Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

The street is a stage; watch the actors strut! The lifeblood of the town flows through its streets. What you learn in the street you unlearn in the parlor. The street has its own loud language. Lost in the street, found in the street. Streets are for seeing. Sin stands boldly in the street, but so does sanctity.

Buildings rise and fall. The oldest structures vanish, the oldest bounds, signs, walls, markets, wells pass away with a speed that sometimes makes the lives of the residents seem long. But the streets, the oldest footprint of the town, remain in so many American cities with surprising obduracy. What story do they tell?

Street: a paved thoroughfare within a town or city lined or intended to be lined with two ranks of houses and of a regular, comparatively broad width, and often possessing a coping or paved footpath. Like the road, the street was a free and public way. To it was fixed a right of common enjoyment and a duty of public maintenance. Yet the street was not a road. A road was a line of travel extending from one town or place to another, a strip of land appropriated for transportation and communication between towns or important sites. A road possessed a right-of-way secured by contract or convention, permitting anyone to cross over lands in private or public hands. Nor was the street an alley, a pathway created to accommodate a private dwelling or structure. Usually an alley was an access path wide enough to permit passage of a large barrow or cart from a lot in the interior of a block to a street. When projectors planned the towns that would serve as the metropolises of the American colonies, there was invariably one road, leading from the coastal town to the interior; there was an array of streets. There were never alleys.

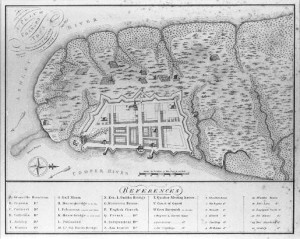

Charleston, like the other colonial centers–Portsmouth, Boston, Newport, New York City, Philadelphia, Newcastle, St. Mary’s City, Annapolis, Jamestown, Savannah, Bridgetown–asserted an ambition to consolidate civic order on relatively unsettled regions. After a decade of troubled habitation on the south side of the Ashley River, the Carolina proprietors in 1680 relocated the center of population of their colony to the peninsula between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. To direct development, they supplied a Grand Model of urban settlement for Charles Town. It projected a town comprised of 337 numbered lots arranged about a rough grid of unnamed streets.

Colonial projectors throughout English America shared a conviction that erecting a port town was the sine qua non of internal improvement. The success of the Spanish in the erection of their American empire was understood to lay in their founding of a network of towns connected to trading ports on the Atlantic and Pacific. But just as those trading towns stood vulnerable to the depredations of sea-faring adventurers (the Sir Francis Drakes and Antony Sherlys of the world), so the American port cities required protection. As the southernmost city of English America in 1680, Charles Towne stood closest to the Spanish in La Florida who reckoned Carolina to be their province of Guale. Built in 1680 on the Cooper River side of the peninsula, it was a walled city.

Oddly, the fort and the street plan didn’t work together. Unlike the fortified cities of northern Ireland, Charles Towne’s streets fail to connect the bastions and redoubts rimming the town. Only the thoroughfare fronting the Cooper River–”The Bay”–and the street connecting the back entrance of town with the front–”Broad Street”–linked important features of the fortification. The fort seems to have been conceived independently, on site, and a four-street by three-street chunk of the Grand Model’s plan superimposed upon it. This arrangement suggests its temporary nature. Looking at the strong outlines in the early city plats and plans, we too readily imagine Charleston girded with a stone (or at least tabby) citadel. But the South Carolina laws tell a different story. The 1704 Statute #234, “An ACT to prevent the breaking down and defacing the Fortifications in Charleston,” clearly visualizes the fort as an entrenchment, an earthen bulwark and a ditch on the inland sides of the city. Subsequent Acts (#235 and 278) outlawed the free range of cattle in the city because they “damnif[ied]” the fortification. Only along the Cooper Riverside (and perhaps the bastions) was the perimeter constructed of more durable material–a brick wall six bricks thick at the base and three at the top. Give the planned obsolescence of Charleston’s fortification, one can readily understand why colony officials began dismantling it after the defeat of the Yamasees in 1717. Governor Nicholson’s expansion plans in the early 1720s led to the leveling of the works and the filling of the ditches. In official documents thereafter, the city’s fortification came to mean the coastal defensive wall.

