Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

In 1795, fourteen years after Catalonian and Spanish Franciscans founded Mission San Gabriel, Toypurina, a sorceress who had remained outside the mission system, led the Gabrieleños (as the Spanish came to call the Indian peoples in and near the mission) against the Spanish soldiers and priests. At the inquest after her capture, Toypurina stated that she commanded a chief to attack, “for I hate the padres and all of you, for living here on my native soil . . . for trespassing on the land of my forefathers and despoiling our tribal domains.” The inquest said that Nicolas José, the neophyte within the mission who convinced Toypurina of the necessity of killing the interlopers, desired the extinction of the padres and Corporal Verdugo because they disallowed him his “heathen dances and abuses.” During the night of October 25, 1785, a band of Indians from six local villages entered the compound, but failed in their mission because Toypurina’s special powers failed to kill the padres as planned. Corporal Verdugo of the command discovered the plot; Governor Pedro Fages dispatched in irons the Indian headmen and Nicolas José to the presidio at San Diego and released the others with twenty lashes; and Toypurina suffered banishment to Mission San Carlos in the north.

Events like these shook the missionaries’ faith in the Indians’ ability to fulfill their grand aspiration of communal society based on faith in the One True God. There were usually two soldiers stationed at the mission for protection, but they didn’t make matters easier for the padres. Some soldiers virtuously married Indian women, but the father president of the missions, Junípero Serra, remonstrated to the first governor, Felipe de Neve, in 1780: “We have positive proof that their (the San Gabriel mission Indian) alcalde, Nicolás, was supplying women to as many soldiers as asked for them.” These soldiers carried venereal diseases. The spread of the disease throughout the Indian population produced the physical and spiritual degeneration of the mission neophytes. The situation of “so many sick Indians,” as Padre Zalvidea of San Gabriel put it to the governor in 1832, was no less than utterly tragic. Prefect Mariano Payeras, described the situation in 1819:

The Missions of San Gabriel, San Juan Capistrano, and San Luis Rey have built chapels in their hospitals, in order to administer the sacraments there to the sick more conveniently. I say hospitals, because, as the Fathers observed that the majority of the Indians were dying exceedingly fast from dysentery and the ‘gálico,’ they took energetic steps to arrest the rapid spread of such a pernicious malady by erecting in many of them (missions) said hospitals in proportion to their knowledge and means, and also by procuring such alleviation as was available. In spite of all this, we see with sorrow that the fruit does not correspond to our hopes.

The Spanish priests, moreover, had not figured any way to deal with all the fleas.

It wasn’t just that the soldiers corrupted the priests’ earnest efforts, but the reluctance of the natives to give up their life ways–the fact that they were not blank slates upon which to inscribe the Word of God–doomed the missions. Along the few rivers running through the great basin that would become Los Angeles lived the Tongva, the Shoshonean-speaking, native people. Their largest rancherías–most provided home to fifty to one hundred people–grouped along what the Spanish first called el Río de los Temblores (the River of the Earthquakes), while numerous others lived scattered from the mountains to the sea. To eat they gathered acorns and grasshoppers and snared small animals with superb dexterity. They moved, from the valleys to foothills as the weather suggested, and as they departed they torched their round huts, which inevitably became infested with fleas. They fought a lot too, with each other and with their neighbors, the Chumash, who lived north of Topa-nga, and the Ajachmen to the south. What little we know of these peoples’ lives has come in the form of the artifacts that bulldozers have uncovered in the great metropolis’s implacable building of freeways, houses, and offices.

Almost impossible to exhume is what was most important to them–the Tongva spirit world. One spirit predominated, known as both Chinigchinich and Qua-o-ar, but many smaller spirits, unique to the place, animated the material world and were associated with the weather, animals, plants, and locales. The peoples’ shamans could journey into that spirit world to heal afflictions of the body and soul, but so too could everyday people when they powdered and drank the root of the wicked and transcendent jimson weed.

