In December 1763, following years of grisly frontier warfare, armed settlers in the Paxton Township exacted revenge on an isolated, unarmed Indian settlement, attacked the Lancaster jailhouse where refugees had taken shelter, and vowed to march all the way to Philadelphia. While these “Paxton Boys” were stopped in Germantown by a delegation led by Benjamin Franklin, their critics and apologists spent the next year battling tooth and nail in print. Waged in pamphlets, political cartoons, broadsides, and correspondence, the ensuing pamphlet war featured some of Pennsylvania’s preeminent statesmen, including Benjamin Franklin, Governor John Penn, and Hugh Williamson, who would later sign the U.S. Constitution. At stake was much more than the conduct of the Paxton men. Pamphleteers used the debate over the actions of the Paxtons to stake claims about peace and settlement, race and ethnicity, and religious conflict and affiliation in pre-Revolutionary Pennsylvania.

In 2013, the McNeil Center for Early American Studies sponsored a two-day 250th anniversary conference on the Paxton Boys, from which Early American Studies published a special issue last spring. Despite this resurgence of scholarly activity, we’ve arrived at something of a consensus: This is a story about backcountry settlers motivated by Indian-hating, racism, and fears for personal security. That story isn’t wrong, but it also isn’t complete.

The Paxton incident was larger than the intentions of the Paxton Boys. It sparked a pamphlet war that encompassed some of Pennsylvania’s leading statesmen and comprised as much as one-fifth of the colony’s printed material. The trouble is that scholars only have access to a sliver of that material. The Paxton canon, as we know it today, is no canon at all—it’s a silo.

I discovered the Paxton pamphlet war by way of the 60-year-old edition that graces just about every bibliography: John Raine Dunbar’s The Paxton Papers (1957). I approached the Paxton massacre as neither an historian nor a Philadelphian. (I study early American literature in New York.) But, as Edward White, James Myers, and Scott Gordon have demonstrated, these records present a bounty for literary scholars eager to explore their diverse forms and idiosyncratic rhetorical techniques. Dialogues and epitaphs, poems and songs, farces and satires. Evocations of “Christian White Savages,” “A troop of Dutch Butchers,” and “the Quaker unmask’d, with his Gun upon his Shoulder, and other warlike Habiliments.” However, as I began to dig deeper into the Paxton crisis, I came to appreciate how much of the incident isn’t accessible in Dunbar’s edition and cannot be evaluated within the narrow frame of the pamphlet war.

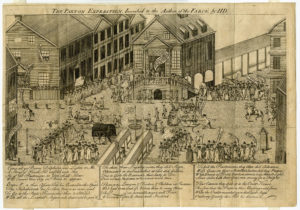

Consider the engraving “Franklin and the Quakers,” available in the Library Company’s political cartoon collection. At the forefront of this raucous scene is Benjamin Franklin, clutching a sack of “Pennsylvania money,” remarking that he’s content as long as he wins the election. Franklin’s fingerprints are all over the Paxton debate, from his Narrative of the Late Massacres, which provided a template for subsequent critiques, to Cool Thoughts on the Present Situation, which offered one of the most influential arguments for royal government. The presence of assemblyman Joseph Fox—depicted here with the head of a fox—can be understood in the context of the Assembly’s push for royalization. But the engraving also raises questions for which the pamphlets provide no context. What is Israel Pemberton doing cavorting with the Native American woman? And why is a Quaker dispensing tomahawks from a barrel bearing his initials? To understand this cartoon’s visual coding, the reader must look beyond the pamphlet war to the physical one preceding it.

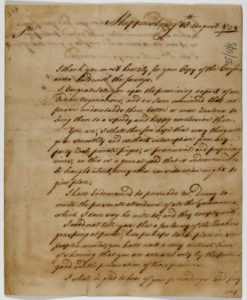

In an August 1758 letter available in Haverford’s Friendly Association papers, General John Forbes anticipates the Quakers’ public relations woes. Writing to Israel Pemberton, a leader of the Friendly Association, Forbes tempers his praise for the “promising aspect of our Indian negotiations” with a note of caution: “I need not tell you that a Jealousy of the Quakers grasping at power has perhaps taken place in some people’s minds; you have now a very critical time of showing that you are actuated only by the publick good and the preservation of those provinces.” That fall, Pemberton and his allies did succeed in their negotiations. At the Treaty of Easton, the Pennsylvania government promised to respect the autonomy of Ohio country Indians in return for their cessation of attacks on settlements. But the Friendly Association’s influence was short-lived. After 1758, the Pennsylvania government began negotiating directly with Ohio country Indians. Attacks continued, and later increased with Pontiac’s War in 1763. Backcountry settlers—as well as many sympathizers in Philadelphia—increasingly regarded all native peoples as enemies, and the Quakers their abettors.