Charleston was not a chartered city until after the American Revolution. It had no city government, so its improvement depended upon the colony executive and legislature. When strong leaders with a penchant for civic design (Governor Nicholson had already renovated the streetscapes of Annapolis and Williamsburg) took charge, things happened. When the legislature was occupied with other matters, the inattention permitted a kind of anarchy. Nowhere is the fluidity more apparent than in the naming of streets. In the absence of official names, whim and a variety of local practices ruled. Alteration of street names was not unusual, in part because there were no official designations until the 1720s. Street names don’t appear on the earliest plans and maps: on the Grand Model; the 1704 Crisp Map; John Herbert’s 1721 plat of the city; or Governor Francis Nicholson’s redrawn Grand Model, the 1724 “A Platt of Charles Town. Maps noted significant sites and buildings in the town instead of street names. (Crisp even includes the location of Carolina’s first rice patch, south of the inland city wall.) They captured an older sort of mental topography in which a citizen did not orient herself by the street grid, but by proximity to a generally recognized place: a tall church, a popular tavern with a conspicuous sign, a well, a hall. One can easily operate with this sort of mental topography so long as the scale of city is sufficiently intimate that a citizen knows all the principal sites.

A law invoking a site rather than street mentality: An Act for appointing a publick Vendue Master (#298): “Be it further Enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That at least four Days before any Sale is to be made by him the said Vendue Master at publick Out-Cry–he shall fix and put up at the most noted and the usual Places in Charles-town several Notes and Papers, thereby to certify that on such a Day such Goods and Merchandizes or others . . . are to be sold . . . and immediately before such Sale begins, the said Vendue Master shall cause publick Notice to be given by Ringing of a Hand Bell through the most usual and frequented Streets in Charles-Town.”

When street names finally gained enough currency in Charleston that they could be used in legislation, they often derived from some landmark. This did not result in clarity. The moving of St. Philip’s Episcopal congregation, for instance, led to there being two Church Streets during the period from 1724-60: Old Church Street (now Meeting) and New Church Street (now Church). Sometimes, when a street had no single landmark, it had separate names for each block, with some blocks having more than one name. During the 1720s and ’30s, Elliott Street was called Callibeauf’s Lane from The Bay to Bedon’s Alley, or Middle Street from The Bay to Church Street; or, if you were a drinking man, Poinsette’s Alley, after Poinsette’s Tavern. By the 1730s, the indeterminacy of the streets had become such a problem that the colonial legislature began to impose order, declaring in 1734, “That the said Street formerly known by the Name of Dock-street, shall for ever hereafter be call’d and known by the Name of Queen-street.” This action signaled a new will on the part of the government to impose order on the cityscape.

Why was the legislature moved to speak to the streets? Because neglect permitted residents to extend lots into the street and riddle the streetscape with private alleys. “The Uncertainty and Irregularity thereof, by Means whereof great Mischiefs, Law-Suits and Contentions are likely to arise, to the great Detriment of the said Inhabitants; and the said Street so being irregular, the ancient Plan, Model or Form of the said Town is hereby rendered not uniform, or agreeable to the Meetings, Butings and Boundings laid down in and by the said Model or Plan.” Reform and extension of the streetscape would for the next fifty years mean the regularization of a laissez-faire landscape. Commissioners were impanelled to oversee the improvements. Improvements, however, would not mean paving the streets.

