Author’s Note:

As I hope will become readily apparent, The Hungry Eye is a work of historical fiction. Some of its characters and incidents are pulled from the historical record–most particularly, the dueling “special artists” Peleg Padlin and Little Waddley. Their misadventures while touring New York’s netherworld originally appeared in an 1857-58 series of articles in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper written by New York Tribune reporter Mortimer Neal Thompson. That the pseudonymous pictorial reporters stood in for Leslie’s staff artists Sol Eytinge Jr. and a very young Thomas Nast should not be of concern to the present-day reader. Moreover, the mystery at the heart of The Hungry Eye, which entangles these and other characters and the constellation of their relationships, is my own invention. Much of what transpires here (and in the ensuing installments, which will appear in Common-place monthly between January and April) is utterly fantastic–and yet it also, I believe, remains true to the history of a specific time and place.

While I originally conceived of The Hungry Eye as a conventional novel (at least in the sense that it would end up as a tactile book printed on paper with a spine available for cracking) the chance to emulate the once ubiquitous format of serialization was hard to pass up. And wedding an older episodic approach to the still inchoate medium of the World Wide Web offered an intriguing narrative challenge. Aside from requiring some reconfiguring of the story’s structure to accommodate the start-and-stop pacing of extended and intermittent reading, I’ve tried to work with the Web to intermingle the visualization of the past–which plays a prominent role in the plot–with the telling of the story. That said, you won’t come across any state of the art programming here: what I’ve tried to do is enhance the reading experience on the Web, not replace it.

All original artwork © 2001 Joshua Brown.

The increase of vice and rowdyism among the youth of our cities is in a great measure to be attributed to the decline of the apprenticeship system. When that system was general, masters had some control over their boys; they were obliged to keep them out of vice as much as possible, and they had personal interests in their conduct . . . [Now the] master does not wish the trouble of providing for all the wants of the boy, and the latter desires independence of control when not actually at work.

–“The Modern Apprenticeship System,”

Fincher’s Trades’ Review, November 14, 1863I cannot understand the mystery: but I am always

conscious of myself as two (as my soul and I).–Walt Whitman

This is hell, this is hell

I am sorry to tell you

It never gets better or worse

But you’ll get used to it after a spell

For heaven is hell in reverse–Elvis Costello

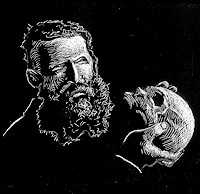

Nondescript

Pity the poor sketch artist who can render one subject with skill but is incapacitated in pursuit of another.

Peleg Padlin was not particularly articulate. You wouldn’t go to him for a mellifluously phrased description of an event, personage, or place, let alone a disquisition on the slavery question. He was, after all, a Frank Leslie’s Special Artist, not one of the weekly newspaper’s wordsmiths. What he failed to enunciate in words he could, with relative ease, miraculously transmogrify into form: when it came to providing context–the corruption in a close Five Points hovel; the crush of horses, omnibuses, and drays on Broadway; the thrash and roil of a sky heavy with rain over the Battery–no one on the staff could hold a candle to him.

Yes, Padlin excelled as a draughtsman. But there was one thing he could neither articulate nor sketch. And, unfortunately, it was a fairly ubiquitous item in the artist’s repertoire: faces. Padlin could not capture a face. Understand, Padlin could draw a face; he had no problem handling the basic anatomical structure or constituent features. But, try as he might–and Padlin tried mightily–specific, even vaguely accurate, likenesses utterly evaded his grasp.

Few actually remarked on Padlin’s dilemma, though over the course of repeated failures it became general knowledge in the newspaper office. How many times had Padlin’s botched efforts been redone by Little Waddley? What was more often the subject of comment was the effect of Padlin’s incapacity on his temperament: his was a dark, brooding, irreproachable presence. Among his colleagues were some of a more empathic bent who, upon the summoning of Little Waddley, would have pitied Padlin–if the draughtsman’s mortification had not taken such an ominous turn. In the dichotomous parlance of the day, Peleg Padlin’s personality decidedly favored shadows over sun, gaslight over daylight. With his mouth clamped tight like the vise in a blacksmith’s shop, and with his beaver hat pulled low over his brow to hide the consternation that racked his features, Padlin gained a reputation in the illustrated weekly’s office for misanthropy if not downright meanness.

“The visitors to the morgue didn’t want to know about the histories of these victims of horse-car accidents, domestic strife, or disease. They came for one purpose and one purpose only: to be assured that they would not suffer the same fate as these unfortunates.”

At the moment, Padlin’s air of restrained wrath seemed appropriate.

His scowling countenance, his head bobbing up and down from subject to paper, subject to paper, his hand moving agitatedly upon the pad’s surface, conveyed a revulsion barely kept at bay. At least, that was John Antrobus’s interpretation when he entered the viewing room and espied the sketch artist crouched amid the marble slabs.

