Erasure. Historians reverse it, combat it, and with every publication hope they don’t repeat it. Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor, Amy Dru Stanley, and Riv-Ellen Prell have recently shown how to avoid erasure as we rewrite histories of the state and capitalism. Luckily, Susan Sleeper-Smith, Christine Walker, Sara Damiano, and Lorri Glover’s recent monographs advance these aims as innovative studies of eighteenth-century women’s economic might. Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest, Jamaica Ladies, To Her Credit, and Eliza Lucas Pinckney, respectively, discuss women whose economic labor previous scholarship has either underassessed or entirely disregarded as superficial to men’s labor. Anglo-American economies underwent seismic changes during the eighteenth century. These four books improve our understanding of that change by demonstrating that those women’s economic activities were inextricable and essential for, rather than incidental to, the rise of the American state and British empire in that period.

Revisiting Restoration

Women’s economic labor was essential to state function.

This essay discusses the authors’ thematic focus on interconnectivity—the relationship between women’s economic, legal, social, political, and cultural work within emergent capitalism and state power—and (in)dependence—the extent to which early American and British imperial state development depended on women’s work advancing their own material conditions, resisting encroachment by the state, and adapting to changing economic, political, and social conditions in daily life. Contrary to popular misconception, coverture and disenfranchisement did not eradicate women’s economic agency. Women’s economic labor was essential to state function, the economic survival and social standing of middling urbanites and landowning elites, and the economic plasticity of communities during recession.

Each book reflects important differences in how eighteenth-century women wielded economic influence from up and down the socioeconomic ladder. Sometimes, women pursued their own economic goals in tandem with state interests. At other times, women defied the state’s ambitious, organized effort to demonize and weaponize their central role as economic powerbrokers. What’s more, other women continuously tapped their own legal and economic resources and circumvented social expectations regardless of larger political changes underway. Nevertheless, women’s economic work linked to and independent of slavery, great power/imperial competition, and an impossible-to-overstate transformation of the natural and material worlds created nothing short of modernity.

