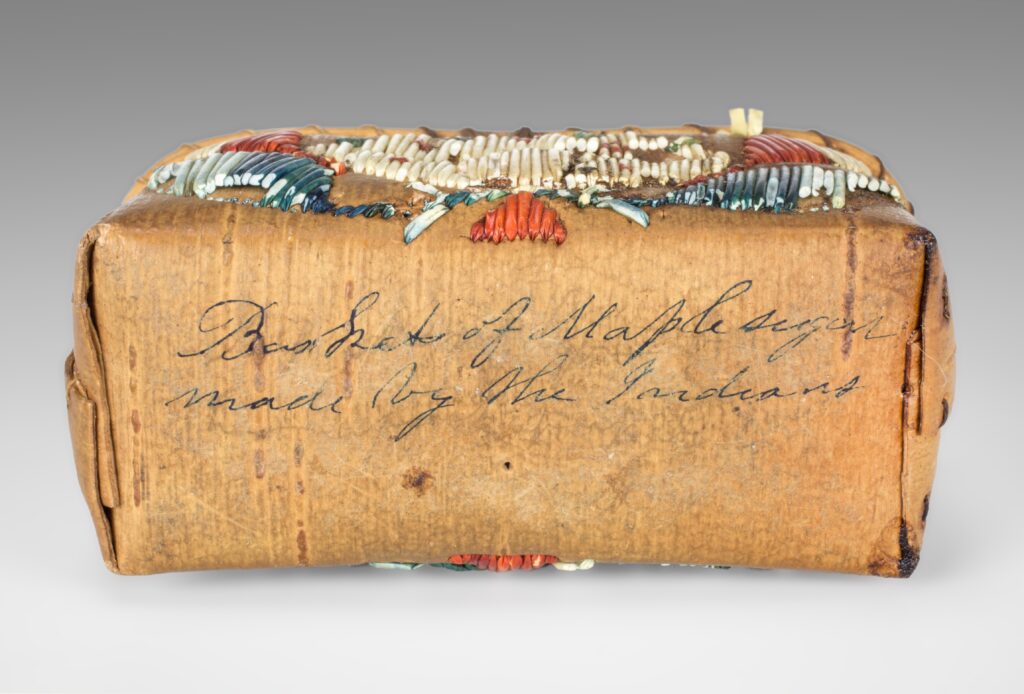

In the 1820s or 1830s, a Native woman from the Great Lakes crafted this miniature mokuk, or maple sugaring basket, and sold it to a non-Native buyer. She folded the birchbark into a box, sewed its edges with twisted spruce roots, affixed a cedar rim, quilled patterns of flowers and leaves on the sides, and filled it with a few tablespoons of maple sugar. She then affixed a lid, which has since gone missing, presumably lost after the buyer removed it to taste the sugar. Today, the mokuk sits in the collections of the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, where it recently reconnected with Eric Hemenway, the Director of Repatriation, Archives, and Records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians as part of a broader project to restore relationships between material culture and descendant communities. This community-engaged methodology is key to recovering the histories of Indigenous material culture.

Tracing Material Culture Histories: A Miniature Mokuk within Networks of Indigenous Resistance

Even before the miniaturization of mokuks as souvenir items, these folded birchbark baskets served as trade items that also facilitated diplomacy between Native and colonial nations.

I first encountered this Indigenous Belonging as an undergraduate at Mount Holyoke College in 2014, when the college was in the process of becoming compliant with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), nearly twenty-five years after the law came into being. In the process of reviewing the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum’s Native American collections, the associate curator of the museum, Aaron Miller, highlighted a significant collection of Native-made items held within the College’s earliest collection, entitled the Missionary Collection. Mount Holyoke was initially founded in 1837 by Mary Lyon as a female seminary, which aimed to train women primarily as teachers or Protestant missionaries. Lyon was a significant supporter of missionary work throughout her lifetime, and maintained connections to family friends and Mount Holyoke graduates who worked as missionaries in multiple locales, including Anishinaabe homelands. These missionaries often sent items back to the seminary, which became the Missionary Collection.