Neither the Library Company’s political cartoon nor Haverford’s manuscript are included in Dunbar’s edition. Nor should we expect them to be. Dunbar was bound by the form of his medium. Tallying 400 pages, The Paxton Papers is already a formidable print edition, and one which continues to support research. But what else might we choose to include in twenty-first-century Paxton Papers? What if we weren’t bound, as Dunbar was, by the constraints of the codex format?

The answer may not be a definitive edition for the Paxton event, so much as a tool with which contributors may magnify and telescope records, juxtapose them against one another, read them against contexts, and discover new ways of looking at—and beyond—the 1764 pamphlet war. This is the guiding idea behind Digital Paxton.

I built Digital Paxton using an online publishing platform called Scalar. I chose Scalar over other digital collections platforms such as Omeka because it supports sequences or “paths” of content. This appealed to me because I study narratives: I love stories, and I want to provide on-ramps that promote contextual reading even as I allow visitors the opportunity to get lost in the archive. To that end, when you visit Digital Paxton—which you can do from your desktop or your smartphone—you’ll automatically enter the introductory path.

This path provides an overview of the site and guides you through some historical contexts before it deposits you in the archive. Similar to a book, Digital Paxton has an index and a table of contents. You can skim ahead by clicking the arrows associated with each section. At the bottom of every page, visitors can examine the version history, and I’ve also enabled the Hypothes.is plugin, which readers can use to create and share annotations.

Unlike a book, however, Digital Paxton is boundless, accommodates multimedia, and is fully searchable. In fact, readers can search by title or description or select all fields and metadata to search across full-text transcriptions. I’ve configured transcriptions so that they automatically overlay as annotations when a visitor cursors over the top-left corner of the image. Finally, every asset includes rich metadata collected from archival contributors, which means that visitors have everything they need to locate original materials.

In place of Dunbar’s single-author introduction, Digital Paxton relies upon five concise introductory essays, each intended to magnify a particular aspect of the Paxton massacres and print debate. After my overview, Kevin Kenny frames the Paxton massacres as both bloody and symbolic acts. In slaughtering Conestoga on government property, the Paxton Boys repudiated William Penn’s “holy experiment.” Kenny’s essay, which provides an abstract of his argument in Peaceable Kingdom Lost (2009), was the first I solicited because I wanted an essay that would foreground the role of Quaker settlement practices in the Paxton debate. After Michael Goode’s concise overview of Pontiac’s War (an excerpt of an essay that originally appeared in The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia), Jack Brubaker, author of the Massacre of the Conestogas (2010), provides a granular account of the Paxton expedition drawn from magistrates, colonial record books, and correspondence—some of which are available in Digital Paxton. Darvin Martin complements Brubaker’s work by historicizing the site of the first massacre, Conestoga Indiantown. Far from some random target, Conestoga Indiantown occupied a central place in Native American-colonial relations in the eighteenth-century mid-Atlantic.

Each essay is edited to ensure that it’s thesis-driven, jargon-free, and accessible to a precocious high school or undergraduate student. At the same time, each piece maintains the features of a scholarly essay: a bibliography of secondary research, attribution of primary source materials, and contextual notes where relevant. I’ve also edited essays to ensure that they’re self-contained. That is, if a reader were only interested in the history of Conestoga Indiantown, she could read Martin’s essay, use its links to explore the Digital Paxton archive, and perform additional research using the two dozen linked resources listed below further reading. Martin’s essay is also exemplary because it leverages tags to connect visitors with additional contexts.

