How Thomas Paine saw South Asia in North America

Every once in a while, usually after teaching a course on the American Revolution, I wonder if I have the American Revolution all wrong. It’s a sobering thought. After all, I can speak at length about the economic, religious, and political terrain of British America; about the pace and sequence of the imperial crisis of 1763-1775; and about the costs and contingencies of the war that followed. And I can offer up a range of competing historiographies for my class to wrestle with. So, sheer ignorance is not the problem, as far as I know. But I can’t shake the sense that my point of departure for teaching the Revolution is just plain … wrong. More to the point, I wonder if I’ve taken Carl Becker’s famous line about the Revolution being an argument, not over home rule, but over who shall rule at home, too much to heart. I wonder if I’ve been so eager to showcase the Revolution’s consequences for American society that I’ve forgotten an older view of what it originally and fundamentally was: a colonial revolt, not a social revolution.

The writer who has suffered the most from my neo-Becker approach is Thomas Paine. In my class, his incendiary pamphlet of January 1776, Common Sense, always makes an appearance but never a splash. This baffles me. How could students who do so well arguing the fine points of urban rioting and land shortage in colonial America approach this fiery classic with all the enthusiasm of a Clinton at an Obama rally? Why doesn’t it raise even a bit of the passion it did in 1776? Perhaps the problem is that I am too keen to relate Paine to the social and cultural developments we now associate with the Revolution and its aftermath, to enlist him in our ongoing feuds over republicanism and liberalism and democratization. Later in his up-and-down, stranger-than-fiction career, it is true, Paine would draw up plans for a free and decent society, one that balanced rights and duties while renouncing privilege and violence. But that is not what Common Sense is about, and when you try to explain it in those terms, you pour water on its marvelous anger, leaving your class confused and bored. At least, this has been my experience.

Fortunately, I’ve had occasion to revisit Paine’s writings, and what I’ve found makes the pre-Becker view look a lot more interesting. For it seems that Paine was deeply influenced by imperial misdeeds, not only in North America, where he arrived late in 1774, but also in South Asia. At a crucial moment in his life and career, just before his trip to America, he came upon a set of atrocities committed by British soldiers and fortune seekers in Bengal and Bihar—what is now eastern India and Bangladesh. These crimes against people on the eastern fringes of British rule seared dreadful images into his mind, images that he then relayed to people on its western margins. Mass shootings, plunder, famine—this is what Thomas Paine came to know of South Asia’s recent past and to expect of North America’s near future.

Recovering this dimension of Common Sense not only helps us to understand Paine but also to see the American Revolution as a fist shaken at imperial brutality. Although the term empire carried a neutral accent in the moral language of the day, the violence and plunder associated with British advances in the “East-Indies” conditioned Paine’s response to British measures in the American colonies during 1775. The crimes committed against India, he swore that year, would be “revenged.” Yet the great majority of Americans, then and now, had little concept of their connection to the Hindus and Muslims of eighteenth-century South Asia, people compelled by low literacy rates to suffer in silence. This reminds us of a troubling pattern in the life and memory of nations, whereby certain atrocities are reported to the point of exaggeration (see Massacre, Boston) while others all but disappear from the historical universe, reemerging only in coded phrases and vague allusions.

At the beginning of 1772, Thomas Paine was a tobacconist and excise officer whose ideas landed him on the left margins of English political culture. As a friend recalled, he was a Whig of “bold, acute, and independent” opinions. Paine was also a member of the Headstrong Club, a debating society in the town of Lewes, fifty miles south of London. Evidently, his exposure to Enlightenment rationalism (from public lectures and newspapers) and Quaker egalitarianism (from meetings he attended with his father) had convinced him that Britain was too stratified and tradition bound. Indeed, the thirty-five-year-old agreed that year to represent his fellow excise officers in a petition to Parliament, asking for more respect or, at least, better pay.