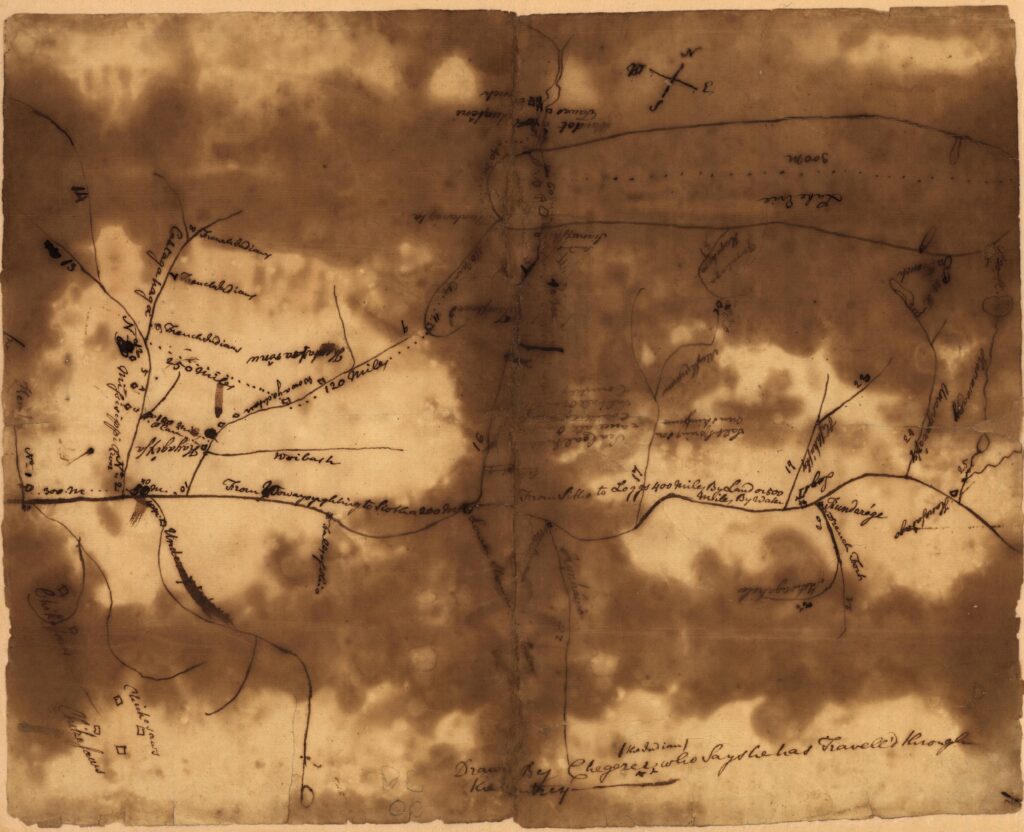

Sleeper-Smith’s Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest shows Indian women in the Ohio River Valley at the nexus of the state and society during times of increasing prosperity, agricultural bounty, and foreign invasion by the newly independent United States. They maintained control, if not deep influence, over the lands they cultivated and the communities they guarded. Corn fields stretching for miles, orchards of European fruit trees planted before sustained contact with the Anglo-Atlantic east, and kinship-based trading networks (as well as control over the fur trade) reflected a deep knowledge of ecosystems that connected them to cultural practices and markets within and beyond their communities. They also integrated French traders as dependent community members and commercial partners while circumventing French control of the Ohio River Valley and of the trading hub at Detroit in particular. Heightened antagonism between British, French, and American groups beginning in the 1750s ran up against Indian women’s orchestration of economy and politics in the region. In everyday life, Indian women’s clothing continuously influenced trade and style across the region, a process resembling an economic and cultural renaissance independent of inter-European competition.

Reliant on Indian women’s agrarian system and economic influence, Indian military abilities expanded and became part of a broader system that Washington and other British and (later) American commanders eventually viewed as a significant challenge to their imperial visions. Such resistance and the women’s continued economic activity, Sleeper-Smith writes, “were more than minor obstacles to western expansion. They constituted a viable alternative to it . . .” (12). Indian women continued to influence treaty negotiations through likeminded diplomats. In spite of their attempts to preserve the independent world they built, President Washington sidestepped peacemaking for plunder. He saw the interconnected strands of economy and agriculture that fueled indigenous prosperity and supported resistance as a reason to kidnap Wabash women and children and establish and maintain a standing army, one that could fight to realize the vision that Hamilton instituted and that could aid Jefferson’s articulation of American sovereignty and potential abroad.

