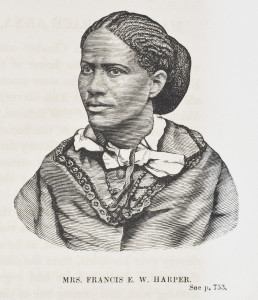

Before delving into the rediscovery of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s long-lost first collection of published poetry, Forest Leaves, my contribution to this roundtable comes with a disclaimer: I’ve had the pleasure of working with Johanna Ortner as a graduate student in the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and I’ve had some difficulty parsing my enthusiasm about this discovery from the excitement that comes from seeing students making real and valuable discoveries in the archives through the process of primary research. That said, the rediscovery of Forest Leaves is surely an important one all on its own, one that will draw attention to Harper’s early life in Baltimore, to her craft and meticulous revision process across her career, and to the contours of African American women’s authorship in the nineteenth century. In what follows, I want to explore Harper’s striking resistance to nostalgia in Forest Leaves, especially exemplified by her refusal to endow her meditations on childhood and youth with sentiments of reverie or innocence. At the root of Harper’s anti-nostalgia is an understanding that any look to the past in the antebellum United States is simultaneously a look to the slave past. I go on to think about what lessons Forest Leaves might offer to scholars, especially given the recent turn, or more properly, return to the archive in African American literary studies. Forest Leaves—a text that contains both tantalizing glimpses of origin stories and past recoveries—is also precisely the text that can warns us about the dangers of nostalgia for particular origins, or clear genealogies, in recovery work around early African American literature.

Schoolwork, Aesthetic Work, Public Work

How do we begin to understand Harper’s “leap” into print in the late 1840s or possibly, as Carla Peterson indicates, in the early 1850s, when the poet was in her twenties? The intertextuality of the poems as well as their careful curation within the volume points to a young Harper’s interest in addressing a public, or possibly multiple publics. And while the poems do traverse a range of themes and disciplinary subjects, they do not seem beholden to the demonstration of knowledge that marks nineteenth-century schoolwork productions. In other words, these are not schoolhouse verses: they display a poet who has already established a strong poetic voice and a set of clear aesthetic and political commitments that continue to be reflected in subsequent published works, especially in her other antebellum pamphlet collections that Meredith McGill calls Harper’s chapbook poetry.

At the same time, Forest Leaves does bear some of the traces of Harper’s schooling, her religious education, and her experiences as a young, nominally free woman of color growing up in Baltimore. Harper’s uncle, the preacher, activist and educator William Watkins, looms large in the story of the poet’s upbringing since he served as both an adopted father and schoolmaster. Melba Boyd notes that Watkins was largely an autodidact who taught himself English language and literature, Greek, Latin, and even medicine. At the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth, Harper was immersed in a curriculum that focused on the study of the Bible, but also history, geography, mathematics, English, rhetoric, and oratory, among other fields. Boyd notes that at Watkins’s school, composition was an almost daily activity, and it is likely that this intensive practice of writing and rhetoric shaped the precision and control displayed in her poetry. The woods and nature also served as a type of classroom for the burgeoning poet, who, according to Theodora Williams Daniel, “frequently visit[ed] the woods where she listened to the birds and gathered leaves tinted by the sun in order to stimulate her imagination.” In addition to spending time in nature, Harper also learned natural history and natural philosophy at her uncle’s school. Harper’s poetry was thus shaped by the disciplinary and learning structures of formal schooling, but also by forms of learning and auto-didacticism in the parlor as well as “in the field.” We might also think about the city of Baltimore as an important laboratory space for the development of Harper’s thinking about the complexities of race, gender, slavery, and the precariousness of freedom for African Americans in the antebellum period.

For my own research on African American engagements and experiments with natural science in the antebellum period, I am interested in thinking more about Forest Leaves’s relationship to black women’s manuscript cultures and compositional practice in the antebellum period, especially as they reflect the study of natural history among free African American women. Just as the title of Forest Leaves plays with the connection between “leaves” in the forest and the leaves of her book, black women’s friendship albums from the period connected “poesy” to “poesies.” These sentimental albums paired floral-themed verse with paintings of flowers, included natural history lessons on flora, and also served as part-herbariums, offering up a number of floral specimens in painted form. Looking ahead to 1855, Walt Whitman would also reflect on the intertwined materiality of writing, print, and nature in Leaves of Grass, a title that resonates with that of Forest Leaves.