When the young coroner’s deputy saw what he took to be distaste creasing Padlin’s features, a heavy gob of emotion slid up his gullet. Suppressing a shudder, he nonetheless felt wonderfully relieved. His own horror at Padlin’s horror had been a reawakening of the grief that he thought irretrievable after this long first month of escorting every cholera fanatic and Tammany slug in the city on tours of the new morgue. A month of so many hushed “ohs” and “ahs,” so many seemly silences betrayed by popping eyes, so many genteel applications of kerchiefs to flared nostrils, so many semi-swoons with crinoline gowns crackling concentrically up against the tile floor–so much civil distress expressed by types for whom grotesque death was the stuff of Barnum’s Museum and not the sordid experience of the streets.

Antrobus’s job, as his superior instructed him, was to reassure the populace. The visitors to the morgue didn’t want to know about the histories of these victims of horse-car accidents, domestic strife, or disease. They came for one purpose and one purpose only: to be assured that they would not suffer the same fate as these unfortunates. They came to visit the new structure along the East River like picnickers viewing a battlefield from the safety of a ridge or bunker, to witness death close at hand while remaining secure that they were shielded from its effect.

The trouble was that Antrobus had chosen this unorthodox calling for the express purpose of notreassuring the respectable classes. Having conscientiously mapped the landscape of corruption and misery during his years at the Yale Medical College, upon graduation he had packed a nightshirt, several hard collars, and his Bible in a carpetbag, filled his stiff leather satchel with instruments and pills and elixirs, and carried them, along with his new expertise and spiritual mission, to the slums of New York’s Five Points. For a year, he ministered to the poor from the House of Industry (replacing the Reverend R_____, who had succumbed to the area’s melancholy and mania, leaving his post a hopeless inebriate).

For a year, Antrobus supervised the sewing work of those few wretched women who entered the missionhouse for employment; he cajoled and purchased the meager attendance of neighborhood children at his Sabbath classes; he inspected the hovels surrounding Paradise Park to uncover cholera nests; he withstood the howling threats of the Papist gangs that soared through his window every night. And to what end? To watch the contributions from uptown sponsors recede to a trickle and the Points inhabitants grow more and more surly and resistant to his good works? He prayed for guidance–and, finally, his prayers were answered by a revelation. Albeit a peculiar one.

One dark night–dark only in the hopelessness of the moment, for the illumination from the taunting Mulberry Street Boys’ torches played upon his bedroom wall from dusk to dawn–one long, sleepless night, young Antrobus suddenly realized that if he was failing to arrest the terrible fates of his putative flock it was possibly due to a kind of directional confusion. What if he forsook the lives of the deserving and undeserving poor and took a reverse course? What if he started with death and worked backwards, exposing the gruesome lessons of the corpse to enlighten the uncaring, exploiting fear of infection to wrest the attention of patrons?

No, reassurance had not been Antrobus’s goal when he won the position of coroner’s deputy. Instruction, life lessons, death lessons: these were closer to what Antrobus had in mind. The coroner, however, was a pragmatic man who maintained his post through connections with Tammany Hall and had no use for missionary zeal. So, torn between countering the coroner’s aim and keeping his job, Antrobus opted for a wary vigilance, searching for an opportunity to further his mission, hoping for another revelation. In the meantime, he steeled his emotions to the task at hand.

And here now, before him, crouched the possible agent of his deliverance.

“‘For the love of God, Padlin, all your damned people look the same! They alwayslook the same!'”

Padlin enjoyed drawing animals–largely because they did not require the particularity of the human visage. If two pigs looked alike his editor wasn’t going to complain about it. And Quidroon complained plenty about Padlin’s people.

“What we seem to have here,” Quidroon would say at the start of a typical critique, Padlin having laid a sketch before him, “is a medical phenomenon.”

Padlin, of course, would admit nothing.

Quidroon would then embark on a more intense survey, his head moving over the drawing in a manner that reminded Padlin of a rodent exploring the possibilities scattered over a kitchen floor. “Quite a spectacle,” Quidroon would murmur. “Astounding. Astonishing.”

Padlin would remain mute, although his eyes (strategically obscured in the gloom cast by the brim of his perpetually donned hat) trembled violently in their sockets.

“How shall we caption this sketch, Mr. Padlin?” Quidroon would finally ask as his head ceased its meandering scan. “Would ‘The Grand Mili-tuplet Convention’ be an appropriate title?”

Padlin had no penchant for neologisms, not that he would give Quidroon the satisfaction of saying he failed to get the joke. The editor’s meaning was clear enough. So Padlin stood there, his rage beginning its inevitable descent toward resignation as this ritual lurched toward its familiar outcome.

