In the summer of 1953, Richard Wright left Paris for West Africa’s Gold Coast, where Kwame Nkrumah, that country’s first black prime minister, was about to make a historic bid for independence from British colonial rule. The purpose of Wright’s trip–his first to Africa–was to document Nkrumah’s political moment and to dispel stereotypical myths about the continent in the process. Yet as Wright’s reflections in the now-classic Black Power make clear, his six-month sojourn became, as well, a personal pilgrimage to an ancestral homeland. “I wanted to see the crumbling slave castles where my ancestors had lain panting in hot despair,” he wrote (6). He chose to travel to the Gold Coast by ship, then a twelve-day voyage, re-charting the course taken previously by slave ship captains and colonial officials from Liverpool in England to Takoradi in the Gold Coast.

Two summers ago, I traveled to Ghana to conduct research in the historic castles and dungeons of Cape Coast and Elmina. Since Wright’s trip forty years ago, these sites have become hugely popular with tourists. I went there to study how the curators of these sites reconstructed the history of the slave trade, and how visitors interacted with the history exhibitions and the physical environment. Specifically, I wanted to understand how visitors formulated ideas about remembrance, cultural identity, and heritage in the space of the monuments.

Like Wright’s, my trip to Ghana marked my first time in Africa and combined research with a spiritual homecoming. Prior to going, I had traveled from New York to England, where I spent several weeks examining archives and exhibitions in London, Bristol, and Liverpool, ports notorious for their connection to the slave trade. Consequently, not unlike Wright’s, my trip to Ghana originated on the shores of its former colonial ruler. Instead of traveling by ship, however, I flew from London to Accra. From there, I took a State Transportation Corporation bus, crowded with Ghanaian travelers and tourists from around the world, along the rugged, hilly coast, and saw for the first time the crumbling forts and the angry waters that still churn around them. It was a view that I imagined to be not too dissimilar to the one that my ancestors in the coffle might have witnessed centuries ago on their defiant and painful march to the coast (fig. 1).

Such journeys, unusual in Wright’s day, are quite common in ours. In recent years, increasing numbers of people of African descent, particularly African Americans, have engaged in what I call cultural heritage tourism, a type of travel-related identity seeking, where they visit monuments, historic sites, and other places of interest in an effort to get a glimpse of where they came from and an understanding of how they define themselves. The cultural heritage tourist in this case is typically middle or working class and travels as part of a group, usually a church group or an organized tour, with “roots seeking” in mind. Indeed, this type of leisure travel is also called roots tourism, in part after Alex Haley’s popular novel and later television miniseries, Roots, which spurred the first big wave of African American heritage tourism in the late 1970s, together with the designation of both Cape Coast and Elmina as World Heritage Monuments by UNESCO in 1972 (fig. 2). But while cultural heritage tourism seems to be booming, it is not for everyone. When my sister, Lisa, asked about joining me in Ghana, I mentioned my research plans at Cape Coast and Elmina. Her response was, “Cheryl, that’s depressing! Why would I want to go there and revisit that horror? That’s not my idea of a vacation.” I suggested that she could also check out a local village, the nearby nature reserve, rainforest, or beach, but being familiar with the history of coastal Ghana, she could not begin to imagine treading in waters that at one time had been so bloodied. Clearly, for some, the pain of visiting sites of such human devastation is simply too unbearable.

The attention directed towards Cape Coast and Elmina by tourists from around the globe, then, is not part of an isolated trend. Nor are members of the African Diaspora the only ones going to visit. Rather, Cape Coast and Elmina are frequented by Ghanaians, different groups of people from the African continent, and others still from around the world. This makes for an interesting mix of descendants of slave traders, both African and white European, and descendants of slaves at these popular yet controversial sites. Converging in the space of the monuments then are the contested memories of the significance of the place, different perspectives on which histories should be most emphasized, and which cultural group lays claim to them.

In other words, such sites become important battlegrounds for what I call symbolic possession of the past, that is, claiming the memory of a historic event by one social group or another. Symbolic possession of the past concerns a group’s willingness to take responsibility for its past, to (re)claim a particular slice of history that defines who they are. As victims of traumatic histories struggle to possess the sites and symbols of the past, they begin to acquire the sense of agency to shape dominant narratives and to police their history, making sure that its significance is never forgotten. Because exercising symbolic possession of the past repeatedly affirms the existence of the group, this action constantly validates the identity of the members of the group. Understanding contests for symbolic possession of the past, then, can help us understand our attachment to (or disavowal of) lost or painful histories.

At the historic castle/dungeons of Cape Coast and Elmina, the struggle for symbolic possession of the past unfolds among visitors, who draw battle lines along ethnic, racial, national, gender, and class divides. Furthermore, the battle for symbolic possession of the past involves government officials and museum professionals, for it is at the center of the controversy over how these sites are treated as memorials (or not) and whose and what memories are represented there for tourist consumption. As I learned on my journey, no one group controls the symbolic possession of these monuments. Rather there exists an often contentious joint partnership, one that is fluid, shifting between many different interests, different features of the sites, different pasts. Wright’s questions to himself before embarking on his trip to the Gold Coast laid out the complexity of the dilemma at hand: “Perhaps some Englishman, Scotsman, Frenchman, Swede, or Dutchman had chained my great-great-great-great-grandfather in the hold of a slave ship; and perhaps that remote grandfather had been sold on an auction block in New Orleans, Richmond, or Atlanta . . . My emotions seemed to be touching a dark and dank wall . . . But, am I African? Had some of my ancestors sold their relatives to white men? What would my feelings be when I looked into the black face of an African, feeling that maybe his great-great-great-great grandfather had sold my great-great great grandfather into slavery?” (4). Such questions still haunt today’s African Diaspora tourists, nearly four decades later.

