Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

In August of 1889, eighteen-year-old Caroline Meeber boarded the afternoon train that would take her the hundred miles or so from her home in the small Wisconsin town of Columbia City to Chicago. Her plan was to live at least for a while in the modest flat of her married sister Minnie Hanson and find a job. Minnie had proposed this arrangement not because she missed her sister, but because Carrie was “dissatisfied” at home, and the frugal Hansons could use the money Carrie would pay for her board. The expectation was that Carrie “would do well enough until–well, until something happened . . . Things would go on, though, in a dim kind of way until the better thing would eventuate and Carrie would be rewarded for coming and toiling in the city.”

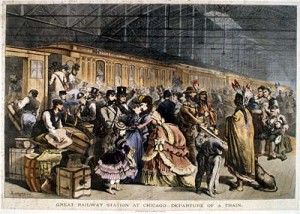

This particular journey never actually took place, except in the opening pages of Theodore Dreiser’s first and best novel, Sister Carrie. Still, it happened for real hundreds of thousands of times, and Carrie Meeber’s short but momentous trip captures the essence of life during Chicago’s formative years. The salient fact about Chicago’s early history is the city’s explosive growth, thanks to its location at the western edge of the Great Lakes when the full force of unrestricted industrial capitalism took hold in America. No other city in the nation grew so much and so fast. Chicago was a metropolis created out of nowhere and everywhere in a historical instant. While the region where Chicago is located was explored by Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette in the 1670s, as late as 1830 it was still an isolated outpost with a smattering of settlers. But between Chicago’s incorporation in 1837 and Sister Carrie’s publication in 1900–barely two generations–the population rose from 4,170 people gathered near a weedy portage site to just under 1,700,000. According to the census of 1890, conducted the year after Carrie’s fictive arrival, over 41 percent of Chicagoans had been born abroad, with more than half of these immigrants from Germany or Ireland. A third of the native-born residents were, like Carrie, from a state other than Illinois, an even larger portion from outside Chicago itself. Near the beginning of The Cliff-Dwellers, the novel published in the early 1890s by Henry Blake Fuller (who was, against the odds, actually from Chicago), a recent arrival from Boston asks, “Is there anybody in this town who hasn’t come from somewhere else, or who has been here more than a year or two?” Virtually all of the newcomers, and the equally staggering number of people just passing through, came into Chicago on the train

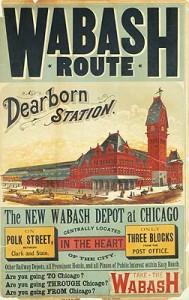

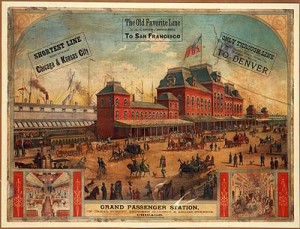

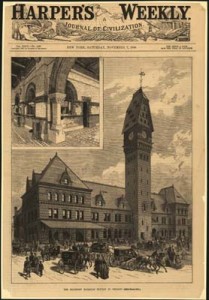

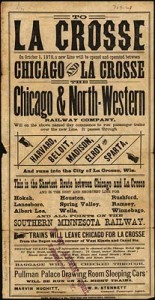

Chicago was originally a river, lake, and canal town, but since the Civil War it had been what transportation historian George Rogers Taylor calls “the greatest railroad city in the world.” The level landscape that surrounded it for miles may have lacked stunning beauty, but it helped make Chicago the ultimate railroad nexus, the place, as Carl Sandburg put it, “where all the trains ran.” These trains carried not only people, but also massive amounts of grain, meat, lumber, and other commodities, as well as a rapidly expanding volume of manufactured goods, establishing Chicago as the country’s great inland mercantile and industrial metropolis. By 1890 only New York was larger. In a city increasingly characterized by class and ethnic distinctions, the trip in by train was arguably the one significant personal experience that more Chicagoans had in common than any other. It is no surprise, then, that descriptions of the entry into Chicago on the train appear repeatedly in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century fiction and memoirs of life in the city, not to mention many visitors’ accounts. Master financier Frank Cowperwood, the protagonist of Dreiser’s The Titan, intuitively follows the money from the East Coast to Chicago along the tracks that also carry the unskilled laborer Jurgis Rudkus and his family on the last leg of their long trip from Lithuania to the hell-on-earth that is the stockyards in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. Architect Louis Sullivan and Haymarket anarchist Albert Parsons, both persuaded by the panic of 1873 to pick up stakes in Philadelphia and try their luck amidst the prospects of Chicago, arrived at virtually the identical time to begin their very different careers. Frank Lloyd Wright was scarcely a year older than Sister Carrie when in 1887 he took the same journey she did from Wisconsin to Chicago.

