Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

Steaming with anger, Claude-Joseph Villars Dubreuil struck out from his plantation home on the Mississippi River one early morning in June 1748, to make his complaint before the Superior Council, the seat of government for the Parish of New Orleans and the Province of Louisiana. An original founder of the town, and its most important citizen in every sense, Dubreuil had good reason to be disgruntled. Despite his wealth and power, he had been insulted by the military police officer charged with keeping order, Major Membrède. Dubreuil regarded the man’s behavior as unendurable, the beginning of what was to become a fierce confrontation over the next three years.

All along his ride, Dubreuil saw evidence of his many contributions to the building of this still modest town, since his arrival at the beginning of its construction in 1719. His slaves had reinforced the natural levee before New Orleans, a massive project that made the town safe from floods for the next three centuries. The same slave workforce had built the governor’s residence, the charity hospital, a canal, royal vessels, a sawmill, and a fort one hundred miles below at the mouth of the Mississippi that protected the town’s approach. All of this activity had taken place under Dubreuil’s authority as contractor for the Royal Public Works. Just now, he was passing the imposing new Ursulines’ Convent, another project to which he had contributed. He could field 150 of his own slave laborers in 1748, from a total personal slave force between two and three hundred, by far the largest in a community where a force one-tenth that size was substantial. As a private entrepreneur, he had overseen the development of two major plantations at Tchoupitoulas, and had recently purchased a major plantation just below the town center. He had also been involved in the African slave trade to New Orleans, the establishment of indigo cultivation, spurge wax production, and an experiment in sugar production, to say nothing of major brick-making and timbering enterprises. If New Orleans’ isolation from the Atlantic world meant that it still had a sluggish economy in 1748, it owed what vitality it possessed to Dubreuil.

Although no nobles established themselves in Louisiana, Dubreuil was almost as exalted as a duke in his community: he far outstripped other founders by his great wealth and industrious pursuits. Supported by a distinguished family in France, he had sailed to Louisiana with a group of artisans he sponsored. With his remarkable variety of economic pursuits, he upheld a high standard of ambition and industriousness for the community. That such a man was willing to remain in such an unpromising location, and that he and wife Jeanne-Catherine La Boulaye married their children to locals, gave heart to lesser landowners and promoted entrepreneurial values. Like Claude and Jeanne-Catherine, and like Anglo-American planters in neighboring colonies, most New Orleans slave owners were committed to their patrimony in the colony, rather than thinking of themselves as temporary exiles from Europe like the West Indian planters. Like Claude and Jeanne-Catherine, most locals settled close to the town center to strengthen the capital and make it look stronger and more flourishing than it was.

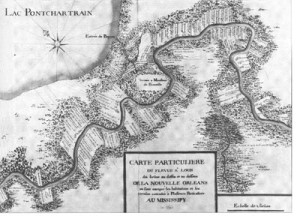

Carefully planned at its founding in 1718, New Orleans Parish spread along the turn of a major crescent in the Mississippi River. By 1748, the white population totaled about two thousand, including the founding generation of immigrants from western France and New France, and the young creole (or American-born) generation. The slave population of perhaps four thousand consisted of the survivors among several thousand Africans brought to New Orleans in the 1720s, plus their creole children and a handful of Indian slaves. The town center, which lay on the left bank at the precise turning point in the crescent, was a rectangular grid designed to be a neat, compact residential space. From it radiated directly the indigo and rice plantations. These were distributed as narrow long lots in compact fashion, stretching from frontage on the river, through the riverine sediments the planters farmed, to the swamp or forest running behind the plantations.