The Price of the Ticket

Upon entering the monuments of Cape Coast or Elmina, visitors first become aware of themselves as a particular type of tourist–Ghanaian national or non-Ghanaian national–based on the price of the admission ticket. Non-Ghanaian nationals pay ten times more than Ghanaian nationals: ten thousand cedis (approximately four dollars) instead of one thousand cedis (approximately forty cents). Officials of the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (GMMB) defend this pricing structure, which discriminates based on class and national belonging, as necessary to support the maintenance and upkeep of the monuments, a strategy not uncommon to nascent tourist economies in other developing countries. At one thousand cedis, a visit to Cape Coast or Elmina is within reach of many Ghanaians, enabling them to participate in the development of the tourist economy, while lending support to the monuments’national importance. The GMMB spokesmen assert that tourists coming from as far away as New York City or Auckland can afford to pay ten times more than the admission price paid by Ghanaians.

Many non-Ghanaian nationals, especially those from the African Diaspora, expressed great dissatisfaction with the admissions fees at Cape Coast and Elmina. Simply put, they felt that it was unfair that they should have to pay more. Indeed, many African Americans and blacks from the diaspora assert that their historical relationship to the monuments in Ghana is the overriding difference. For them, the monuments are distinctive sites that they journey to in search of some aspect of their identity, a clue that will unlock the mystery of their past, something that will connect them to their ancestors. Many African Americans claim that it is hard enough for them make the pilgrimage to redeem this part of their history, to “come home” and to pay homage to their ancestors, without feeling doubly wounded by the unequal admission prices. During her visit to Cape Coast Castle in 1998, Farah Jasmine Griffin, who teaches English at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States, asked, “Why do Africans in the diaspora have to pay so much more when our ancestors were held captive here?” As descendants of enslaved Africans then, coming (home) to reconnect with their lost ancestors, many members of the African Diaspora claim a privileged status. Moreover, some reason that if they are making such a homecoming, why should they have to pay anything whatsoever to enter? Why aren’t they welcomed home with open arms and regarded, as Richard Wright wondered, as “lost brother[s] who had returned?” (4).

This question illuminates the very problem. African Americans have certain expectations when they go “back” to visit a place that has come to stand for the homeland of their ancestors. In Ghana, they feel a definite connection not only to the people and the land, but to the dungeons, those bold, physical markers of the past. Ghanaians, on the other hand, do not necessarily appreciate African Americans’ symbolic relationship to the castle/dungeons, their need to cling to something there that may explain their African heritage and anchor their sense of belonging in the world. Some Ghanaians point to a certain lack of specificity when blacks from the diaspora claim Ghana as their ancestral home. They wonder, why Ghana, and not another West African country? Why not Nigeria, Gambia, Angola, or Senegal, for example?

As such questions remind us, Ghanaians and African Americans have understood the histories of slavery and the slave trade in very distinct ways, from opposite sides of the Atlantic. And, perhaps, from opposite sides of the coin of memory. If African Americans long to remember, many Ghanians need to forget. Perhaps one of the few ways that the people who remained in present-day Ghana managed to survive the trauma of the slave trade was to suppress the memory of how it forever transformed their culture, society, land, and people. They had to forget in order to survive, to move on, and to build a new identity. They had to forget the wrongs that were perpetrated against them by white Europeans and Americans, as well as their own forefathers. Many Ghanaians I asked about this responded, “Four hundred years is enough”–enough talking about it, enough shame, enough painful memories. In contrast, most African American visitors to Ghana believe that the very act of visiting the castle/dungeons demonstrates a certain responsibility for their history, a reclaiming of the past. While many remain perplexed by the cost of admission at Cape Coast and Elmina, others see this relatively nominal fee as the small price they have to pay in order to help preserve the monuments for generations to come. Seen as a charitable donation, their contributions play the double role of honoring the memory of their ancestors while supporting the livelihood of their Ghanaian brothers and sisters. This ongoing debate is an example of how symbolic possession of the past shapes the present with such a seemingly petty thing as the price of a ticket, even when the top price is only four dollars.

What’s in a Name, I

African Americans and black people from the diaspora often have great expectations for their first visit to Africa. Whether the destination is Ghana, Kenya, or Nigeria, visitors’ hopes are connected to their desire to answer questions about their ancestry. Wright, when reflecting upon the prospect of going to Africa for the first time, gave the question of homecoming serious thought: “Africa! Being of African descent, would I be able to feel and know something about Africa on the basis of a common ‘racial’ heritage? . . . Or had three hundred years imposed a psychological distance between me and the ‘racial stock’ from which I had sprung? . . . Was there something in Africa that my feelings could latch onto to make all of this dark past clear and meaningful? Would the Africans regard me as a lost brother who had returned?” (4). Unfortunately for Wright, the answer to his last question would be no. Dressed neatly in a khaki safari outfit, sun hat, sunglasses, and camera, Wright was regarded as Western and wholly foreign by most of the people that he met in the Gold Coast.

Today, the same holds true for many African Americans and black people from the diaspora who travel to Ghana in search of their roots. What these twenty-first century pilgrims believe to be a return “home” is exposed as a mere tourist excursion upon their arrival. Regardless of skin color or manner of dress, black people from the diaspora are considered just as foreign as the average tourist from Asia, Europe, or the Americas. To Ghanaians, the tourists–black and white alike–are obruni, a term that carries the double-edged meaning of both “white man” and “foreigner.” Whether they hear the term when they go to purchase a bottle of water from a street vendor, or as they are confronted by the sea of small children who huddle outside of the monuments at Cape Coast and Elmina asking for American money and addresses, diaspora blacks can’t help being unnerved by the irony of this innocent name.

What’s in a Name, II

The original name for Elmina, Saõ Jorge da Mina, pays tribute to the patron saint of Portugal, St. George, and harks back to its initial function as a fortified trading post within close proximity of the gold mines near the Prah River in present-day Ghana. Built in 1482 by Portuguese soldiers, masons, and carpenters, it remains the oldest and largest colonial structure in sub-Saharan Africa, and one of the world’s important medieval castles. Even Richard Wright was seduced by its mere presence: “I reached Elmina just as the sun was setting and its long red rays lit the awe-inspiring battlements of the castle with a somber but resplendent majesty. It is by far the most impressive castle or fort on the Atlantic shore of the Gold Coast” (383). Elmina had to be both immense and imposing. Impenetrable even (fig. 3).