Harper All Grown-Up

At least at this preliminary stage, I’m thinking about Forest Leaves as a transitional volume: a collection that reflects Harper’s youth and schooling, but that is also already attuned to the fleeting nature of life, to the moral stain of slavery on the nation, and to many other “grown-up” topics. This is a youthful production, to be sure, especially reflected, as Ortner points out, in the poems that address romance and budding sexuality. But as much as Forest Leaves reflects the sentiments of the young, it also feels like the writing, please excuse the cliché, of an old soul. The pamphlet is filled with poems about illness, death, and looking for peace granted by Christ at the end of one’s life. This is not a collection that looks back lovingly to the days of childhood, and the poet does not seem to have any particular attachment to the past. This striking lack of nostalgia for the days of “childhood innocence” recurs across Harper’s subsequent poetry. For example, in “Days of My Childhood,” printed in the Anti-Slavery Bugle in 1860, the desire to return to the joys and carefree nature of childhood are replaced with “holier hopes” of meeting Christ in death:

Days of my childhood I woo you not back,

With sunshine and shadow upon your track,

Far holier hopes in my soul have birth,

Than I learned in the days of my childish mirth.

Of course, Harper’s biography suggests concrete reasons for not wanting to return to the “days of my childhood.” The poet was orphaned at the age of two and her early letters frequently convey a deep sense of isolation and loneliness. But beyond these biographical details, Harper’s resistance to sentimental reveries about childhood also connects to her political vision: sentimentalism may be mobilized for abolition, but for her, its attendant nostalgia just isn’t productive for the antislavery cause.

Already here in Forest Leaves, we can see something deliberately anti-nostalgic at work in Harper’s poetry. The poet regularly looks back to the past, but she never desires a return to it. As the previously unknown poem, “The Presentiment,” opens:Foley

There’s something strangely thrills my breast,

And fills it with a deep unrest,

It is not grief, it is not pain,

Nor wish to live the past again.

Harper’s disinterest in returning to the past is clearly part of her belief in Christian redemption and the resurrection. It is possibly also a meditation on what Robin Bernstein has identified as the construction of “racial innocence” around white children simultaneous with the exclusion of black children from the category of childhood itself in the nineteenth century. But I want to suggest that Harper’s anti-nostalgia is also about what it means to look to the past in a slave-holding nation. For Harper (as for all antebellum Americans), to look to the past, to look to the “days of my childhood,” is also to look to the time of slavery. “Yearnings of Home,” another previously unknown poem in Forest Leaves, bears a title that promises to indulge in reveries about the past. Sure enough, “Yearnings for Home” voices a wish to return home once more to feel the “native air” and to die in the presence of family. But crucially, the poem expresses a yearning to return only to the place and geography of childhood, not to the time of it. Here, in the years before she joined the Abolitionist movement, a young Harper is already suggesting that black people only have one option: to keep moving forward, even if the prospects for freedom seem dim. The (slave) past is not a place to which to return or retreat.

Harper’s Lessons

I wonder if Forest Leaves’s unsettling of convenient origin narratives might also pose a challenge to scholars of African American literature, especially those engaged in recovery projects. In light of recent scholarly conversations and publications, I have been wondering about the limits of scholarly narratives produced around recovery, especially in the archives of slavery and nominal freedom. More specifically, I have been thinking about how the editorial imperative to introduce and promote newly recovered texts at times produces critical narratives that may not enable the most generative or even accurate scholarship on such texts. For example, the claiming of “firstness” for the African American novel has produced all kinds of confusions, errors, and obfuscations (of, for example, the literary productions of black women writers). Might recovery narratives begin to tell different stories, beyond problematic origin narratives, and beyond presumptions that the significance of recovered works is always transparent, obvious, unquestionable? For example, in the case of Forest Leaves, is there a way to capture the significance of Harper’s first book of poems without relying on the supposedly inherent importance of firstness, or following Kinohi Nishikawa’s recent essay, without relying on the tautological assumption that a recovered work of literature is important because it was recovered? Moreover, how do we read an object of the early black print sphere that was published, but did not circulate widely, if at all? How should scholars talk about published works that were not circulated? Like manuscripts? In the terms of counter-publics? Nishikawa suggests that we should be also thinking about the condition of “lostness” of recovered texts, rather than seeking recognition for such works by immediately incorporating (re)discovered works into a pre-determined canon, and its associated scholarly narratives. In the words of Leif Eckstrom, how do we know that we even know how to read a work like Forest Leaves?

