The Curious Case of the 1670 Deed to Aquehonga Manacknong

Staten Island is the least populated part of America’s most populated city, hence its self-pitying nickname: “the forgotten borough.” But when it comes to its Native past, perhaps it is really the forgetting borough. There are no indigenous place names currently used on the island, which makes it unique among all counties in the greater New York City area.

This erasure may be evidence of its contested past, as the colonists who bought it were rather glad to see the Natives go. Dutch and English colonists spent forty years trying to claim the island. Unsurprisingly, the messy history of its purchase is overshadowed by legends of the more celebrated island to the north. But here the oddball borough has Manhattan beat, as it has a more compelling story to tell of how it was bought and sold.

From land papers, we know that Indians most often called the island Aquehonga Manacknong, a name that likely meant “the place of bad woods.” (The name also suggests the borough’s inferiority complex goes back a long time.) In keeping with the place’s characteristic amnesia, we don’t even know what the island’s Native residents called themselves. At different points in the colonial period, communities on the island were politically linked with the Hackensack, Tappan, Raritan, Manhattan, and Rockaway peoples. But no colonist recorded a proper name for just the islanders. One acceptable but broad term for the people of Aquehonga Manacknong is Munsee, which is a later name for dialects spoken near the lower Hudson. Today, the descendants of Munsee speakers also identify as Lenape or Delaware.

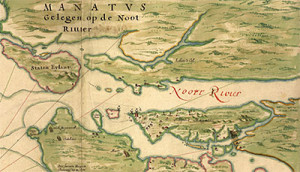

The Dutch, who began colonizing the region in the 1620s, admired the hilly mass that guarded one of the best natural harbors on the continent. They named it after the Staten-Generaal, the assembly that united the seven Dutch provinces and was the highest sovereign body in their monarch-less republic (fig. 1). Although the Dutch made an initial purchase of the island in 1630, they did not get around to making a permanent settlement until 1639. The early European buildings were abandoned in local wars that broke out in 1641, then again in 1655. Though Natives signed a second deed to the island in 1657, it was annulled months later when the Dutch purchasers failed to deliver the goods promised for the land.

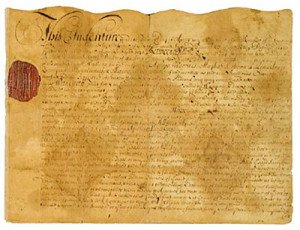

The 1670 deed that finally ended indigenous claims now rests several miles from the actual island, in a small cache of Staten Island papers at the New-York Historical Society on Central Park West (fig. 2). As the document that officially made Staten Island part of New York and not New Jersey, it is an undeniably significant text. But it is also an unusual text, containing seldom-seen details of how Native communities negotiated over land. When read closely, the 1670 deed challenges our tendency to see deeds as merely evidence of Indians’ capitulation to colonial rule. While the document reveals a painful process of dispossession, it also shows colonists reconciling their legal practices with Native traditions in peculiar ways.

Before getting to this piece of evidence, it helps to consider the larger history of Indian land sales, starting with the tale of Dutchmen buying Manhattan for a mere twenty-four dollars’ worth of trinkets. There is a grain of truth in this apocryphal story. A 1626 document reported that Pieter Minuit offered the Manhattan people sixty guilders of unspecified goods as compensation for the Dutch West India Company’s initial occupation of the island’s tip in either 1624 or 1625. First calculated by a nineteenth-century historian, the $24 price then made its way into schoolbooks. The myth of Manhattan’s price makes an irresistible origin story for the capital of capitalism. It tells us that the Big Apple was the home of predatory business deals from its very start. Whether seen gleefully or cynically, this smug little story assures us that Westerners were crafty while the indigenes were naïve.

Americans generally take Native history more seriously today, but we haven’t retired all our simple myths about Indians and land. Many make the common assumption that Indians did not believe territory could be sold, while colonists obviously did. It is true that Natives and Europeans had drastically different uses for land, and mutual misunderstandings about real estate transactions were common. But the idea that Natives were incapable of seeing land as a transferable property is a kind of Noble Savage hokum that insists Indians had a spiritual reverence for every square inch of soil, and thus barely made a mark upon the earth. When repeated uncritically, the idea that indigenes were incapable of imagining territory as property is a crude caricature of Natives’ diverse cultural beliefs that erases thousands of years of actual indigenous land use. In fact, Indians across the continent transformed the natural world to their liking, marked extensive territorial boundaries, and consecrated their lands with their buried dead. And many Native leaders agreed with colonists that at least some tracts (especially those without sacred significance) could be bounded, transferred, or leased. As early as 1643, the English colonist Roger Williams pointed out that his Narragansett neighbors were “very exact and punctuall in the bounds of their Lands … I have knowne them make bargaine and sale amongst themselves for a small piece, or quantity of Ground.” He argued that anyone who denied this fact was advancing the “sinfull opinion among many that Christians have right to Heathens Lands.”