Before the Art Museum was established in 1876, the Missionary Collection was initially displayed in Mount Holyoke’s original seminary building after 1837 as “curiosities,” a term that reveals Eurocentric and colonial ideas about Indigenous material culture. European and American collectors acquired Indigenous material culture to display in cabinets of curiosity, which reflected colonial categorizations of Native people as savage and connected to nature. This process removed these Native-made items from existing networks of community knowledge and instead displayed them as exotic specimens. I challenge these frameworks, instead honoring material culture as present-day receptacles of Indigenous knowledge that educate and transmit information to current people. Rather than terms like “curiosity” or “object,” I refer to these items as Belongings, following the work of Lorén Spears, the Narragansett and Niantic executive director of the Tomaquag Museum, who writes that this term “recognizes that they are interconnected to the cultural contexts of their creation and maintain connections to people, both historical and contemporary.”

The Mount Holyoke College Art Museum knew very little about the miniature mokuk when I began researching it in 2014, but the mokuk is not a “curiosity.” While at the museum conducting research within this collection, I took Christine DeLucia’s material culture seminar, which—alongside her mentorship over the years—has deeply shaped my understanding of these histories of collecting and the “transits of Indigenous material culture” within institutions like Mount Holyoke. In a recent Commonplace essay, DeLucia identified critical interdisciplinary methodologies for researching Indigenous Belongings that are missing provenance information and appear “lost,” providing clear ways to retrace their pathways and reconnect them with descendant communities. This piece takes up these methods via the miniature mokuk to argue for the importance of restoring Indigenous histories and knowledge to collections in order to facilitate relationships between Native people and their cultural Belongings, as well as to ensure these Belongings are seen as vital sources for understanding and reckoning with institutional histories of colonialism.

