The importance of this object lies not only in its history, but also in the way in which it has been remembered and valued.

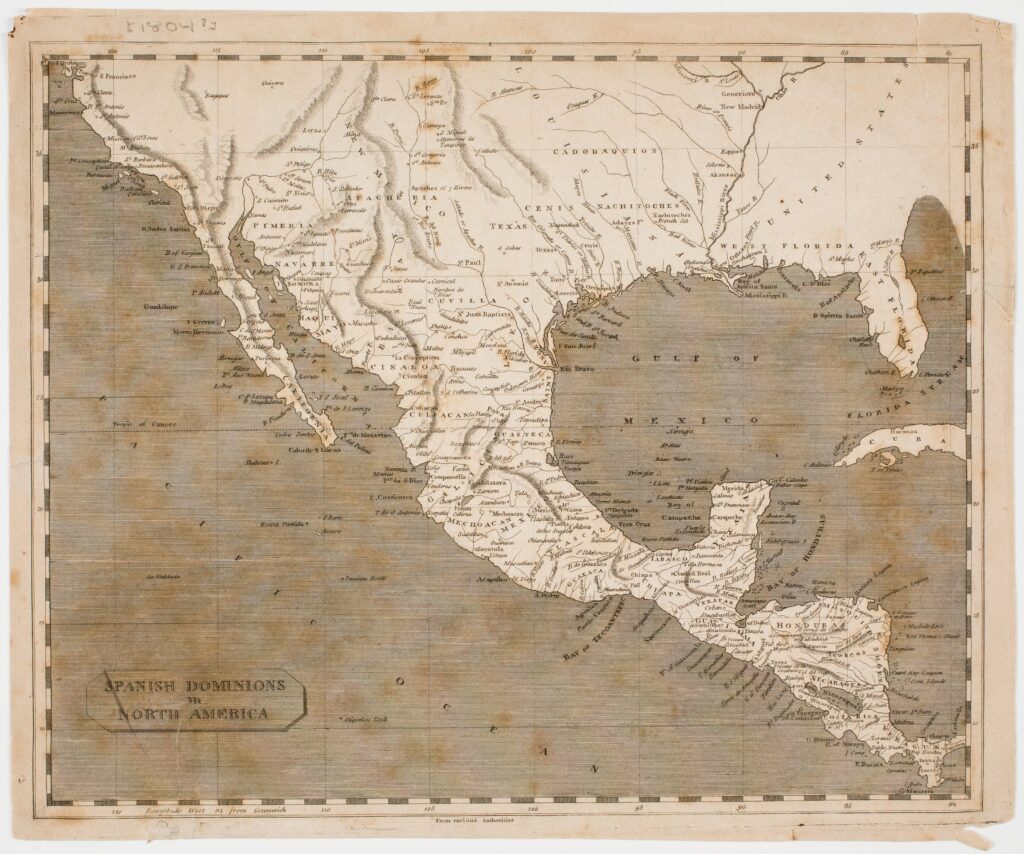

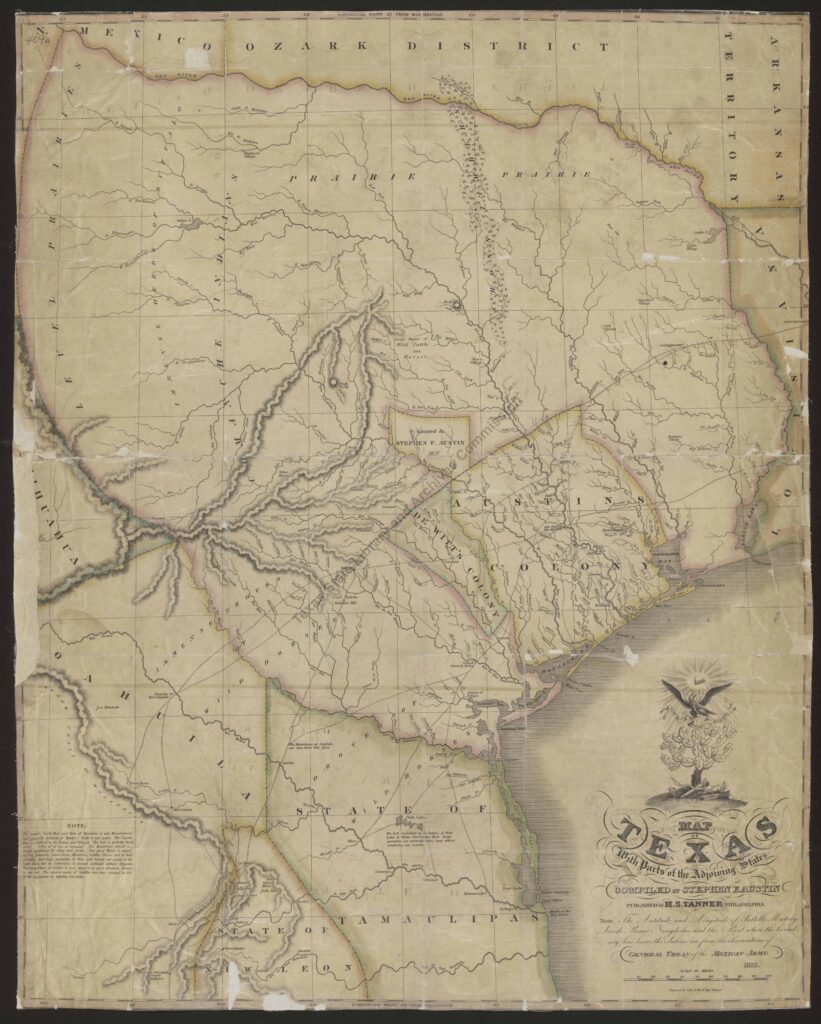

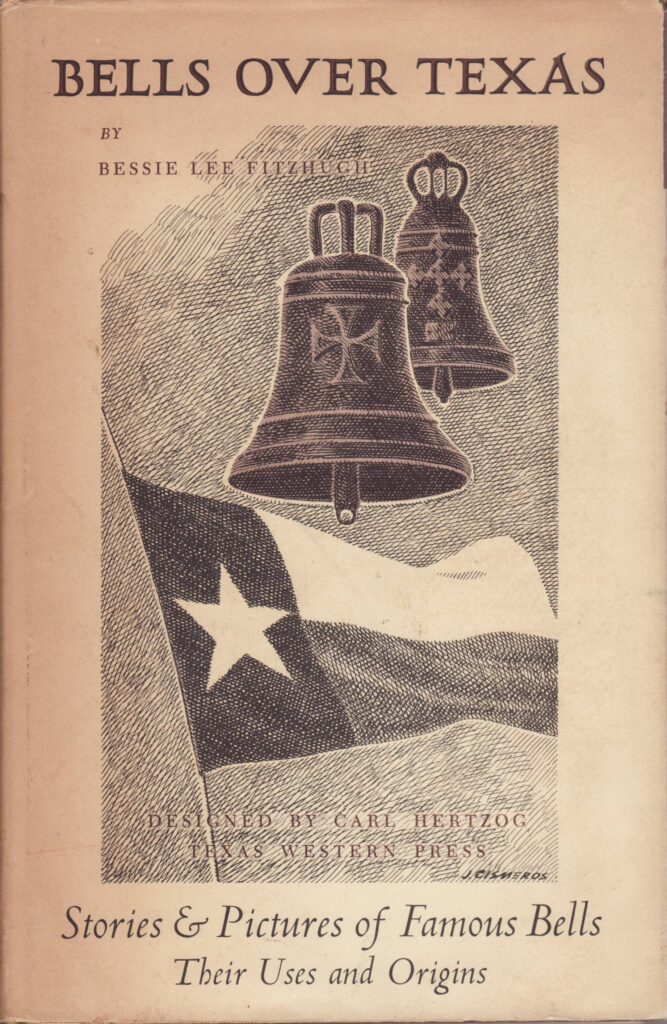

What is it about bells that fascinates us? Few other objects generate such interest among the public and inspire so much poetry, song, and art. Their peals communicate emotion and information, while a glimpse of their form might bring to mind freedom or faith. At the same time, they embody contradiction, representatives of both authority and revolution; the sacred and the secular; joy and sorrow. In Listening to Nineteenth-Century America, historian Mark Smith noted that “bells and their distinctive sounds anchored people to place and time, and emotion was invested in campanological soundmarks.” My ongoing research about the 250-year journey of one bell from a Spanish mission to a museum highlights the symbolic nature of bells and prompts questions about how and why objects are valued by individuals and groups.

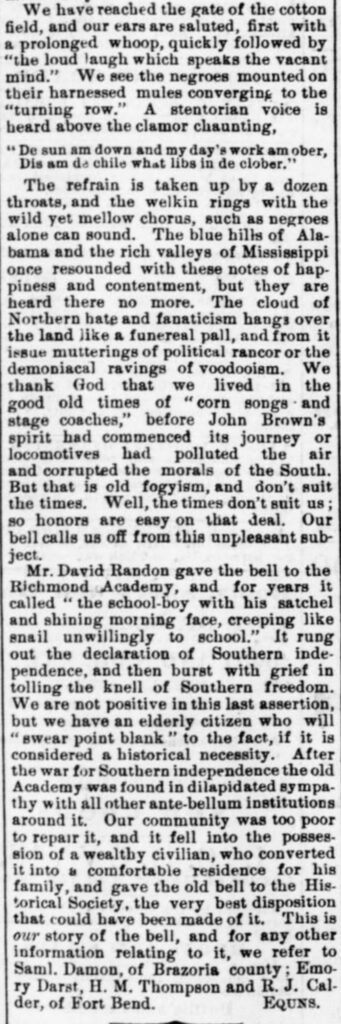

On September 17, 1874, the Galveston Daily News ran a front-page notice about a recent acquisition of the local historical society. Members heralded the transfer of “the celebrated garrison bell of the Alamo” from Fort Bend County Judge William Kendall into their care, although the judge explained that he could not recount the precise history of the item. Over the next month, the newspaper received several replies narrating the bell’s travels. Today it rests in a display case on the second floor of Galveston’s Rosenberg Library Museum.

Standing two feet tall, with a 46-inch circumference at its base, this bell looks much the same as its 1874 description. Time, weather, damage, and use have aged it to a mottled green-gray color. Raised lines encircle the bell at its top. Geometric designs embellish its waist above the rim, and a studded cross adorns one side. Faint traces of letters and dates are scratched on its sides. No clapper hangs inside to strike the bell’s interior and the eyelet from which it once hung is broken. The documentary record provides an inconclusive story of this bell’s journey. Even so, this object, like many others, has much to tell us. Stories about its past reveal much about how an object’s value shifts over time and space, as well as what communities choose to remember and celebrate about their history.