Most plantations were just out of shouting distance from one another, so socializing was common, and all were relatively close to the town center. Known today as the Vieux Carré, the center housed the colony’s civil and military officials and soldiers, the clergy, some artisans, barkeeps, and shopkeepers. But the great majority of slaves, free white people, and free blacks lived in the adjacent plantation regions. To the town center, white and black resorted frequently to enjoy the social life there, or to conduct affairs in one of the official institutions. Travel between plantation and town center was frequent because it was easy. From the most extreme upriver district, Tchoupitoulas, where the main concentration of slaves and planters now lived, one could reach the town center in less than an hour and a half on foot, less than half that by horse, or in minutes by water. Dubreuil lived only minutes away by horse.

The Parish of New Orleans, then, was more tightly knit than it looked on a map. It was centered by the Place d’Armes, today’s Jackson Square. Dubreuil now came upon the official establishments clustered around the square, imposing edifices that gave the town center some claim to dignity despite its tiny population. The plaza served as the weekend market, and the gathering place for religious or other festivals, military drilling, and judicial executions. On one side ran the levee that held back the river. Opposite the levee was St. Louis Church, the presbytery housing the town’s spiritual fathers (the Capuchins), and a brick jail, which had four “cells” for blacks on the ground floor and four “rooms” for whites. The army barracks flanked the two sides of the plaza. In Dubreuil’s day, those streets oriented horizontally to the river already had the social characteristics they have today: Chartres and Royal Streets were the most richly and respectably built, while Bourbon Street was already a vice zone for locals and sojourners: a place for drinking, gambling, dancing, gorging on the produce of the immensely rich environment, and prostitution. From this central terrain of social life radiated the upper and lower plantation coasts.

The town was situated precisely where it had to be to control access to the Mississippi Valley. The site benefited from centuries of Indian custom in that it lay athwart an old Indian portage between Lakes Pontchartrain and Borgne and the river, the trail that now terminated as Rue de l’Hôpital. Rather than sailing nearly one hundred miles to the Gulf of Mexico by the Mississippi, a vessel with Dubreuil’s cargo could take the backdoor route through the lakes to the gulf in two days or less. In New Orleans, Dubreuil not only farmed some of the richest sediments in North America, he lived at the exact nexus of transatlantic trade for people living in the interior of the continent west of the Appalachians. The town served as a catch basin for the produce of the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri River Valleys.

Despite the site’s wealth of natural resources, numerous irritants existed that locals either had to suffer, or to drown with copious quantities of Bordeaux or cheap West Indian rum. It was very hot and damp six months a year, it was one of the least-favored ports in the New World, and huge swarms of insects appeared seasonally with terrifying predictability. Rapid decay dominated the atmosphere. Most buildings were constructed of wood, and so were subject to rapid disintegration and fire. The elevation was so low that the dead would not stay buried: the ooze was likely to thrust them up into the daylight. The population grew slowly by New World standards and may have declined between the early 1730s and early 1740s. Their only near neighbors were a little colony of German immigrants just above New Orleans, and the little French settlements far up the Mississippi and Mobile Rivers. The passing of a great man like Dubreuil or the execution of the occasional slave were among the few diversions in this usually sleepy town.

Early New Orleans gave off a bucolic atmosphere in an isolated setting, but underneath the apparent calm on the surface lay a basic social cleavage and with it, a dangerous tension. The whites preserved their idea of order only by constant vigilance and their willingness to apply brute force to defeat slaves’ aspirations to be free. Two decades before Dubreuil’s ride, the slaves had shown signs of concerted rebelliousness, and they would do so again in 1783 and 1811. It was, in other words, a typical North American slave society in which whites organized all social life to keep slaves enslaved. Dubreuil and the other planters ultimately held the upper hand only because of their alliance with colonists in other parishes–and because they had help from the soldiers.

New Orleans was different from Norfolk or Savannah, in that it always had a garrison of two to three hundred soldiers maintained by the French Crown. These career military men provided defense against external attack and internal unrest. Off duty, the soldiers also provided casual labor to supplement their meager incomes, but they could be an affliction to the locals. This was never truer than at this moment, for two reasons. First, the people of lower Louisiana were on high alert against attack by their English neighbors, for the War of the Austrian Succession was in its fourth year. Locals knew that they had a seaport of immense strategic importance. Fortunately for them, in 1748 their geographic situation was still too difficult of access to be captured by one of the several imperial powers that hoped to command that particular bend in the Mississippi. But in 1748, of course, the people of New Orleans did not know how secure they were, and the soldiers were edgy from being on wartime alert for years without an opportunity to engage the enemy.

