In February 2023, I impulsively booked tickets to Glasgow to visit an old friend. I have been completing a bachelor’s degree in English Literature and American Studies at the University of Manchester, an urban campus in a city shaped by the nineteenth-century cotton trade. But Glasgow is older—and cooler. The buildings are moody and gothic, surveyed by the looming angels of the Necropolis cemetery. When it rains, as it often does, the sandstone shines. In place of huge, flat shopping centers, cobbled Glasgow offers rows of unnamed storefronts selling eclectic antiques.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the Hands of the Red Scared

Again and again, the filmstrip shows its viewers images of women in states of distress.

Rooting around in one of those shops, I found it: a little tin so small that it could fit in your fist. UNCLE TOM’S CABIN was stamped on its label. I bought it without opening it. It cost two pounds.

At the time, I was enrolled in Dr. Gordon Fraser’s class, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a Global Media Event.” Each student in that class was asked to develop a project that considered how readers around the world responded to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous anti-slavery novel. I still wasn’t sure about my research project, although I had a few ideas. I had read a lot of Toni Morrison, and I was thinking about The Bluest Eye and its Shirley Temple doll, a cultural derivative of the angelic little Eva from Stowe’s novel. Perhaps I could find British dolls referencing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, I thought. But serendipitously, I found a mysterious tin labelled with the name of the novel I was studying in class. I felt obligated to investigate.

My friend’s heating was broken, so I sat in bed at four in the afternoon, shivering from the cold. I heated my palms with my breath and tugged at the tin. It was a roll of film. Holding it up to the light revealed its title: “Great Books Retold In Pictures” and “A Beacon Filmstrip.” So, I thought, this is a filmstrip. Whatever that is.

|

|

|

|

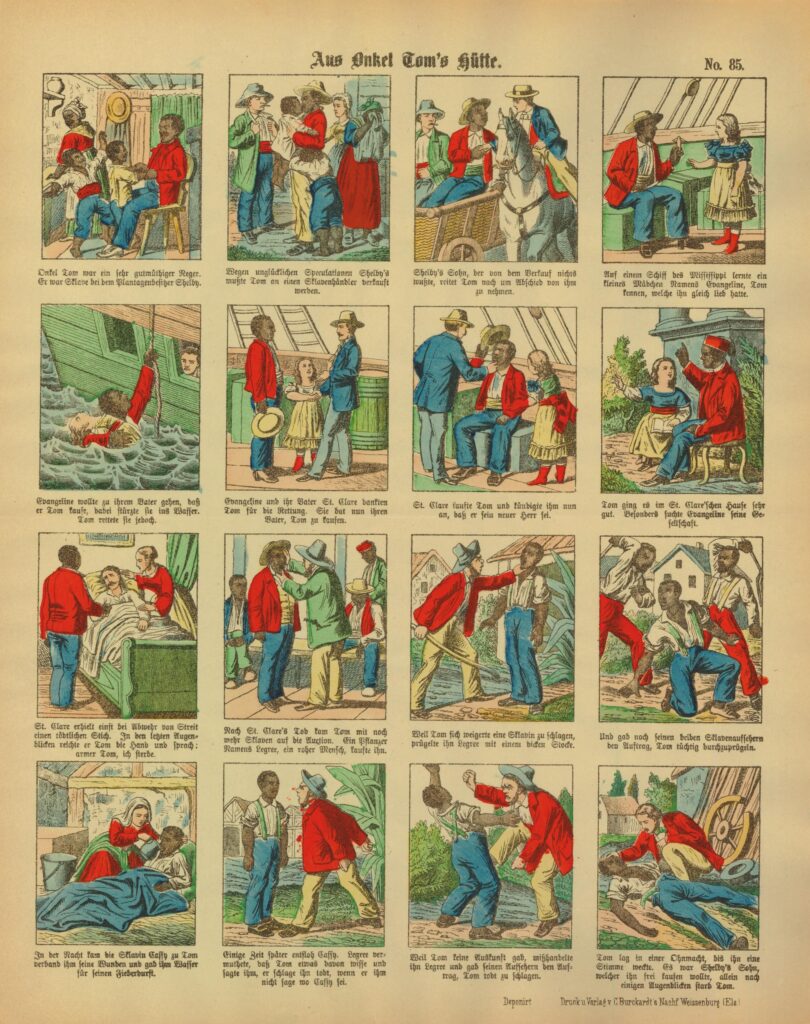

Figures 4a-e: Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe part of Great Books Retold in Pictures. Click images to expand.

