salem

The Proctor of the play was inspired by Miller’s projection of himself into events of 1692 and it is worth digging a bit deeper into the family matters between John and Elizabeth.

Despite John’s dalliance in the play with Abigail Williams, John and Elizabeth, as Miller portrays them, are strong-minded individuals who still love and support one another. In one courtroom scene Elizabeth pleads with John to cast aside his pride and confess to witchcraft and thereby save himself from execution. The Salem court, Elizabeth sobs, is unjust and not worth dying for. Confession, they both know, will save his life, at least for a time. In 1692 individuals who confessed to acts of witchcraft were deemed to be harmless and were not regarded as a danger to the public. Indeed, in 1692 fifty-eight individuals offered confessions in which they named other suspects and only five confessors were convicted. None were executed.

In The Crucible, Elizabeth is ensnared when she is forced to testify about her knowledge of John’s affair with Abigail Williams. Elizabeth was aware of what had taken place, but she denies it in court out of her love for John and to save his good name, even though she had told Judge Danforth about it. Danforth quickly proclaims that Elizabeth had given false testimony and he upholds the charge of witchcraft against her. Elizabeth was caught in a lie, one of the court’s traps in 1692, to force self-incrimination and turn unwitting defendants into frightened confessors who were then required to name other suspects in order to save themselves, thus becoming accomplices of the court in ferreting out other suspected witches. This was the precise parallel that Miller saw between the efforts of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which grilled him about his acquaintances in the Communist Party, and the purpose of the Salem court.

In his close reading of some of the 1692 court records, Miller also picked up on an intriguing detail about the timing of Elizabeth’s pregnancy which kept her from the gallows. In the play, Elizabeth knows that she is pregnant well before she is arrested. In 1692 the witchcraft complaint against her is dated April 4, 1692. She was arrested seven days later on April 11 and examined by the Salem magistrates in court where John was also present. The next day both she and John were transferred to jail in Boston. Both were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death on August 5. John was sent to the gallows two weeks later on August 19, together with five others. But Elizabeth was not among them. Like John, she had refused to confess, but she had been granted a reprieve because she was pregnant. As the court did in such cases (there was one other in 1692), it agreed to postpone Elizabeth’s execution until after the birth of her child. Taking the life of an innocent unborn child was against the Puritan sense of God’s justice. The Salem court was closed at the end of October. In early February 1693, the newly established Superior Court was about to send Elizabeth to the gallows after she had given birth in jail in late January, but the governor stepped in and ordered her reprieved for a second time. She and her son remained in jail until May 1693, when she and the last of the remaining prisoners of the Salem debacle were freed.

In the play, Miller portrays the moment when John fully realizes the implications of Elizabeth’s pregnancy, that she will be spared the gallows until after the child is born. It is a poignant, almost silent scene in the last act, just before John is sent to the gallows, when he sees Elizabeth fully pregnant. They are alone, and their affection for each other transcends the traumatic circumstances of the moment. Miller gives the following stage instructions: “He reaches out his hand as though toward an embodiment not quite real, and as he touches her, a strange soft sound, half laughter, half amazement, comes from his throat. He pats her hand. She covers his hand with hers. And then, weak, he sits. Then she sits facing him.” Proctor: “The child?” Elizabeth: “It grows.” John then asks about their young sons, if they are safe, and she tells him they are well cared for. John replies, “You are a—marvel, Elizabeth.” She is pregnant, and he is amazed at her good fortune. His smile and comment that she is a “marvel” appear to suggest that he knows she will be reprieved and possibly escape the gallows altogether, which is what happened.

But was there more to it in 1692? Local Salem historian and genealogist Sidney Perley indicates that Elizabeth gave birth to a son on January 27, 1693. Knowing the date when Elizabeth gave birth and assuming a normal forty-week gestation period, it is possible to calculate the probable date of Elizabeth’s conception, which may indicate an untold story (see pregnancy wheel gestation calculator). Elizabeth was in her early forties. She had been married to John for seventeen years and had given birth to six children. Given a gestation period of forty weeks (April 22), conception would likely have taken place in late April or early May, when both were in the Boston jail where they had been transferred from the Salem jail on April 12, the day after Elizabeth’s hearing. Conception would have occurred before shackles were placed on the witchcraft suspects in late May to prevent them from afflicting their accusers. Conjugal relations in jail may seem unlikely to us today, but seventeenth-century colonial jails did not serve the same purpose as jails today. They were supervised locked houses where suspects were held for a short time before trial. John and Elizabeth might also have paid for a private room, which was possible in the Boston jail house, or as a married couple they may have been granted makeshift privacy. Given Elizabeth’s age and her previous six births, pediatricians consulted about this question say that a longer gestation period would have been highly unlikely. There was in fact a one-week period between Elizabeth’s accusation on April 4 and her incarceration in the Salem jail on 10 April, when she and John and might have attempted conception, but this would have involved an unlikely forty-two week gestation period before Elizabeth gave birth. Either way, however, Elizabeth’s conception while in jail or just before was likely attempted in hopes of a reprieve. Against all odds, they succeeded. John and Elizabeth managed to have Elizabeth become pregnant so that she could escape being hanged.