A second reason the soldiers were a problem for the townspeople was that they were being used by a tyrannical post commandant, Major (Chevalier) Membrède, in a scheme to milk the local economy for personal profit. Membrède set his soldiers on anyone who opposed his effort to gain a monopoly on the sale of low-grade rum to soldiers and slaves, a form of extortion that festered for years and would end with Membrède’s dismissal. (The major may have been in partnership with the governor, Pierre de Rigaud, marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial, who was notorious for soaking colonists through monopolies.) The usually placid atmosphere was poisoned by this clash between the major and leading townspeople like Dubreuil. The day before, Membrède’s soldier-police had arrested two of Dubreuil’s slaves in the night, for allegedly stealing three hundred dollars from army sergeant Marette’s quarters. As soon as he heard of the charge, Dubreuil had ordered his entire slave force to comb the town for the accused, but Membrède got to them first. The major now had the means to humiliate the planter: even if he could not force the slaves to confess to the crime, it was a personal rebuke to Dubreuil as a slave master for any of his chattels to be arrested. Everyone held their breath as the news traveled at lightning speed around a town where everybody knew everybody: Dubreuil was now going to stand up to Membrède.

The rum controversy between Membrède and civilians like Dubreuil involved a fundamental question of power: masters wanted to retain control of the distribution of rum to slaves, both by their own personal rations in the slave quarter and by civilian-controlled taverns in the sale of drams. In this contest between military and civilian authority, the civilian population had little recourse against the major’s tyranny, for they had no representative institution in which to exert their power, like the Virginia House of Burgesses. In other words, not even the richest planter like Dubreuil had a sure way to counter arbitrary military actions, except by formal appeal directly to Louis XV. On June 9, Dubreuil now tried anyway by approaching the Crown’s paid local magistrates of the Superior Council to complain.

Dubreuil probably went straight to the jail, awaited by the authorities and several of his slaves with the names Louis and Jean, the two most common male names in town, those provided by the crime’s only witness. One of the suspects named Louis was the most highly placed artisan in the colony, an eighteen-year-old Dubreuil had apprenticed in the royal hospital to become a surgeon. At the time of the crime, he was attending a woman with menstrual complications, and the nuns who served in the hospital would readily attest both to his unimpeachable character and his whereabouts. After interrogation, the procurator general (or attorney general) released him. Other slaves who had been arrested despite the fact they were named Claude and Joseph–both African-born with additional African names–also quickly passed their interrogations. They both claimed to have stayed in le camp, as locals called slave quarters. In ordinary circumstances, they might have gone to the town center in the night, but they had not that night. When interrogators finally got to suspects who knew something, they discovered that the supposed armed robbery was complicated and ambiguous.

The Louisiana-born slave Marie, twelve years old, was the only witness to the crime and may have been involved. She testified that two Dubreuil slaves she knew well–whom she now named as Joseph and Jean Gué–had broken through the window into her masters’ home, while she alone guarded the house. They took the money from an armoire, and demanded that she lie: she was to say that Bellair’s Louis and Jean had committed the crime. This was one very vulnerable child: her father was dead and her mother either belonged to or worked for another master. Marie herself was only rented by her owner Sieur Lamelle to Sergeant Nicholas Marette and his wife. The attorney general tried to get her to admit that she had stolen the money herself and given it to her mother, and then he tried to get her to say the robbers paid her for her silence. She stuck by her story.