When I get something in my head, I can’t shake it, and this was in my head. I scoured antique sites and publisher’s logs. The name “Beacon” turned up nothing related. In fact, I came to realize, the record of filmstrip publishers, or the use of filmstrips at all, is extensively erased. Predating wheely-TVs and PowerPoint presentations, filmstrips are a largely forgotten form of educational technology. They were invented in 1943 and used for geography, history, and science. A teacher armed with a filmstrip could project a series of still images onto a screen, guiding students through a pre-written educational script. The Irish Catholic journal, The Furrow, endorsed the use of filmstrips in a 1960 article, explaining:

“This learning process may be pleasant or unpleasant and . . . [we] would prefer it to be pleasant . . . We should never underestimate the value of pleasant sentiments . . . where knowledge is worse than useless unless it is accompanied by love.” Learning made “pleasant”: the act of showing filmstrips, to the Furrow, was an act of love. Peering at the mauve-tinted illustrations shaded and flattened in budget history textbook style, illuminated bleakly in the weak, cold afternoon light, I was skeptical.

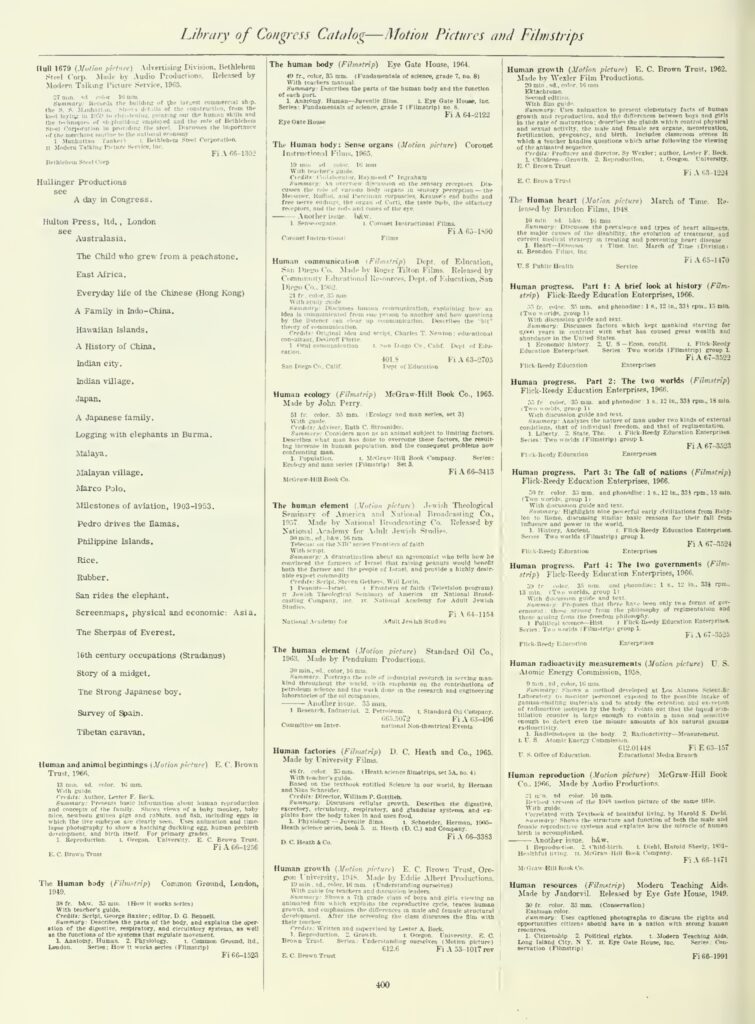

Back in Manchester, and hitting a wall in my research, I turned to my lecturer. Gordon was able to find records of a series of “Beacon Filmstrips” released under “Hulton Press,” which were recorded in a US Library of Congress Catalog for 1968. A hunt for “Hulton Press” led us to the UK government’s registry of corporations and to a company named “Hulton Educational Publications,” incorporated in 1959. We were hoping to find details about the company’s goals in its corporate filings. Why was it incorporated? Why did this British firm make an educational filmstrip based on an American novel?