With the reluctant permission of the local village chief, Elmina was built into the rocky coastline on a narrow peninsula where the Benya River meets the Gulf of Guinea. Underground storerooms and dungeons were carved out of the stone. These were used for Portuguese trade goods, such as linen, brass manilas, and earthenware, and for the local resources received in exchange: first gold, salt, and ivory, and then human beings.

Elmina’s strategic location was a reminder for rival European nations, who were vying to break the Portuguese monopoly over the vast new supplies of gold, and for the local inhabitants, who weren’t altogether happy with the presence of a foreign stronghold in their midst. The site long since had been the center of commerce for a small fishing village, split geographically by the Benya Lagoon and politically between the Eguafo and Efutu States. By sea, Elmina was sheltered by the treacherous, rocky coastline. By land, approximately three hundred feet away as the crow flies, a steep hill, perfect for keeping watch, provided additional protection. On top of this hill, the Portuguese built a church in 1503, from which missionaries converted and baptized the local villagers, including the paramount chief (fig. 4).

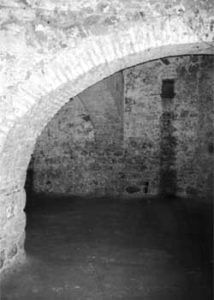

Destroyed in battles with the Dutch by the end of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese church was later rebuilt in a courtyard within the fortified walls of Elmina Castle, where it was surrounded on three sides by cavernous dungeons that held African men bound for slave ships (fig. 5).

After the Dutch finally seized Elmina in 1637, it was expanded to include a Dutch chapel. The Portuguese church became an auction gallery and later, an officer’s mess hall. After nearly 150 years of maintaining colonial headquarters at Elmina, the Dutch relinquished the castle to the British in 1872, who turned it over to the newly independent Ghanaian government of Kwame Nkrumah in 1957.

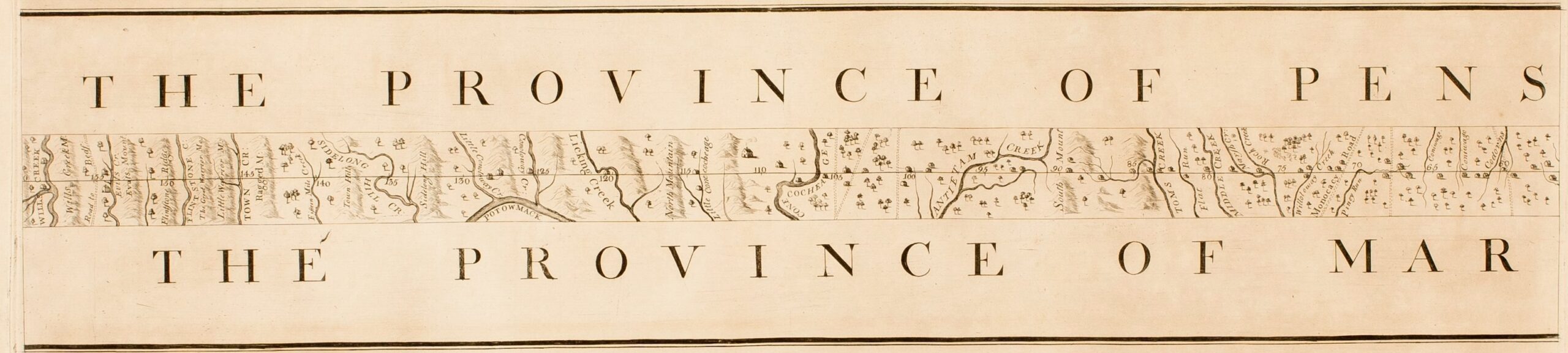

On a clear day, it is possible to see Elmina from Cape Coast Castle, located just a few miles to the east. Cape Coast began as a Portuguese trading lodge in 1555. Strategically situated on a rocky promontory with an adjacent natural harbor, it was called Cabo Corso, or short cape, by the Portuguese. For nearly one hundred years, rival European nations fought for control of Cape Coast until 1653, when the Swedish signed a treaty with the Efutu paramount chief to build a permanent structure named after King Charles X of Sweden. Over the next decade, more skirmishes ensued between the Dutch, the Efutu chief, and the Danish. But the final European power to take the fort would be the British, who captured it in 1665 and named it Cape Coast (fig. 6).

The British were quick to make significant reinforcements to Cape Coast, increasing both its size and strength to compete with the headquarters of the Dutch West India Company just a few miles away at Elmina Castle. The architectural improvements greatly enhanced the total surface area of the castle to include additional officers’ barracks, trading rooms, underground cisterns, more cannon, and taller battlements. Not only did the British hope to remain in control of this strategically positioned fort, they also aimed to establish a dominant presence on the West African coast. By enclosing virtually all the necessities of a small city within the walls of the expanded Cape Coast Castle, the British protected themselves against attacks from local and European enemies, and efficiently refined the business of the slave trade through what an economist might call vertical integration. Cape Coast remained a central conduit for the extremely high volume of British slave trafficking until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Beginning in the mid-1820s, Cape Coast served primarily as an administrative headquarters, first over British forts in West Africa and then as the initial seat of government for the British Gold Coast Colony in 1872. Cape Coast Castle remained under British colonial rule until Ghanaian independence in 1957.

According to the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board, there are only three structures designated as castles among the sixty colonial forts that remain on Ghana’s coast: Elmina, Cape Coast, and Christianborg. Of the three, Cape Coast and Elmina are the most popular with present-day tourists. By default, Christianborg is virtually off limits to tourists and photography because it houses the Ghanaian head of state. Of Danish origin, Christianborg was built in 1661 at Osu in the capital city of Accra. As a fortified structure that once held African captives in a complex matrix of dungeons, it might seem a bit odd that Christianborg Castle is now home to the president of Ghana. But equally perplexing for today’s roots tourist is the very term “castle.”