Each of these immigrants and virtually all of their fellow passengers left home with the same expectation that Carrie had, that Chicago offered richer opportunities than where they had been. Most did not come for religious freedom, to establish a colony, or for education and refinement, but to try their skill and luck as free agents, or so at least they thought, in the irresistibly powerful laissez-faire economy of which Chicago, for better and for worse, was the leading edge. “This town of ours labors under one peculiar disadvantage,” a reflective Chicagoan observes with resignation in another Fuller novel, With the Procession–,“it is the only great city in the world to which all its citizens have come for the one common, avowed object of making money.” This remark doesn’t quite have it right. True, virtually all of Chicago’s newcomers were, like Carrie, seeking a better life where “better” was defined substantially in material terms, but what attracted them perhaps as much as money was the idea of constant change that Chicago represented. Chicago could integrate even a disastrous fire into its all-consuming booster faith because it was already accustomed to being continuously remade. Chicago is “always a novelty,” Mark Twain commented with admiration, “for she is never the Chicago you saw when you passed through the last time.” It was the place to go–a “magnet attracting,” in Dreiser’s words–because it was the preeminent locus of what Saul Bellow has called “the transforming power of the modern,” a power whose creative and destructive tendencies, as Marx pointed out, are inseparable from one another. Chicago was, on one hand, the birthplace of modern commercial architecture, the possessor of a vibrant cultural life that drew all kind of artistic spirits (including Dreiser) and of a well-heeled civic pride that erected museums, concert halls, and universities and mounted the World’s Columbian Exposition. On the other, it was the site of the Haymarket bombing, the most sensational and divisive act of urban violence in an era of terrible social tensions, and of the Pullman Strike, the most famous and far-reaching labor conflict of its time.

Whatever the motives that put all these people on the railroad to Chicago, it is the qualitative feel of the entrance on the train that embodies the essence of life in the city during the late nineteenth century. In account after account, the journey in seems to recapitulate before the traveler’s eyes the nation’s rapid transition from rural to urban. “The complex quality of this wonderful city,” University of Chicago professor (and recent exile from Harvard and Cambridge) Robert Herrick wrote with considerable irony in 1898, “is best seen as the stranger shoots across the prairie in a railroad train, penetrating layer after layer of the folds.” As the train approached Chicago, its riders witnessed farmland giving way to houses and to what Dreiser called, in his autobiographical account of his own trip from his native Indiana a few years before Carrie’s, the “sudden smudge” of factories amidst the “great green plains.” Next came the increasingly tight network of railroad tracks and telegraph wires through which one finally penetrated the entirely manmade landscape that was the city’s heart. That this history of American urbanization is displayed to the passenger both by and from the train–the literal engine of nineteenth-century mechanization–makes it all the more vivid and intense. In a city that seemed itself to be always on the move, how better to view this place than while in motion, conveyed into its center by the essential agent of change? Like the direction and velocity of life in Chicago, however, the train was outside the control of the individual rider, who was pulled by the anonymous locomotive up ahead. Perched in a passenger car entering Chicago, one was somehow of the city that the train had created but separated from it, coursing through all the activity while sitting still, driving yet driven. The responses this entry engendered anticipated the paradoxical state of mind and body, once one was settled in the city, of feeling empowered at being part of the Chicago colossus while being powerless to shape experience within it. Although the descriptions of Chicago as one enters on the train are remarkably similar in the details they note, the reactions of the travelers greatly diverge. For some, the first arrival was nothing short of inspirational. Sullivan, who was drawn to Chicago by the promise of new architectural work demanded by the fire, recalled decades later that he “tramped the platform, stopped, looked toward the city, ruins around him; looked at the sky; and as one alone, stamped his foot, raised his hand, and cried in full voice: THIS IS THE PLACE FOR ME.” Writing in his autobiography, Dreiser similarly remembered that stepping out of the train as a teenager into “the hurly-burly” of Chicago made him feel “as though I were ready to conquer the world.” Herrick, in contrast, called the “huge spider’s web” of railroad lines “a stupendous blasphemy against nature.” Once within the city, Herrick advised, “the heart must forget that the earth is beautiful.”

