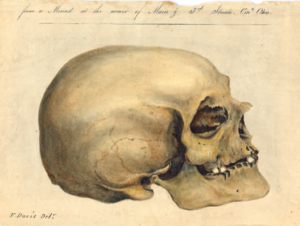

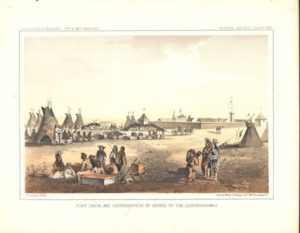

The epidemic had been devastating, Audubon knew. During the weeks spent at Fort Union, he penned an account of the “fearful ravages” of smallpox. He must have known that a people “nearly exterminated” left few to help bury the dead. The skulls Audubon collected for Morton that summer earned casual mentions in his journal. On June 18, he and his companions puzzled over when it might be best to “take away the skulls, some six or seven in number, all Assiniboin Indians.” On June 22, walking over the prairie, “I found an Indian’s skull (an Assiniboin) and put it in my game pouch.” And on July 2, he and a companion “walked off with a bag of instruments to take off the head of a three-years dead Indian chief, called the White Cow.” They tumbled the coffin out of a tree burial and found a body wrapped in two buffalo robes and “enveloped in an American flag.” They took the head, Audubon wrote, and left the rest on the ground.

Morton’s catalogue also credited Audubon with contributing the skull of a 50-year-old Blackfoot man named “Bloody Hand,” along with the heads of two “Upsaroooka” men, both about 40 years old. And two skulls: “1230. Assinaboin Indian of Missouri: woman, aetat. 20. I.C. 85. 1231. Assinaboin woman, aetat. 18. I.C. 85.” “Nos. 1230 and 1231, from J.J. Audubon, Esq., A.D. 1845,” Morton added. Audubon’s memory of the “Indian skull” tucked in his game pouch and Morton’s measurements are all we have left of these two young women—a small trace of racism’s heavy toll.

Scholars once suggested that the mother of the Saint-Domingue born Audubon was of African descent, although evidence suggests rather that his mother was a French-born chambermaid. Audubon constructed an American identity built partly on a foundation of white racism, a fact worth acknowledging. Audubon dressed in the buckskin of an American frontiersman, trafficked in specimens recruited to serve a malicious science of racial hierarchy, and bought and sold a handful of people he enslaved. Although Audubon archives hold only a scant trace of the Assiniboine women, his biographers give us something more on the people he owned, particularly two men, who traveled with him down the Mississippi to New Orleans, where he sold them. The two men disappeared into the cotton economy, while profits from their sale were used to support Audubon’s work on The Birds of America.

I started looking at Audubon’s connections to Morton last fall when a woman from the National Audubon Society wrote to ask about ties between the two men. She told me they were thinking about the racist traces that stain so many of our institutions and about the “whiteness” of birding. Did Audubon’s connection to “scientific racism” matter? And then Morton’s skulls came back into the news with renewed outrage over human remains still in collections at the University of Pennsylvania.

Audubon’s role in our racial reckoning is small. His life was not simple, but he lived with advantages accrued by whiteness. Some of those advantages stuck with him even after he died in 1851. Unlike the women whose skulls he plucked off the prairie or the man he called “White Cow” whose coffin he tumbled to the ground, Audubon remains buried in New York’s Trinity Cemetery and Mausoleum, on a plot that once was part of his estate at “Minniesland” on land that once belonged to the Lenape. His wife and sons buried Audubon in a modest grave, but in the 1880s, members of the New York Academy of Sciences began collecting dimes from school children and dollars from Gilded Age A-listers—Rockefeller, Huntington, Carnegie, Edison, Vanderbilt, Morgan, and dozens of others—to raise a monument over the crypt of the artist ornithologist. You can find it near 155th and Broadway. (Figure 9)