That he did so speaks to an emerging culture of political dissent and libertarian nationalism. Beneath and between its profoundly conservative and aristocratic institutions, Paine’s Britain was a rude, irreverent place where power was fragmented and liberty celebrated. Britons also built a new camaraderie by identifying with the hearty, apple-cheeked John Bull (the rough equivalent of Uncle Sam), singing “God Save the King,” and claiming to despise all things French. Military heroes were the shock troops of these sentiments, with General Wolfe, martyred on the Plains of Abraham outside of Quebec in 1760, serving as patron saint of Britannia. As of 1772, Paine lived within this patriotic paradigm, addressing his superiors in the deferential idiom of a loyal subject and even writing an ode to the fallen Wolfe three years later.

Along with its celebration of liberty, the moral appeal of early British nationalism rested on a shaky claim to national innocence. Unlike the rapacious Spaniards and benighted French, the story ran, the British led an empire of law and civility. They had no desire to conquer unwilling peoples, only to spread the blessings of commerce and Christianity (in that order). The global truth behind this tale was that no major European power was yet capable of crushing its rivals. In southern and eastern Asia, British merchants and soldiers competed with their French and Dutch counterparts, while the three Islamic empires—the Mughals of India, the Ottomans in the Levant, and the Safavids in Persia—remained strong enough to set the terms of trade and control access to resources. When this began to change on the Indian subcontinent, leaving Europeans in charge of huge tracts of land, the British self-image struggled to keep pace with the rapid expansion of the British Empire.