This is where the story started to get strange.

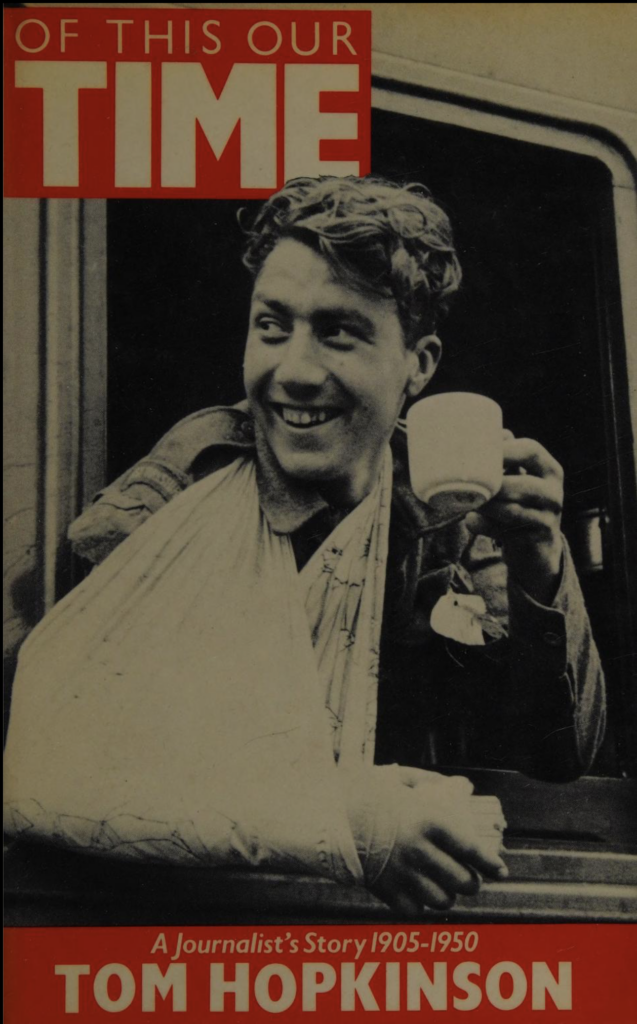

The company’s founder, Edward George Warris Hulton (1906–1988), was the son and heir to the estate of British publishing magnate Sir Edward Hulton, 1st Baronet. Hulton could only be described as a rabid anti-Communist. The journalist Tom Hopkinson explains that he was forced by Hulton to resign from his job as photo editor of photojournalism magazine, The Picture Post. In his autobiography, Of This Our Time (1982), Hopkinson reported that he had produced an expose on the allies’ treatment of prisoners during the Korean War. Hulton, who owned The Picture Post, was furious. Hulton said: “I cannot permit editors of my newspaper to become organs of Communist propaganda. Still less to make the great newspaper which I built up a laughing-stock.” Hopkinson got the last laugh, though. Shortly after his resignation, the magazine had lost so much money that it closed in 1957. This story gave me a picture of the person I was researching—the man who produced this “Beacon Filmstrip” of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Anti-communism was inextricable from anything he might produce.

I looked back at the images in the old filmstrip. Could I detect Hulton’s aggressive anti-Communism in his twentieth-century illustrations of this nineteenth-century novel? There was something strange about the filmstrips’ retelling of the book. What I saw in the still images was a recurrent pattern of female suffering. Certainly, Stowe’s novel is organized around the experiences of women—mothers and young girls, especially.

|

|

|

|

|

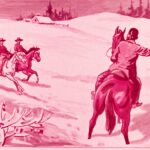

Figures 8a-e: Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe part of Great Books Retold in Pictures. Click images to expand.