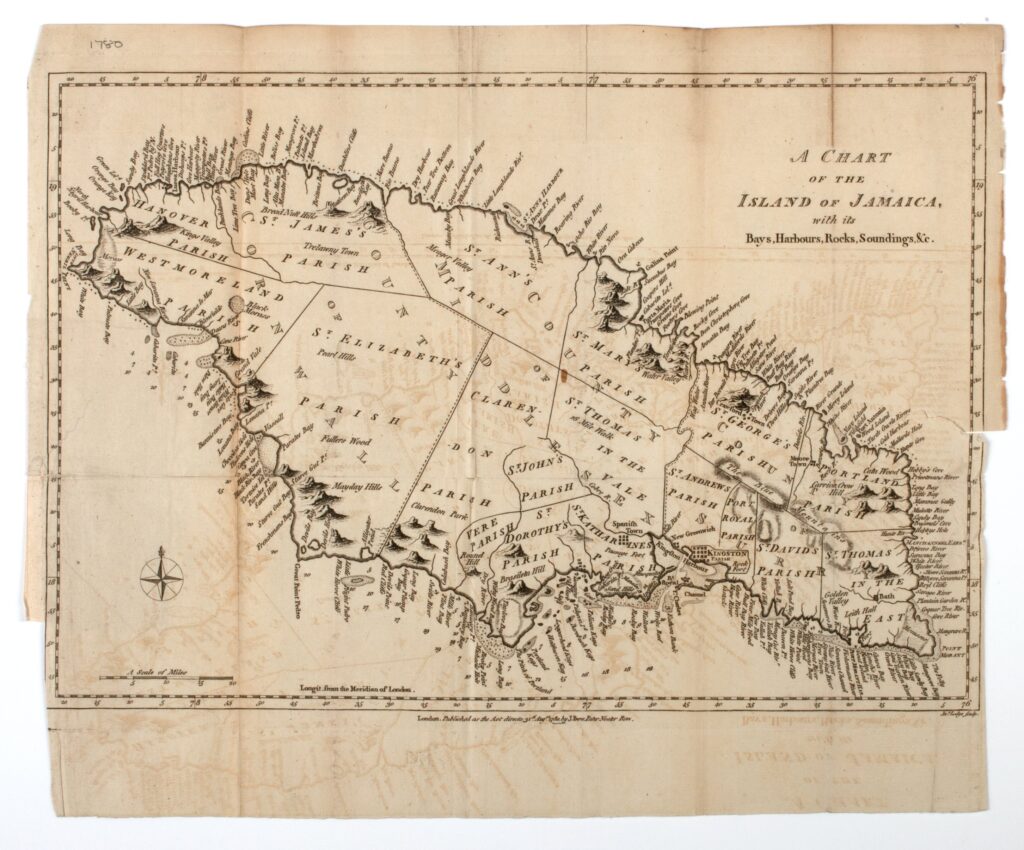

Wabash and other Indian women of the Ohio River Valley resisted French, British, and American state building because empire-making gave no quarter to those seeking an independent co-existence. Those women were Europe’s antithesis. In Jamaica, free and freed women engaged in exactly the opposite effort. The women featured in Walker’s Jamaica Ladies wielded slaveholding as a tool for self-enrichment and to reinforce that system from which the state benefitted hand over fist. Free and freed women, who Walker calls “handmaidens of empire,” sought financial independence and social status and in turn rendered the growing British commercial empire dependent on them as indispensable providers of enslaved people’s labor (5). The British state and slaveholding women in Jamaica were therefore co-beneficiaries of slavery.

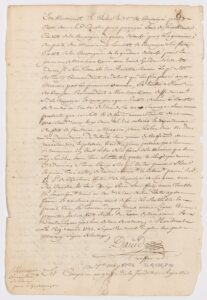

This remained true from Britain’s earliest efforts to expand its economic footprint in the Caribbean. Three generations of women, some moderately wealthy, took advantage of England’s desire to increase Jamaica’s population and ensure British control of the island. Once there, those women enslaved other women and men, began commercial enterprises of their own to grow their personal wealth and status, and inherited enslaved people which maintained their wealth. These practices deepened their connections to profitable enterprise and the construction of the British imperial state. Even those enslaved people who free women manumitted sometimes continued the cycle, enslaving others to establish good economic and social standing of their own. The second and third generations, concentrated mostly in Kingston, ensured the long-term survival of British trade and manufacturing. In short, slaveholding women in Jamaica shielded Britain’s empire, supported its grand commercial ambitions, and advanced their own commercial and social interests while stripping the freedom and commercial prospects of those they enslaved.

