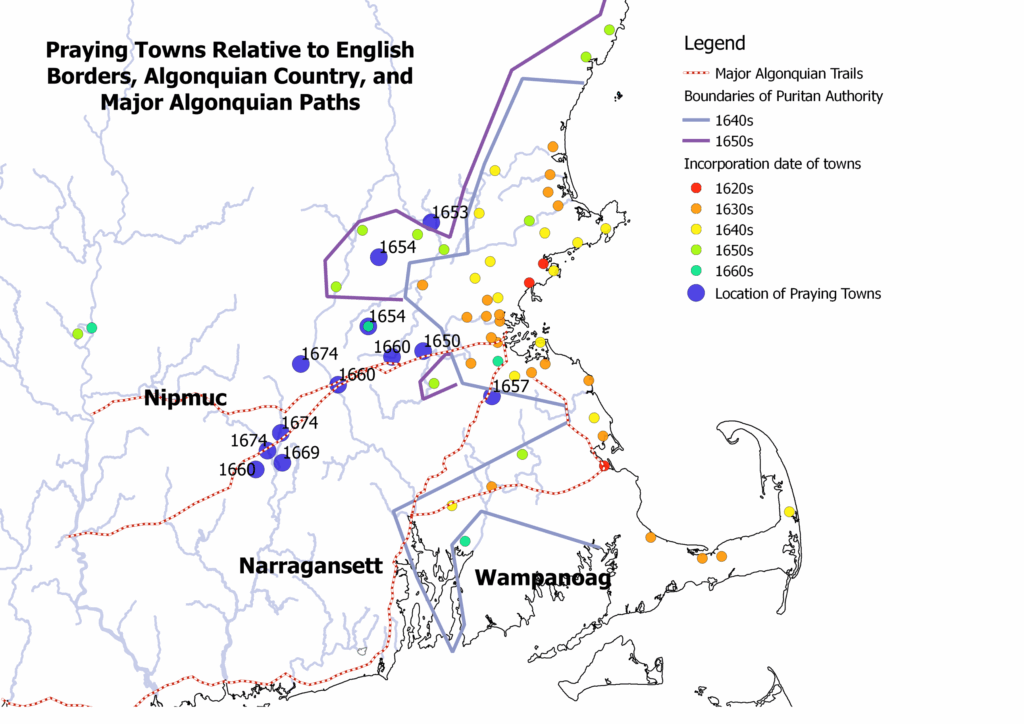

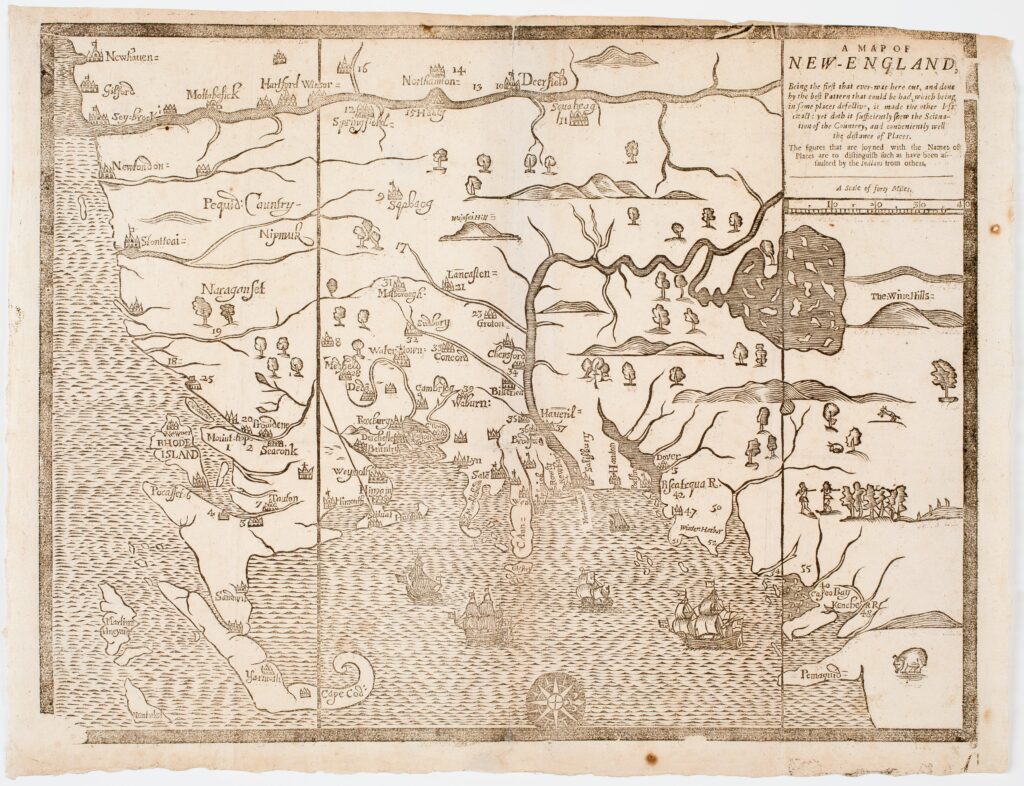

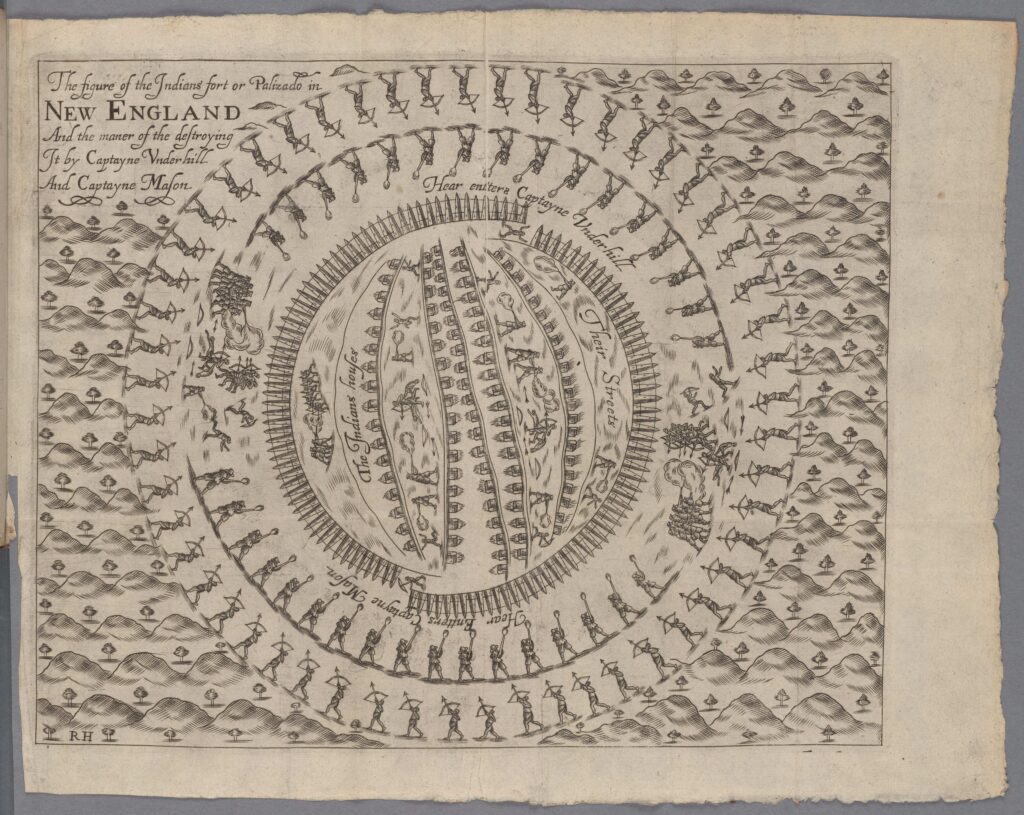

The history of Puritan-Native relations has long been in debate. Although the chronology of the events remains in consensus, historians debate the implications of these events. In a compelling new book, religion and philosophy scholar Matthew Tuininga rewrites the history of Puritan-Native relations in its entirety. In addition to offering a new perspective to the existing historiography, Tuininga documents the events in narrative form, dividing his book into three chronologically consecutive sections. The first part discusses the initial encounters between Puritans and Native Americans upon the former’s arrival. This section contextualizes the motivations for the Puritans to travel across the Atlantic and details how the Puritans settled and established themselves in the Americas. The second section discusses the climactic build up to the Pequot War, the first monumental confrontation between the Puritans and Natives. This war’s aftermath led to devastation for the Indigenous population; many Natives lost their land and much of their autonomy. The third and final section reveals the ultimate end to Indigenous control in the region. After one last attempt to assert Native authority and independence, in what is today called King Philip’s War, Indigenous people were violently squelched by the Puritans. The history of Puritan-Native relations prior to, in between, and during the earlier Pequot War and the subsequent King Philip’s war has long been in contention. In addition to the wars, this period witnessed numerous “praying towns” emerge throughout New England. Although most residents of these towns did not convert, a good portion of them adopted English culture and Puritanism and studied the Bible under the leadership of John Eliot. While many scholars contend that the Puritans’ attacks on and conversion of Natives were oppositional missions, Tuininga sees both as elements of the same mission and crafts and engaging and accessible narrative to propel his view.