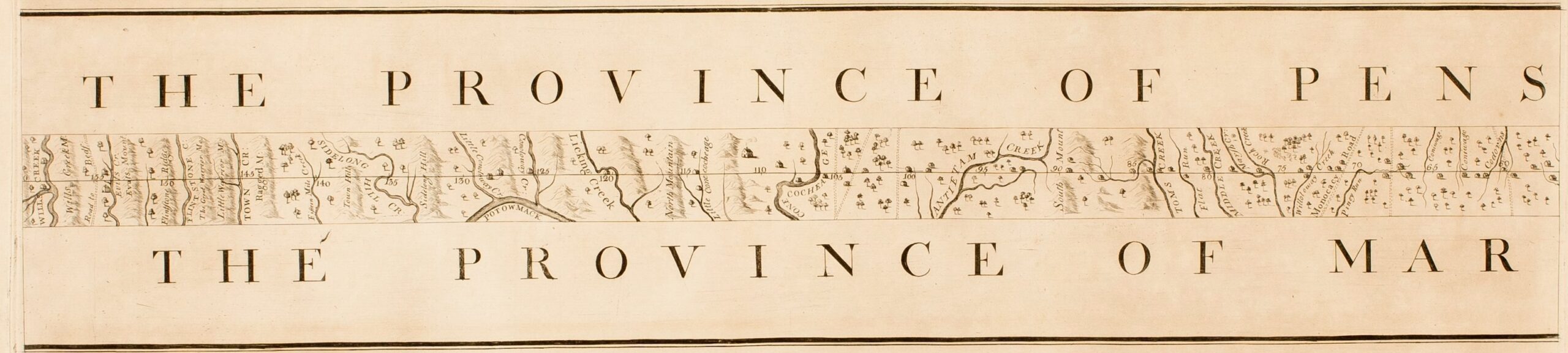

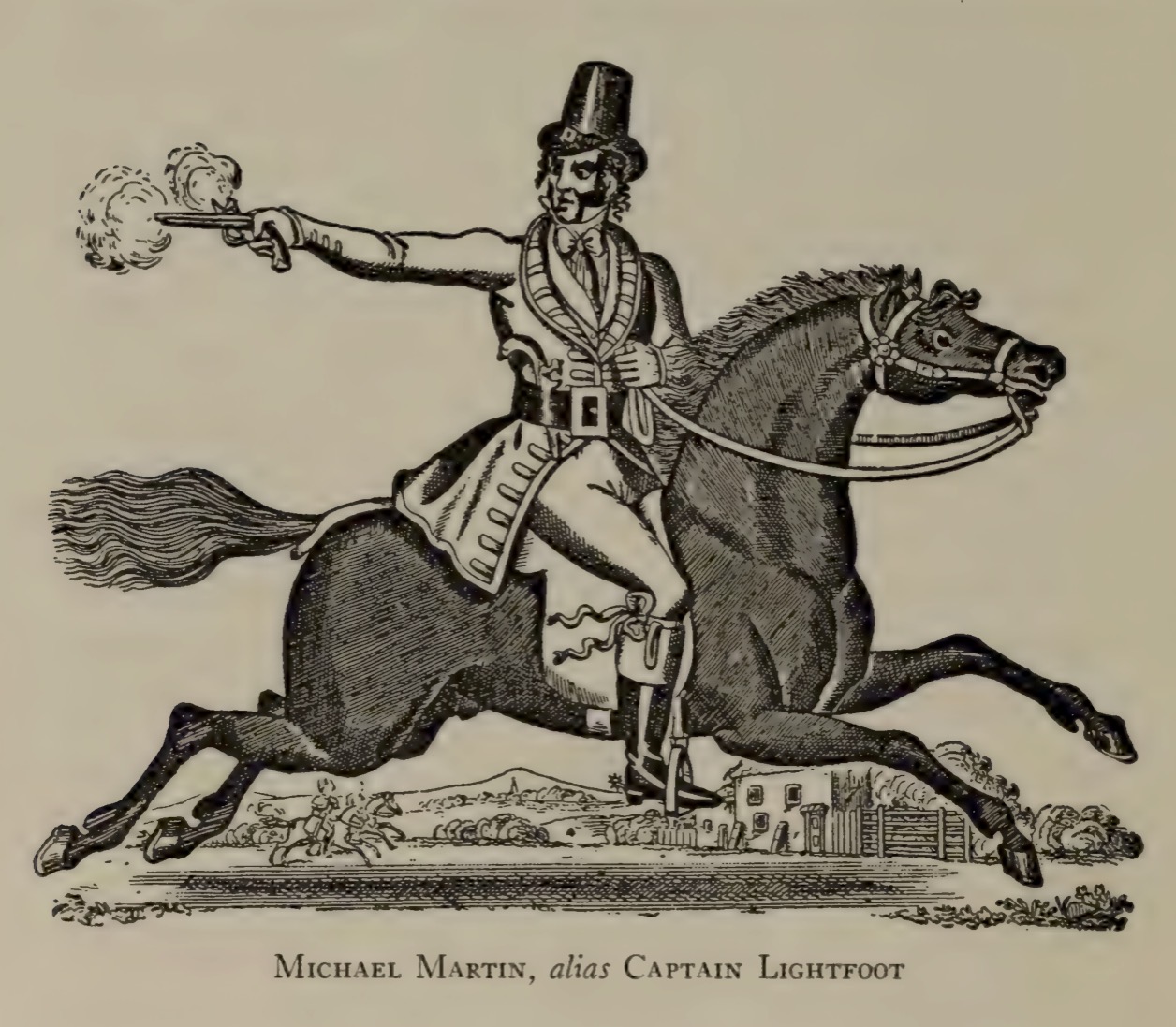

At the heart of this new, more aggressive imperialism were the East India Company and its most visible spokesman, Robert Clive. Son of a provincial lawyer, Clive was a self-made man of the least admirable kind. Haughty, manic-depressive, and very, very ambitious, he got his start as a company clerk, helping to bring the silks and spices of southern Asia to the precocious consumers of the North Atlantic. By midcentury, the company had begun to take advantage of the weakening Mughal grip in Mysore, the Coromandel Coast, and Calcutta, the major port of Bengal. When the nawab (Muslim ruler) of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, briefly seized that city in 1757, Clive seized the day, retaking Calcutta at a time of global military malaise for British arms. In 1761, Robert Clive became Baron Clive—a merely Irish peerage, he complained, but a major honor all the same. Three years later, a company force won the decisive Battle of Buxar, solidifying British control over northern and eastern India. Never one for subtlety, Clive wrote to his nominal superiors about future dominion over the entire subcontinent.