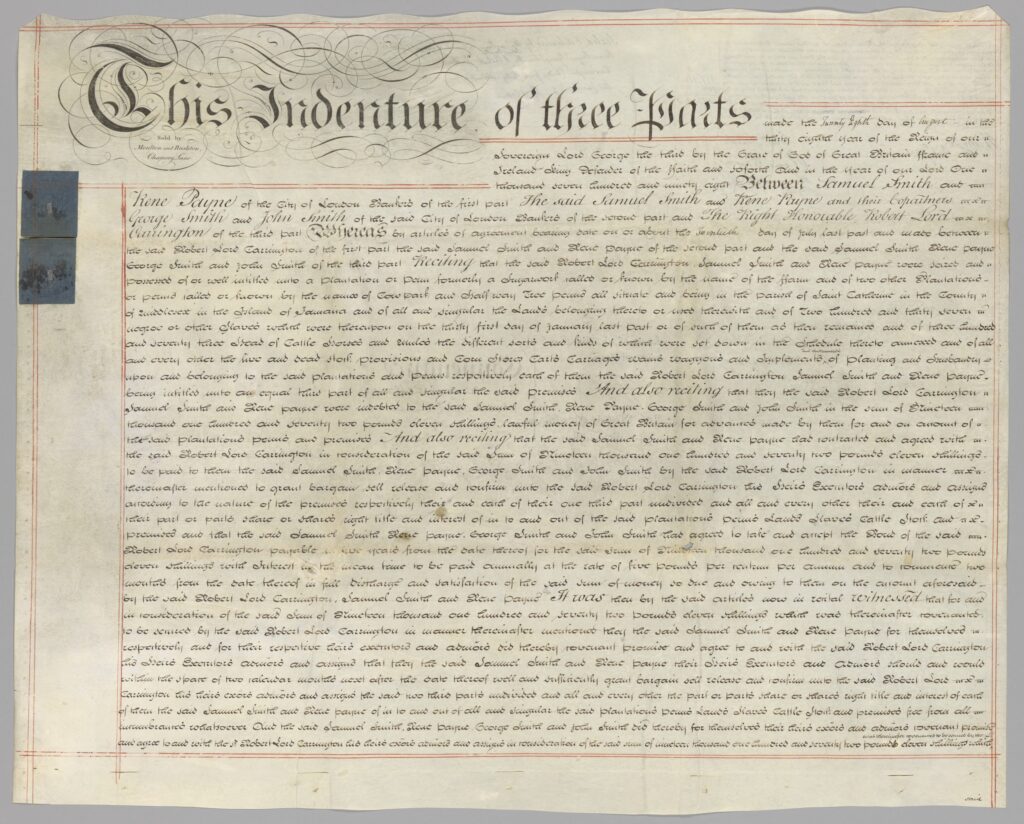

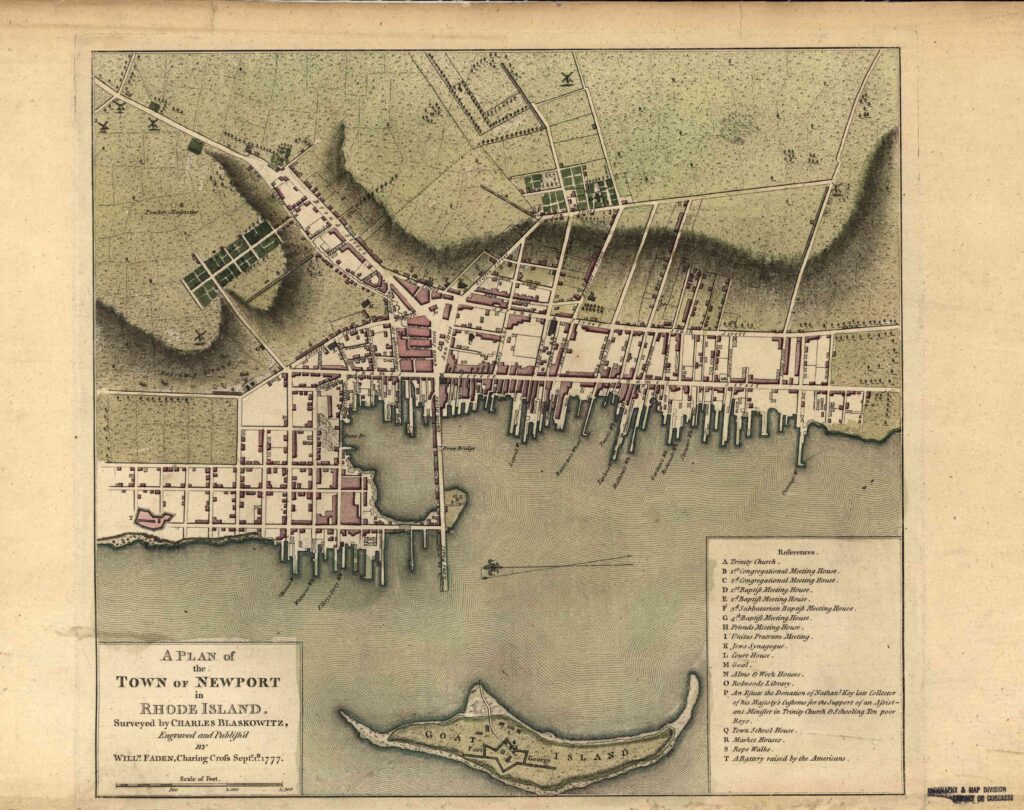

The colonial New England women in Damiano’s To Her Credit were not the antithesis to American state building, nor did they stand to gain alongside the state like slaveholding women in Jamaica. Rather, their own financial independence waned as New England’s political economy changed between 1730 and the American Revolution. Damiano’s social and gendered political economic history of Boston, Massachusetts, and Newport, Rhode Island, argues that free white urban women managed family, business, and community financial ties vital to the political economic function of colonial governments. In this period, urban women wielded significant power over men’s economic lives and through them over the state and private enterprise. That began to change mid-century. The Revolution as well as changes in legal regimes and political and economic culture diminished women’s financial “authority” (4). That said, at no time did women cease to exert considerable financial power through their use of credit and in turn created “both financial networks and the state” (4).

Women in these settings were highly skilled economic agents, as well as financial and legal strategists. Indeed, their economic labor acted as a bulwark against economic upheaval and shocks such as war and the deaths of men who engaged in notoriously dangerous maritime work. This was especially true for Mary Prince, who maintained her family’s good credit by managing their retail shop while Joseph, her husband, was at sea. In one instance, Mary paid a £96 debt in full that her husband incurred a year prior. British North America was especially prone to economic shock. Materially, the colonies suffered from a lack of circulating coinage and inefficient lawmaking and enforcement power to regulate the value of paper currency emissions. Women were economic first responders during periods of severe price inflation. Finally, and similarly to Jamaican women who inherited enslaved people as generational wealth, women’s central place in the New England family ingrained inextricable links between New England industries and commerce. The American state and society never stopped depending on New England’s women even as their labor was devalued through the tumult of rising capitalism. So too did women’s connectedness to the state-building enterprise remain despite their general loss of financial power.