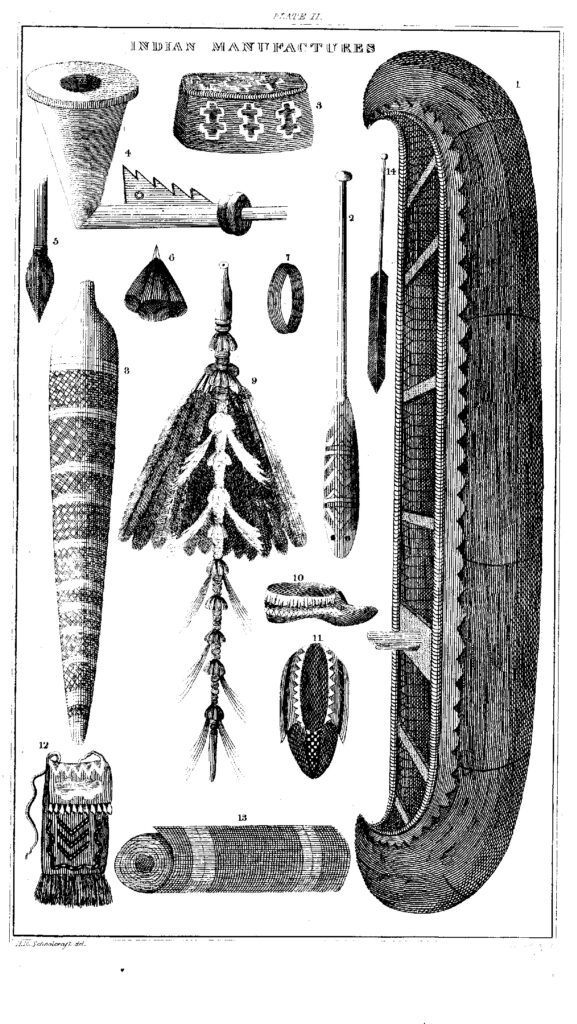

The Missionary Collection includes one other birchbark miniature: a canoe decorated with green, orange, and red flat quillwork. During his 2023 visit, Hemenway stated that he believed both the mokuk and the canoe were from Michilimackinac, noting that early Odawa quillworkers used orange quillwork. While only the canoe is listed in a “Catalogue of Cabinet of articles Sent by Missionaries to Mt. Hol. Fem. Sem. all before 1892,” both miniatures likely entered the collection from the same source, although perhaps not from the same artist or community. Several miniature mokuks collected by Austrian trader and businessman Johann Georg Schwarz, which are currently held in the collections of the Weltmuseum Wien, display remarkable similarities to the mokuk in the Missionary Collection, evincing a potential connection between these Belongings. Schwarz traveled to Michilimackinac in 1820 and 1821, during the same decade that missionaries with connections to Mary Lyon established themselves on the island. The mokuks held at the Weltmuseum Wien have been preliminarily identified as Myaamia or Menominee. While the mokuk at Mount Holyoke is likely of Anishinaabe origin, its maker is unknown. If it were made by a Myaamia or Menominee artist, its origin at Michilimackinac evinces the intertribal trade networks that continued to structure the Odawa island throughout the nineteenth century.

Though it has no paperwork associated with it, the mokuk includes the following description, written in scrawling pen on the bottom of the basket: “Basket of maple sugar made by the Indians.” This description was likely written on the mokuk when it came into the Missionary Collection at Mount Holyoke, probably between 1837 and 1892. In Anishinaabemowin, specifically the Odawa language, the moon that corresponds to around April is the Ziisabaakdake Gizis, or the Sugarbush Moon, when sap begins flowing from maple trees. Native peoples across the Northeast have crafted mokuks for millennia, which they used to store maple sugar, made during the Ziisabaakdake Gizis by reducing maple sap over a fire in trays until it became crystallized and the water evaporated. As Leah Hopkins, a Narragansett museum educator currently working at the Haffenreffer Museum at Brown University, has described, mokuks are an important Indigenous technology that kept bacteria out of maple sugar and that effectively stored it for long periods of time—like a “traditional Tupperware.” The one at Mount Holyoke is a miniaturized version of a mokuk, made to sell to Victorian Americans in the nineteenth century as a means of making money after the imposition of capitalism and policies of land loss that deliberately prevented Indigenous access to homelands that held the ecological means for their survival.