By August 19, John’s and Elizabeth’s execution date, Elizabeth would have been well over three months pregnant, and her condition would have been obvious to the court and to John. Even if they did not meet together in jail for the last time, as Miller portrays it, John would still have known that Elizabeth was temporarily reprieved because she was not in the ox cart that took him and four others from the Salem jail to Gallows Hill. Elizabeth’s execution was postponed by temporary reprieve until after she gave birth. Then the new governor stepped in and gave her a second reprieve, overruling Chief Magistrate William Stoughton’s demand that she be sent to the gallows in early February. The evidence suggests that despite the awful circumstances involved, John and Elizabeth tried to make it work out that way while in jail or just before. In either case her pregnancy was a “marvel” indeed.

Elizabeth named her newborn child John. Her husband had already fathered another son named John by his second wife, forty-one-year-old Elizabeth Thorndike who died in 1672. Unfortunately, the older John Jr. and his stepbrother Benjamin, by John’s first wife, would become a source of conflict for Elizabeth.

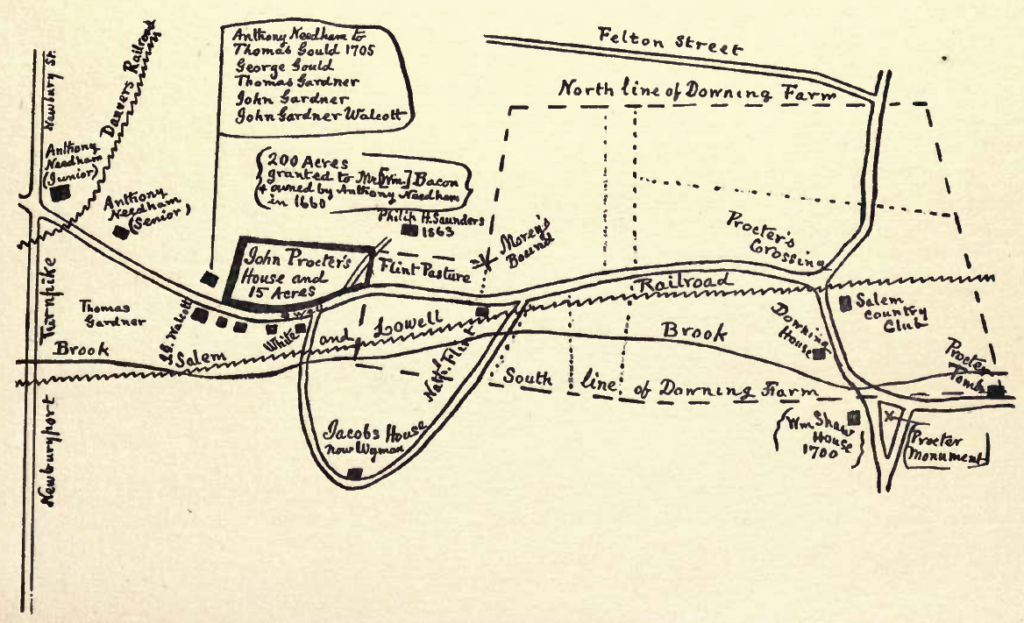

In February, 1674, John wrote out a will in anticipation of his marriage to Elizabeth whose family name was Bassett. He divided his Salem estate equally among all of his children, and gave his land in Chebacco, which was then part of Ipswich, to Elizabeth Bassett as a dower gift. Elizabeth and John were married in April of that year. Fourteen years later in January 1688, he wrote out a new will which gave Elizabeth a share in his Salem house and lands, about fifteen acres, together with his sons and their families. This large properly would be “made over and give[n] unto my beloved wife Elizabeth [Bassett] Procter and all my children,” together with all livestock and household furniture.