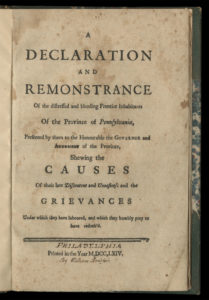

In a final overview essay I consider the Paxton debate as a political crisis of representation that culminates with the Northwest Ordinance, which both conceptually and practically resolved many of the grievances that the Paxton Boys enumerated in A Declaration and Remonstrance. (This pathway began as a digital companion that reproduced and extended an exhibition I created in close collaboration with Jim Green, librarian at the Library Company of Philadelphia, and Michael Goode, assistant professor at Utah Valley University.) Historians such as Patrick Griffin and Peter Silver have already placed the Paxton debate in a revolutionary lineage. Extending that lineage to include the Northwest Ordinance allows us to see the American Revolution as a continuation rather than a resolution of colonial debates about race and ethnicity, political representation, and settlement practices. Finally, placing the 1764 pamphlet war in a lineage that extends from the Seven Years’ War to the Northwest Ordinance opens up the Paxton crisis to those who might not otherwise know about it. If the backcountry is often treated as a massive negation in early American history, the Paxton expedition forces us to confront that absence—backcountry settlers literally march to Germantown. By reading an ostensibly urban debate about Paxton conduct alongside correspondence, journal entries, and diaries available at regional archives, scholars and educators can de-emphasize urban polity and introduce students to archival research.

Digital Paxton will continue to grow through Scalar paths. To provide theoretical and historical entry points to the Paxton print war, the site relies upon conceptual keyword essays. Modeled upon the work of Raymond Williams, and more recently Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler, these keyword essays provide conceptual and interdisciplinary approaches to the Paxton corpus. Similar to a historical overview essay, each keyword is edited to ensure that it’s accessible to undergraduate students, yet retains the research of a traditional journal article. In fact, all five of the essays develop or extend arguments that authors originally pursued in books or journal articles. The key difference is that each essay historicizes or theorizes a keyword from the Paxton print war. Today, those include James P. Myers Jr.’s “Anonymity,” Benjamin Bankhurst’s “Anti-Presbyterianism,” Nicole Eustace’s “Condolence,” Scott Paul Gordon’s “Elites,” and Judith Ridner’s “Material Culture.”

One feature of the Dunbar papers that I would like to translate to Digital Paxton is chronological and argumentative sequencing. I’ve made all manuscripts accessible as a chronological sequence, and I want to do the same for broadsides, political cartoons, and pamphlets. Digital Paxton already includes optional paths for visitors interested in the Friendly Association, multiple editions of pamphlets, and German-language materials. I’m eager to add additional paths that surface intertexuality, edition changes, and exchanges between Paxton critics and apologists.

The boundaries between Digital Paxton the critical edition and Digital Paxton the archive are porous. While I began this project by seeking to create a more expansive critical edition that would reflect contemporary historiography and scholarship, I’ve come to prize the project’s vast and varied archival resources. In this sense, I align with Jennifer Keith, who argued earlier this year at the Modern Language Association that digital editions are most effective when they include digital archives (“Extending and Expanding Our Consideration of the Digital Scholarly Edition“).

Today, Digital Paxton includes 1,605 pages of material: that makes it roughly four times as expansive as the Dunbar Papers. Every image is print-quality (300 dpi or higher) and available under Creative Commons licensing. The archive features eighty-two manuscripts, sixty-five pamphlets (including the twenty-eight identified in Dunbar), twelve broadsides, seven political cartoons, and eleven artworks such as paintings, sketches, and maps. At present, Digital Paxton has about four dozen full-text transcriptions, a number that ticks up each week. (I try to add a new transcription every week.)

While the core archival material was digitized by the Library Company and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, I’ve solicited materials from both large and small archives, including the Library of Congress, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, the American Philosophical Society, and the Moravian Archives of Bethlehem.

The APS alone has contributed more than two dozen rare holdings, including Ben Franklin correspondence, rare editions of broadsides and pamphlets, and a dazzling array of letters from Lancaster’s chief magistrate, Edward Shippen. Meanwhile, the Moravian Archives, the kind of small regional archive that scholars might otherwise overlook, has digitized archival records that were previously only available in print. In both instances, Digital Paxton makes publicly available materials that aren’t available elsewhere, a boon for researchers and, hopefully, the institutions that contribute to the project.

Let me be clear: I do not envision Digital Paxton as a substitute for traditional archival research. Quite the opposite. My hope is that Digital Paxton will surface materials that students and scholars might not otherwise know about, and encourage them to visit print archives. To that end, every digital asset includes the information a visitor would need to retrieve the original: the name of its parent institution, a call number, and relevant collection information. I’m convinced that there is no substitute for working with material objects, and, perhaps more importantly, I’ve benefited immeasurably by working with archivists. Digital Paxton doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and I’m eager to connect it with other digital resources. For example, on the path that I’ve created to showcase Friendly Association manuscripts, I’ve also added a description and link to Beyond Penn’s Treaty, a digital project from Quaker & Special Collections at Haverford and the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore. I also plan to add a page that highlights the Lenape Talking Dictionary.