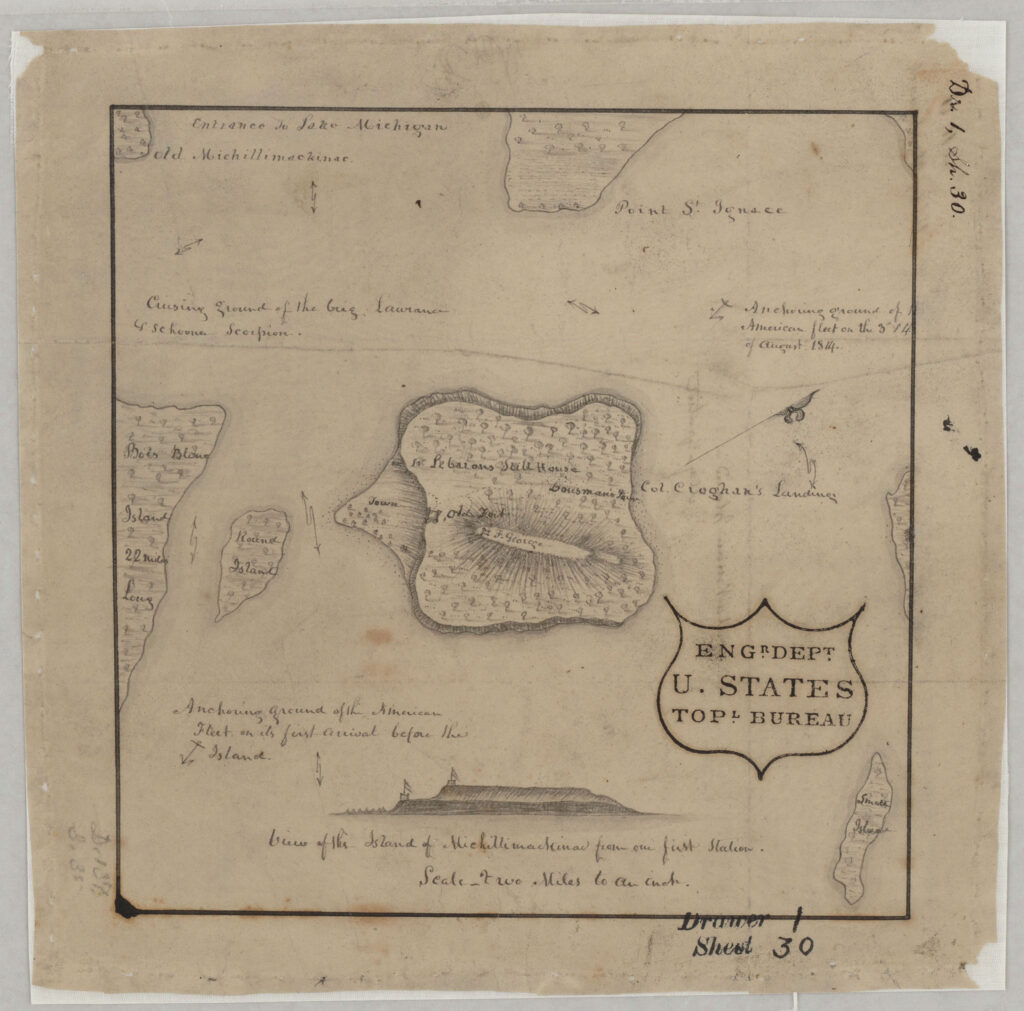

To trace the origins of these two Belongings, I turned to Mount Holyoke’s archives and special collections, which holds a repository of documents related to missionary work at the Seminary. There, I found letters between Mary Lyon and her close friend Amanda White-Ferry, who served as a missionary at Michilimackinac, Michigan, in the early nineteenth century. Amanda White was born in the same year (1797) and place (Ashfield, Massachusetts) as Mary Lyon, and knew her well. In 1823, White married William Montague Ferry, moving with him to Michilimackinac. Their daughter, Amanda Harwood Ferry, later graduated from Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in 1847. At Michilimackinac, William Ferry became the first Superintendent of the Protestant Mission to the Indians established by the United Foreign Mission Society in 1823, which also opened a mission school that November, where Amanda taught. In 1821, two years before the establishment of the Protestant Mission, Henry Schoolcraft had called for the establishment of missionary schools. He wrote, “There is neither school or preaching upon the island . . . there appears therefore in the present society of the ’Mackinac the want of a preacher, a school-master, an attorney, and a physician,—of merchants there are always too many.” The White-Ferry family responded directly to his call, filling the positions of both preacher and schoolmaster on the island. One of the known students at their Presbyterian school was William Blackbird, the son of Odawa leader Mackadepenessy and the brother of author Andrew Blackbird and quillworker Margaret Blackbird Boyd. Each held significant leadership roles in the Odawa community at Waganakising, the home of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians.

Michilimackinac is an Odawa place where two Great Lakes, Michigan and Huron, meet. This island was a traditional gathering place where Native peoples engaged in exchange, diplomacy, and occasional conflict for millennia before European conquest. Despite colonial impositions, including the establishment of a colonial fort that was at various points controlled by French, British, and American forces, Michilimackinac remained a collective and contested Indigenous place. According to Andrew Blackbird, William Blackbird’s brother and the Odawa historian and leader who published a History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians in 1887, in their agreement with the United States’ government when they were forced to cede the island, Ojibwe people reserved “a strip of land all around the island as far as a stone’s throw from its water’s edge as their encampment grounds when they might come to the island to trade or for other business.” This agreement demonstrates how Indigenous mobility practices persisted throughout early American history, as well as the strategic ways Native nations protected their rights to return to places like Michilimackinac on a seasonal basis.