After the beleaguered Mughals handed Clive the diwani, or civil administration and land revenues, of Bengal and the nearby provinces of Bihar and Orissa, the Baron returned to Britain in pomp and splendor. Rumors circulated that he carried egg-sized gems from the east, and in fact he had profited as few imperialists before and many since from a combination of gifts, bribes, and sheer plunder. (He later compared the riches he found to a beautiful but married woman who tried to seduce her husband’s friend; eventually, any man would give in to the entreaties of “flesh and blood.”) Still, Clive could not shake his parvenu insecurities. So he chased more wealth, more power, more honor. He and other company officials set off a boom in East India stock from 1766 to 1769, and when this bubble burst, public suspicions about the “nabobs” (corrupted from nawab) returning from the east intensified. In early 1772, with the company’s finances in shambles along with its reputation, Parliament resolved to find out what was happening on the far end of the empire. Clive answered charges of misrule and corruption with his signature grandiloquence, appealing to “my Country in general” to restore his good name.

When red-blooded Britons like Clive boasted of their liberties, they did have a point. Compared to the Frenchman or Hessian of the day, the average Englishman was not only safe from arbitrary arrest but also free (and able) to read unflattering things about his government. The sheer amount of circulating ink—newspaper sales reached 12 million in the 1770s—established de facto freedom of the press even as libel and sedition laws undercut its de jure status. And beginning in March 1772, the testimony of Lord Clive and many other witnesses hit the London streets. The London Chronicle and other papers reprinted the report in segments, while the Evening Post sold the findings as a single volume: The Minutes of the Select Committee Appointed by the House of Commons, to Enquire into the Nature, State, and Condition of the East India Company, and of the British Army in the East Indies. Two books and many pamphlets on the subject also came out that spring and summer, while a new play, The Nabob, opened in theaters. So Clive was right: he was testifying to his country in general. Among the many Englishmen who listened and read over the next year was Thomas Paine, just arriving in London to find readers for his petition.

By any measure, the stories that turned up were horrifying. The collapse of Mughal rule and the onset of civil government by a for-profit corporation made an ideal milieu for corruption, venality, and violence. Failed rains in late 1769 and 1770 triggered severe hunger in Bengal, and when company agents disrupted both the production and distribution of rice—in some cases profiting from the sudden spike in the price of calories—crisis turned into catastrophe. Several million people perished. Witnesses spoke of bodies clogging the streets, contaminating the rivers, and satiating the birds and rodents. In testimony to Parliament in May 1772, Major Hector Munro discussed his handling of a mutiny among the native soldiers, or sepoys, serving under him eight years before. Four at a time, the mutineers were marched to the front of his assembled troops, tied to the mouths of cannon, and “blown away.” In all, twenty-four sepoys went up in gun smoke and gore. None of Munro’s listeners in Parliament questioned these tactics, although they did wonder about his pay. One even noted the “merit” of his service.

Perhaps the image of two dozen noncompliant natives being pulverized somehow reminded Paine of his Quaker kin, long despised for their refusal to bear arms. Perhaps he saw parallels between his own work as revenue collector and the calamities brought on by the diwani. Or perhaps his brief tenure aboard a privateer fifteen years earlier alerted him to the physical agonies of hunger and whipping. Human empathy is a mysterious thing; no one knows why it sometimes breaks through the usual mesh of self-interest and apathy. In any case, shame and embarrassment, if not empathy, were plentiful in London during the spring and summer of 1772. “Oh! my dear Sir, we have outdone the Spaniards in Peru!” Horace Walpole wrote to a friend in March. “We have murdered, deposed, plundered, usurped—nay, what think you of the famine in Bengal, in which three millions perished, being caused by a monopoly of the provisions by the servants of the East India Company?” In April, Walpole imagined the later-day ruins of Lord Clive’s fabulous home, a future relic of Britain’s decline into luxury and “famine at home.” The company was a spectacular qualifier to the national narrative of civility, not to mention a four-alarm look at corruption in high places. As the insufferable title character of The Nabob scoffed when warned about God’s vengeance, “This is not Sparta, nor are these the chaste times of the Roman republic.”