This brings me to one area where Digital Paxton is very much a work-in-progress: indigenous materials and perspectives. It’s said that history is written by the victors; it’s less often appreciated that archival materials are assembled by them as well. Digital projects often translate existing forms of social bias into a new medium, rather than taking the opportunity to rethink those biases and produce a more just form of historical documentation.

While I’ve tried to select Friendly Association correspondence that gives voice to native negotiators, many of those letters are mediated through colonists. They also largely predate the Paxton massacres. Even if we cannot find native accounts of the Paxton massacres and expedition, I’m eager to add contemporary perspectives that would signpost archival silences. In the words of Rodney Carter, “The naming of the silence subverts it, draws attention to it.”

Darvin Martin’s essay on the history of Conestoga Indiantown is a start, but only a start. However, one virtue of a digital archive is that we can add contexts as they become available. Furthermore, those contexts needn’t be print materials: with support for audiovisual content, Scalar is more hospitable to oral records than traditional archives.

Digital Paxton uses distortion—especially gaps—to subvert a sense of definitiveness. For example, the site does not include Israel Pemberton’s response to the Forbes letter I quoted earlier. This isn’t because the Pemberton response isn’t valuable, but rather because I want visitors to understand, and to grasp, experientially, the limits of the archival project.

Here I confront a tension within the structure of Digital Paxton: this may be a project built around stories, linear sequences of content, but I don’t want visitors to get too comfortable in those tracks.

In their work with African American and Chicana/o literature, Dana Williams and Marissa López have advocated for an ethnic archive that serves as a contestatory site that upends the idea of single truths and seeks cacophony rather than harmony. While Digital Paxton eschews cacophony (at least by design) it does aspire to what feminist historian Adele Perry calls polyvocality. In layering materials and contexts, I want to render each less definitive, more partial, contingent, and subject to scrutiny.

The digital edition affords a capaciousness that isn’t feasible in codex. There’s no reason Digital Paxton can’t grow to three times its current size, and the contents of that archive needn’t be textual: in addition to images, Scalar supports a variety of audio and video formats well-suited to the aural tradition. At a technical level, then, the platform is prepared to support the philosophical goals articulated by the editors of the Yale Indian Papers Project: the archive as common pot, a “shared history, a kind of communal liminal space, neither solely Euro-American nor completely Native.” This, I think, is the allure of the digital: to produce not only a common pot, but a common cauldron that embraces and elevates new material forms, voices, and perspectives on historical records.

Further Reading

Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler, eds., Keywords for American Cultural Studies (New York, 2014).

Rodney G.S. Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence.” Archivaria 61 (2006): 215-233.

Paul Grant-Costa, Tobias Glaza, and Michael Sletcher, “The Common Pot: Editing Native American Materials.” Scholarly Editing: The Annual of the Association for Documentary Editing 33 (2012): 1-17.

John Raine Dunbar, ed., The Paxton Papers (The Hague, 1957).

Scott Paul Gordon, “The Paxton Boys and Edward Shippen: Defiance and Deference on a Collapsing Frontier.” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14.2 (2016): 319-347.

Patrick Griffin, American Leviathan: Empire, Nation, and Revolutionary Frontier (New York, 2007).

Kevin Kenny, Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn’s Holy Experiment (New York, 2009).

James P. Myers, The Ordeal of Thomas Barton: Anglican Missionary in the Pennsylvania Backcountry, 1755-1780 (Bethlehem, Penn., 2010).

Alison Olson, “The Pamphlet War over the Paxton Boys.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 123.1/2 (1999): 31-55.

Adele Perry, “The Colonial Archive on Trial: Possession, Dispossession, and History in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia.” Archive stories: Facts, fictions, and the writing of history (2005): 325-350.

Peter Silver, Our Savage Neighbors: How Indian War Transformed Early America (New York, 2008).

Edward White, The Backcountry and the City: Colonization and Conflict in Early America (Minneapolis, 2005).

Dana A. Williams and Marissa K. Lopez, “More Than a Fever: Toward a Theory of the Ethnic Archive.” PMLA 127.2 (2012): 357-359.

Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. (New York, 2014).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4 (Summer, 2017).

Will Fenton is the Elizabeth R. Moran Fellow at the American Philosophical Society, PhD candidate in English at Fordham University, and creator of Digital Paxton. His dissertation explores how nineteenth-century American novelists use “fighting Quakers” to authorize the violences attendant upon settlement, slavery, and nation-building.