Public education is an idea, not a structure. The idea is that every citizen must have access to the culture and the means of enriching that culture. It arises from the belief that we are all equal as citizens, and that we all thereby have rights and obligations to serve the community as well as ourselves. To meet those obligations, we must use our informed intelligence. Schools for all assure the intelligence of the people, the necessary equipment of a healthy democracy. A wise democracy invests in that equipment.

—Theodore R. Sizer, Horace’s Hope (1996)

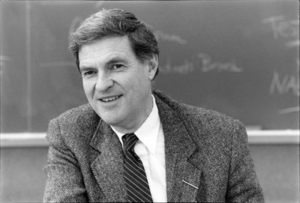

In late November, an estimated thousand mourners, including Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, gathered at Memorial Church at Harvard University to honor the life and work of Theodore R. Sizer, the internationally recognized education reformer who died this past October. (Sizer, a friend to this publication, co-authored a piece with his wife, Nancy, on the misguided emphasis on standardized testing for the July 2008 issue of Common-Place.) Sizer received his Ph.D. in History in 1961, writing his thesis under the directorship of Bernard Bailyn on the so-called “Committee of Ten” who sought to reform American education in the 1890s. Published by Yale University Press in 1964, Secondary Schools at the Turn of the Century became the first of eleven books Sizer wrote or edited. Over the course of the next 45 years, his productivity as a scholar proceeded alongside a career that included serving as dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Headmaster of Phillips Andover Academy, Professor of Education at Brown, and spearheading a reform initiative that came to be known as the Coalition of Essential Schools. It was followed about a decade later by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, a broader effort at Brown that sponsors research and analysis. Rarely has any figure in modern intellectual life so successfully harnessed the power of private institutions for public good, or achieved the fusion of thought and action, that Sizer did in his remarkable career.

The seedbed of that career was a childhood and training saturated in the culture and traditions of New England. New England, of course, is the cradle of American educational civilization. Early colonies such as Hartford and New Haven (Sizer was born and buried in the town of Bethany, situated between the two cities), mandated free public schools within a decade of their founding in the 1630s, as did Massachusetts. But the region was also the seedbed of private academies such as Phillips Academy Andover, founded in 1778, where Sizer served as headmaster two centuries later. For all their differences, these educational institutions were characterized by a powerful communitarian spirit in their mission, and an avowedly moral orientation that stressed the importance of independent-minded people who would also be civic-minded participants in public life—a seeming contradiction that Sizer finessed with notable grace in forging public-private partnerships at Harvard, Brown, and the Coalition, founded in 1984. These characteristics remained discernible even in the nineteenth century, when strong-minded reformers like Horace Mann sought to adapt public schools to the needs of an emerging industrial capitalist order. Mann no less than Cotton Mather would have endorsed deceptively simple Coalition precepts such as “The school should focus on helping young people learn to use their minds well,” or “The school’s goals should apply to all students.” (For more on these and other essential principles, see the CES website.)

Sizer had the good fortune of coming of age as the American Century crested; a beneficiary of the G.I. Bill, he entered university life and became the youngest dean in the history of Harvard at age 31 as much because of the rapid expansion of postwar academia as for his evident talent and social skills. But he was at the helm of Phillips Andover during the rocky 1970s, and was keenly aware of the economic challenges facing public education in the face of receding collective commitment. In this difficult environment, Sizer’s commitment to egalitarianism in education guided his work, whether in making co-education a condition of his acceptance of the Andover post, creating a free math and science program for minority students while there, or in founding a charter public high school in central Massachusetts (and serving as co-principal with Nancy Sizer in 1998-99 to plug a personnel hole).