In part, the public outcry of 1772 was about Clive, a man who had grown too big for his own good, and about the “nabobs” returning from South Asia, who were widely seen as fops and upstarts. In part, it was about the East India Company, which had pushed the country into financial and military commitments around the world. And in part, it was an early act of a recurring imperial drama, whereby the violent reality of colonial imposition returns “home,” upsetting the nice narratives that normally shelter an empire’s citizens from its deeds. As we all know, however, the bloody crimes of imperial actors do not readily undermine the wider projects they serve. The anachronistic comparison is unavoidable: the conduct of Blackwater Worldwide in Iraq—as revealed in the September 16, 2007, bloodbath in Nisour Square, Baghdad—did not prompt any fundamental questioning of the American presence there. Instead, blame (and charges) fell on a few bad apples or on a general milieu of chaos with origins too complex to consider.

Likewise in Britain during 1772, a brief period of naïve shock was followed by the long, easy labor of disowning and forgetting. If the wrongdoing centered on the company, not the empire, then Parliament could tidy that up with new regulations (plus a bail-out that would spark a tea party in Boston the following year). If the evildoers could be named, then the wider networks of power they obeyed could be cleared. The very term nabob coded these men as foreign and exotic, corrupted, as Edmund Burke would later say, by long exposure to “Muhammadan tyranny.”

In May 1773, after much sound and fury, Parliament scolded Clive for his extravagance but also commended his “great and meritorious service to this country.” The exposés of plunder and murder came and went, and the imperial consensus held. However tarnished, Clive emerged free, rich, and famous—a hero, more or less. Meanwhile, Paine’s petition for better pay to excise officers was not so much refused as ignored. After carrying it around London, looking for an audience with Parliament, Paine gave up on this first venture into political activism in early 1773. And while Clive set off on a grand tour to Italy, hoping to burnish his aristocratic credentials, Paine’s life unraveled. By the fall of 1774, he had lost his excise post, sold his property, and separated from his second wife.

We have little record of Paine’s feelings and opinions before 1775, and thus no starting point from which to measure the extent of his alienation. Apparently, though, the crush of events in 1772 and 1773—his approach to Parliament, his exposure to East Indian atrocities, and the simultaneous rebuff of his petition and vindication of Robert Clive—worked like acid on whatever sense of Britishness he carried, eating away at inherited ties to king and country. Apparently, the hard memory of personal failure attached itself to the galling thought that no one had been punished for blowing away those innocent natives. Paine boarded a ship to Philadelphia in late 1774, carrying a valuable letter from Benjamin Franklin and a gathering fury at the empire.

On November 22, 1774, while Paine was still at sea, Robert Clive committed suicide. After arriving and landing a job at the Pennsylvania Gazette, Paine took up his pen with all the freedom and vigor that distance from London allowed. “Reflections on the Life and Death of Lord Clive,” published in March 1775, introduced Philadelphians to the ugly truths of empire. Blending Christian ethics and Swiftian j’accuse, the article memorializes slain Asians more than the departed Clive. “But, oh India! thou loud proclaimer of European cruelties, thou bloody monument of unnecessary deaths, be tender in the day of enquiry, and shew a Christian world thou canst suffer and forgive.” Clive’s lust for power and dominion, Paine explained, had crashed like a storm upon the people of Bengal, whom he represented as a widow and orphan. Wherever Clive and the East India Company had ventured, “murder and rapine” had followed, with “famine and wretchedness” not far behind.