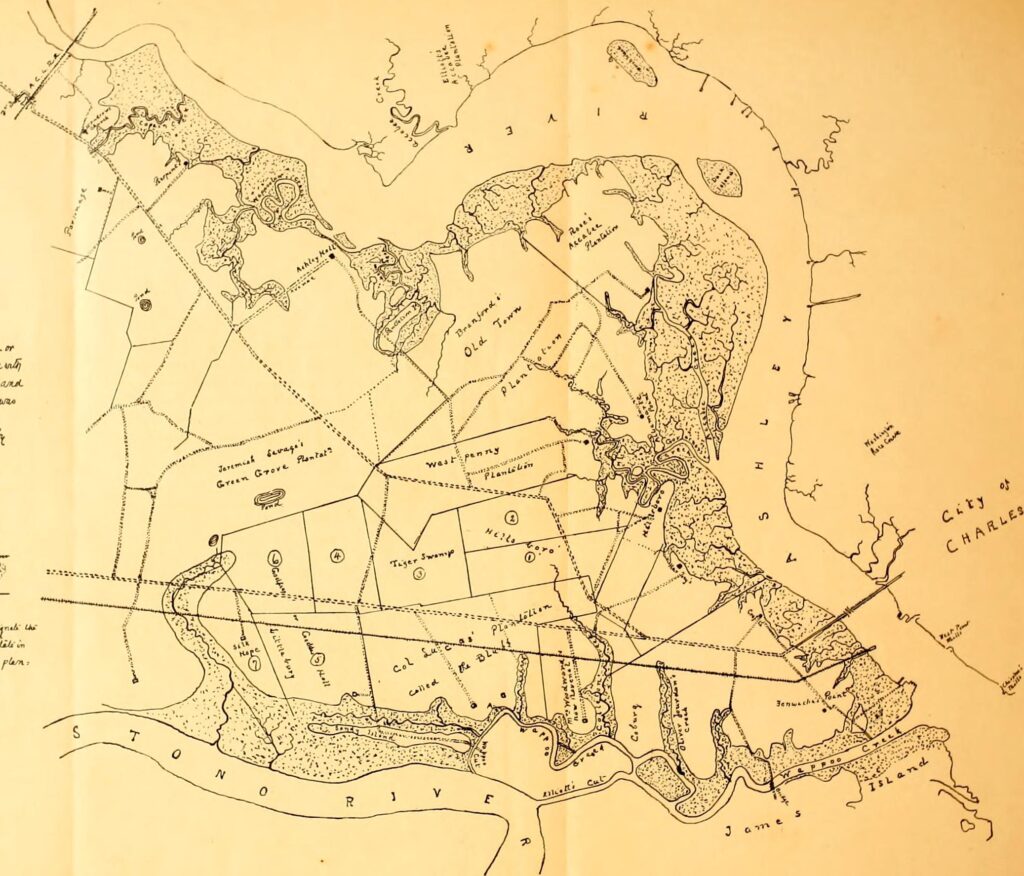

Wealth, unrivaled social status, and an extraordinary capacity for management made Eliza Lucas Pinckney, the main subject of Glover’s book, unlikely to ever fit the stereotypical mold of mother-as-nurturer to statesmen and social beauties. “Eliza,” Glover writes, “reflected the eighteenth century even when she refracted it” (6). Independent to her core and from an early age, Pinckney gradually acquired control of her family’s commercial affairs and became “a consummate planter-patriarch” (5). For example, she overcame unscrupulous sabotage from an expert dye maker to turn South Carolina into a major exporter and source of revenue for the British empire. She also circumvented her father’s preference that she relinquish agriculture and her “commercial schemes” and submit to being a wife and mother. She occupied the planter-patriarch role so effectively that her status alone made her two sons eligible to reach rarified political heights and allowed her daughter to further solidify the Pinckneys as an estimable family. She claimed her own life as a woman in a world favorable to free-born white men to create a life “for Posterity” “adeptly, proudly, and independently” (2, 6).