Sizer was sometimes characterized as a “progressive” educator, and the label makes sense—to a point. Certainly, his vision was broadly consonant with Progressive-era pioneers like John Dewey, a clear and important influence on his work. And use of the word “progressive” to describe those like him skeptical of test-driven curricula and information delivery systems is also accurate, if a bit imprecise. But “progressive” is a word that can obscure at least as much as it reveals. Sizer’s progressivism owed a lot more to, say, Jane Addams than Theodore Roosevelt. It was the bottom-up progressivism of the urban reformer, not the top-down progressivism of the elitist technocrat. His emphasis on the local and the empowerment of the individual made him a compelling figure to President George H.W. Bush, who invited Sizer to the White House to discuss his ideas, no less than President Bill Clinton, who worked with Sizer as governor of Arkansas on Re:Learning, a progressive-minded effort to launch school reform at the state level, and who summond him to visit the White House as well.

Perhaps a better term for understanding Sizer’s work is “pragmatist.” The figure most prominent in this regard is another New Englander, William James. The Jamesian faith that truth is something that happens to an idea is evident in Sizer’s famous precept that “unanxious expectation” is the optimal stance in a teacher’s relationship with a student. By acting as if a student will succeed in accomplishing a complex, independent project, you can in effect make it so: faith has catalytic power. Calling Sizer pragmatic might sound a bit odd to some, given that much of the criticism of his work centered on a belief that his ideas were impractical. This was the critique leveled at Sizer by respectful critics like E.D. Hirsch and Diane Ravitch, who long argued that a more content-based approach is ultimately the most practical one for students to make their way in the world. “Some ‘essential’ schools are a little loosey-goosey for my personal curricular taste,” another friendly critic, Chester Finn, recently wrote. “But my chief anxiety about Ted’s approach to education reform isn’t that there’s anything wrong with the schools; it’s that this approach is not easily replicated or scaled. To which he, of course, would reply that no other approach will actually succeed, at least not when it comes to delivering bona fide education (which he never confused with embedding basic skills in scads of kids).”

To the end of his days, Sizer remained relentlessly focused on what actually works—and solutions that were the product of close empirical observation at thousands of schools. He was an early champion of vouchers so that public school families could vote with their feet, a position that put him at odds with some liberals. While determinedly opposed to the Bush administration’s No Child Left Behind law of 2002, Sizer was never opposed to standards per se. What he insisted upon is that the standards for those standards be high, that those doing the evaluating did their homework no less than the students. The often unspoken appeal of standardized tests for those who champion them is the ease with which they can be administered rather than the value of what they measure. Authentic assessment is difficult; good work always is.

Moreover, Sizer understood as a matter of instinct and reflection that the search for the truth is never simply a matter of gathering information, one reason he lamented the mindless quality of so much education research and the misplaced priorities of most Ed schools. That’s why, when he tried to convey the reality of everyday school life in the United States, he did so through a fictional character: Horace Smith, the beloved teacher (and later principal) of the archetypal Franklin High. Horace lives on in the pages of Sizer’s celebrated trilogy: Horace’s Compromise (1984), Horace’s School (1992) and Horace’s Hope (1996). In capturing the granular details of the classroom, and the often painful dilemmas that prevent good people from doing their best work, Sizer both comforted and inspired hundreds of thousands of students on the road to becoming teachers.

Further Reading:

Theodore R. Sizer’s best known book is Horace’s Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School (Boston, 1984), followed by Horace’s School: Redesigning the American High School (Boston, 1992) and Horace’s Hope: What Works for the American High School (Boston, 1996). Other notable works in the Sizer canon include The Students Watching: Schools and the Moral Contract, co-authored with Nancy Sizer (Boston, 1999), and The Red Pencil: Convictions from Experience in Education (New Haven, 2004). For an anthropologically-minded critique of Sizer’s reform efforts, see Donna E. Muncey and Patrick J. McQuillan, Reform and Resistance in Schools and Classrooms: An Ethnographic View of the Coalition of Essential Schools (New Haven, 1996). See also Chester Finn’s adversarial tribute to Sizer at Flypaper, an educational blog at Fordham University.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.2 (January, 2010).

Jim Cullen, who teaches at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York, was Theodore R. Sizer’s son-in-law. Cullen’s most recent book is Essaying the Past: How to Read, Write and Think about History. He blogs at American History Now.