With “British Sword” in hand, Clive had bullied and bribed the natives, treating them as nothing more than stepping stones to “an unbounded fortune.” He had then returned in glory to a fatuous nation, Paine continued. Yet the bloody deeds had reappeared in the newspapers like “specters from the grave,” whispering “murder” and demanding justice. Discredited and forgotten despite his acquittal, Clive had fallen ill and wandered the streets of London, where he was mistaken for a ruined beggar. “Hah! ’tis Lord Clive himself!” Paine imagined the city’s downtrodden having said. “Bless me what a change!” The reborn ex-pat taunted the dead imperialist: “A conqueror more fatal than himself beset him, and revenged the injuries done to India.” In addition to its warnings of supernatural judgment, what is most striking about Paine’s early work in America is its repeated condemnation of military violence and conquest, as distinct from monarchy or aristocracy.

What did Paine read or hear of the first clashes between British regulars and Massachusetts colonials in the spring of 1775? How did he process the news of bloodshed within his adopted country? It seems reasonable to begin with the four reports that arrived at his magazine’s office on the afternoon of April 24, 1775, five days after the fighting broke out. These spoke of thirty to forty Massachusetts militiamen, “innocently amusing themselves” on Lexington green, facing down one thousand British redcoats, who then opened fire “without the least provocation.” One dispatch said that some of the Americans had taken refuge in the town church, whereupon the redcoats “pointed their guns in and killed three.” Another reported that the British had searched for rebel leaders at their homes “and not finding them there, killed the woman of the house and all the children, and set fire to the house.” They then marched on, “firing and killing hogs, geese, cattle, and everything that came in their way, and burning houses.” Blending fact and fear, these reports recalled for Paine, not the veiled absurdity of hereditary rule, but the crying obscenity of imperial violence.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1775, Paine was clearly frustrated at American caution and reluctance. His Quaker brethren, in particular, clung to what he saw as hard-hearted loyalty to the king. Although “a Lover of Peace” and “thus far a Quaker” himself, Paine wrote, he could neither understand nor abide their refusal to see this “ruffian” enemy for what it was. The British, he announced, “have lost sight of the limits of humanity,” and yet the Friends spoke of reconciliation. Even the hot-headed rebels from Boston paused on the brink, reiterating their fealty to George III and their claims to the British constitution. Deference to British civilization died hard, even—or perhaps especially—for American provincials who were never sure if they were fully British. As late as 1774 and 1775, most Americans wanted, in some important sense, to be Britons. It was Paine, the recent émigré, who was most willing to denounce the empire itself rather than its corruptions.

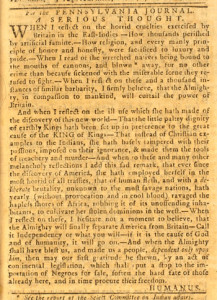

His October 1775 essay, “A Serious Thought,” fairly shouted at his readers to wake up to their peril. “When I reflect on the horrid cruelties exercised by the British in the East-Indies,” he proclaimed, and “read of the wretched natives being blown away, for no other crime than because, sickened with the miserable scene, they refused to fight—When I reflect on these and a thousand instances of similar barbarity, I firmly believe that the Almighty, in compassion to mankind, will curtail the power of Britain.” The atrocities in South Asia were the most recent and relevant clues as to British intentions. And they had gone unpunished, mocking the sovereignty of nature’s God over the moral world. Paine’s “Serious Thought” went on to report that the British had also “ravaged the hapless shores of Africa, robbing it of its unoffending inhabitants to cultivate her stolen dominions in the West.” Plunder and atrocity followed the British sword as night followed day.

