Major Sullivan Ballou’s last letter home has become something of a sacred text. Penned days before the first major battle of the American Civil War, the major’s words enjoyed an outsized afterlife when they became part of Ken Burns’ immensely popular documentary The Civil War. Read by Paul Roebling and paired with “Ashokan Farewell,” Burns created an indelible scene. Ballou, an officer in the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Regiment, used soaring rhetoric to anchor his devotion in country and family. He declared his love for his wife Sarah “deathless,” bound by cables that “nothing but Omnipotence could break.” Yet his love of country came over him “like a strong wind” and moved him inexorably to the battlefield. Burns concludes the stirring segment by relating Ballou’s sad fate: mortally wounded at the Battle of Bull Run. But his story did not end there.

Ballou’s body, buried in late July 1861 at Sudley Church near the Bull Run battlefield, did not rest in peace. Sometime after the battle, rebel soldiers dug up the remains of United States troops. According to local Blacks who witnessed the scene, the Confederates first searched for buttons as souvenirs. Their work then turned far more macabre. They started collecting bones. One soldier proclaimed that he intended to use a skull as a “drinking-cup on the occasion of his marriage.” Bull Run initiated many a soldier into the bloody world of combat. Horrified and exhilarated by the encounter, they transferred their mixed emotions into the collection of objects with violent histories. However terrible these acts, Sullivan Ballou suffered a worse fate: Confederates disinterred, beheaded, and then burned his corpse.

Ken Burns never related the fate of Sullivan Ballou’s body. To do so would have spotlighted an uncomfortable part of Civil War history marked by violence and brutality. Perhaps the master documentarian should not be faulted. The incident, well-publicized during the war years, has largely been forgotten. Simon Harrison, one of the few scholars who has written about the collection of bones in war, maintains that the “Confederate soldiers and their supporters who collected Northern skulls did so because their political interests were predicated on representing Southerners and Northerners as two different peoples.” Harrison’s argument is convincing. But the incident also speaks to a broader cultural shift. The existential crisis of civil war challenged, though never overturned, the nineteenth-century’s prevailing culture of romanticism. Soldiers’ reports from the front, citizens’ encounters with the aftermath of battle, and the circulation of objects with violent histories created narratives of war that were marked departures from conventional accounts of war grounded in heroism and glory. Only by placing Ballou’s sentimentalist letter in tension with his dismembered body can Civil War Americans’ layered discourse be fully revealed.

It is worth pausing here, though, to note that the removal and display of human remains intersects with a long history. On the one hand, white Americans, and their English forebears, had a history of taking and displaying skulls as acts of domination. New Englanders affixed the head of Philip, a Wampanoag leader, on a post outside Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1676. And in 1838, Dr. Frederick Weedon took the personal effects of the Seminole warrior Osceola and then removed his head. At different points in the American South, enslavers displayed Blacks’ heads as warnings against resistance. On the other hand, Europeans and Americans had long kept bones as relics or artifacts of curiosity. Beginning around 1200, the new Gothic architectural style within European churches accorded privileged spaces for the body parts of saints. Holy relics and human remains were essential parts of religious life. Much later, during the Revolutionary era, avowed Loyalist David Redding was caught trying to steal muskets at Bennington, Vermont. He was executed for the crime in 1778. A local resident, Dr. Jonas Fay, collected the body and preserved the skeleton. After being conveyed to another family, the bones ended up back in Bennington at the Historical Museum before eventual reburial. Thomas Paine’s skeleton suffered a similar fate. Disinterred from an American burial plot, the bones ended up in England. They were distributed among different people, some lost or destroyed, others collected and displayed.

Confederates’ quest for bones thus connects to a bizarre history of the use, and misuse, of human remains. Bones from the Bull Run battlefield were taken as acts of domination and displayed as trophies of war. However macabre, human remains became part of the deeply variegated material culture of war. The gravity of civil war and the conditions it generated resulted in “a massive traffic in objects,” as historian Joan Cashin observes, “prompting the redistribution of millions” of objects of war. Bayonets and bullets, fragments from famous trees and notable buildings, articles of clothing and military accoutrements all featured prominently. Human skulls were another matter entirely.

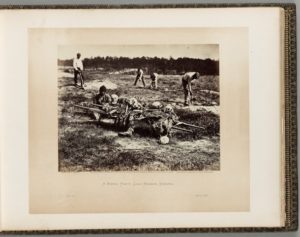

By the time Northern citizens visited the Bull Run battlefield in the spring of 1862, word of the rebels’ atrocities had already circulated. The acts were being used, even exaggerated, for political purposes and publicized in the Northern press. Congress launched an investigation. Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade delivered a summary of the committee’s findings. He framed a key portion of the report around the “treatment of our heroic dead” and punctuated his case by methodically documenting the “fiendish spirit” of the rebels. Wade wisely focused on a theme both familiar and important to nineteenth-century Americans: the care, burial, and memorialization of the dead which formed key elements of the Good Death. Civil War Americans saw the human body, even in death, as central to selfhood and individuality. Bodies were fastidiously prepared and carefully buried. Yet war had called everything into question. Acting with practicality and alacrity, Americans hastily dug and imperfectly marked graves. Corpses were often comingled in long, anonymous trenches. Soldiers North and South watched on with trepidation as they worried about their potential fate. North Carolinian George Battle, writing to his mother in July 1861, described the Bull Run battlefield as a “most horrible sight.” He came to a Yankee soldier “who had only a little dust thrown over him.” Worms were “eating the skin off his face,” and Battle shuddered “to think that perhaps I may be buried that way.”

The antebellum era saw the rise of rural and garden cemeteries. Battlefields not only obliterated the boundaries between the living and the dead but also threatened the sanctity of human remains. Frederick Scholes of Brooklyn, New York, visited the battlefield in April to find his brother’s body. He met a Black man, Simon, “who stated that it was a common thing for the rebel soldiers to exhibit the bones of the Yankees.” Scholes surveyed the area and found the disturbed grave of a Zouave. He then uncovered a long trench containing bone fragments. In one instance, he found a sawn shinbone. “From the appearance of it,” Scholes conjectured, “pieces had been sawed off to make finger-rings.” Another visitor to the area, G. A. Smart of Cambridge, Massachusetts, went in search of his brother. He found the uniform—homemade by their mother—but “no head in the grave, and no bones of any kind.” Scenes from Bull Run shattered any hope that the Civil War’s Union dead would be treated with the dignity that cultural norms demanded.

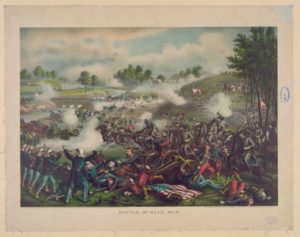

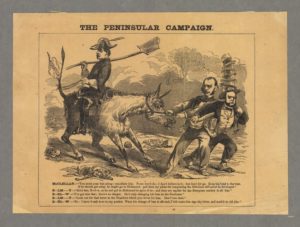

Soldiers, citizens, and the enslaved encountered the aftermath of battle for the first time in the summer of 1861 and spring of 1862. The harrowing photographs of the Antietam battlefield, which forever changed public representations of war, were still months away. Most Americans understood battle in a highly idealized form later captured in the lithograph, “Battle of Bull Run,” by the Chicago-based firm Kurz and Allison. Although wounded men are present, there is a total absence of blood. Those figures portrayed in the act of being shot are gallantly posed. And the neat, tidy lines of soldiers romanticize the chaos of combat. (Figure 1)