The evolution of the dining room in the nineteenth century

In her popular 1844 domestic manual, The House Book, Eliza Leslie advised her readers about how best to furnish their dining rooms. “A large closet,” she noted, “is indispensable to a dining-room.” By “closet,” Leslie meant a sideboard—the most prominent piece of furniture in the mid-nineteenth-century American dining room. To her middle-class readership, Leslie recommended “two small side-boards, one in each recess,” which would “occupy less space than a large one standing out.” In her discussion of this archetypal fixture of the American dining room, Leslie illustrates some major developments in the nineteenth-century domestic realm: the emergence of the dining room, with its familiar furnishings, as a permanent, dedicated space in the middle-class home and the need for a large, visible storage closet for dishes, tea sets, silver, and all the other accoutrements of middle-class Victorian dining. By looking at the development of a few pieces of dining furniture over the first half of the nineteenth century, we can follow the dining room as it evolved into an essential attribute of the middle-class American home.

The sideboard is perhaps the most illustrative piece of dining room furniture. While it was one of the most fashionable furniture forms, the sideboard was a relatively new entry on the American furniture scene in the early nineteenth century. Sideboards had been used in European courts since the sixteenth century, but the first American pieces were produced in the late eighteenth century by cabinetmakers in cities like New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. An accessory to the dining table, the federal-era sideboard, as pictured below, was a long, narrow table with drawers and small cabinets underneath.

This piece, in the collections of the New York Historical Society, was originally owned by Revolutionary soldier Joseph Wilcox. Measuring about seven feet wide and two-and-a-half feet deep, it has three cabinets and five drawers. The cabinets held plates and serving dishes while the drawers stored silverware and serving utensils. The long, narrow top was used as a buffet during formal dinners. This form of sideboard replaced the shorter, simpler sideboard table form, which had no storage space and served simply to provide an extra surface for meal service.

Eighteenth-century sideboards like the Wilcox one above were owned exclusively by the wealthy. These and other pieces of fine furniture were among the props that refined and genteel families used to display their status and prosperity. With the growth of mechanized manufacturing in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a profusion of affordable consumer goods flooded the American market. To store these goods, the growing American middle class turned increasingly to the hand-crafted furnishings that had formerly adorned only the most stately homes.

Though specialized dining-room furniture grew more widespread in the Federal era, the dining room itself was less specialized, functioning as a sitting room, parlor, or other common room had in most colonial households. Even elite homemakers used their dining rooms for sitting, visiting, and sleeping. For example, one early nineteenth-century visitor found that it was common “for temporary beds to be laid out in dining rooms . . . being of course, removed sufficiently early in the morning to prevent inconvenience.”

In keeping with the multiple uses to which rooms were put in the colonial and early federal periods, dining furniture was designed for flexible use. An example is this three-part dining set, a common form of the period.

This set, consists of three pieces—two circular tables and a central leaf. When not in use, the leaf extension could be stored, and the tables could be pushed against the wall for use as side tables. Also common were sets of three distinct tables, including a center table with drop leaves and two identical side tables. The center table could be extended by lifting the leaves and could stand alone or be combined with one or both of the side tables. When the family was not entertaining, all three tables could be used for card playing, writing, tea, small meals, and other activities.

Toward the beginning of the nineteenth century, as the elite built larger, more lavish homes and designated rooms for specialized uses, dining furniture grew larger and more cumbersome. Sideboards shifted from sleek, long tables to heavily-carved pieces with larger cabinets underneath. And the streamlined legs of the dining tables gave way to heavy, pedestal bases in a style pioneered by New York cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe.

By the third decade of the nineteenth century, householders of middling means began to replicate these trends. The development was made possible, in part, by new mechanized methods for manufacturing furniture. Small furniture workshops gave way to large factories, with dozens of cabinetmakers using mechanically powered lathes and routers to fashion furniture that had long been beyond the reach of any but the wealthiest Americans. Another related development was the evolving eating habits of the American middle class. Improved roads and canals as well the rise of the steamship and the railroad meant that ordinary consumers could now obtain a broader array of foodstuffs.