Later when Elizabeth and her infant son were released from jail in May 1693, and Elizabeth returned to the Proctor farm in Salem, she discovered that stepsons John and Benjamin were in possession of the Salem house and land as well as her land in Chebacco. Moreover, the stepsons had denied Elizabeth the traditional “widow’s third” of the estate. In May 1696 Elizabeth wrote out a complaint and submitted it to the General Court in Boston disputing the settlement of John’s will and also the loss of her widow’s third.

[I]n that sad time of darknes before my said husband was executed, it is evident somebody had Contrived a will and brought it to him to signe wherin his wholl estat is disposed of not having Regard to a contract in wrighting mad with me before mariag with him . . . . sinc my husbands death the sd will is proved and aproved by the Judg of probate and by that kind of desposall the wholl estat is disposed of; and although god hath Granted my life yet those that Claime my sd husbands estate by that which thay Call a will will not suffer me to have one peny of the Estat nither upon the acount of my husbands Contract with me before mariage nor yet upon the acount of the dow[e]r which as I humbly conceive doth belong or ought to belong to me by the law for thay say that I am dead in the law and therfore my humble Request and petition to this Honoured Generall Court.

Elizabeth believed that her stepsons had cheated her out of her prenuptial inheritance as well as her widow’s third, although she admitted that she knew she was still “dead to the law” and could not inherit.

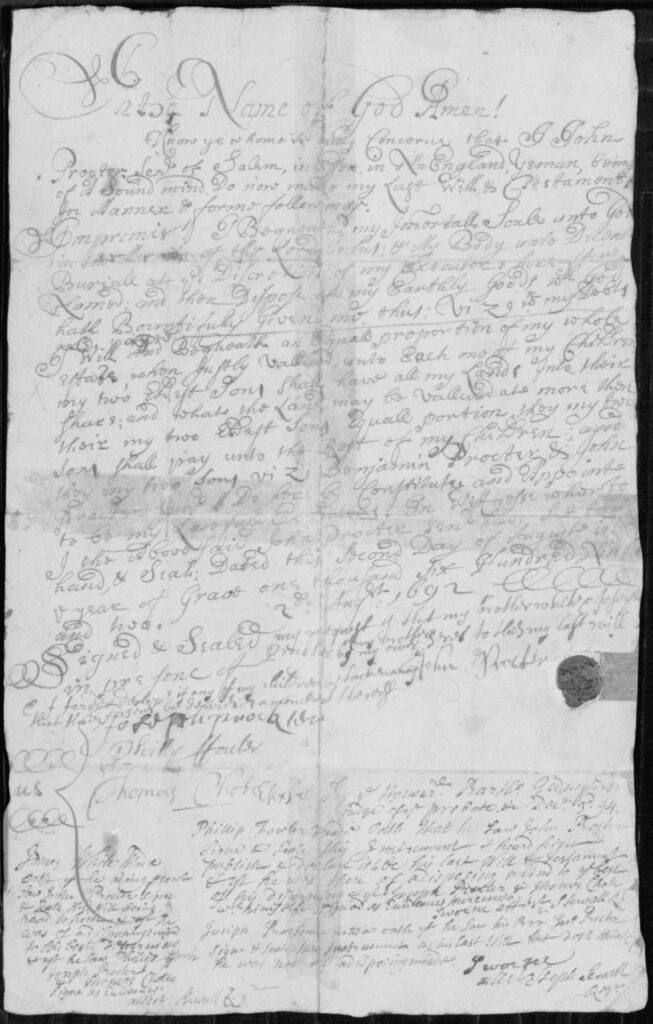

In 1692 just before John was to go to trial, his two sons from previous marriages, Benjamin and John Jr. had made out a new will, written in a clerical hand, and brought it to the jail for their father to sign. It was dated August 2, 1692, three days before his trial and conviction. The will’s key clause (at the center of the document) gives all of John’s property to Benjamin and John, Jr. as executors to distribute among their families:

I will and Bequeth equal . . . proportion of my whole estate when justly valuated unto each of my children . . . my two [eldest] sons shall have all my lands unto their shares; and they my two sons, namely Benjamin Procter & John Procter Junior, I do hereby constitute and appoint to be my lawful Executors.

Two years later, the will, which John had signed while still in shackles, was accepted by Bartholomew Gedney, Salem’s Judge of Probate, on December 3, 1694, and attested by Proctor’s friends James White and Philip Fowler, and John’s younger brother, Joseph Proctor. Both White and Fowler confirmed that John was of “disposing mind,” that is, that John was rationally capable of making a will. But Joseph took issue with this assessment and wrote a dissenting view, “I doth think that he [John] was not of disposing mind” in the bottom right of the document. What was the issue here? Perhaps Joseph believed that his brother did not fully apprehend that his previous will, which included Elizabeth as one of his heirs, would still have been valid.