The word castle dates from before the twelfth century. From the Latin castellum or fortress, a diminutive of castrum, meaning fortified place, the word castle signifies “a large fortified building or set of buildings.” Over the past three hundred years, Christianborg, Elmina, and Cape Coast have been classified as castles for their style of architecture, their sheer size, and their function. Distinguished from the more numerous but smaller forts, the castles have a larger surface area, a more intricate complex of connecting structures, and the ability to house a large number of people. Yet the word rings oddly in many visitors’ ears. African Americans and many blacks from the diaspora feel that calling Cape Coast and Elmina by the name “castle” elides the history of the dungeons beneath these places and with it, their ancestors’ experiences. With such a name, they say the stories of their forebears get lost. In their place, fairytale notions of European architectural grandeur associated with a popular understanding of the term “castle,” sugarcoat the fact that enslaved Africans, possibly their ancestors, were held captive there.

Just as they reject the label “castle” to describe sites like Elmina and Cape Coast, some members of the African Diaspora also disagree with the renovation efforts being made in the name of historic preservation. They feel that the renovations privilege high architecture and transform the castles into “make believe” places. One visitor plainly stated, “It is horrible to watch this dungeon being turned into a Walt Disney castle!” referring to coats of fresh white paint on the bastions, the addition of potted plants and flowers at the entrance, and the effort to clean and paint the inside of the dungeons. The double-edged phrase, “Stop white washing our history!” appears frequently in the visitor comment books at Cape Coast and Elmina. Instead of the regular program of painting, upkeep, and renovation, some feel that these monuments should be left alone to crumble and fall into the sea (fig. 7).

Other African Americans have recommended that the word “dungeons” be added to the official name of Cape Coast Castle and Elmina Castle. Their suggestion seeks to recognize the memory of the millions who were held captive there. But considering the GMMB’s marketing efforts aimed at international tourism, a name like Cape Coast Castle and Dungeons might not be so good for business.

Performing Memory, Performing Race, Performing Identity

Upon entering Cape Coast or Elmina, visitors are invited to see and participate in layered and nuanced performances of remembrance. First, they become aware of themselves as a particular type of tourist–as Ghanaian nationals or non-Ghanaian nationals–based on the price of the admission ticket. Then, as if to prepare visitors for the horror of the dungeons, to soften the emotional blow that they are about to experience, they are directed to visit a museum before going on a guided tour of the castle.

In order to reach the museum at Cape Coast Castle, visitors must walk across an expansive, cobblestone courtyard that opens out to the sea. The museum is located on the second floor in cool, darkened rooms that formerly engaged the business of the slave trade and the administration of the British Gold Coast Colony. Upon entering the museum, most visitors experience momentary blindness as their eyes become accustomed to the sharp transition from brightness to darkness. Outside, pure, equatorial sunlight reflects off the whitewashed exterior of the castle and the crashing sea, providing a high contrast with the simulated museum environment lit in deliberately low lumens in order to protect the artifacts on display. Other contrasts of light and dark are found throughout the tour of the castle, most obviously between the gloom of the dungeons and the intensity of the sun in exterior spaces–or metaphorically, between blacks and whites (fig. 8).