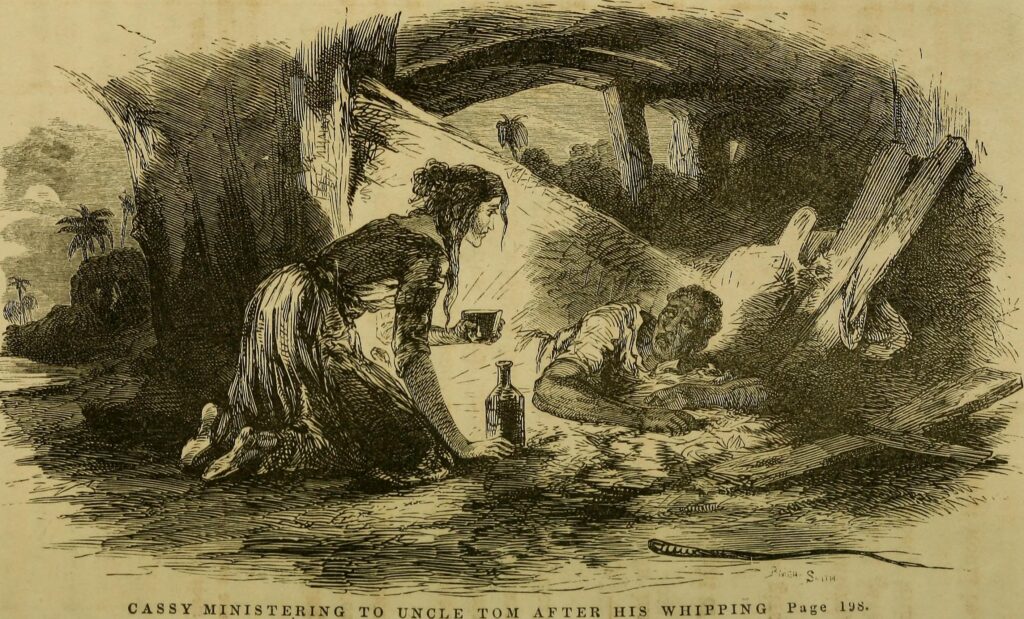

Jane Tompkins identifies Stowe’s focus on the experiences of women and girls as “a monumental effort to reorganize culture from the woman’s point of view.” And yet, in the filmstrip, I saw only some of the women from Stowe’s novel. The clever Cassy, who protects a fellow enslaved woman by pretending to be a ghost, is not visible in the filmstrip. The model Quaker women, whom Tompkins saw as guides to a future, matriarchal society, are also not visible in the filmstrip. Aunt Ophelia, the earnest Vermont woman who abhors slavery—not visible.

In place of these figures, the filmstrip highlights helpless women endangered by a centralized authority. Again and again, the filmstrip shows its viewers images of women in states of distress. In fact, in twelve of the twenty instances of a woman’s appearance in the filmstrip, that woman is in a state of anguish—crying, weeping, begging for mercy. These depictions are antithetical to what Tompkins saw in Stowe’s novel: a reorganization of society around the values of women, a politics borne from maternal morality. Instead, the viewer encounters broken female figures who are dispersed almost at random amongst the scenes: helpless, disempowered.

Strikingly, the images in the filmstrip also resemble those in Hulton’s periodical, The Picture Post. A 1955 article describes the Korean women and children whose lives are torn apart by Communist reformation. A woman “walked for six months to get treatment for her son’s paralyzed arm.” Other women “conceive and bear their children in the dust, and do their business in the nearest ditch.” Hulton pushes the image of these women as human chattel, the currency of war. In a 1949 publication from the magazine set in the immediate aftermath of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, The Picture Post describes the lives of the women and children rendered “Pawns” in “the Fashionable Game called ‘Cold War.’” They are emaciated “ghosts” scouring the countryside for stalks of wheat. Hulton’s magazine is much more interested in describing women alone in suffering than together in survival, and the article makes clear why this is the case. These women are “a fertile breeding ground for Communism.” In short, westerners need to protect these women—or the women will, defenseless in despondency, fall into the arms of Communists.

|

|

|

|

|

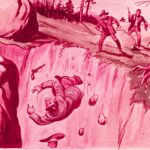

Figures 10a-e: Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe part of Great Books Retold in Pictures. Click images to expand.

