I sat the early night under watchful care of guardswomen—Lilly (who wants to be Dawn), her small girl Mary (who will become Iona) and Eve (who will stay Eve in this life, one-eye a weary cloud and one on my unveiled head)—all huddled in our dirt shed, waiting to be discovered. The night cut from both ends gave us little time for breathing, less for tracing the route in my hair. They use wool card, water and seed oil to fashion a plat. Plotting the straight and winding way, a comb made from bits of bone burns my scalp. Eve sees the route, sometimes with her good eye closed, and I was born brave—surly and wry white folks say, meaning, I must be watched for all my wandering into the wrong row, the lash, anywhere almost a country, a reckoning of its own. I am almost born a bird, say these women who saw me landed here, almost a comet—wild-eyed, strands streaked with gray, face ageless. I leave tonight with all the makings of an unknown journey. I run for a doorway, river, hearth, cave with a ladder. If I am caught, what body will return? My crown, they’ll loose me of it. If I am dragged back, they’ll burn lie into my skin. In heaven, I’ll have my body. Wade past what freedom they know. This furrow of want and the root in my hair—the patience of the wild—guiding me. The guards make me repeat what comes before the map: trace black moss along swamp’s edge, find the stone mile post at the base of the water where dying trees bend and lean. Sabbath Eve. Nothing on the path but stands of angels, also hiding, before the deep tract of living. Scarf perfectly black as skin and thin to keep the map from unraveling. Years from now, remembering this, it will seem like a dream—brief sleep in the hollow of a tree, my palm: a lover reading my hair. I am all creation: bark and mud and silver, the matter surrounding stars, undershine and crown, fire-fly wing and inlet, the dark in God’s mouth, silent altar, prayer flesh.

Lost Friends.

NOTE. –We receive many letters asking about

lost friends. All such letters will be published in

this column from the end of the Civil War until

those in need stop looking and, in such a case, in

perpetuity. We make no charge for publishing

these letters from subscribers to the Southeastern

Herald. All others enclose fifty cents to pay for

publishing. Pastors will please read the requests

published below from their pulpits, and report any

case where friends are brought together by means

of letters.

___________________________

Dear Editor: I wish to inquire for the women

in me, in the interest of my mother, father,

aunts, uncles and a great many cousins.—I want

to find my people. They were carried from us

when I was less than thought of. In their

dreams, they called me Seborn or Glory but

now I am called Still Becoming. My parents’

names are Here, Holding. Uncles names are

Sprightly, Long Gone, Whisper and Roadbed;

Aunts Hunger, Childfree, Childmany, Want

and Wanting. My cousins are like blades

of grass or kudzu and can barely be chased or

named. Some were here, some are dead.

Before the war, these women belonged to

Masters most of us have swallowed but each

eve return as odd growths under the skin. My

mother’s mother and father’s grandmother’s

grandmother were barely living in Petersburg,

Va. There were within miles of each other

and, I fear, did not know blood was nearby.

We heard tell before then one was bought by a

family named Gee or Blackburn, the other by

some called Hyman or Knight; they died and

we fell to others. I was born and have not

heard from them since. Friends, if you have

footing on their whereabouts, please Address

me at Stillwater, Va., with letters, trinkets, any

knowledge of what’s come of us.

Poetic Research Statement

In July, my husband and I take our children to the new National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. It has taken six months to get tickets and the lines outside and in are still wrapped around the structure, the makeshift ropes, the Slavery and Freedom 1400-1877 exhibits. What is left to say about slavery? a woman asks loudly, her irritation palpable, as we make our way in. Before the trip, I’ve begun working on a project about my grandmothers that’s been swirling in my head for years. In a strange twist of kismet, my ancestors intersect in Petersburg, Virginia, forty years before I am born. My paternal great-great-great grandmother, Minnie Fulkes, lives in Petersburg and is interviewed for the WPA slave narratives in 1937. My maternal grandmother, Mary Knight, after birthing her first child, is given a diagnosis of “water on the brain” (post-partum was an ongoing mystery) and sent to the Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane in 1940, a stone’s throw from where Minnie resides. I find this connection fascinating—two disparate women of my history, at opposite ends of their lives, converging upon the same space and time, telling their stories and ushering in the stretchstrain of folks who will usher in me. I know their lives commence long before this confluence and am determined to search for their beginnings.

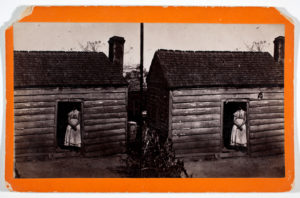

I am a poet, so I must call on history’s gatekeepers (librarians and elders) to help me. They send a confluence of archives and databases, marriage and birth certificates, books and burial plots. My inquest becomes part ethnographic, part family lore. It is difficult for most Black Americans to trace ancestors past 1865, as it is for me, so I begin looking for little-known cultural and regional history to fill in the minutia of the times. Research is often what feeds me as a poet and I am prone to follow tangents until I am given a spark. I have traced invented psychoses, living quarters, grooming and hair rituals, faith practices and maroons before my family and I arrive on the museum’s bottom floor. I pride myself on being staunch, matter-of-fact, clear, and considered when teaching my children about even the ugliness of history. I am only teacher-mother-knower explaining artifacts from a slave ship. Teacher-mother-knower near Jefferson’s ancestors, stacked as a pile of engraved bricks called the Paradox of Liberty. I turn a corner when a reconstructed slave cabin stands in front of me. I have been reading the book Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation by John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger and recognize the cabin’s slatted wood, dark entry, and dirt floor. I am mother-daughter-brokenbird, and cry in the museum’s corridor.