Attempting to Merge Narratives: An Alternative History of Puritan-Native Relations

Tuininga contends that although they had disagreements about how to execute their Wars of the Lord, both missionaries and warriors were in consensus about waging an intentional Godly war.

Matthew Tuininga’s recent publication, The Wars of the Lord, offers a new addition to the historiography of Puritan-Native relations, a perspective that dismisses both the “morality tale” of upstanding people fleeing tyranny “to establish religious liberty and democracy,” and the position that Puritans were racially motivated (4). Using numerous primary sources, including sermons and statements of essential Puritan figures, Tuininga argues that serving God was the driving motive for every Puritan action, including how they handled so-called pagans. Scholars dispute whether to characterize Puritan attacks on Natives as a racial or cultural war. According to Tuininga, it was a religious war (4). There was no difference between their missionary campaigns and wars; all were in the name of the Lord. Tuininga tries to rectify the claims of Puritan hypocrisy without justifying their actions as an unfortunate, but inevitable, outcome. The contemporary critical perspective finds the Puritans a hypocritical people who professed themselves as God’s nation, kind and just, but whose actions revealed violent, perhaps even genocidal tendencies and whose intentions sought blood instead of peace. This position follows historians like Lisa Brooks, who recontextualizes Puritan-Native relations through oft-ignored Indigenous perspectives. The charitable perspective, by contrast, asserts that the Puritans truly exemplified their professed piety and justice, yet, circumstantially, could not avoid the wars that led to severe consequences. Historians of the mid-twentieth century, such as Alden Vuaghn, determined that the Puritans had a “relatively humane, considerate, and just policy” towards Indigenous people. Tuininga takes a seemingly balanced stance between these positions, claiming their attacks were neither defensive nor hypocritical. Yet, although Tuininga writes vividly and thoroughly, there appears to be some lack of nuance in his argument. Tuininga contends that although they had disagreements about how to execute their Wars of the Lord, both missionaries and warriors were in consensus about waging an intentional Godly war.

To explain this, Tuininga meticulously arranges his book not only chronologically, but thematically, placing the progression of militaristic strategies alongside the corresponding development of praying towns. This arrangement could indicate how colonists waged war only once they determined that missionizing was an unsuccessful path to achieve the Lord’s work. Such logic could account for the variability between each Puritan generation. As historian Alden Vaughan has argued, the earlier Puritans may have wished for the “peaceful” assimilation and integration of Natives, yet later Puritans resorted to militaristic confrontation. The fault here lies in the chronology. Those who supported the war and those who established the praying towns were contemporaries who disagreed, not living in different eras as Vaughan presents. As Tuininga himself notes, the praying towns established in the decades leading up to King Philip’s War were not favored by all Puritans, with most viewing Natives in these towns as pagan (277). The goal of the missionaries did not agree with the goal of most Puritans.

Tuininga clarifies that these different Puritan positions, one leaning towards what many would consider a genocide, and another towards missionizing, only debated the approach of their mission, not on the mission itself. Praying towns had obvious Godly purposes, and Tuininga shows how most militaristic moves and strategies were similarly made with God in mind, quoting captains who justified their genocidal acts as a war on “Amalek,” the biblical arch-rivals to God’s people (280). Yet, if their war was religious, not hypocritical and racial, one could ask why religious Natives rarely were able to culturally strip themselves enough to become wholly Puritan; they were largely alienated prior to the war and were attacked by Puritans during the war (274). Tuininga himself writes how Eliot’s praying towns faced resistance (187) and that “most pious colonists viewed the Indians as the worst of men” (192). Although policies toward such Natives were technically equal to those for Puritans, judges and juries did not always treat them with the same fairness (193). The evangelizing of Eliot and Mayhew’s praying towns sought to treat Natives as religious equals, while the war sought to treat them as a distinct cultural entity. For instance, Mary Rowlandson, a Puritan woman taken captive during King Philip’s War, describes the Praying Indians as people without scruples who displayed vicious acts of terror on the Puritans. This inconsistency negates Tuininga’s claim that Puritans didn’t see Natives in racial terms. If faithful Natives adopted English culture and Puritan religion, the primary difference between them and New Englanders was race; while ministers of praying towns may have ignored race, Puritans in support of war acknowledged race and became prejudiced against it. Daniel Gookin, the New England author of Puritan-Native relations who was sympathetic to praying towns, proclaimed that he could not join the multitudes of Puritans to cast all Natives in the same group (262). Based on Tuininga’s book alone, one can question whether those who waged war and those who professed to missionize upheld the same missions, and how we should assess their whether they were both Godly.