Like any adaptation, the Beacon filmstrip calls attention to some parts of its source material and not to others. As I came to realize, Hulton’s filmstrip of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and his Picture Post description of refugee Arab women mask the same thing: women’s political autonomy. Looking back to Stowe’s text, I reflected on how the character of Cassy was Stowe’s subversive answer to those who try to control women’s bodies. Cassy is described as wild and heathenish, and is sexually exploited by her master Legree. And yet Cassy is the moral and political center of Stowe’s parable. This is where I fall head-over-heels for Stowe’s novel. Having lost her own child, Cassy takes a vital maternal role in advising the young, enslaved girl Emmeline. Cassy also stands up to Legree in an act of defense: despite the implications concerning the physical and sexual violence Cassy has been subject to at her master’s hands, she returns to the house to confront him when Legree targets Tom. Women help women and demonstrate profound bravery. This is Stowe’s vision, and it is the very thing that Hulton’s Picture Post and his filmstrip of Uncle Tom’s Cabin eliminates. Cassy does not appear once in the filmstrip.

Of course, many have critiqued Stowe by suggesting that her novel is an example of what queer theorists have called heteronormativity, the unspoken assumption that the world is properly organized into male and female domains and that differences in sexuality are defined as deviancy. I understand why critics have come to this conclusion. And yet viewing Hulton’s revision of Stowe’s novel renewed my belief that Stowe was communicating something important about the role of women in a culture defined by the violent behavior of men. Stowe’s politics can be read through Cassy: a model of maternal strength as a political force. Her sacrifice, like Uncle Tom’s, is martyr-like. Her body, all that she has, is a buffer that protects Emmeline and others from the violence Legree would otherwise have directed at them. The “maternal values” that Tompkins highlighted as the core of Stowe’s philosophy, her political “reworking,” is not heteronormative or even conservative. Instead, Stowe offers an ideal of maternal feelings that fuel political action. This is as brave as it is overlooked, and it is the very thing that Hulton erases from the filmstrip.

In short, when I looked back at the Uncle Tom’s Cabin filmstrip, I realized that Hulton’s anti-Communist project obscured the very thing that I had appreciated about Stowe’s novel: its commitment to maternal values, feminine sentimentality, and Christian virtue—a society remade in the archaic image of Christian motherhood. The literary scholar Jim O’Loughlin has suggested that Stowe’s use of “iconography” and “stereotypical” visual images means that in practice her novel is directly linked to the racist depictions that followed its publication: the minstrel shows and racist caricatures. And yet throughout the Uncle Tom’s Cabin class, I felt inexplicably, passionately defensive of Stowe. Sometimes, I found it almost painful to hear my classmates’ exhortations about Stowe’s “white saviorism,” her supposed ignorance and arrogance. Stowe’s commitment to Christianity was unapologetic. It was this absolutism that, in practice, drove her to challenge racial injustice.

|

|

|

|

|

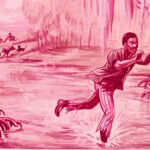

Figures 12a-e: Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe part of Great Books Retold in Pictures. Click images to expand.

Stowe’s use of direct address is brilliant. Through it, she makes clear these revolutionary aims, and she draws the reader in, offers them a seat. Many complain about this stylistic device, one that links women’s narratives as diverse as Charlotte Temple (1791), The Color Purple (1982), and Fleabag (2016). I love it. I love these texts. Stowe, in conversation with her reader, exhorts her to change the world. There’s something lovingly matriarchal about exhortation, as if we are sitting around the kitchen table: well let me tell you, well I’ll tell you this, and so I said to her I said. This is Stowe’s mode of address when she speaks to “the Women of the United States of America” or when she calls out to “You, mothers of America, you who have learned, by the cradles of your own children, to love and feel for all mankind.” This is Stowe’s mode of address when she writes, “By the sacred love you bear your child . . . pity the mother who has all your affections, and not one legal right to protect, guide, or educate, the child of her bosom! . . . And say, mothers of America, is this a thing to be defended, sympathized with, passed over in silence?”