Another widely held belief is that most deeds were the products of outright trickery or intimidation. It is true that white land agents drew up fraudulent papers, lied about their deeds’ terms, and tried to garner the signatures of intoxicated or unauthorized sellers. But far more often, the real swindle came from lopsided economics and demographics. There was an inherent imbalance when hunting-and-farming gift-centered societies that were suffering devastating population losses from disease did business with growing colonial societies connected to a global web of trade that gave them a much broader selection of technology and wares. When we calculate prices in European currency, we erase the Native perspective on what they were “actually” being paid. And there was always the looming specter of violence. Although colonists seldom made explicit threats when orchestrating legal transfers of territory, and the text of deeds often championed peace and coexistence, there remained the possibility of illegal incursions or bloodshed if the papers were not signed. Chicanery and coercion were certainly part of the process, but seldom blatant.

The 1670 Staten Island deed and the minutes of negotiations show in detail how these transfers worked. Though the papers document a Native loss, they also are evidence of a forty-year process of contestation, and more than a week of face-to-face negotiations. In the years before the deed was written, colonists had been hounding the islanders to renegotiate the twice-voided sale. The foreign population was booming, and the English colonists who had evicted Dutch officials in 1664 were looking to establish clear title to the best lands near Manhattan. The Munsees found colonists to be bad neighbors, since Europeans’ free-roaming livestock trampled Native cornfields. Looking to resolve Indian complaints and satisfy colonial land hunger, New York governor Francis Lovelace invited the island’s chiefs, or sachems, to work out a full sale that spring.

Talks commenced on April 7, 1670, a day later than planned, as “Windy Weather” kept the first Native parties from crossing the bay. The negotiations began haltingly, as not all of the five leading sachems of Staten Island were present, so the colonists had to wait another two days while the full delegation took shape. In the first meeting, the new English leaders produced previous deeds from the Dutch archives, to support their side of the negotiations. In doing so, they made an offensive mistake when they “demanded” if the present sachems “have heard of the names in the Dutch Records, of wch diverse were read to them.” Perhaps just then a chill went over the proceedings while the islanders exchanged pained looks, for the Indians answered, “some they remember, but they are dead, so [the sachems] doe not love to heare of them.” In reading the names out loud, the colonists had accidentally broken the Munsee taboo against speaking of names of the deceased. Still, the sachems were willing to forgive the transgression and work out a sale, provided that “a Present shall bee made them some-what extraordinary for their Satisfaction.”

Native and colonial officials met several times over the next six days, working out the details of this gift. The initial offer of clothing, tools, and munitions was deemed not “extraordinary” enough. And there was no wampum: the sacred shell beads not only functioned as a cross-cultural currency, but were also highly valued as decorative jewelry and a symbolic gift by Indians. The Munsee delegation returned with a request for six hundred fathoms of the beads, the colonists counter-offered only half that; finally they all settled on four hundred fathoms. (Each “fathom” could contain between 180 and 300 individual wampum beads, meaning the entire exchange contained between 72,000 and 120,000 beads.) While wampum’s value in European coins had been declining for decades, this was still a substantial sum—the beads alone far surpassed the first price paid for Manhattan nearly fifty years earlier. In a similar back-and-forth, the Indians convinced the colonists to triple the amount of clothing offered, and significantly increased the gifts of guns, lead, powder, hoes, and knives.

On the thirteenth of April, the colonists drew up the deed. The resulting document—three buff-colored parchment pages, covered in fine calligraphic writing, and bearing the colony’s red wax seal—was far longer than most land papers, and its first curious feature appeared on the signature page. Four additional names were offset from the names of the governor, the mayor, and eight members of the colonial council. Two of them (William Nicolls and Humphrey Devenport) were English, the other two (Cornelis Bedloo and Nicholaes Antony) were Dutch. A notation to the side identified these signatories as “4 Youths.”

These were apparently the sons of council members or the previous governor Richard Nicolls. No minutes indicate why exactly the young men were asked to sign this text, but the practice of bringing in the next generation to witness agreements had some precedent. Just three days earlier, Governor Lovelace signed an agreement with an Esopus Indian sachem from farther up the river, who had brought along “his young Son and another young Indyan” to “sett their hands” on an older peace treaty, and the Governor “admonished” the Esopus sachems “to Continue the same Custome yearely.” Though the English were insisting upon these annual meetings, the practice fit rather well with Native diplomatic customs, which favored the regular renewal of previous agreements.