Meanwhile, new kitchen gadgets and appliances allowed for the preparation of more complex dishes and meals. For example, the cook stove, a requisite component of the middle-class kitchen by the 1830s, provided the cook with several novel cooking techniques that were impossible to achieve over an open fire. While open-hearth cooking lent itself to one-dish meals, the cook stove allowed for different kinds of cooking—boiling, roasting, baking—with the same fire. With one instrument, the American cook could prepare a roasted entrée, boiled vegetables, and a sweet and savory pie. And the entire meal could come out of the oven at once. To help her in this endeavor, she could consult any of a plethora of cookbooks, which the American publishing industry was churning out in the nineteenth century. These books included recipes designed for the new stoves and brought more elaborate and diverse food choices to the middle-class table.

Along with the broadening of the palate came a taste for dining rooms suited to more epicurean appetites. Indeed, by the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the designated dining room had become a central fixture of the Victorian home. Scholars have focused on the parlor as the locus of the growing bourgeois culture of the period, seeing it as central to the domestic ideal of the family by the hearthside but also essential to the middle-class display of its consuming prowess. It was in the parlor that families displayed colorful prints, books, and other consumer goods. But the dining room was equally significant. Like the parlor, this room served as the space where the middle-class family entertained company—and where they showed off the trophies of bourgeois consumerism.

The dining room also had a privileged place in the home as the space where the family gathered at least once daily for dinner. Domestic advisers highlighted the vaunted role of the dining room as a gathering space for the increasingly fragmented middle-class family. For many families, the family meal and particularly dinner became an extremely important ritual, a time for the family to gather, converse, and instruct. It was in the dining room, architect Calvert Vaux explained in 1857,

“that the different members of the family are sure to assemble several times a day, though they may be almost completely separated at other times by circumstances, or the various pursuits that occupy their attention, and it is highly desirable that such a room should fitly and cheerfully express its purpose, and be one of the most agreeable in the house, so as to heighten the value of this constant and familiar reunion as much as possible.”

Parents were encouraged to use the opportunity of this reunion to educate and socialize their children. “More than means of sustaining physical wants,” claimed popular novelist Catharine Sedgwick, family meals were “opportunities of improvement and social happiness,” a chance to “teach, at the rate of three lessons a day, punctuality, order, neatness, temperance, self-denial, kindness, generosity, and hospitality.” If the family was, as historian Mary Ryan claims, the “cradle of the middle class,” then the dining room was the cradle’s cradle.

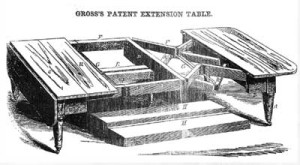

Befitting the dining room’s very particular function, by the 1860s dining furniture was more specialized than ever before. Unlike the multi-use furniture of the early nineteenth century, midcentury and postbellum sideboards and dining tables were permanent features in a room dedicated to their use. The extension dining tables pictured here may have a changeable size, but whatever their configuration, their essential purpose is fixed.

The heavy pedestal bases and patented interior mechanisms made these pieces large and cumbersome. Unlike their predecessors, mid-nineteenth-century dining tables were meant to remain in place.

Likewise, the Victorian sideboards bore little resemblance to the sleek, table-like forms of the early nineteenth century, as this piece from the collections of the Yale Art Gallery shows (link to Yale Art Gallery Website).

This large, heavy cabinet is eight-and-a-half feet wide and six-and-a-half feet tall. Clearly, it was designed to permanently anchor a room. While federal-era sideboards were primarily surface—up to seven feet wide—with small drawers and cabinets underneath, Victorian sideboards like this one had far more storage space. And unlike the low, long federal-era sideboards the newer ones reached to the ceiling, filling the room. Their multiple display and storage spaces were meant to accommodate the family’s growing stocks of silverware, dishes, and other dining utensils. More modest examples of midcentury sideboards, like this one from the 1868 Cabinet Maker’s Album of Furniture, still had impressive dimensions and substantial space for holding and showing off the many props of dining.

