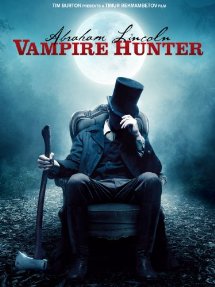

While many films featuring Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president of the United States, were made in the early days of American cinema, relatively few movies have been made featuring him since 1940. In part, this has to do with growing resistance on the part of film viewers to watching quasi-educational movies about great white men. In part, it also arises from the difficulties of dealing with Lincoln’s own reputation. Leaders of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s paid lip service to Lincoln as the man who had emancipated the slaves, but his racial views were at some remove from what today would be regarded as progressive. Steven Spielberg managed to get around this problem in his 2012 biopic by focusing on a very narrow chronological period: the few weeks in early 1865 in which Lincoln battled to get a draft of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery through the House of Representatives. Other Lincoln films in recent years have dealt with him either by focusing on his assassination and its aftermath (The Conspirator, 2011) or making him essentially a comedy character (in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, 1989, he helps high-school kids with their history reports, finishing with a parody of his Gettysburg Address). In 2012, Timur Bekmambetov—like Spielberg—brought Lincoln back to the screen as a hero. Unlike Spielberg, he did so in a horror movie: Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.

The film opens with the Lincoln family living in Indiana. When a young friend of Abe’s (Lux Haney-Jardine), a black boy named Will Johnson (Curtis Harris), is seized by slavers, Abe picks up an axe and tries to save him. When Abe himself is threatened with a bull-whip, his father (Joseph Mawle) intervenes, provoking a quarrel with his employer Jack Barts (Marton Csokas), to whom the family owes money. Barts fires the elder Lincoln and demands he pay off the debt immediately. When he refuses, Barts threatens him. The Lincoln family quickly learns what the threat means: Abe’s mother, Nancy Hanks (Robin McLeavy) is bitten by a vampire and dies. Abe is prevented from seeking vengeance by his father but, nine years later, when his father dies, Abe (now played by Benjamin Walker) sets off to kill Barts. He fails, discovers in the process that Barts is a vampire, and is rescued by another vampire, Henry Sturges (Dominic Cooper). Sturges is a “good” vampire who wants vengeance against vampires for murdering his sweetheart. But since vampires can’t kill other vampires, he needs a human agent. Under his tutelage, Lincoln trains as a vampire hunter, choosing an axe (he’s been a rail-splitter, get it?) with a silver edge as his weapon of choice. He is soon living in Springfield, working in the store owned by Joshua Speed (Jimmi Simpson), romancing Mary Todd (Mary Elizabeth Winstead, who bears a strong resemblance to the real Todd), and spending some of his nights bumping off vampires. One of these is Jack Barts. But Lincoln slowly becomes aware (as Sturges has always known) that a titanic struggle is going on in the background between free humans and vampires, who have come to dominate the American South, and thus have also gained control over millions of enslaved African Americans, whose blood keeps their vampire masters alive. Lincoln realizes that the dominance of vampires in the South can best be undermined through politics, and he embarks upon the career that will take him to the presidency.

The film opens with the Lincoln family living in Indiana. When a young friend of Abe’s (Lux Haney-Jardine), a black boy named Will Johnson (Curtis Harris), is seized by slavers, Abe picks up an axe and tries to save him. When Abe himself is threatened with a bull-whip, his father (Joseph Mawle) intervenes, provoking a quarrel with his employer Jack Barts (Marton Csokas), to whom the family owes money. Barts fires the elder Lincoln and demands he pay off the debt immediately. When he refuses, Barts threatens him. The Lincoln family quickly learns what the threat means: Abe’s mother, Nancy Hanks (Robin McLeavy) is bitten by a vampire and dies. Abe is prevented from seeking vengeance by his father but, nine years later, when his father dies, Abe (now played by Benjamin Walker) sets off to kill Barts. He fails, discovers in the process that Barts is a vampire, and is rescued by another vampire, Henry Sturges (Dominic Cooper). Sturges is a “good” vampire who wants vengeance against vampires for murdering his sweetheart. But since vampires can’t kill other vampires, he needs a human agent. Under his tutelage, Lincoln trains as a vampire hunter, choosing an axe (he’s been a rail-splitter, get it?) with a silver edge as his weapon of choice. He is soon living in Springfield, working in the store owned by Joshua Speed (Jimmi Simpson), romancing Mary Todd (Mary Elizabeth Winstead, who bears a strong resemblance to the real Todd), and spending some of his nights bumping off vampires. One of these is Jack Barts. But Lincoln slowly becomes aware (as Sturges has always known) that a titanic struggle is going on in the background between free humans and vampires, who have come to dominate the American South, and thus have also gained control over millions of enslaved African Americans, whose blood keeps their vampire masters alive. Lincoln realizes that the dominance of vampires in the South can best be undermined through politics, and he embarks upon the career that will take him to the presidency.