Meanwhile, his stab at malicious, if arcane, wit having been blunted against Padlin’s obtuse silence, Quidroon would then expend a number of sighs while patting the top of his head. The effect, from Padlin’s vantage point, was not unlike watching someone trying to stamp out a spreading brush fire–although there was little enough to burn on Quidroon’s bald pate. The conflagration, however, was gathering force within that naked and reddening skull. Sometimes Quidroon would patter and sigh for seconds, sometimes for minutes. Eventually, the flames burst forth:

“Are you following my drift, Mr. Padlin?” Quidroon would suddenly shout. “Do you understand what I’m saying?”

Quidroon would finally glance up at the Special Artist’s somber face. “For the love of God, Padlin, all your damned people look the same! They always look the same!”

And with that, Quidroon would summon, in a stentorian voice, Little Waddley. As his diminutive colleague made his entrance (having stood ready in the wings, awaiting his superior’s call), Padlin would turn away, never sure of his ability to withstand the sight of his sketch kidnapped once again. Outwardly, Padlin continued to exhibit his indiscriminate scowl, maintaining the expression into which his face had configured as soon as he’d entered the newspaper’s offices. But, as he walked away to the discordant music of Quidroon and Waddley’s conspiratorial prattle, Padlin burrowed into the nether reaches of his mind, his vision blurred in a viscous cloud of shame and helplessness.

|

“The sketches were gruesome, wonderful.” |

Subjects

Things were going well for Padlin in the morgue. He scanned his work with satisfaction. The dankness of the dreadful place, a clamminess pierced by dagger thrusts of disinfectant, the loneliness of the sound made by his pencil on the rough paper–the terrible, stark atmosphere of the place had transferred perfectly from his psyche into his hand. Every one of his pencil strokes struck home.

The sketches were gruesome, wonderful. He’d got the light just so, the murky illumination of the gas jets above the slabs. The geography of the room was accurate, and he’d captured the inert solidity of the dark walls bearing down upon the viewer, as well as the ghastly impression of the water jets extending from the ceiling like a row of spiders spewing foggy webs. Padlin’s lines were all efficiently placed, the shading exact. He was quite pleased with himself, and the confidence did not flag as he moved from sketch to sketch. It was only due to force of habit that discontent remained on his face.

And then this pale, starched clerk appeared to ruin everything.

“May I be of help?”

Padlin, crouched over his pad, twisted around awkwardly. A man, dressed in black, stared down at him. The blackness appeared to have migrated up from his clothes into his face. He wore a dark, unkempt beard and long straight hair, oiled and brushed severely across his scalp, the combination seeming to hover just above the blanched flesh. Only the two bruises that marked his cheekbones gave his features any depth. Standing in the entrance to the morgue, his hands placed one over the other across his pelvis, this one looked like he teetered at another, more celestial threshold.

No, Padlin said. Or, actually, gestured: his head jerked to the left and then to the right. A fairly emphatic negative, Padlin thought.

He returned to sketching, working out details on the far wall: the wrinkled remnants of clothes hooked at the head of each specimen. A plaid suit and beige derby, the crown sliced in half (matching the cleft in the corpse’s skull). A filthy, crumpled dress, its gingham checks faded in spots, stained coppery in others.

“Why don’t you draw the faces?”

Right behind Padlin’s right ear, like a wheeze from one of the bodies. It made him flinch.

The clerk stepped around and bent down to face Padlin. His breath was warm and sour. Padlin conjured a vague image: this clerk bent over bodies, sucking up morbidity. Grimacing, Padlin averted his eyes.

“It’s difficult, I know, so difficult to confront them. But for the sake of your readers you must.”

He grasped Padlin’s arm and gently tugged him upwards.

“I have to,” Padlin heard himself mumble, “I must complete my sketches.”

“Yes. Of course.” The clerk had him by the elbows, escorting Padlin in a shuffling waltz past the bodies. “And it is my duty to regale you about our institution. Please take note of our washable stone walls, our tile floors. You’re not to miss these marble slabs,” he swept his arm over two callused feet, “or the preserving jets of water. And I must not forget to remark on the plate glass partitions that separate the viewing room from, shall we say, the meat.”

Then this clerk stopped short. “No, pray–” he threw up a hand as if to ward off an intervention from miserable Padlin, although the sketch artist was merely looking for an exit.

“Pray,” he repeated, slowly lowering his arm, “bear with me.” He took a breath, like Forrest waiting for the Bowery Theatre audience to settle down before ending a soliloquy. “You think I underestimate you. No, you need not contradict me. I can see it in your eyes.”

Padlin doubted his eyes were visible, shadowed from the overhead gaslights by the brim of his beaver hat.