The development of the sideboard form from the clean, straight lines of the Federal period to the more elaborate and ornate decoration of the Victorian era reflects, of course, a stylistic shift. But it reflects two other factors as well: the increasing importance of the dining ritual in the middle-class home and the need for more storage.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the number of specialized dishes, forks, spoons, and other dining accessories recommended by domestic advisers grew exponentially. Midcentury dinner sets contained up to five hundred pieces, including dinner plates, soup plates, side plates in various sizes, hot water plates, serving bowls, platters, soup tureens, sauce tureens, and gravy boats. Flatware sets included such specialized implements as fish forks, oyster forks, grapefruit spoons, and asparagus forks. While few middle-class families actually needed or used such a large collection of dishes and utensils, families that hoped to serve proper dinners in several courses required a far greater variety of accoutrements than ever before.

The dining room itself was increasingly designed as a specialized room. Recesses were placed in the walls to accommodate sideboards and in some cases, sideboards were actually built into the dining room walls. Architects arranged dining rooms to have fine views of nature and when nature was not present, as in urban settings, the windows themselves often depicted agreeable stained-glass scenes. Dining-room lighting increasingly took the form of low-slung chandeliers rather than fixtures set on the walls or closer to the ceiling. High enough to cast a pleasing light over the dining table but low enough to inhibit free movement beneath them, these chandeliers secured the dining table as the centerpiece of the dining room.

As the domestic space became ever more idealized in the nineteenth century, the spaces within it took on increasingly important symbolic functions. The dining room served as a family gathering space at a time when the family was celebrated as never before. And it served to display the gentility and prosperity of families at a time when ownership of consumer goods and adherence to a genteel lifestyle were vital status markers. It is fitting, then, that the furnishings that filled the dining room grew more permanent and more imposing as the century progressed. As the home emerged as the theater for middle-class aspirations and accomplishments, the sideboard took center stage.

Further Reading:

Primary sources cited in this article include: Eliza Leslie, The House Book (Philadelphia, 1844); Henry Bradshaw Fearon, Sketches of America (London, 1818); Calvert Vaux, Villas and Cottages: A Series of Designs Prepared for Execution in the United States (1857; reprint, New York, 1968); Catharine Sedgwick, Home (New York, 1837). Information on early nineteenth-century furniture was drawn from: Helen Comstock, American Furniture (West Chester, Penn., 1961); Charles F. Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period (New York, 1966); John T. Kirk, American Furniture (New York, 2000).

On nineteenth-century homes and the growth of the dining room, see: Clifford E. Clark Jr., “The Vision of the Dining Room: Plan Book Dreams and Middle Class Realities,” in Kathryn Grover, ed., Dining in America, 1850-1900 (Amherst, 1987); Myrna Kaye, There’s a Bed in the Piano: The Inside Story of the American Home (Boston, 1998); Charles Lockwood, Bricks and Brownstones: The New York Row House, 1783-1929 (New York, 1972); Richard Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York, 1992); Russell Lynes, The Domesticated Americans (New York, 1963); Susan Williams, Savory Suppers and Fashionable Feasts: Dining in Victorian America (New York, 1985); Kenneth Ames, Death in the Dining Room and Other Tales of Victorian Culture (Philadelphia, 1992); Ruth Cowan Schwartz, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York, 1983).

On domesticity and the middle-class ideal, see: Mary Ryan, The Cradle of the Middle Class (Cambridge and New York, 1981); Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women (New Haven, 1982); Katherine Grier, Culture and Comfort (Amherst, Mass., 1988); Clifford E. Clark, Jr., “Domestic Architecture as an Index to Social History: The Romantic Revival and the Cult of Domesticity in America, 1840-1870,” in Robert Blair St. George, ed., Material Life in America, 1600-1860 (Boston, 1988); Stuart Blumin, The Emergence of the Middle Class (Cambridge and New York, 1989).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.1 (October, 2006).

Cindy R. Lobel is an assistant professor of history at Lehman College, CUNY. She is currently working on a study of food, eating, and the rise of a consumer culture in New York City in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.