Elizabeth clearly suspected that John’s two oldest sons deprived her of her rightful inheritance. On the other hand, when the sons prepared John’s will and brought it to him to sign, they rightly assumed that both he and Elizabeth would be convicted, as indeed they were three days later. Thus Elizabeth, although reprieved because of her pregnancy, would still be officially “dead to the law” and barred from all its benefits, including the right to inherit property, until her attainder was lifted. But what they may not have realized is that their father’s previous will of 1688 would still have been valid, hence Elizabeth’s petition. Either his sons had convinced him otherwise or they were simply following their father’s anxiety about the possible loss of all his property to his heirs if Elizabeth remained as one of the heirs in the will. Already in July, John believed that his right to convey his estate was in doubt, as he lamented in his petition to several sympathetic Boston ministers. The Salem magistrates, he believed, “have already undone us in our Estates.” Time was of the essence, so John assumed, and he enlisted the help of his two elder sons to make out a new will in early August just three days before in would be put on trial. On the other hand, the sons themselves may have taken the initiative to cut out Elizabeth (should she survive) and preserve the whole of John’s estate for themselves, as she later charged.

In 1696, when Elizabeth submitted her complaint, she was still under legal attainder which she acknowledged in her petition. Nevertheless, she asked the General Court to change that status and “put me into the capacity to mak use of the law to Recover that which of Right by law I ought to have for my necessary supply and support.” But there were not enough members of the Court who were sympathetic to her cause to make any change. Governor Phips, who had previously granted her a second reprieve and stopped Stoughton’s plan to execute her after she gave birth, had died unexpectedly while in London in 1694. The zealous Stoughton, who wanted “to clear the land” of witches, became the acting governor and was apparently not willing to support Elizabeth’s request to lift her attainder and restore her legal status.

A year later, however, Salem magistrate Bartholomew Gedney, as Probate Judge, tried to move Elizabeth’s case along, declaring that she was now “alive in the law, whereby to Recover her Right of Dowry,” that is, the Chebacco property, and Gedney may have informed the stepsons of his ruling. But by this time, the estate had already been apportioned according to John’s new will. Not until 1703 was Elizabeth’s attainder finally lifted allowing her to be “reinstated in their just Credit and reputation.”

In 1710 the General Court in Boston finally recognized that the Salem trials were a miscarriage of justice and authorized compensation for the families of those who had been executed and those who had been temporarily reprieved but were still under the death sentence. The government appears to have acknowledged that although Elizabeth had been condemned, she had been unfairly disinherited, and it awarded to “John Procter {wife}” £150 pounds, the largest amount conferred on any of the Salem victims, in recognition perhaps of the unfair way she had been treated. The funds were distributed to John Proctor Jr. and his brother Thorndike (another son of John’s second marriage) and to Elizabeth, who was not named but referred to indirectly as “persons Condemned & Not Executed.” How much of this sum she received is not indicated. In 1712 she appears by name, now as remarried “widow alias [Daniel] Richards” on a separate record as the recipient of these funds, together with twelve other names of Proctor family members who shared in the settlement. Still loyal to John’s memory, she may have continued to believe that he would never have stripped her of her inheritance, especially her dower. She died the same year at the age of sixty-five. For her steadfast loyalty to her husband and her persistence in seeking justice and gaining it, the John Proctor of 1692 might agree with the words of Arthur Miller’s John Proctor that Elizabeth was indeed a “marvel.”

Further Reading

For general account of the Salem witch trials, see Benjamin Ray, Satan and Salem (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015); for the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 court records pertaining to John and Elizabeth, see The Salem Witchcraft Trials Digital Archive; Arthur Miller’s “Why I Wrote The Crucible,” was published in The New Yorker, October 21-28, 1996; for John Proctor’s will of 1692, see Essex County Probate Court Papers, no. 22851:9 accessed from American Ancestors Essex County Probate Files; for John Proctor’s previous wills, 1688, 1674, accessed from Salem Deeds, Deed Book 8, pages 388-40.

Note: Seventeenth-century documents use the spelling Procter, while modern sources and Arthur Miller’s The Crucible use Proctor.

This article originally appeared in February 2023.

Benjamin Ray is the Daniels Family Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of Religious Studies, Emeritus, University of Virginia. He is the author of Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015), an associate editor of Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt, gen. ed. Bernard Rosenthal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), and Director of The Salem Witch Trials Digital Archive.