All of which helps to account for an opening passage of Common Sense, which otherwise exaggerates the extent of British violence in North America as of December 1775. “The laying a Country desolate with Fire and Sword, declaring War against the natural rights of all Mankind, and extirpating the Defenders thereof from the Face of Earth, is the Concern of every Man to whom Nature hath given the Power of feeling.” The abuses you have suffered are no anomaly or corruption, Paine told his readers. They were the means the empire would use to reduce you to subservience, so that it could plunder the country at and for its pleasure. This time, he did not mention the East Indies by name, turning instead to graphic generalities. “Thousands are already ruined by British barbarity; (thousands more will probably suffer the same fate).” Yet the warning about “Fire and Sword,” rooted in his understanding of imperial history, shaped the argument of Common Sense at every crucial point. The colonies could not reconcile with the Crown, nor trust its military, because British ships and redcoats were threatening the people with murder most foul. The colonists should not forgive Britain as the so-called mother country because any kinship only made the crimes more appalling.

In addition to exploring the origin of Jewish royalty, the actual strength of the Royal Navy, and the future market for American exports, then, Common Sense points the reader to atrocities past, present, and future. It is a warning siren on British cruelty. Referring, by footnote, to the “Massacre at Lexington,” Paine also cites “that seat of wretchedness,” Boston, where a trapped population was left “to stay and starve, or turn out to beg.” Besieged by their own people and “plundered” by the British occupiers, they lived in fear of “the fury of both armies.” As for George III, he was a wretch, a brute, a “sullen tempered Pharaoh” who shrugged off the “slaughter” of his subjects. Paine’s most startling message was not so much independence as the pressing reason for that course: the British were vandals and brutes, their empire evil and insatiable.

Paine stayed on point with his “Forrester” letters, written as Common Sense spread through the colonies in the spring of 1776. Responding to a Tory writer known as Cato, Paine referred again to “the havoc and desolation of unnatural war … the burning and depopulating of towns and cities.” When Cato warned that rebellion would bring foreign troops to American shores, Paine pointed once more to the appalling reports from 1772. “Were they coming, Cato … it would be impossible for them to exceed, or even to equal the cruelties practiced by the British army in the East-Indies: The tying men to the mouths of cannon and ‘blowing them away’ was never acted by any but an English General, or approved by any but a British Court*—read the proceeding of the Select Committee on India affairs.” (The endnote: “*Lord Clive, the chief of Eastern plunderers, received the thanks of Parliament for ‘his honorable conduct in the East-Indies.'”) The juxtaposition of British rhetoric and British cruelty became a staple of Paine’s work, a favorite way to foster disgust with his former rulers.

As British and Hessian troops did what invading armies usually do in New Jersey and Pennsylvania in late 1776 and 1777, Paine’s pen flowed on, recording the history he had foreseen. King George III, he wrote in January 1777, sought “to lay waste the world in blood and famine … to kill, conquer, plunder, pardon and enslave.” Instead of “civilizing” the world, he fumed the next year, Britain had opted “to brutalize mankind.” As the months went by and the war dragged on, Paine widened the circle of blame. “She is the only power who could practice the prodigal barbarity of tying men to mouths of loaded cannon and blowing them away,” he suggested of Britain. No longer the burden of Lord Clive or King George III alone, the sins of conquest fell upon the nation itself. Under “the vain unmeaning title of ‘Defender of the Faith,’ she has made war like an Indian against the religion of humanity.” (Here, “Indian” referred to the indigenous Americans for whom Paine never showed much sympathy.) The island seclusion of the British people, Paine came to suspect, had sheltered them from the bloodshed they inflicted around the world. But someone—God, Europe, world opinion—was watching and keeping score. “Her cruelties in the East-Indies,” he vowed in 1778, “will never, never be forgotten.”

“If I have any where expressed myself overwarmly,” Paine announced during the War of the American Revolution, “’tis from a fixt immovable hatred I have, and ever had, to cruel men and cruel measures.” We can safely say that Thomas Paine sometimes expressed himself overwarmly. The roots of his righteous fury, on the other hand, are elusive, for like any essential feelings they are the singular possessions of minds unlike our own. In Paine’s case, though, that “fixt immovable” sentiment clearly involved the revelations about South Asia that came to London in 1772. From then on, whenever he attacked “government” in general and British rule in particular, he had in mind not only the formal apparatus of the state but also the appalling crimes done to Bengal. From then on, he recalled Lord Clive, resting his case before a fawning Parliament, or Major Munro, reporting with a shrug that sometimes, in the line of duty, a commander had to blast mutineers from cannons. Paine carried his rage into the global tumults of the 1780s and 1790s, eventually inviting the Irish to rise up against his homeland and the French to invade it.

