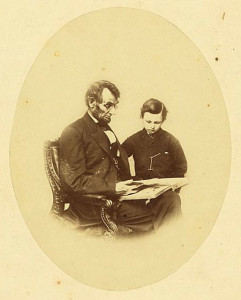

This photograph of Abraham Lincoln and his son Thomas (Tad) was taken by Anthony Berger in Mathew Brady’s Washington, D.C. studios on February 9, 1864. It shows the president and his son looking at a photograph album (a prop that was lying around the studio) together. The photograph was commissioned by the painter Francis Carpenter, who was at the time working in the White House preparing sketches that would serve as the basis for his First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln (1864). This particular sitting led to a number of images that have become part of U.S. national iconography. For example, a portrait of Abraham Lincoln that was taken on this day was used as the basis for the image that appears on the five-dollar bill. This image of the president and his son, however, soon to become one of the most popular and most reproduced depictions of Lincoln, was not published or otherwise publicly distributed until a year after its completion. Only after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 did the image become ubiquitous. The variety of changes introduced to the image in its reproductions offers a fascinating glimpse into how iconography produces narratives and fantasies about national history, culture, and values.