The need to reserve this land responded to destructive settler colonial policies. Mokuks played a critical role in securing Indigenous survival despite land loss. Even before the miniaturization of mokuks as souvenir items, these folded birchbark baskets served as trade items that also facilitated diplomacy between Native and colonial nations. A journal from between 1795 and 1801 kept by Thomas Duggan, the storekeeper of the British Army’s post at Fort Michilimackinac, lists more than two hundred mokuks full of maple sugar brought by Native people from multiple nations, including the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi as well as Cherokee and Sioux. They traded these mokuks in late spring and early summer alongside beaver skins and other items not only to receive provisions, but also to conduct diplomacy with the British and, in the words of Lisa Brooks, to “bind words to deeds” using strings of wampum. This exchange of material culture not only secured food, arms, and other supplies, but represented reciprocity through gift-giving and trade, as affirmed by Duggan’s terminology of “presents” to describe these provisions. Yet this terminology also represented British paternalism. Duggan mistook these reciprocal exchanges as “charity,” describing the Native peoples as “children” and the English as their “father.”

The miniaturization process reflected the growth of tourism in the Great Lakes region in the early 1800s, when wealthy Victorian Americans travelled to and summered at sites within Anishinaabe homelands. As Henry Schoolcraft listed in 1821, rush mats, mokuks, quilled moccasins, shot pouches, and “other fancy goods of Indian fabric” were “generally in demand as articles of curiosity” by visitors to Michilimackinac. Native people adapted their material culture to this growing market, and it was within this context that the White-Ferry family likely acquired the miniature mokuk. Amidst their missionary conviction to civilize and convert the “savages,” a goal clearly articulated in the letters exchanged between Lyon and White-Ferry, a Native artist folded, sewed, and quilled this miniature birchbark basket. The mokuk is a key to understanding material networks of Indigenous resistance to these settler colonial processes across the Great Lakes.

While the miniaturization of mokuks reflected Indigenous adaptation to Victorian American desires, the Native woman who crafted it drew from longstanding networks of environmental knowledge, as described by contemporary artists like Odawa quillworker Yvonne Walker Keshick. During a 2013 conservation consultation session at the National Museum of the American Indian, Keshick shared how her mentors have taught her that “the bark is ready to pick from the trees when the strawberries are ripe in June.” The process of harvesting bark was also spiritual. As Keshick explained, she “puts tobacco down at the first tree, general prayer for all the trees that I’m going to cut. We don’t cut every tree we come to. If the tree is stripping, we cut.” The respect and mutuality that Keshick describes operated in contravention of European policies of private property ownership and environmental exploitation. When they gathered birchbark, spruce roots, cedar, and porcupine quills to make mokuks and other Belongings, Native artists defied civilizing missions and government-sponsored land loss, such as those spearheaded people like Schoolcraft, White-Ferry, and Ferry. Forced to enter the capitalist economy, Native people exploited the existing market of visitors, missionaries, and traders to make a living through their material culture. The goods and money they received in exchange for these items were not adequate payments for their labor or craft, but souvenirs helped Native communities persist. Keshick also described how quilled birchbark baskets have been used by the Anishinaabeg throughout history as boxes to store dried food, seeds, herbs, and medicines. Reflecting on the arrival of Europeans, she remarked, “I don’t think Odawa people could have survived without the use of the birchbark tree.” Her gratitude to birchbark for its role in Indigenous survivance speaks to the importance of mokuks and other Belongings in the study of Indigenous history.