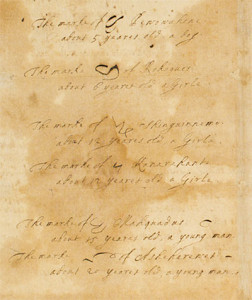

A similar clause appeared on the 1670 Staten Island deed. In an addendum on the final page, several sachems agreed that they “shall once every Yeare upon the First Day of May yearely after their Surrender repaire to this Forte to Acknowledg their Sale of the said Staten Island to ye Governour or his Successors to continue a mutual friendship betweene them.” Even more extraordinary was another short memorandum written two days after the original signing, written on the back of the first page (fig. 3):

Memorand. That the young Indyans not being present at the Insealing & delivery of the within written Deed, It was againe delivered & acknowledged before them whose Names are underwritten as witnesses April the 15th 1670

The marke of X Pewowahone about 5 yeares old a boy

The marke X of Rokoques about 6 yeares old a Girle

The marke of X Shinguinnemo about 12 Yeares old, a Girle

The marke of X Mahquadus about 15 yeares old, a young Man

The marke X of Asheharewes about 20 Yeares old, a young man

The Xs mark the actual penstrokes. The signatures of Pewowahone and Rokoques, the kindergarten-aged boy and girl, are so dark they can be seen on the other side of the thick page. It seems the children, perhaps having their hands directed by an adult, moved the pen so slowly that excess ink bled through. All the young signers’ marks are but twisted lines, their meanings unclear. By contrast, the marks of Native adults on many other deeds were recognizable pictures of animals, weapons, and people.

It is a strange thing to see the writing of small children—and half a dozen adolescents—on a momentous legal document. And it is even more mystifying that no one at the time noted who decided to call children as witnesses and why. Yet as unusual as these actions were, there are some likely reasons both parties would want to involve their young. For colonists frustrated at having to buy the same piece of land three times in forty years, the marks of those four colonial boys and five Munsee youths would prevent any further Indian claims from surfacing later. But even if we assume that including Native children signatories was a colonial idea meant to protect their property, the act served Native interests as well. No Indians wanted to repeat the upsetting moment of the previous week, when colonists spoke the names of the dead. Having a five- or six-year-old’s mark on the treaty made it more likely he or she would be alive to affirm the agreement for decades into the future.

Moreover, Munsee people had long been dedicated to teaching their children about politics and history. More than two decades earlier, in the midst of the horrific Dutch-Native war known as Kieft’s War, sachems who left a failed peace negotiation made it clear that this moment would live on. While criticizing the New Netherland director Willem Kieft for his insufficient gifts, the Munsees remarked that he “could have made it, by his presents, that as long as he lived the massacre would never again be spoken of; but now it might fall out that the infant upon the small board would remember it.” The same principle seemed to be at work among the Staten Island Indians. Neither Pewowahone nor Rokoques would easily forget the childhood memory of signing that parchment.

Perhaps there are other incidents like this silently chronicled in the many thousands of seldom-read and yellowing land deeds sitting in American archives. But even if it is an outlier, the sale of Aquehonga Manacknong confirms a larger point that many scholars are making about Native land loss. We have long known it was more than just an economic or military matter, but now we are truly starting to grasp the complexity of what happened when Natives and colonists did business. Seemingly unrelated cultural matters like the taboo of speaking of the dead or the ways Native parents taught their children history were crucial to forging an agreement over land. And in its peculiarities, the 1670 deed shows that the Natives who sold Staten Island were hardly defeated dupes. It is a page out of the forgotten borough’s past well worth remembering.

Further Reading

For more on the $24 myth see Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York, 1999). On Staten Island placenames, see Robert S. Grumet, Manhattan to Minisink: Native American Placenames in Greater New York and Vicinity (Norman, Okla., 2013). There have been several new books on Munsees and their dealings with the Dutch and English in just the last few years. Robert S. Grumet takes a close look at land sales in The Munsee Indians: A History (Norman, Okla., 2009), while Tom Arne Midtrød examines diplomatic practice along the Hudson in The Memory of All Ancient Customs: Native American Diplomacy in the Colonial Hudson Valley (Ithaca, N.Y., 2012). Susanah Shaw Romney compellingly explores the central role of women and larger family networks in Dutch-Native relations in New Netherland Connections: Intimate Networks and Atlantic Ties in Seventeenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2014). For a cultural reading of land transfers and the way Native peoples thought about space on a broader scale, see also Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (Minneapolis, Minn., 2008) and Jeffrey Glover, Paper Sovereigns: Anglo-Native Treaties and the Law of Nations, 1604-1664 (Philadelphia, 2014).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.2 (Winter, 2015).

Andrew Lipman will be joining the history department at Barnard College, Columbia University, this fall. Previously he taught at Syracuse University and was an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Long-Term Fellow at the New-York Historical Society. His first book, The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast, is forthcoming from Yale University Press.