Over the following two weeks, the authorities released all suspects, including the accused Dubreuil slaves. Like so many criminal cases in the records, the outcome of this one is not clear. The judges of the Superior Council probably agreed with Dubreuil that the accusations were groundless, and that Marie may have been the pawn of Marette and Membrède. It came out that the supposed victim Marette had only recently borrowed money to pay his debts, so how could he have had so much money to be stolen? They all knew that Marette’s superior, Membrède, had a motive to extort cooperation from Dubreuil on the rum issue by causing him shame about his slaves–a master was responsible for all his slaves’ behavior: he was supposed to be a bon père de famille. Dubreuil stood to lose not only the labor of his slaves if they were found guilty, but his dignity as a gentleman. This was, moreover, just the latest in a long series of incidents involving soldiers and citizens. In the previous year, the town watched the executioner break on a wheel a slave who had killed a soldier in a rage–for drunkenly poaching on the slave’s starling trap. In the following summer, some of Membrède’s men would resort to mere brute force in open intimidation of Dubreuil by ambushing one of his most valuable and unoffending slaves–a blacksmith for whom he had paid ten thousand livres–and beating the man so badly he could not work for months. By then, the Crown’s highest civil servant in the colony was reporting home that “the people groan and murmur” about the garrison. Even the Capuchin priests began protesting about the disorderly soldiers. The complaints were always limited, of course, by the citizens’ sense of gratitude that the king kept up the garrison: the soldiers were their first line of defense to keep the slaves in line. As a result, only in 1754 did the groaning and murmuring convince the Crown to recall Membrède to France.

Dubreuil’s predicaments were several and take us into the heart of slave society in the eighteenth century. The fact that his workers were slaves meant they had no personal rights–the law positively forbade them to defend themselves against any white person. That made them a good target for a bully with authority to use as leverage against their owner: Dubreuil dreaded the personal shame he would feel if any of his slaves was convicted of a crime. In this sense, slave society inexorably leads to disorder because the law makes slaves vulnerable. Against that disorder, Dubreuil felt a strong need for the soldiers as a local police force to overawe the slaves, even if the soldiers were a nuisance. More to the point, he especially needed the soldiers because the Crown would not allow the planters to organize their own structure of local institutional power to control the lower orders. Colonists in French and Spanish colonies were much more at the mercy of arbitrary power than their neighbors in English colonies, for they had no institution like the House of Burgesses, in which to concert their power and take primary responsibility for their society. By contrast with Virginia, Dubreuil and the rest of the citizens of New Orleans had to cope as individuals with the ambitions of the Crown’s bureaucratic and military representatives, as well as with career French soldiers who had no local loyalties.

Dubreuil undoubtedly knew when he left the house that morning that he would get no satisfaction in the Superior Council, that military power always had a superior claim in the colony. The rewards of the planter’s labor were rich, and his reputation was wreathed in glory, but Dubreuil–even he–could not call himself free. Tragically, as a master of chattels, the vulnerability of his slaves was also his own, and a jealous and unscrupulous major could make trouble for him with impunity. The planter was a special kind of slave to the system.

Further Reading: For further reading on New Orleans, see Thomas N. Ingersoll, Mammon and Manon in Early New Orleans: The First Slave Society in the Early Deep South, 1718-1819 (Knoxville, 1999); Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge, 1992); Daniel H. Usner Jr., Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Mississippi Valley before 1803 (Chapel Hill, 1992); Samuel Wilson Jr., The Architecture of Colonial Louisiana: Collected Essays of Samuel Wilson, Jr., F. A. I. A., comp. and ed. by Jean M. Farnsworth and Ann M. Masson (Lafayette, La., 1987); and Henry P. Dart, “The Career of Dubreuil in French Louisiana,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 18 (1935): 267-331.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Thomas N. Ingersoll is associate professor of history at Ohio State University, Lima, and adjunct professor of American history at the Université de Montréal. Besides a book and several articles on early New Orleans, he has written a forthcoming book (2004) on Indian mixed bloods in early North America.