Following the secession of eleven Southern states to form the Confederacy, the Civil War begins when the Southerners open fire on Fort Sumter. But there are effectively two powers in the South: the Confederate government, headed by Jefferson Davis (John Rothman), and the vampire network, led by Adam (Rufus Sewell) and his sister Vadoma (Erin Wasson). The vampires are supportive of slavery since, as Adam explains, slaves have always been part of civilization. Lincoln is made to suffer personally for his political views: Vadoma infiltrates the White House and kills the Lincolns’ son Willie (Cameron M. Brown). The climax of the Civil War—and the film—come at Gettysburg in July 1863. Initially, the Northern army appears to be winning. But Adam has brokered a deal with Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, so that vampires—who cannot be easily killed—join the ranks of the Confederate army. The Southern troops, with their vampire reinforcements, begin to turn the tide of the battle. Lincoln has realized that only weapons made of silver (fatal to vampires) can win the battle, and that he himself must once again pick up his axe. He orders the confiscation of all silver in the Washington area to be melted down into weapons. Joshua Speed, frustrated with Lincoln’s actions, tells Adam that a northbound train is carrying all of the silver bound for the Union army. This defection is a ruse, however—the train is carrying only rocks. Lincoln kills Adam in a furious battle on the doomed train. In the meantime, former slaves smuggle the weapons via the Underground Railroad to the Northern troops at Gettysburg, who find that all the Confederate soldiers—including vampires—are now vulnerable to their guns and bayonets. When Vadoma arrives in the Northern encampment intent on killing Lincoln’s wife, Mary instead kills her by inserting a silver necklace into the barrel of a rifle before she pulls the trigger. With vampire support gone, the Confederacy is defeated and slavery ended. Lincoln, offered immortality by Sturges (he could become a vampire himself) sets off for Ford’s Theatre and his own brand of historical immortality.

It is never clear what kind of movie Bekmambetov has made, which may explain its relative failure at the box office. It could be a comedy, but there is little real humor. It could be a horror film, though there is comparatively little gore. Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter has some of the essential elements of a historical movie: it features real people and real events, with some of them (the growing controversy over slavery, the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, and the Emancipation Proclamation) underlined by the use of intertitles. Extracts from Lincoln’s first inaugural address are featured, against the backdrop of a half-finished Capitol building, together with the second half of his Gettysburg Address. Other historical movies incorporating Lincoln are referenced. The battle sequences hark back to D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Abraham Lincoln (1930). The sequences featuring Lincoln with Mary Todd and an uncredited Stephen A. Douglas are very reminiscent of John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) and, even more obviously, John Cromwell’s Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940). The shots of Lincoln and Mary Todd at the party in Springfield are particularly close to Cromwell’s film, although Bekmambetov’s Lincoln—echoing his athletic skills as a vampire-killer—is much more adept at dancing. Some of the biographical material in the film is accurate: Lincoln’s mother died in 1818, his son Willie died in the White House less than a year after the start of the Civil War, and there were strong tensions in the marriage of Abraham and Mary Lincoln, explained in the movie by the fact that he had never told her he was a vampire hunter. (In fact, earlier in the film, he had confessed to this, but she thought he was joking.)

Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter shows us a Lincoln who physically (especially once he grows a beard) resembles the martyred president. Yet at the same time it greatly simplifies his views on race, foregrounding his antislavery sentiments but not his often limited views on equal rights. From the beginning of the film (attempting to rescue Will from slavers) he is instinctively opposed to the institution of slavery. During the course of the film, he eventually becomes the “Great Emancipator.” But this antislavery crusade also has a revisionist touch: Will (now Anthony Mackie) has escaped from slavery and become a friend and ally of Lincoln in the White House. He fights alongside Lincoln in the climactic battle against vampires led by Adam on the train to Gettysburg. Moreover, it is African Americans—via the Underground Railroad—who carry the silver weapons to Gettysburg that ensure the Northern victory. In Bekmambetov’s movie, as in history, African Americans fought to win their own freedom. It was not simply conferred upon them. In the struggle against vampires, moreover, women play a part: just as Lincoln (eventually) kills Jack Barts, the vampire who killed his mother, Mary Lincoln kills Vadoma, the vampire who killed her son. The film ends equivocally: Sturges, ageless as a vampire, sits in a bar in today’s Washington, D.C., attempting to recruit a successor to Lincoln as vampire hunter. Vampires apparently still pose a threat to the United States and, like a much darker version of Jefferson Smith in Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), someone is needed to pick up the mantle once carried by Lincoln.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.4.5 (September, 2013).