Moraley purchased a three-penny loaf of bread at John Bryant’s bakery, a structure measuring 23 feet wide along High Street and stretching 72 feet in depth along Latetia Court. Francis Richardson, clockmaker and goldsmith, rented a shop next door, and Moraley, trained as a clockmaker, stopped in to see if Richardson might be interested in purchasing his indenture. As Moraley learned, Peter Stretch was the “eminent” watchmaker who dominated the profession in the city. Arriving in 1702 at the age of thirty-two, Stretch produced dozens of tall-case clocks that provided refinement to the homes of the affluent. Stretch was also prominent politically and religiously, serving for thirty-eight years as a city councilman and participating in Quaker affairs. However, where Stretch succeeded materially and socially, Moraley would fail. Moraley arrived in the city at an inauspicious time for men in his occupation since the number of clockmakers exceeded the local demand for their products. It was a prime reason why he was sold last among the group of servants with whom he arrived. It also proved a critical factor in Moraley’s subsequent struggle with unemployment and poverty once he gained his freedom.

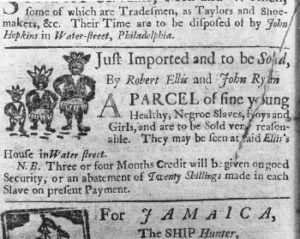

Another ingredient necessary for artisans to realize success was access to capital to enable them to establish their own shop. In the next block of High Street, John Frost, a newly freed servant, began a partnership with Thomas Carter, renting a shop where they could sell the stays and coats they manufactured. Benjamin Franklin, whose printing office was nearby, illustrates the difficulty that many journeymen encountered. He agreed to collaborate with Hugh Meredith, an alcoholic with few printing skills, primarily because Meredith’s father financed the business. Franklin subsequently borrowed from his friends and even bargained for a marriage, if the dowry was sufficient to pay off his debt and establish him as an independent master printer. When the proposed dowry proved inadequate, Franklin declined the marriage. While many merchants like Edward Horne and some artisans like Stretch and Franklin could take advantage of the rapid economic development of the Delaware Valley, others, like Moraley, were unable even to survive financially, much less prosper.

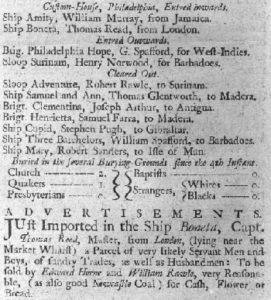

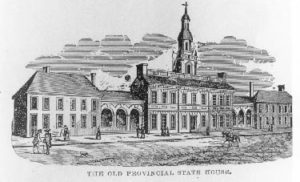

Continuing along High across Second Street, Moraley paused to read some of the official notices–including new acts of the assembly, announcements of the assize (price) of bread, and broadsides of market regulations–posted on the courthouse in the middle of the market. One pressing political issue when Moraley arrived was the amount of paper currency the colony should print, and brochures about the topic were nailed to the courthouse. As in most British colonies, currency was scarce since the balance of trade favored Britain. Pennsylvania emitted £30,000 in 1729, and the funds were used, in part, to enable farmers to borrow against their land and to pay public officials. The amount of money in circulation concerned many Pennsylvanians since it helped shape the economy. Franklin had recently penned an anonymous pamphlet advocating a liberal paper money policy, and Moraley would write about the topic in his autobiography as well.

Criminals sometimes suffered public punishment at the courthouse, often on market days when a great number of people could watch. Six months after Moraley’s walk, according to the Pennsylvania Gazette, Richard Evans “received 39 Lashes at the publick Whipping-post, having been convicted of Bigamy.” A few weeks later, “Griffith Jones, and one Glascow an Indian, stood an hour in the Pillory together, and were afterwards whipt round the Town at the Carts Tail, both for Assaults with Intent to ravish” a woman and young girl. Five days after Moraley passed the courthouse, a jury sitting there found two servants, James Mitchel and James Prouse, guilty of stealing seven pounds (equivalent to three months income for a day laborer) from a barber’s house in Front Street. The judge sentenced them to death for a crime of such an “enormous Nature.” A month later, a large crowd gathered at the prison (at the west end of the market) “to see these unhappy young Men brought forth to suffer.” They were placed in a cart, “together with a Coffin for each of them,” and carried to “the fatal Tree” for hanging. At the last minute, with the ropes around their necks, the governor spared their lives with a pardon, thereby pleasing not only Mitchel and Prouse but also the “common People, who were unanimous in their loud Acclamations of God bless the Governor for his Mercy.”

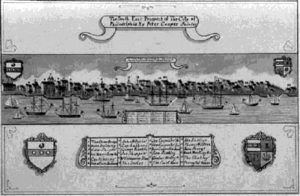

The butchers’ shambles, where animals were slaughtered and sold on Sundays, abutted the courthouse. Moraley strolled along this smelly, fly-infested market, past Strawberry Alley and White Horse Alley. In 1682, William Penn had planned a “greene countrie towne” comprised of immense houses situated on large lots surrounded by orchards, which he expected would expand rapidly westward. However, Philadelphians soon ignored the design, instead carving up the grand blocks with numerous alleys and congregating densely along the Delaware River, the economy’s lifeline. William Stapler, tin man, peddled small metal goods in his store along High Street. Next door, shopkeeper John Le sold diverse items imported from London, ranging from diapers and tablecloths to gunpowder and snuff.

Members of the First Presbyterian Church adjacent to Le’s shop may have purchased some of their Bibles from him. The continual arrival of Scots and Scots-Irish immigrants expanded the Presbyterian congregation, which accounted for roughly one of every ten Philadelphians. William Penn’s liberal policy of toleration had encouraged settlement by people with various religious beliefs. Anglicans were the most numerous in the city, with Quakers a close second. Baptists, Swedish and Dutch Lutherans, Dutch Calvinists, and a handful of Catholics also worshiped there. African slaves practiced their own beliefs as best as they could. The medley of tongues that Moraley heard near the market matched this diversity of religions. Besides English, Dutch, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Gaelic, Philadelphians spoke a host of African and Native American languages. Indeed, Christ Church, the Anglican house of worship currently under construction, would hold sermons in “Welch” as well as English.

Across White Horse Alley on High Street was the Sign of the Conestoga Wagon, where the proprietor kept “good Entertainment for Man and Horses at reasonable rates.” Its “large Yard Room for Waggons and Cattle” made it a convenient place “for Killing and Dressing of Hogs” to be sold across the street at the shambles. Farmers often stayed there when bringing their livestock to market. A few paces further, Moraley came to the Sign of the Indian King, a prominent public house run by Owen Owen, a former city sheriff. The inn offered both lodging and alcohol. About one hundred licensed taverns–approximately one for every seventy-five residents–served a very hard-drinking population in the city. The Indian King was a substantial structure. It contained eighteen rooms, fourteen of which had fireplaces, a large brick kitchen, and a two-story stable that would accommodate one hundred horses and fifty tons of hay. The Society of Ancient Britons met there for a feast each year before attending the Welch sermon at Christ Church.