No one captured the new arrival’s entrance by train as well as Dreiser did in Sister Carrie. His heroine is “bright, timid, and full of the illusions of ignorance and youth,” an apt representative for so many other newcomers. Her most important assets are not the contents of her cheap imitation alligator-skin satchel nor the four dollars in her yellow leather snap purse (a whole week’s pay, she soon discovers to her dismay, for an untrained factory worker), but her youth and good looks, her ambition and energy, and her desire to escape the limited round of life in Columbia City and embrace the open-ended possibilities of Chicago. There’s a gush of tears as she kisses her mother goodbye, a touch in her throat when she takes a parting look at the flour mill where her father works, and then a “pathetic sigh as the familiar green environs of the village passed in review.” These personal ties have little power compared to the draw of Chicago, however. “Since infancy,” Dreiser explains, “her ears had been full of its fame.” As the train pulls away from Columbia City, we’re told, “the threads which bound her so lightly to girlhood and home were irretrievably broken.” We know that this is an irreversible one-way journey of both Carrie and the nation into the American urban future. Indeed, almost immediately Carrie’s thoughts turn to “vague conjectures of what Chicago might be.” Carrie is eager for pleasure and comfort, and Chicago, like her still only partially formed, is in her mind the correlative of all her hopes. “A half-equipped little knight she was,” Dreiser writes, “venturing to reconnoiter the mysterious city and dreaming wild dreams of some vague-far-off supremacy which should make it prey and subject, the proper penitent, groveling at a woman’s slipper.” As she daydreams out the window at the passing landscape, Carrie hears “a voice in her ear.” The voice belongs to Charles Drouet, the charming masher who will seduce her not long after her move to Chicago but whom Carrie will soon outgrow as her own personality develops through her contact with the dynamism of the city.

Their meeting in the cars is entirely fitting because Drouet is a creation of the city and the train, a traveling drummer for a leading Chicago dry-goods house. His tight-fitting and perfectly coordinated clothes, his smooth conversation, his ease of manner, and his mastery of the situation constitute Carrie’s initiation into urban style. Drouet’s “shiny tan shoes, the smart new suit and the air with which he did things built up for her a dim world of fortune around him of which he was the centre,” Dreiser notes. “It disposed her pleasantly toward all he might do.” In a matter of minutes he has assumed the seat beside her, and they are exchanging familiarities in a way that could never happen in Carrie’s safe and boring home town. All this seems completely natural on the train to Chicago, which is an extension of the city as an accidental place full of uprooted and unattached strangers whose lives become unexpectedly intertwined. Drouet’s friendly assurance and flattering attentions put Carrie at her ease, even though she is at first as anxious as pleased at his interest in her. Soon she has surrendered to him the address of her sister, and they have agreed to see each other the following Monday evening. Dreiser then switches attention back to the view through the car window as the train nears Chicago. They pass “lines of telegraph poles stalking across the fields,” “smoke stacks towering high in the air,” and “two-story frame houses standing out in the open fields, without fence or trees, outposts of the approaching army of homes.” Drouet, Carrie’s self-appointed guide to the city he personifies for her, points out landmarks and informs Carrie that Chicago is nothing short of “a wonder.” But she barely hears him, since now her heart is “troubled by a kind of terror.” It is the terror that so many others must have felt when, like Carrie, they suddenly realized that they were “alone, away from home, rushing into a great sea of life and endeavor” in Chicago on the train. Her pulse beats rapidly, she is choked for breath, she feels ill. Once they are in the station, Carrie has recovered sufficiently to decline Drouet’s offer to carry her luggage, since she does not want her sister Minnie, who is meeting her, to see him. Having watched longingly as Drouet disappeared into the crowd and now walking alongside Minnie into her new life, Carrie feels “much alone, a lone figure in a tossing, thoughtless sea.” She has been exhausted and disoriented not by her short afternoon’s trip in time and distance on the train to Chicago, but by the much longer, more arduous, and wholly unanticipated psychic journey she has made through extremes of powerful inarticulate feeling. This lonely, tossing, thoughtless sea in which Carrie is swimming as she concludes her entrance into Chicago is Dreiser’s metaphor for what the German sociologist Georg Simmel identified shortly after the publication of Sister Carrie as “the mental life of the metropolis,” which, Simmel contended, derives from “the intensification of emotional life due to the swift and continuous shift of external and internal stimuli.” Simmel might have been describing the state in which Carrie repeatedly finds herself through the rest of her urban career, during the course of which her mood shifts again and again between exhilaration and ennui, expectation and disappointment, hope and fear, confidence and confusion. The overture to that career, full of the swift and continuous shift of external stimuli so familiar to her and other Chicagoans, is her journey into the city on the train.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4

Carl Smith is Franklyn Bliss Snyder Professor of English and American Studies and professor of history at Northwestern University. He is author of several articles and books on nineteenth-century Chicago and curator of the online exhibitions The Great Chicago Fire and the Web of Memory and The Dramas of Haymarket.