In early America, I am searching for what my ancestors may have seen and known. I have no illusions about finding things they might have loved because what was to love about being Black in America other than being alive? I am looking for their daily things, their living, evidence that they marked this land, were more than marked by it. I am trying to picture the physical space, so begin researching antebellum Virginia landscapes and battlefields leveled by hard-fought progress. What was bound in the trees then? I read Daniel O. Sayers’ book A Desolate Place for a Defiant People: The Archeology of Maroons, Indigenous Americans, and Enslaved Laborers in the Great Dismal Swamp at the same time I am combing through ads from The Geography of Slavery in Virginia, a digital repository of runaway slave advertisements and other documents from 1736-1803 helmed by the University of Virginia. While most who placed the ads believed the enslaved were running for cities or ports nearby, Sayers’ text presents a new idea for me: thousands of runaways made their way deep into the Dismal Swamp, where they created communities and lived in freedom, most never emerging until after the Civil War. Just past the cabin at the museum, I photograph objects from a Spirit Bundle, a collection of amulets that mirrors West African traditions meant to protect passageways between physical and spiritual worlds. Because there are so many people and so little time, we have to move quickly; Reconstruction is a blur and soon we are three floors up in the modern-day galleries. I am arrested by a large visual artwork, a crown of sorts made of tools used to sculpt Black hair about which the artist, Kenya Robinson, says on the object label: “For complex reasons of race, class, gender…I will probably have a hair conversation with other black women for all of my days, like some kind of not-so-secret handshake of experience and history.” I begin writing the poem “Commemorative Headdress For Her Journey Beyond Heaven” with all of these seemingly disparate encounters swirling in my mind. I imagine a woman who is having the route she must travel to escape the plantation braided into her hair. (I haven’t found evidence of this tactic being used in the U.S.; this is just hope and imagining—though I am fascinated by the legacy of Colombia’s Benkos Biho, as braiding maps into the hair of women has been reported as a method used to help others escape). The poem’s speaker is looking for a pathway into another world, here the swampland that will put her and her sistren out of reach, sight, and mind. Writing the poem I think again about what the enslaved loved, the bundle and amulets. Of course they loved even the thought of freedom, the hope and wonder of it, of being together in it, a Black kind of heaven. Hence, the title of the poem is the same as that of the visual work by Robinson, with the exception of one article (from changed to for), as the poem is meant to convey the beginning of a journey and not an ending of or looking back on one.

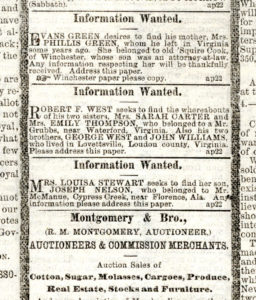

When we leave the museum, I look for things I’ve missed. Weeks later, I find a picture on my phone of thousands of well-dressed Blacks lining the streets of an unknown city with the caption “Emancipation Day Parade, 1905” and can’t remember when I took it or what was nearby, so I scour historical newspapers like the National Anti-Slavery Standard and the Norfolk Journal and Guide from the 1840s through the 1950s. What I find is a great many people searching—for good omens, legal victories, justice, faith, children, joy. The “Information Wanted” and eventually the “Lost Friends” columns, published as early as 1866, filled full pages of each standard. Freed men and women placed the advertisements to search for others lost before or during the war. In her book Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery, Heather Andrea Williams does the seemingly impossible work of following the trail of these ads, their impetus and a few outcomes. The Historic New Orleans Collection, much like The Geography of Slavery in Virginia, has digitized thousands of the columns. After reading fifty or so, I come across one by Maria Ross of Yazoo City, Mississippi, published in the Southwestern Christian Advocate that began, “Dear Editor:—I want to find my people.” And it breaks me open inside. It is so plain, please help me find my people. It cuts me to the core remembering that all folks wanted was to be together, to have someone to love and find anyone who knew to love them. The weight of my grandmothers—with all their fullness and distance—wearies and worries me. I write the poem “Lost Friends.” as an imitation of the column but with modern-day connotations of those left wanting by their absence. There is pleading, because I am desperately searching, there is birthing and blood and loss, there are figurative names that tell our stories juxtaposed against family monikers that most likely belonged to the slaveholders we are ever trying to cast off. Something about sifting through pieces of the once-living lends itself, in my brain, to various types of abstraction. I know no matter how many details I uncover, there is still a breathing wanting left out of all I’ll find. The poet’s job (i.e. the poet as historian, as opposed to other undertakings such as poet as soothsayer, poet as family arbiter, poet as line dancer and the like) is to make the dead become the living. I hope these poems, and all the summer’s discovery, will eventually become a larger body of work, a book of poems in the voices of those journeywomen illumining the voices of the times they endured. Perhaps, for someone in the distance, the poems will blossom and be: a Spirit Bundle, a trove or pathway, what there is left to say, an alternate kind of history.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4.5 (Fall, 2017).

Remica L. Bingham-Risher earned an MFA from Bennington College, and is a Cave Canem fellow and an Affrilachian poet. She is the author of three books: Conversion (2007), What We Ask of Flesh (2013) and Starlight & Error (2017). She is the director of Quality Enhancement Plan Initiatives at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.