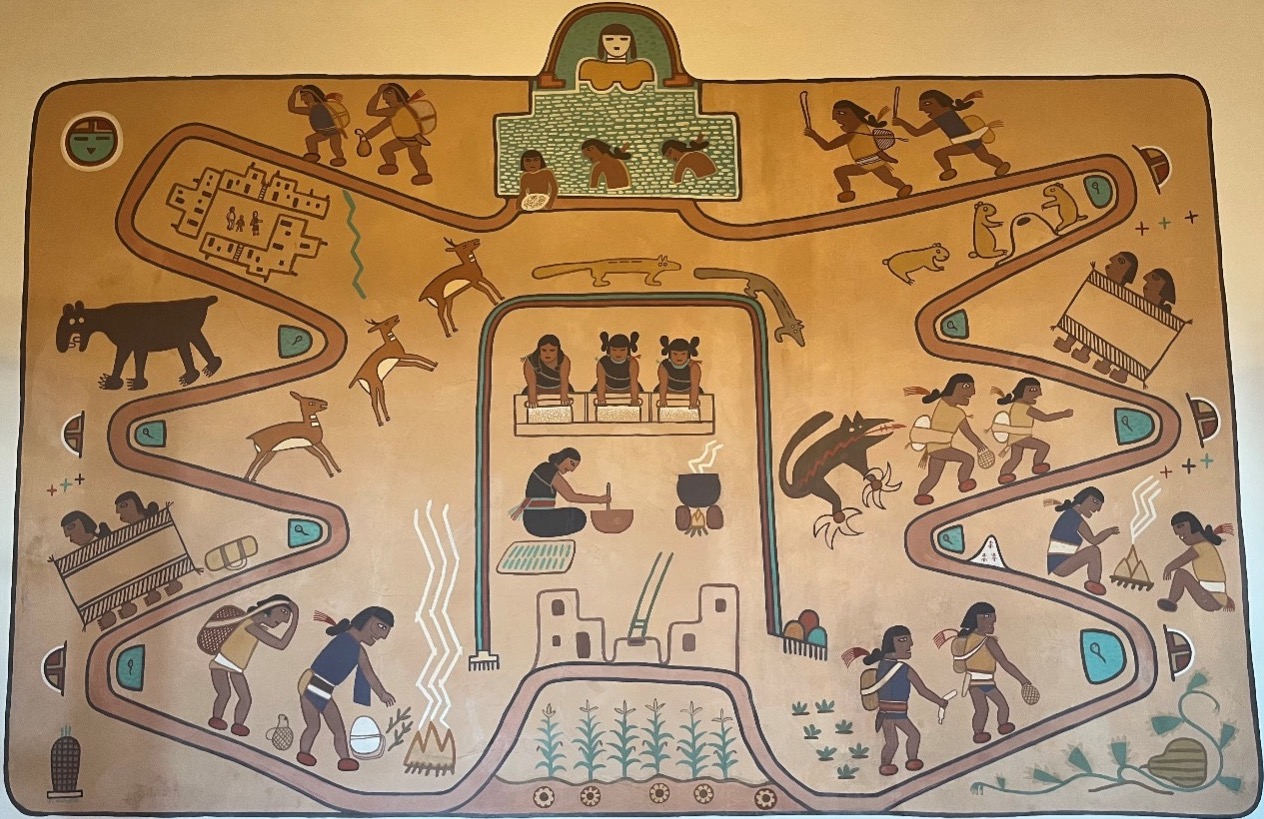

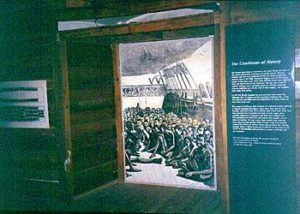

According to the curators, the museum’s exhibition, Crossroads of a People, Crossroads of Trade, “examines more than 500 years of Ghana’s history, placing the castle within its broad economic, political, and historical contexts, including the legacy of the slave trade. It also offers a glimpse into the life today and the rich cultural heritage of the Central Region.” The exhibition was developed in 1994 in close consultation with North American advisors, designers, curators, and historians, as well as local and national scholars, chiefs, and archeologists. Crossroads begins with the pre-colonial history of the Central Region of Ghana, using artifacts, such as gold weights and measuring scales, stone implements for hunting, and terracotta figurines. The coming of the Europeans is represented by large blowups of European engravings that depict West African scenes or West African/European contact. The development of the slave trade is told through maps of the trade routes, engravings of the coffle marching through the hinterlands, and examples of the artifacts of barter and exchange–glass beads, pottery, whiskey bottles, and firearms. Midway through the exhibition, visitors pass through a dark, wood-paneled space meant to represent the hold of the slave ships in which captive Africans were forcibly transported to the New World. Walking through this cramped, minimally designed space, visitors are confronted with a heap of heavy rope from a ship, a pair of shackles connected to chains, and other iron restraint devices, which are fastened to the raw hewn wooden walls. One section of the wall has rough, wooden planks meant to resemble the narrow decks on which enslaved men, women, and children were closely confined. There is also a large black-and-white print of the slave ship icon and two popular nineteenth-century engravings of captives onboard a slave ship. Overhead, a wooden grate simulates the hatch that would have brought in fresh air from the ship’s upper deck (fig. 9).

Equipped with artifacts, illustrations, and a faint musty smell, this fabricated, transitional space is obviously meant to impress upon the visitor’s imagination the horror of the Middle Passage. Similar installations replicating the hold of a slave ship have been utilized by museum professionals in England and the United States, often to great effect. But here, ironically, such an installation fails to have the same impact because the main attractions–the physical edifice of the castle and slave dungeons–are themselves so real and tangible that they need no theatrical accompaniments. They provide the “authentic” experience.

Upon exiting the “hold,” the visitor is thrust immediately upon a simulated auction block in the Southern United States. The transition is abrupt, and not without impact. The next room summarizes the trials and achievements of New World blacks, using black-and-white photographs or engravings of notable people. These images visualize moments of African Diaspora history in the Caribbean and North America, from the Haitian Revolution to the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. There are familiar portraits of people like Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, Duke Ellington, Billie Holliday, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jesse Jackson, Angela Davis, and Bob Marley. Although many of these people are well known in Ghana and around the world today, this part of the exhibition has a distinctly American and mostly masculine feeling. The last part of the exhibit describes the contemporary cultural history of Ghana and the Central Region using examples of local crafts, including brightly colored cloths and carved wooden utensils and musical instruments. With a mood that is upbeat and exuding vitality, this closing section ends with explanations of local and national traditions, economy, politics, and agriculture.

The museum at Elmina is much smaller and less sophisticated, and its focus on local history instead of larger history of the slave trade gives it special charm for many tourists. It is located on the first floor of the former Portuguese church, a squat red-brick building that dominates the central courtyard. The exhibit, Images of Elmina across the Centuries, charts the history of the village of Elmina from pre-colonial times to the present. Opened in 1996, the exhibition was organized by the GMMB in conjunction with the same group of American consultants that advised the Cape Coast design team. Using little in the way of complex design or theatrical installations, the Elmina exhibit effectively employs two-dimensional illustrative materials–mostly prints, photographs, and text–on large folding panels to relate an intimate local history. At the museums at Cape Coast and Elmina, the influence of Western consultants is notable in the design, layout, and type of art and artifacts selected to relate the histories.

After visitors take in the exhibitions at either Cape Coast or Elmina, they go to meet a tour guide in the courtyard. Each tour guide leads a group of about twenty people, which usually ends up being racially and ethnically diverse as well as international in character. Diversity doesn’t mean harmony, however. Indeed, some members of such mixed tour groups complain of being singled out by other visitors in their groups for derogatory comments. An American tourist from Connecticut briefly described his experience during an Elmina Castle tour in the site’s logbook: “Very impressive castle. Tour was very good. Great views toward the city, beach and ocean. One concern–a man during the tour was distracting an[d] I felt offended by his anti-white sentiments, as he kept saying, ‘white people this . . .’ I couldn’t understand exactly, but he should respect other people more who are trying to follow the tour guide. Overall, I enjoyed my visit here.” A Ghanaian member of the same tour group added, “[I]t should be strictly forbidden for visitors in the group to keep making offensive comments which directly or indirectly concern individuals in the group.”

Organized tour groups often request to have their own guide. These groups are usually more homogeneous, either racially, or by their affiliation with schools, churches, or missionary organizations. Often, organized groups of African American tourists ask that no white people accompany their tour. One African American visitor to Cape Coast suggested, “White visitors should come on different days than the black visitors.” In addition, some African American groups request that no white people be present when they go to the dungeons for the first time, explaining that they don’t want to experience the pain of their ancestors with a descendant of the oppressor present. One African American visitor to Cape Coast expressed his feelings of “rage and hostility towards the Dutch and Portuguese”–past and present–after going on the tour.