I maintain that you can’t really understand Stowe’s method unless you understand that kitchen table culture: women catching up over (what in England we would call) a cuppa. I feel we ought to understand Stowe’s exhortation as iced tea on the porch after Sunday service, while the husbands do whatever husbands do. “As a mother . . . ,” “Dear mothers”: she wasn’t writing to twenty-first century Liberal Arts students whose most active socialization occurs at Thursday night pre-drinks. She assumes the primordiality of Christianity and maternal values—even treats them as necessary. To what extent should our politics reflect our religion, our morals, our maternity? Absolutely and essentially, she answers.

|

|

|

|

|

Figures 13a-e: Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe part of Great Books Retold in Pictures. Click images to expand.

The Beacon filmstrip I discovered in Glasgow showed none of this. Instead, it depicted women in distress—always in distress, always helpless and crying, always defeated. In the filmstrip, enslaved Black women were pawns in the struggle between white authorities, just as, in The Picture Post, Korean and Arab women were “pawns” of Communism and the “Fashionable” game of “Cold War.” Hulton’s filmstrip company was a footnote in his larger political and economic project. In his 1952 autobiography, When I was a Child, Hulton offers a list of griefs, grievances, and thwarted ambition. He links world politics (“social revolution and total war”) to his own losses. In 1921, he lost his father and much of his father’s newspaper empire. His mother was “shattered” by her husband’s death. His sister died at age twenty-two. The “political advancement” that he had expected remained continually beyond his reach. He ran for Parliament twice as a Conservative, in 1927 and 1931, but lost both times. Hulton is in his autobiography beset from all sides by threats to his wealth, political ambition, and ideology.

Hulton remained ambitious. Hopkinson, the photographer Hulton forced to resign, observed that Hulton in the 1950s “had not yet altogether given up his pre-war parliamentary ambitions.” The filmstrip, then, imperfectly reflects the values of an ardent anti-Communist who had continued to nurture conservative political goals.

These political goals had no real place for female authority. Hulton’s publications regarded women not as co-authors of a political project but as endangered prizes to be won or lost. Examining the images in the Beacon Filmstrip reveals its failure to acknowledge the abiding, enduring power of kitchen table empowerment in Stowe’s novel. Stowe’s politics are organized around women talking, wrestling with the uses of power or the role of morality in the law. Stowe was deeply committed to maternal values, of the right-and-wrong that originates in feminine spaces. Stowe believed that politics ought to reflect the archaic good of maternal instinct.

I am grateful, then, that Stowe’s novel remains an important cultural touchstone, the kind of book that can function as the subject of an entire university class. Vital political progress will emerge from those spaces where women talk. Stowe understood this. Politics begins at the kitchen table, with iced tea on the porch after Sunday Service. Meanwhile, I found Hulton’s filmstrip discarded in an antique shop in Glasgow, stuffed between a plastic rocking horse and a box of forgotten family photographs.

Further Reading

Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time: A Journalist’s Story, 1905-50 (London: Arrow, 1982).

Edward George Warris Hulton, When I Was a Child (London: Cresset Press, 1952; London: Springwood Books, 1978).

Jim O’Loughlin, “Articulating Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” New Literary History 31, no. 3 (Summer, 2000): 573-97.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Janet Fagan Yellin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Jane Tompkins, “Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Politics of Literary History,” in Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790-1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985): 122-46.

This article originally appeared in February 2024.

Georgina Blackburn is a writer from East London currently studying MA English Literature and American Studies at the University of Manchester in Manchester, England. Having written many essays in the past, Georgina specializes in Southern American literature and American Gothic horror aesthetics.