The only reconciliation between these two missions is cultural, not religious. Tuininga uses the term “genocide” to describe the events of King Philip’s War, corroborating the contemporary argument of Puritan hypocrisy. Yet, genocide was not a consistent mission between missionaries and warriors. Tuininga’s perspective only works if, rather than a physical genocide, a cultural genocide, took place. Both the praying towns and wars sought to strip Natives of their culture; the praying towns forced Natives to adopt English culture in various ways, such as cutting Indigenous hair, and Puritans concluded their wars with treaties that explicitly eradicated Native identity (88). Yet, if one acknowledges a physical genocide of the war, no such consistency exists between these two missions. Praying towns wanted the assimilation, and thereby the existence, of the Natives, while physical genocide desired their annihilation. Bearing in mind that the UN definition of genocide requires intention of the act, it is difficult to confidently assert whether or not a physical genocide occurred 350 years ago. Tuininga’s assumption that they waged a religious war appears to purport an intention of genocide, one that could not be consistent with the praying town’s cultural genocide. Such inconsistencies in Tuininga’s argument are rooted in his undefined interpretation of “genocide,” a word he uses explicitly to describe King Philip’s War (3). He never elucidates what he means by the term, creating a vague and ambiguous account that makes it difficult to either accept or critique.

Not only does Tuininga avoid defining “genocide,” he also provides no interpretation for the term “religious,” the most integral word for his argument. The obscurity of “religious” invites complications for those seemingly non-religious Puritan-Native interactions, particularly economic. As devout as the Puritans were, they still cared about financial security and success. Tuininga himself notes how Eliot speculated that the reason Puritans “were in danger of doing the same” destruction and depopulation as the Spanish was because “they desired Indian’s land” (258). One can potentially ignore the Puritan’s economic relationship with Natives and Native land by correctly identifying the Puritan—and more broadly, Protestants—dislike of idleness. Economic activity was a way to do the Lord’s work and keep busy. Yet, although one could argue that such economic pursuits were religiously motivated, some of the Puritans’ transactions contradicted their religious doctrine. Puritans relied on the Natives for the consumption of goods, particularly liquor, which they restricted for themselves. Such business deals do indicate hypocrisy rather than simply strict adherence to their doctrines and beliefs. It is difficult to establish or negate a religious premise in every Puritan-Native interaction, especially in the field of economics, though, because Tuininga’s term is under-theorized.

Finally, as fascinating as it is to follow Tuininga’s narrative style, the lack of explicit engagement with secondary sources limits a reader’s ability to evaluate his historiographical intervention. Tuininga introduces a completely new argument, yet, besides for his preface, he does not explicitly write in what ways he rejects previous historical narratives. Since the 1990s, the question of whether the Puritans committed genocide against the Pequot people has received significant attention and debate. Jeffery Ostler, a historian of Native American studies, has written an entire article dedicated to the conversation among existing scholarship surrounding the process of definition and application of genocide in early America; he concludes with the importance of definition alongside other “points of engagement” that encourage Native agency of their history. Tuininga’s story is compelling, but it is undermined by the lack of clearly defined terminology of words that are quintessential to his argument, while limiting his evidence to biblical or Puritan sources. The additional absence of direct discourse with previous scholarship makes his work less defensible. To his credit, Tuininga attempted what no other scholar has done previously. While most of the scholarship considers the two narratives independently, he attempted to fuse them, offering an entirely new image of Puritan-Native relations.

Further reading:

Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (Yale University Press, 2019).

Jeffery Ostler, “Genocide and American Indian History,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, March, 2, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.3.

Mary Rowlandson, Narrative of Mrs. Rowlandson; Narrative of the captivity and removes of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson; Sovereignty & goodness of God. Mass[achusetts] Sabbath School Society, 1856.

Matthew J. Tuininga, The Wars of the Lord: The Puritan Conquest of America’s First People (Oxford University Press, 2025).

Alden Vaughan, New England Frontier, Puritans and Indians 1620–1675, 3rd ed. (University of Oklahoma Press, 1995).

This article originally appeared in December 2025.

Yita Khanin is an MA student in Prehistoric Archaeology at Hebrew University. She recently graduated from Yeshiva University’s Stern College for Women with a BA in History and Sociology. Khanin specializes in Indigenous and Nomadic studies and is in the process of publishing her undergraduate thesis on Russia’s reindeer pastoralists, analyzing Indigenous people’s relationship to the State, in addition to beginning her MA thesis on Bedouin pastoralists. In the coming year she will begin her PhD in Indigenous and Nomadic studies of the Levant.

She has published several articles in and served on the editorial board of her university’s history journal.