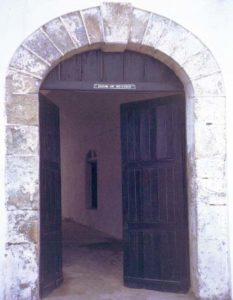

The guided tours at both Cape Coast and Elmina focus on the points of pain and suffering, and of strength and resistance, to lend a sense of authenticity to the historical and contemporary significance of the sites. Indeed, the notion of authenticity is central to the allure of cultural heritage tourism as an industry. In their efforts to show “how it really was,” the principal highlights of the castle tours dramatize key features that offer up a notion of life as it was once experienced there. Thus, visitors learn about how enslaved women were raped by European traders, governors, and officers and about the types of torture inflicted upon defiant captives. They also sense the ironic presence of the church inside the castle, and the dramatic contrast between the spacious governors’ and officers’ quarters on the upper levels and the stench and horror of the underground dungeons. Perhaps most disturbing, and in this sense most authentic, is the visitor’s final glimpse of the “Door of No Return,” from which enslaved Africans were led to awaiting ships, never to come back.

Most, if not all of the rooms that tourists pass through are empty. The churches have no pews. Nor are the governors’ or officers’ quarters decorated with period furniture. This means that visitors have to imagine what it might have been like to live in these spaces. One visitor at Cape Coast demanded: “Please authenticate the Governor’s residence to look exactly the way it was then. I think that will make the necessary contrast with the dungeons.” When I visited Cape Coast Castle, restorations to the governor’s quarters, which were scheduled to include arrangements of furniture and decorations from the colonial period, had begun. At Elmina, there was talk of restoring the two tower prisons on top of the seaward bastions in which the Asantehene or king of Ashanti, Prempeh I, and his royal family were held by the British for four years at the end of the nineteenth century. These restorations would likely aim to give a sense of Ashanti culture, in particular of the way in which a turn-of-the-century royal Asantehene lived. Such a restoration, focusing on the history of a known national figure, would provide a powerful contrast to the better-known stories of the colonial officials who occupied the second-story living quarters. It’s relatively easy to imagine how to restore the quarters of the colonial and local elites.

But how might the dungeons be “authenticated”? A visitor to Elmina had one possible solution: “Renovate with models of slaves, sound effects, [and] smells to give authenticity and real feel for what it was like for our ancestors.” But might such a renovation go too far? How would the curators and designers choose the models to represent the slaves? Would they opt for wax figures of the type seen at natural history museums or at the popular international tourist attraction, Madame Tussaud’s? Or might they use actual people to make the body casts? This was the case at the Museum of African American History in Detroit, where city residents were used as models for the life-sized figures of fifty shackled youths, cast in bronze. Until recently, these figures were part of a central exhibit about the Middle Passage, now being demolished due to its lack of popularity with visitors. Some of the restorative changes to the female dungeons at Elmina aim at the kind of authentication the visitors’ logbooks call for, especially the new metal bars that were placed in the arched window openings (fig. 10).

But the fresh coats of white paint inside of some of the male dungeons have left many visitors in a state of outrage. As one person commented, “The Jews would not paint the ovens in Germany!” What is more, when one of the male dungeons at Elmina was remodeled into a gift shop, so many visitors complained about it that it was eventually dismantled and moved to an outer service area across from the castle restaurant. They felt that the presence of a gift shop in a former dungeon not only trivialized, but also erased the memory of those who were once held prisoner there. Moreover the bitter irony of a dungeon-cum-gift shop drew attention to the consumer side of the monuments as tourist attractions.

But the deepest sense of irony becomes clear when we consider the way in which the monuments are packaged and marketed for global tourism, especially for cultural heritage tourism. Here, the thing that is being sold (back) to the tourist is the memory of their ancestors: the now-absent black bodies that become part of the allure of these monuments. It is an irony some visitors to the castles have complained about. As one person put it, “Don’t turn our memories into a tourist attraction.” In the current age of global tourism, memory itself becomes a commodity–a thing to be bought, sold, and traded.

At Cape Coast Castle, a different type of authentication takes place inside the male dungeons. A large altar to the local god, Nana Tabir, has been erected in front of the blocked entranceway to an old tunnel leading to the Door of No Return. One of the oldest gods of Cape Coast, Nana Tabir was known to protect the local fishermen as well as the traders who met in Cape Coast Castle. The god took the form of a sacred rock, the very rock from which the dungeons were carved during the late seventeenth century. The present shrine to Nana Tabir was erected by the chief of Cape Coast, Nana Kwesi Atta, to replace the one that was there prior to the construction of the dungeons and castle. The altar is decorated with candles, flowers, fruits, notes, and monetary offerings from visitors. It is attended by a local priest, who will say a prayer to Nana Tabir in exchange for a donation.

There have been mixed reactions to the presence of the altar deep within the cavernous male dungeon. Some feel that the monetary donations, often urged by the tour guide, have made the dungeon commercial. Others, including local Christians, dismiss it as simple idolatry, while local believers in the panoply of household and state gods feel their beliefs are given notice at Cape Coast Castle. Yet many black people from the diaspora find the presence of the altar comforting. It is a place where they can bring offerings to their lost ancestors. For them, it takes on a different, double meaning, serving as an altar to Nan Tabir as well as a shrine to the people once enslaved there.

Elsewhere, the dungeons are left hauntingly bare, with the exception of the wreaths, flowers, notes, and burning candles left on a daily basis by visitors. And most people seem to prefer the dungeons that way. They feel that the emptiness best signifies the absence of the many millions gone. For them, empty is the only authentic way for the dungeons to be represented. Visitors regularly choose the emptiness of the dungeons to perform rituals of tribute and commemoration. Some burn incense there. Others weep, almost incessantly. Some groups recite poetry, sing songs, or pray together. What sound effects could compete with the cries, shrieks, chants, prayers, and songs of today’s visitors? What could be more “authentic”?

Photographic Memories

At the castles, visitors are permitted to take photographs free of charge. Throughout the tour, guests are constantly seen taking pictures of the historical points of interest, members of their group, or details of architectural or aesthetic import. Often, they choose the most picturesque vistas to make their photographs. At Elmina, the most popular places for taking pictures include the courtyard with the view of the Portuguese church, the northeast bastion with views of Fort St. Jago and the fishing village of Elmina, and the front entrance with the medieval drawbridge (fig. 11).