Despite these qualifications and provocations, the recovery of Forest Leaves points to the ways that recovered works can fundamentally transform our understanding of an author’s known oeuvre. As Ortner mentions, because Forest Leaves contains early versions of well-known poems, we must now understood those poems as revisions of earlier works. This is really a modest understatement by Ortner since her rediscovery of Forest Leaves means that future readings and analyses of these poems will now have to account for the changes made between their appearance in Forest Leaves and in subsequent publications. In this way, we see that origins do matter. At the same time, the embeddedness of Harper’s poetry in schoolwork and composition, the discovery of Forest Leaves in print rather than manuscript form, and the importance of revision for Harper, all unsettle Forest Leaves as the origin of Harper’s poetry. The primacy of revision in Harper’s poetic practice further relates back to Harper’s own refusal of nostalgic origin stories, and to her understanding that a backward-looking poetry—or even a look back to one’s own poetry—is only as good as what it might enable in and for the future.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Carla Peterson, Eric Gardner, Kinohi Nishikawa, Leif Eckstrom, Anna Mae Duane, and Paul Erickson for valuable feedback and assistance with this response piece, as well as to Johanna Ortner for her discovery and work on this project.

Further Reading

My thoughts on Harper’s early life and relationship to childhood have been largely inspired by Frances Smith Foster and Melba Boyd’s foundational studies. See Foster, A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (New York, 1990) and Boyd, Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E.W. Harper, 1825-1911 (Detroit, 1994). Rather than viewing her writing as “all of a piece,” Meredith McGill focuses on the important discontinuities of Harper’s poetry over time, especially between the earlier volumes of poetry that were printed as pamphlets or “chapbooks,” and the poet’s late nineteenth-century volumes that appeared as handsome, cloth-bound books. Forest Leaves certainly does not suggest an aesthetic sensibility that can be traced continuously across all of her poetry, but it does reflect important connections between her first book of poems and her other pamphlet-printed collections, especially Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, which was first published in 1854. On the importance of the pamphlet format in the study of Harper and nineteenth-century poetry more generally, see McGill, “Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and the Circuits of Abolitionist Poetry,” Early African American Print Culture, ed. Lara Langer Cohen and Jordan Alexander Stein (Philadelphia, 2012). On the schooling of American women, including some African American women, in the post-Revolutionary and antebellum U.S., see Mary Kelley’s Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic (Chapel Hill, 2006). Kim Tolley’s The Science Education of American Girls: A Historical Perspective (New York, 2002) is also an excellent resource on the place of natural science and natural history in the classrooms of nineteenth-century girls and young women. For more on antebellum black women’s friendship albums, see Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (New Haven, 2008) and Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York, 2015). The friendship albums of Amy Matilda Cassey, Mary Anne Dickerson and Martina Dickerson are available in the holdings of the Library Company of Philadelphia and digitally at the Cassey & Dickerson Friendship Album Project. On the pitfalls of common recovery narratives surrounding twentieth-century African American literature, see Kinohi Nishikawa, “The Archive on Its Own: Black Politics, Independent Publishing, and The Negotiations,” MELUS 40:3 (Fall 2015): 76-201. My citation of Leif Eckstrom comes from personal correspondence. On the politics of recovery in the study of slavery and freedom, see the forthcoming special issue of Social Text, “The Question of Recovery: Slavery, Freedom, and the Archive” 33:4 (2015).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.2 (Winter, 2016).

Britt Rusert is assistant professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and visiting assistant professor of English at Princeton University. Her book, Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture, is forthcoming from New York University Press.