The lack of paving on Charleston’s streets during the eighteenth century was one of the more remarkable characteristics of the cityscape. Timothy Ford, when moving from Philadelphia to Charleston late in the century, found the quiet of the city uncanny. The usual sound of urban America–the rattle of carriage wheels on paving stones and cobbles–was missing. Pelatiah Webster in 1765 wrote, “The streets of this city run N. and S. and E. and W., intersecting each other at right angles; they are not paved except the footways within the post, abt 6 feet wide, which are paved with brick in the principle streets.” Captain Martin, caricaturing Charleston in a contemporary verse, noted,

Houses built on barren land No lamps or lights, but streets of sand Pleasant walks if you can find ’em Scandalous tongues, if any mind ’em.

Why didn’t Charleston pave its streets until 1800? Because sand could be cleaned easily and it drained water quickly. Charleston is cursed with water. Paving slows its evacuation. The downside to unpaved streets? When sand was saturated, vehicles with narrow wheels would mire. Carters forced Charleston’s newly impaneled municipal government in the wake of Revolution to pave the streets that served commerce.

Sand streets drained easily and cleaned up easily. Commissioners using labor from the jails (often drunken sailors rounded up from one of two notorious alehouses in the city) scoured the streets periodically. In addition to regular flooding from rains and freak tides, the city experienced numbers of disasters requiring the clearing of the public ways: hurricanes in 1700, 1713, 1728, 1752, and 1804; major fires in 1740, 1776, and 1796. The damage done at these times could be extraordinary.

The South Carolina Gazette, September 13, 1752, “The hurricane of 1752”:

All the wharfs and bridges were ruined, and every house, store, &c. upon them, beaten down, and carried away (with all the goods, &c. therein), as were also many houses in the town; and abundance of roofs, chimneys, &c almost all the tiled or slated houses, were uncovered; and great quantities of merchandize, &c in the stores on the Bay-street, damaged, by their doors being burst open: The town was likewise overflowed, the tide or sea having rose upwards of Ten feet above the high-water mark at spring tides, and nothing was now to be seen but ruins of houses, canows, wreck of pittaguas and boats, masts, yards, incredible quantities of all sorts of timber, barrels, staves, shingles, household and other goods, floating and drive, with great violence, thro the streets, and round about the town.

The Greatest Street in the City: Bay Street, which ran above the Cooper River wall, was the commercial heart of the city. Shortly before the 1752 hurricane, Governor Glen made an estimate of the wealth of Carolina for White Hall. In it he detailed only one street in the colony, The Bay. He supplied a full register of its properties including occupations of the tenants and rental values of every building. There were one hundred lots. Forty-nine were designated “merchants,” six were taverns, two lodgings, one dram shop. There were seventeen vacant lots. Three properties were occupied by widows, one of whom was designated a “lady.” A barber, a milliner, a dancing school, a druggist, two goldsmiths, a physician, three attorneys, the customs collectors’ clerk, two ship carpenters, a blacksmith, and a bricklayer made up the rest of the street. There were two warehouses. Four properties were simply designed by the owners’ names. The annual rental revenue was estimated to be £32,624, with the eastern half of the street (the portion that now makes up Rainbow Row) valued substantially higher on average than the western half of the street. Merchants accounted for £21,450 of the rent on The Bay. Governor Glen did not include any calculation of the value of the wharves and dock projecting waterward from The Bay. These were crowded with one-story crane houses maintained by the merchants, also privies, used by everyone. In the dead center of The Bay was Half Moon Battery, surmounted by the custom’s office, the most public place in town, where visiting ships presented documentation, where pirates were hung, where official proclamations from London and from the Carolina legislature were posted.