At Cape Coast, the most photographed spot is the balustrade walkway lined with cannon, which boasts a dramatic view of the ocean. The irony of the visitors’ fascination with taking photographs at these monuments is echoed in the sentiment of one tourist who noted, “The disparity between the horrific history of the castle and the natural and physical beauty of the seashore is a difficult mix for the present day visitor.” Seemingly attracted by the “physical beauty” alone, some visitors come with sophisticated view cameras, tripods, and black-and-white film to make “art” photographs of the castles and the surrounding environment. In fact, many fashion photographers have chosen the castles as stylish backdrops for their glossy magazine work (fig. 12).

In a strange way, then, the horror of these monuments becomes aestheticized in the act of making photographs. Even Richard Wright was taken by the hypnotizing beauty of Elmina: “Towers rise two hundred feet in the air. What spacious dreams! What august faith! How elegantly laid-out the castle is! What bold plunging lines! What, yes, taste” (384). Wright’s own photographs of Elmina emphasized the symmetry of the walls. It is significant that most people do not return to the dungeons to make photographs, nor do they take many pictures there at all. Perhaps this is in reverence to “the ancestors,” or for more practical reasons, such as the lack of sufficient light. The bright flashes needed to get a decent photograph in the darkness of the dungeons would not only disturb the somber mood for other visitors, but would surely ruin the “authentic” gloom cast by the deep shadows (fig. 13).

Without a doubt, snapping photographs has become a required part of the tourist experience. But, in the case of roots tourism, it has a special commemorative function, a different familial appeal. As roots tourists gather in front of the cannon at Cape Coast Castle or the Portuguese Church at Elmina, they are consciously participating in an act of remembrance–symbolically taking possession of the past. Their photographs are evidence of a return to the ancestral homeland, of the buildings that still stand as a reminder of the birth of the African Diaspora in the transatlantic slave trade. Back home, they share their snapshots with family and friends as proof of having been there, of having walked through the Door of No Return. Of having “returned home,” and then returned home.

In fact, the Door of No Return is one of the popular–almost required–sites that roots tourists choose to record on film (fig. 14).

At Cape Coast Castle, the Door of No Return is located at the base of the central courtyard, just beyond the female dungeons. The enormous arched doorway encloses two impressive black doors. At the top of the doorframe, a standard GMMB sign labels the door in neat white letters, “DOOR OF NO RETURN,” marking it as a site of special interest. At Cape Coast Castle, the Door of No Return is often the last stop on the guided tour, a climactic moment where visitors watch in quiet anticipation as the guide opens the door to reveal the expanse of angry sea where enslaved Africans would have been led to awaiting ships. After the group walks across the threshold to the beach, the guide points out other places of interest that lie outside the castle walls. Meanwhile, local children, who know to wait for the opening of the door, try to engage tourists in conversation or ask for money. Some groups of cultural heritage tourists choose this spot for pouring libations to ancestors.

Finally, as the guide motions to the group that it is time to go back inside, he points out a relatively new sign above the door, visible from the outside upon reentry. In the now-recognizable neat white lettering, it reads, “DOOR OF RETURN” (fig. 15).

Placed there as a gesture of reconciliation, the guide explains that is meant to welcome back the thousands of African Diaspora tourists who flock to the monuments each year.

But is such a return really possible? Think about it. What does it mean to rename the infamous DOOR OF NO RETURN, the DOOR OF RETURN? Is the sign simply a marketing tool aimed at the African Diaspora segment of the tourist industry? Does such an act signify an attempt to erase the brutal history of the castles and the dungeons beneath them? Does it mean that time–four hundred years–has healed the wounds? Is it asking us to forget and move on?

Choosing the Perfect Souvenir

Before leaving, most visitors stop by the gift shop to purchase post cards, tourist art, textiles, jewelry, carved wooden sculpture and T-shirts. Some of the T-shirts bear slogans echoing pressing issues of debate for black Americans, such as reparations for slavery. One T-shirt for sale read: front, “Back to our heritage, Elmina Castle, 1482,” with an illustration of the castle; and back, “Damn right! Our people worked for 400 years without a paycheck. Reparations are due!” One of the popular books sold in the gift shop is Castles & Forts of Ghana, written by prominent Ghanaian archeologist, Kwesi J. Anquandah and illustrated with seductive color photographs by Thierry Secretan. Published by the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board, the book has the strange feeling of being part colonial/architectural history, part travel brochure. With photographs of whitewashed forts drenched in the pink light of sunset, it succeeds in glamorizing the forts, making them a desirable tourist destination. Moreover, like the renamed Door of Return at Cape Coast Castle, this book seems to be targeted towards the returning African Diaspora. Even the souvenirs that visitors choose to purchase are telling indicators of their own need to symbolically possess the past.

Upon leaving, visitors are invited to list their nationalities, names, and addresses and to write their impressions of the tour and the castle in comment books placed on the podium just by the entrance. The comment books serve as a census of visitors and their impressions. They help site administrators, curators, and the GMMB gauge visitors’ approval of the job they are doing. At the same time, the comment books often satisfy visitors’ needs to express their feelings after cathartic experiences in the dungeons. Writing about their experiences helps them to begin the process of making sense of their visit. The comments left in these books form a continuing dialogue, one that is often played out over days, weeks, and months as successive visitors respond to the comments of those that came before them. While seemingly an innocent gesture on the part of the GMMB to document its visitors, the comment books are the place of many discussions about race, history, politics, and commemoration. It is here that the visitors’ final performances of remembrance, race, and identity are recorded.

No Place Like Home

The castles and forts of Ghana always have been sites of African/European contact and centers of cultural exchange. While their fundamental role in facilitating the slave trade is undeniable, it is important to bear in mind that they also served many different purposes, often simultaneously. During the period of the slave trade, Cape Coast Castle served as defense against rival competitors, a prison for the enslaved, a residence for foreign workers and visitors, a trading hall, a warehouse, a court of mediation, a dining hall, a place of worship, a missionary school, and a meeting place for local and foreign dignitaries. Thus, in one way or another, priests, slaves, doctors, carpenters, servants, traders, cooks, kings, and schoolchildren might have interacted with each other and occupied the same space.