With all of this said, she was far from self-made. Women like Pinckney, though successful in reigning over the social and economic life of South Carolina’s elite society, relied on enslaved labor to acquire that sort of wealth and prestige. Quash, who took the name John Williams just before his emancipation, built the vats necessary for indigo production. Pinckney led her family into American patriotism, folding South Carolina further into the Revolution and preserving slavery for the nation. “After the Revolution, the Pinckney family, like Lowcountry elites generally, retained an unshakable commitment to slavery” (218). Charles, Eliza’s husband and a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, supported provisions that would uphold slavery in South Carolina and the country as a whole as it had been under British rule. Like Britain before 1776 and South Carolina after 1787, she retained her dependence on slavery to live a life of self-satisfaction. She was of and an outlier in her society, ancillary to the American state and among a privileged few who conducted her affairs the same before the founding as she did after it. Perhaps, as Glover writes, “it seemed as if the Revolution had never happened” with the Pinckneys’ ties to slavery unbroken after the war (218).

Individually, these books reveal important differences in how women’s labor intersected with state-building while standing apart from it. Read together, they also demonstrate that whatever the state stood to gain always was secondary to the world these women never stopped making for themselves. Walker puts it best regarding the free and freed women of Jamaica. “Recognizing women as powerful agents of slavery and colonialism calls into question the extent to which normative European gender ideologies were imported and adopted across the Atlantic” (9). Powerful agents. Not just agents. Continuous focus on the state’s strengths and inadequacies risks further erasure of women’s power as economic agents, some of whom helped decide the economic future of entire colonies through slavery, while others’ day-to-day business and legal acumen supported their husband’s credit. With this new knowledge at our disposal, history that shows women possessing only agency and exercising free will, likewise borders on disingenuous. It ignores their historical power. All four books show that moving past agency, past a state’s strengths and weaknesses, and towards “everyday practices” (Damiano 5) can further restore women as historical forces in future scholarship on the rise and development of the American state.

Let us not be mistaken that these books are more about the state than the women or societies discussed. In the case of Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest, for example, comprehending the political economy of Indian resistance in spite of removal is as much about recovering the societies that it destroyed as it is about the state’s preference for force over co-existence. In Eliza Lucas Pinckney, Glover presents one woman’s life against the equally important backdrop of American independence, self-government, and the work of managing any elite family’s financial empire. These authors remind readers to see subjects for who they were as well as what they made possible.

For everyone, not just historians, Sleeper-Smith, Walker, Damiano, and Glover’s books arrived on shelves at an especially important moment. People today have their minds eye set on a new era, one defined yet again by interconnectedness and (in)dependence. Presidential prerogative, divisive politics over government spending and federal debt, the disproportionate drop in women’s labor force participation during the pandemic, and Supreme Court rulings of the last decade have led many to question the historical purpose of government, its development through the present, and the state and economy’s acute dependence on women who do not always enjoy equal protection from either. Sleeper-Smith, Walker, Damiano, and Glover have made it impossible to imagine that women’s economic work was not also inextricably linked to the rise of banking and commercial law, regulatory institutions and law enforcement, international trade and investment, and immigration policy, to name a few. Their research methods and innovative use of source material also provide models for future articles, monographs, and dissertations. Consequently, history and the work historians do, as well as the aspects of our daily lives informed by scholarship, may all be better off.

Further Reading

Amy Dru Stanley, “Histories of Capitalism and Sex Difference,” Journal of the Early Republic 36 (Summer 2016): 343-50.

Max M. Edling, Hercules in the Cradle: War, Money, and the American State, 1783-1867 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Laura F. Edwards, Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

Riv-Ellen Prell, “The Economic Turn in American Jewish History: When Women (Mostly) Disappeared,” American Jewish History 103 (October 2019): 485-512.

Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor, Ties that Buy: Women and Commerce in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009).

Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor, “Gender’s Value in the History of Capitalism,” Journal of the Early Republic 36 (Winter 2016): 613-35.

William J. Novak, “The ‘Myth’ of the Weak American State,” American Historical Review 113 (June 2008): 752-72.

Michael John Witgen, Seeing Red: Indigenous Land, American Expansion, and the Political Economy of Plunder in North America (Williamsburg and Chapel Hill: The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and The University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

This article originally appeared in March 2023.

Jonah Estess is a Ph.D. candidate in the American University (AU) Department of History. His research explores the history of American political economy, capitalism, and money in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His research has been supported through fellowships and grants from the Library Company of Philadelphia, American Society for Legal History, the American Numismatic Society, and the AU history department. Jonah’s other publications have appeared in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, the Society for US Intellectual History Blog, H-Net, and The Washington Post.