The Bay was the most masculine street in town–the haunt of sailors, merchant wholesalers, and the tavern set. As early as 1734, young ladies invaded this masculine zone choosing it as their chief promenade in the city. They abandoned the orange grove and the greens at the town’s western edge. By this, women asserted their right of common enjoyment, that liberty of access and exercise extended to all free citizens on a public street. When the male censors of the Meddlers’ Club rebuked Charleston’s women for the fondness for The Bay, they did not dispute women’s right to be there. Rather, they questioned the honorableness and tastefulness of such recreation:

It is a Custom that will never resound to the Honour of Carolina, and tends to promote Vice and Irreligion in many Degrees. And tho’ it may be objected that the Heat of the Climate will not permit them to walk in the Day, and it can’t but conduce to their Health to walk and take the air; yet I think there are many more fitting places to walk on than the Bay; For have we not many fine Greens near the Town much better accommodated for Air, than a Place which continually has all the nauseous Smells of Tarr, Pitch, Brimstone, &c. and what not, and where every Jack Tarr has the Liberty to view & remark the most celebrated Beauties of Charles-Town, and where besides (if any Air is) there’s such a continual Dust, that I should think it were enough to deter any Lady from appearing, least her Organs of perspiration should be stopt, and she be suffocated.

What particularly irked the Meddlers was the visual access that common seamen had to the most refined beauties in town. Streets were for seeing. Yet ladies, when they went into the streets, had methods for dealing with the public gaze. In 1754 a young man addressed the city tea tables in an open letter to the South Carolina Gazette, expressing his wish “to see the Ladies of Charles-Town walking the Streets, without concealing the Charms of a fine Countenance under a sable Mask. However, should Fashion, a Fear of being thought singular, or any other Motive induce a Lady to appear with a Mask, let it rather serve to adorn her Hand than to conceal the Beauties of her Face.”

The Theater of Manners: Visual promiscuity threatened the privileges of class and the practice of deference. For this reason manners and laws had to be asserted there with particular force. The Meddlers’ letter suggests the difficulty of policing manners. The laws were policed by the watch.

A constable could spot a malefactor more easily in 1730 than he could today, for pale fences rather than brick walls bounded yards. Even the churchyards were not walled until the 1750s. Trees proved less of a visual barrier then than now, for they tended to be cleared from urban lots until the 1770s. The density of building in the old city, too, precluded herbage. For most of the century there was little in the way of visual shelter except the buildings themselves. Once one was outside, one became subject to public attention. This conspicuousness suited a culture that depended upon a bound labor force. The runaway servant and the rebellious slave were two creatures much on the mind of the propertied classes. Attempts were made throughout the century to devise a visual system for marking slaves from freed African Americans. Clothing–pants and dresses made of homespun “negro cloth”–was one way of identifying the laboring portion of the slave population; so were liveries.

One place in the city bore particular scrutiny, the large alehouse on the corner of Meeting and Beresford Alley (now Chalmers Street). The South Carolina Historical Society now occupies what once was the favorite haunt of apprentices, low-life laborers, and sailors who visited the brothels located in the alley. Curiously, the public center of the beau monde was just around the corner on Church Street, where the Court Room of the city’s greatest tavern, the brick theater, and Pike’s Dancing Academy were located.

The streets of Charleston juxtaposed high life with low, fashion with squalor. In 1730-70, the streetscape of Charleston, except for The Bay, did not segregate public places from private dwellings, commercial life from home life, wealthy from poor, freeman from slave. All were mixed together. In this visual welter one asserted one’s place by visual signs–the degree of ornamentation on one’s house, the sword one wore on one’s belt, the fineness of one’s silk mantle. Their proximity to the plain façade, the artisan’s tool-laden belt, the shop girl’s homespun shawl defined one’s place. To the extent that spatial segregation of persons by social hierarchy and function occurred in mid-eighteenth-century Charleston, it happened in the interior of buildings and in yards.

In the street Charleston was a spectacle of variety. Differences of function and style were not arrayed so much by space as by a mental code which allowed one to locate oneself in a social hierarchy. While the order of the city was policed by the agents of the propertied classes, it was preserved as much by manners and indoctrination. Strangers to the city, whether new residents or slaves brought in by force, were compelled to learn the rules of place. By place, they did not then mean one’s geographical location on the streets of Charleston.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

David S. Shields is McClintock Professor of Southern Letters at the University of South Carolina and the author of Civil Tongues & Polite Letters in British America (Chapel Hill, 1997).