The castles and forts developed a symbiotic relationship with the towns that grew around them, relying upon them for their work forces, housing stock, food production, and natural resources. Moreover, in response to the needs of local, national, or international interests, these buildings were continually adapted and converted to different uses. Likewise, the local economy shifted and changed. Today, the castles and the cities that surround them remain almost inseparable–spiritually, economically, and intrinsically. In the case of Cape Coast and Elmina, they share the same name; they thrive off of one another and it has long been that way. For nearly thirty years, the castles have been steadily renovated to prepare for their latest incarnation, as World Heritage Monuments. Following suit, the towns around them have shifted their economies towards tourism, with the construction of world class hotels and resorts, the preservation and restoration of historic architecture, the opening of new restaurants, the development of walking tours, a new international performing arts festival–Panafest–in 1992, and the improvement of roads and infrastructure. The castles indeed forge a sense of community, albeit one filled with contradictions.

Until recently, local inhabitants understood the historical function of these buildings to be fluid and constantly changing. But since the forts and castles were designated as World Heritage Monuments–a term that requires that they be preserved and conserved for the understanding of future generations of the international community–the multiplicity of meanings and uses that they once shared has dwindled. Designated as World Heritage Monuments, the forts and castles are marketed to tourists as memorials to the victims of the slave trade.

Many African American visitors to the Cape Coast and Elmina see these sites as tangible and necessary memorials, some of the very few places where physical evidence of their heritage can be seen, touched, walked through, and experienced with all of their physical senses. For them, having a physical place to link to their bodies–to the way they imagine the past–is the primary reason for their visit. There is something about the significance of a place for people who cannot trace their ancestry specifically, but know that their people at one time came from that place, passed through its doors, suffocated in the stench of its dungeons, were raped in the governors’ quarters, and carried across the still-turbulent sea just outside the Door of (No) Return. These pilgrims, by “returning” to, or making recuperative homages to the dungeons, are staking a claim for their history, symbolically taking possession of their past. Their individual acts of performing memory–walking through the dungeons, leaving memorials, lighting candles, saying prayers, taking photographs, and writing about their experiences in the visitor comment books–leave physical evidence of their visits to these monumental memorials (fig. 16).

Their individual acts of remembrance and interaction with others like or unlike them speak to the power that physical places have for the articulation of memory and identity.

Further Reading:

The remarks by Richard Wright can be found in his Black Power: A Record of Reactions in a Land of Pathos (1954; reprint, New York, 1995); the comment by my sister, Lisa Lennon, was made in a personal communication, May 1999; opinions of the GMMB regarding the development of tourism at the forts and castles, the attitudes of Ghanaian and non-Ghanaian visitors, and the various restoration and renovation projects were obtained in interviews with Nana Ocran, director of education, Cape Coast Castle; Stephen Korsah, tour guide, Elmina Castle; and Gina Haney, US/ICOMOS, August 1999. Opinions of tourists were obtained in interviews conducted in August 1999 or from the visitor comment books. The viewpoints of people living in Cape Coast, Elmina, and other neighboring villages regarding the castles, forts, and tourism were obtained in interviews in August 1999. The comment by Farah Jasmine Griffin was obtained from the visitor comment book and in a personal communication, April 21, 2001. For aspects of architectural and cultural history of the forts and castles see, for example, Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles & Forts of Ghana (Accra, 1999); Albert van Dantzig, Forts and Castles of Ghana (1980; reprint, Accra, 1998); and J. Erskine Graham Jr., Cape Coast In History (Cape Coast, 1994). For a general history of Ghana, see for example, F. Buah, A History of Ghana (New York, 1980) and F. Agbodeka, An Economic History of Ghana (Accra, 1992). For a general history of the slave trade see, for example, James A. Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History (New York, 1981); Philip D. Curtin Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (Madison, Wisc., 1969); Roger Anstey, The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition 1760-1810. For Dolores Hayden’s comment regarding place memory, see her Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (Cambridge, Mass., 1995). For more on cultural heritage tourism, see James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1997); Edward M. Bruner and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “Maasi on the Lawn: Tourist Realism in East Africa,” Cultural Anthropology 9:435-70; Chris Rojek and John Urry, Touring Cultures: Transformation of Travel and Theory (London, 1997); and Edward M. Bruner, “Tourism in Ghana: The Representation of Slavery and the Return of the Black Diaspora,” American Anthropologist 98, no. 2 (1996): 290-304.

Acknowledgements:

For generously funding the field research for this project, I would like to acknowledge the following entities at Yale University: the History of Art Department (Lehman Traveling Fellowship), the John F. Enders Research Fellowship, the Pew Program in Religion and American History, and the Center for the Study of Race, Inequality and Politics. For contributing their hospitality, wisdom, and helpful comments, I would like to thank the following individuals: Professor Kellie Jones, Professor Laura Wexler, Kofi Blankson, Paa Kwesi Ocancey, Rosamund H. Arkorful, Grace Amonoo, Sara Asafu Adjaye, Zelda Cheatle, Michael Birt, Nana Ocran, Stephen Korsah, Gina Haney, and Mwenda, Japhiyah and Menefese Kudumu-Clavell. Finally, I would like to offer my deepest appreciation to Robert Forbes, executive coordinator of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition, for recommending me to Common-place.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.4 (July, 2001).

Cheryl Finley writes about photography and African American Art. She is completing her dissertation, entitled “Committed to Memory: The Slave Ship Icon in the Black Atlantic Imagination,” in the departments of African American studies and history of art at Yale University. She is co-author of From Swing to Soul: An Illustrated History of African American Popular Music from 1930 to 1960 (Washington, D.C., 1994) and author of Berenice Abbott (East Rutherford, N.J. 1988). In January 2002, she will join the faculty of Wellesley College.