Where, then, does that leave us with regards to the miniature mokuk, which almost certainly traveled to Mount Holyoke from Michilimackinac via the White-Ferry family? While it sits in storage at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, disconnected from its Native creator and the environment of the Great Lakes, this Belonging retains connections to this place and the peoples who continue to live there. Moreover, during Eric Hemenway’s visit, he noted the mokuk’s ongoing relationship not only to Native people and places, but also other Belongings, including the group of miniature mokuks at the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna, Austria. In 2016, Hemenway and other members of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians traveled there to study the museum’s Indigenous collections from the Great Lakes and advise in the conception of a permanent exhibition. At Mount Holyoke, nearly a decade after I first encountered the mokuk and seven years after Hemenway visited the Weltmuseum Wien, we found ourselves wondering if any of the mokuks in Vienna had been crafted by the same artist. What would it mean to return these mokuks to their homelands to visit each other and their descendant communities? What new connections would form?

Further Reading/Watching/Listening

Andrew J. Blackbird, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan; a Grammar of their Language, and Personal and Family History of the Author (Ypsilanti: The Ypsilantian Job Printing House, 1887).

Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

Gerard van Bussel and Eric Hemenway, eds., Around Lake Michigan: American Indians, 1820-1850 (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2021).

Christine DeLucia, “Antiquarian Collecting and the Transits of Indigenous Material Culture,” Commonplace: the journal of early American life, accessed May 17, 2023.

Thomas Duggan Journal, 1949.M-731, William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan.

C. Edwards, “Catalogue of Cabinet of Articles sent by Missionaries to Mt. Hol. Fem. Sem. all before 1892,” Mount Holyoke College Art Museum: A-1, section on “American Indians.”

Leah Hopkins, “Gather. Make. Sustain. Maple Madness,” Haffenreffer Museum, Brown University, March 8, 2021.

Theodore J. Karamanski, Blackbird’s Song: Andrew J. Blackbird and the Odawa People (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2012).

Sylvia S. Kasprycki, “A Devout Collector: Johann Georg Schwarz and Early Nineteenth-Century Menominee Art,” in Three Centuries of Woodlands Indian Art, eds. J. C. H. King and Christian F. Feest (Altenstadt: ZKF Publishers, 2007).

Scott Manning Stevens, “Collectors, and Museums: From Cabinets of Curiosities to Indigenous Cultural Centers,” in The Oxford Handbook of American Indian History, ed. Frederick Hoxie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

James McClurken, Gah-Baeh-Jhagwah-Buk, the Way It Happened: A Visual Culture History of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa (East Lansing: Michigan State University, 1991).

Henry Schoolcraft, Narrative Journal of Travels Through the Northwestern Regions of the United States: Extending from Detroit Through the Great Chain of American Lakes, to the Sources of the Mississippi River (Albany: E. & E. Hosford, 1821).

Lorén Spears and Amanda Thompson, “‘As We Have Always Done’: Decolonizing the Tomaquag Museum’s Collections Management Policy,” Collections 18, no. 1 (March 2022): 31-41.

Mina Toulouse, Theodore Toulouse and Yvonne Walker Keshick, “Conservation Consultation for Beyond the Horizon Anishinaabe Artists of the Great Lakes,” National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, November 25, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRn07eHpvAE.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Eric Hemenway (Director of Repatriation, Archives and Records, Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians), Aaron Miller (Associate Curator of Visual and Material Culture and NAGPRA Coordinator, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum), Christine DeLucia (Associate Professor of History, Williams College), Steven Lubar (Professor of American Studies, History, and History of Art and Architecture, Brown University), and Adriana Greci Green (Curator of Indigenous Art of the Americas, Fralin Art Museum, University of Virginia) for your collaborative work to help trace histories of this miniature mokuk and critically interrogate museum collecting practices.

This article originally appeared in September 2023

Allyson LaForge is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at Brown University whose research engages Native American and Indigenous Studies, settler colonial studies, and histories of the Native Northeast. Her dissertation project, “Materializing Futurity: Networks of Native Organizing in the Northeast,” examines the role Indigenous material culture played during transnational Native Northeast movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, led by coalitions of Native leaders, activists, artists, craftspeople, and writers who worked to resist settler colonialism and ensure Indigenous futurity.