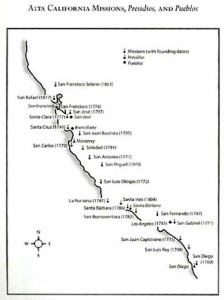

While intrepid Spanish explorers (Juan Cabrillo in 1542 and Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602-03) had audaciously claimed all of Alta California for the Crown, it was not until 1771 that storms that had brewed in far away places would descend on the people of such villages as Yang-na, Cahueg-na, and Asucsag-na. From the College of San Fernando near Mexico City would come priests carrying the Word of that awesome and jealous God first to the natives way to the south, then to the Kumeyaay in 1769 (San Diego), and two years later to the Tongva at the river to which the friars would give the same name as the mission the friars would establish there,San Gabriel. Padre Junípero Serra, the first and most famous of the father presidents of the California missions, brought the Word from Catalan-speaking Mallorca, an island off the coast of Spain. He envisioned that from these people whom he called salvages could be created a most perfect society. Once rid of their devilish heathenism, and compelled–by the whip, if necessary–to confine sex to Christian marriage and labor to European-style farming, the newly Christianized natives would unite as one body in the church: imagine God as the head, the church as the torso, and the newly illuminated believers as the legs and arms, and then how all would be joined via the sacred ritual of Holy Communion.

Father Jose Maria Zalvidea, the outstanding priest at San Gabriel, built San Gabriel into what was called from that time on “the Pride of the Missions.” Father Zalvidea was so earnest a fisherman of souls that he learned the Gabrieleño language and crossed mountains to visit their villages. In a brief diary of 1806 he related one such trip to “the village of Talihuilimit where I baptized 3 old women, the1st of sixty years (and) who had lost the use of one of her legs.” Father Zalvidea had compassion for her and believed in the equality of souls: “To her I gave the name María Magdalena.” The complexity of this priest, though, emerges in the recollection of an Indian, Julio César, who “served him as a chorister.” He told how he “was a very good man, but was . . . very ill . . . He struggled constantly with the devil, whom he accused of threatening him. In order to overcome the devil he constantly flogged himself, wore hair-cloth, drove nails into his feet, and, in short, tormented himself in the cruelest manner.” Such physical penance, understood in part as sharing the Savior’s pain upon the cross, was not uncommon amongst the devout. Padre Serra chastised himself with a whip, too.

While Franciscan priests struggled to Christianize the native people at the San Gabriel mission, a competing idea of civil society–that people could unite through bonds of property, law, and citizenship–came to southern California in the baggage of the first two governors, Felipe de Neve (1775-82) and the former military comandante Pedro Fages (1782-91). These forceful men feuded incessantly with Padre Serra and then the later Franciscan leaders. In part their conflicts derived over who should control the newfound bounty of Alta California and in part over these great ideas of what should organize society and what the future of New Spain (Mexico and the former provinces in the present-day United States) should look like: religious communities or secular, civil towns. To further his conception Neve ordered the founding of two pueblos, one at San Jose in 1777 and the other in 1781 along the Río Porciúncula, where the old village of Yanga-na had been, nuestra Señora de los Angeles. The Mission Road (paved today and tenanted with mostly Asian shopettes) connected the pueblo named for the Queen of the Angels with the mission named for the archangel who bore the good news to Mary that she would bear the Son of God. The rancor would increase between those associated with the vision of a civil and secular Los Angeles and those who would see its future in terms of spiritual utopia.

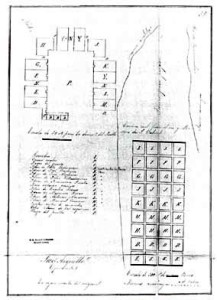

Indeed, it was as if proponents of these two great ideas–of the spiritual and secular societies–had found a barren place where their visions could be played out and the aboriginals’ nondescript existence could be replaced with something sublime. On the side of civil society Governor Neve issued a reglamento in 1779 directing the founding of pueblos (towns). In it he codified the proper ordering of a town regarding house lots, pasturage, a proper plaza, and how “the settlers shall nominate by and from themselves the public officials that shall have been arranged for.” It was with these ideas in mind that Pedro Fages suggested that the area along the Río Porciúncula “offers a hospitable place for some Spanish families to join together as neighbors.” Eleven families who had journeyed from the interior of Mexico marched from the Mission San Gabriel on September 4, 1781, to the site the governor had selected. There are divergent stories of the ceremony which Neve conducted, but we do know that the mission fathers blessed the new pobladores and that they were a mix of mestizos, mulattos, and Indians, though one claimed to be Spanish. With pasturage, cows, and seed they were to be independent economically and politically. Indeed each patriarch described himself in the town records as “queda avezindado en el Pueblo.” Avecindarse means “to join as neighbors,” and this is the word that helps us understand the fundamental social relation in the new pueblo de los Angeles. And there the settlers proceeded to do with the Indians as the rest of Spanish America so famously did–they worked them, corrupted them, and married with them.