Back in London, imperial atrocities kept coming home. In 1783 and 1784, unsettling reports arrived from Mysore, including an account of four hundred “beautiful women” who were killed, injured, or raped by British soldiers. Edmund Burke and other statesmen were shocked, just shocked, and they passed another set of regulations that reined in the company while legitimizing the empire. In 1806, London learned that the governor of Trinidad, just taken from Spain, had ordered the torture of a mulatto girl accused of aiding a robbery. More shock and scandal, more sound and fury, and another storm that blew over. Increasingly after the 1818 publication of The Practice of Burning Widows Alive, an exposé of suttee, Europeans began to replace Enlightenment-era critiques of imperial barbarity with Victorian assumptions about South Asian, Chinese, and Islamic barbarity. The white man’s burden was to end such customs by force if necessary, dragging the dusky races to Christianity and Law and Progress and so on.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, memories of imperial violence helped to form the self-concept of new nations around the globe. They made up the popular core of one of the modern world’s defining ideologies: anti-colonialism. Irish citizens recall the “Bloody Sunday” of 1972 and the even bloodier “Troubles” of the 1910s; Indians memorialize Jallianwala Bagh, a walled garden in the northern city of Amritsar where British troops killed 379 unarmed people on April 13, 1919. In these cases and many others, the specific killings evoke a lasting captivity, a national experience of long humiliation and final emancipation. To recall these atrocities was, and is, to recall suffering in its most basic form—not a political grievance but the galling fact of physical domination and destruction.

Because they broke away from European empire so early in the world-historical scheme of things, American citizens did not have to cope with such memories. They did not have to think of themselves being tied to cannons and blown away. The full horror of imperial dominion had never fallen upon them, the atrocities of the two Anglo-American wars notwithstanding. Even in the Revolutionary era, much of the suffering was virtual, imagined through tales from far-away lands and far-off times. By the mid-nineteenth century, as they rationalized the taking of native lands by defining native peoples more as vagrants than sovereigns, American citizens could disown both the guilt and the humiliation of empire. They could take pride in the belief that they had never been imperial villains orcolonial victims. Instead, they had broken away because of a constitutional and political dispute, because of unfair taxes and poor representation. As for references to British crimes in India and elsewhere, these disappeared as the foreign policies of the English-speaking powers began to align after the 1820s.

As we continue the work done by Carl Becker to break down and see through this tame narrative of national creation, then, we should be careful to recall the awful violence it conceals, the nameless victims it forgets. We should take eighteenth-century fears of plunder and famine as seriously as those of “conspiracy” and “slavery,” tracing out the specific accounts and stories that informed popular reactions to imperial impositions. In that way we might learn something, not only about how to teach the American Revolution, but also about how to consider the crimes and redactions of our own times.

Further Reading:

Historians continue to gain new insights into Thomas Paine, connecting his ideas to the larger histories of democracy, nationalism, human rights, and international relations. See, recently, Nicole Eustace, Passion is the Gale: Emotion, Power, and the Coming of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2008) and Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations (New York, 2006). For relevant studies of imperial violence and its domestic fallout, see Nicholas B. Dirks, The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain (Cambridge, Mass., 2008) and James Epstein, “The Politics of Colonial Sensation: The Trial of Thomas Picton and the Cause of Louisa Calderon,” American Historical Review 112 (June 2007): 712-41.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.4 (July, 2009).

J. M. Opal is associate professor at McGill University and the author of Beyond the Farm: National Ambitions in Rural New England (2008). He is working on an edited collection of Paine’s writings and influences, to be published by W. W. Norton and Company, and on a new book about Jacksonian Democracy and vengeance in American public life.