“You are an artist. You crave more than the dimensions of a warehouse, or, for that matter, an abattoir. Your mission is to capture the essence of a scene, not the barren facts. And the essence of this wretched place, sir, is the metropolis.”

Padlin worked his features into the most disagreeable configuration possible, but it only seemed to assure the clerk that he was on the right track.

“Look at these dead. They are the sum of the errors of the humanity beyond these walls. They possess the secrets of the city, secrets that must be rooted out. Consider this man–“

The clerk released Padlin and paced over to the head of one marble slab. He bent to the skull of the corpse, the cove with the split cranium, and placed his two hands, gently, on either side, cradling the ruined pate. He raised his own face up to the gaslight and gazed determinedly at Padlin.

The sketch artist still stood where he’d been left, at the foot of the slab. Padlin glowered back. Through the haze created by the spray of the water jet drumming against the dead man’s chest, the clerk, as he caressed the cracked noggin, looked like some revivalist preacher performing a monstrous baptism.

“This man,” Padlin’s captor now said, his words more selective, stamped out in meaningful jabs, “I surmise that this man was vanquished soon after his arrival on these shores. He is a foreigner, I’m sure of it, most likely from the continent. Look at his mustachio. Look at his clothes.” Padlin glanced at the waxed hair on the corpse’s upper lip, at the broad plaid of the wrinkled suit hanging behind the clerk, re-examined the bisected bowler. “But we’re interested in the soul here, in the heart of his demise. To ascertain the fatal combination of this man’s spiritual weakness and this city’s terrible strength.”

The clerk’s hands slapped together, making a puffy pop in the heavy atmosphere. He eyed Padlin, a schoolmaster assuring himself that he had his pupil’s undivided attention.

“And now,” the clerk nodded, his black eyes transfixed on Padlin’s countenance, “this city, finished with the wretch, has disgorged his miserable wreckage. Look: he bares his teeth in death, snarling at the world that abandoned him to so sorry a fate.”

Despite himself, Padlin looked at the corpse’s mouth, his gaze fastening for an unpleasant instant on the rictus leer stretching the dead lips. He turned away, less from distaste than from a barely conscious realization that the expression bore no small resemblance to one of his own hallmarked expressions–and, for the first time, really looked at the neighboring corpse. The owner of the gingham-check dress.

Padlin blinked.

Was it possible?

The clerk caught Padlin’s preoccupation and smoothly moved to the head of his next victim. “Another one of the day’s catch, dragged from the river. So young, yet marked by an immorality thrust upon her by this damnable metropolis.”

The spray was like a fog muffling her features. Padlin stepped over to the clerk and squinted down at the face.

“Nameless, parentless, no kith or kin care to claim this poor wretch–“

Padlin shook his head hard and looked again. It was her.

“What’s the matter?” The clerk reached up and placed a consoling hand on Padlin’s shoulder. “Did you know this one?”

Padlin clenched his teeth, clenched his fists, fearful that he’d knock down the intrusive fool if he said another word, one more word, he’d knock him down.

The clerk persisted: “I understand. At least–” he faltered for a moment, “at least be consoled that now she’ll have a name to place over her grave.”

“No.” Padlin spat the word out, in place of a blow.

“No?”

“No. I knew her.” He took a deep breath of the soggy air. “But I never caught her name.”

The water flowed incessantly from the pipe suspended from the ceiling, cascading upon her bosom, sending a fine spray over her face. It had been a pretty face. To be sure, she’d carried the mark of her race in her wide upper lip, in the brevity of her brow. Yet, to Padlin, ever aware of his incapacity to represent them, the fine carving of her features had, in an unsettling paradox, subverted the blunt outlines.

But the face no longer exhibited any beauty. Padlin would have preferred the usual slackness of dead flesh, the hint of festering to come, anything, to what lay before him. For her countenance now seemed locked in some terrible, fatal moment. It was an alabaster mask, frozen in angular and creased horror.

The clerk’s pale, blue-veined hand suddenly appeared, hovering over the terrible wreckage. “Take care,” he said, and Padlin viewed an all-together new expression on his torturer’s face. “Don’t get too close.” He reached within his heavy black jacket and pulled out a handkerchief. “Here,” he handed it to Padlin, “cover your nose and mouth.” He nodded down at the girl. “Cholera.”

But,” Padlin stammered, “you said she was fished from the river.”

“Yes, deposited there after she died. That’s my guess. But it’s cholera, no doubt. Her face is the terrible evidence.”

Padlin shook his head in vehement denial. No. This did not resemble the arid, shrunken result of the disease. He knew what cholera looked like, knew it all too well. Padlin shuddered. The remembered vision captured in his mind’s eye was terrible, but the awful face before him was the detritus left in the wake of something worse, far worse.

Go to The Hungry Eye, Episode 2

This article originally appeared in issue 2.2 (January, 2002).