In 1784, the Rosas brothers of el pueblo de los Angeles, Carlos and Máximo who were of Indian and mulatto descent, both married gentile Indian women (who had to be baptized for the occasion.) The two women of Yanga-na and Jajambit rancheras were both probably familiar with pueblo life. In 1796 another Rosas married a neophyte from San Gabriel, as had a number of other pobladores. Those few soldiers from Santa Barbara and San Juan Capistrano who married Indian women, as Spanish policy encouraged, mostly moved to Los Angeles before the turn of the century. After forty years of missionization, a very few Indians were selected to leave, marry other “nuevos cristianos,” and join the pueblo.

On and on went the diatribes of the friars about “the residents [who] are a group of laggards . . . in those pueblos without priests.” Imagine the righteous indignation when Dona Eulalia Callis, the wife of the archenemy of the missions, Governor Pedro Fages, furiously and publicly sued her husband for divorce, charging in 1785 “that I found my husband physically on top of one his servants, a Yuma Indian girl,” an event known to have been common for the governor, pobladores, and soldiers. As Padre Zalvidea fumed from San Gabriel about Los Angeles in 1816, “That [pursuit] to which everyone dedicates himself is to go about on horseback, put in grapevines, hiring a few gentiles for this purpose, teach them to get drunk, and then take jars of aguardiente [“firewater” or brandy] to Christian Indians.”

We see emerging in Los Angeles what happened to so many Indians who did not die or whom Europeanization did not sweep into the dustbin of history. They became Mexican culture. Their children would be essentially Hispano-Americano, neither Indian nor Iberian in culture but a hybrid, a mestizo. This was the great idea that, out of the wreckage of Spanish imperialism to which the Catholic Church had attached itself, came from the variously sanctified and base mixings of the Americas: the stunning idea that people were not one thing or the other, nor even some cross between two civilizations, but some new mestizaje, some new way of being altogether. This mixture has been one of the great tensions–sometimes creative, sometimes confusing–in Los Angeles and the other great Latin American cities of the New World.

This now-great metropolitan center of Los Angeles has its genesis in the religious and the civil, the sacred and the profane, but its growth and troubles and strengths have been about the issues associated with mixing. In this place where God and Church once dictated authority in the mission and Holy Communion bound neophyte and Christian together, where neighbors (vecinos) had voluntarily entered into a civil arrangement in the cause of settling the place for the Crown and for production of subsistence, there has been at once conflict and accommodation, and separation and mixing. Thus it was that along one river did the vision of a society united by the One True God in the Mission San Gabriel contend with the town only a few leagues distant along another river, one motivated by the vision of an enlightened civil society. Some readers might want to know that, while the two rivers flow separately to the sea, the two places quickly and unalterably mixed into a world famous city, the very one that arguably portends our urban future.

Further Reading: Because Los Angeles history has always been so fractious–a historiography that reflects the controversies over its founding within the Spanish Empire–the secondary sources are stunningly varied in their points of view, choices of documents, and agendas. Pro-church scholars have blamed Fages and the soldiers for the failure of the missions and the iniquity at the pueblos. Others, often for genealogical purposes, have celebrated the first “pioneers.” More recently, scholars have emphasized the victimization of the Indians by the soldiers, settlers, and the church. I will somewhat ungraciously suggest my own book, Thrown among Strangers: The Making of Mexican Culture in Frontier California (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1991), for a more balanced view of the Mission San Gabriel and the founding and evolution of Los Angeles, and enthusiastically recommend the wonderful collection of documents that Rose Marie Beebe and Robert Sankewicz have edited, Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535-1846 (Berkeley, 2001). Each has a strong bibliography.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Douglas Monroy is professor of history at The Colorado College and the author of Thrown among Strangers: The Making of Mexican Culture in Frontier California (Berkeley, 1990), and Rebirth: Mexican Los Angeles from the Great Migration to the Great Depression (Berkeley, 1999), both from the University of California Press. He is presently finishing a book called In the Footsteps of Father Serra: Essays on California, Mexico, and America.