I begin with a paradox: After the Civil War, middle-class white women increasingly assumed public roles in cultural, political, and economic arenas, but their achievements were rarely depicted in the illustrated press. In the engravings of popular pictorial weeklies such as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, women were typically represented as victims, criminals, workers in manual trades, denizens of the household, or shoppers. The rare appearance of female professionals, politicos, and culture workers begs explanation. Even on those occasions when middle-class white women were shown, they were rarely depicted as working professionals or assertive public figures. With the exception of cartoons, most of the illustrations of these women were static and constrained—portraits, rather than the rich narratives that characterized other illustrations.

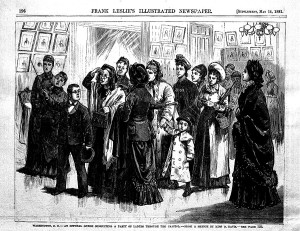

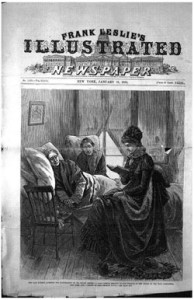

This tendency to visually exclude active, working, middle-class white women obscured the uncomfortable fact that increasing numbers of white, middle-class families relied on the material contributions of their wives, sisters, and daughters. The work of Georgina A. Davis, an engraver and staff artist for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, illustrates the conventional depictions of middle-class women. But it also suggests ways at least one professional woman attempted to challenge these conventional depictions. An 1881 illustration by Davis is an example of the paradox I am describing (fig. 1); can you identify the artist-reporter in the picture?

Davis’s signature appeared over one hundred times in her first decade at Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1880-1890), making hers a familiar name to readers. As a staff artist at a major nineteenth-century illustrated weekly, Davis’s career was not at all typical for women working in commercial art. Although many other women artists contributed to the illustrated press as free-lancers, Davis’s longevity and permanent staff position more closely resembled male artists’ careers. By the time Frank Leslie’s accepted her first illustration in 1880, Davis was already an established painter and engraver. Her first critically noticed illustration, “The Bridge of Sighs,” appeared in 1872 in the art journal the Aldine and later found a place in the Women’s Pavilion at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

That the earliest critical attention Davis received referenced Thomas Hood’s popular poem, also entitled “The Bridge of Sighs,” presents us immediately with the limitations artists faced in representing women’s work. The poem describes the discovery of a deceased young prostitute. The fallen woman in Hood’s poem follows a narrative trajectory—from wronged and seduced, to sinning and wrong, to suicide as righting all wrongs—that painters and illustrators of this era drew on to create a visual vocabulary of female victimization. As the embodiment of lost respectability and purity, the figure of the prostitute pointed to the particular dangers women faced in the modernizing, commercial city.

Additionally, for women’s rights supporters, the fallen woman dramatized the problem of female dependence and the scarcity of lucrative and respectable occupations for women. One widely advocated solution to these problems was training in art and design. Beginning in the early 1850s, schools of design for women were established in New England, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York to prepare female artists for employment in manufacturing and publishing. The founders of these design schools hoped to create opportunities for women to work at “congenial pursuits,” while elevating the design of American manufactures, thereby solving two distinct yet related problems: the dilemma of female self-support (always aligned with maintaining female purity) and the presumed inferiority of American art and design. In a familiar republican combination, maintaining women’s purity was part of the prescription for maintaining national ideals. And in reducing women’s material dependence on others, design schools would also help to eliminate national dependence on European art and design. The dissemination of art through print culture and art education dedicated to enhancing the design of manufactured products also promised to elevate popular taste and sustain democratic values.

At the Cooper Union Female School of Design (the name of the New York School of Design for Women after its adoption into Peter Cooper’s great experiment in free education for mechanics in 1859), Georgina Davis studied with women who intended to become self-supporting artists and engravers as well as with women for whom art would remain an avocation. Although tuition was free for industrial pupils (those who intended to work), the classes were during the day when less financially secure working women were unable to attend. Those who could attend typically included women from the families of farmers, ministers, engravers, clerks, and merchants. Their fathers and brothers assumed that if they remained unmarried, these sisters and daughters would need a respectable career path. Unlike the starving seamstress or the prostitute, both represented as victims of male commercial culture, the women trained as designers, wood engravers, and illustrators represented a new, respectable, potentially comfortable form of female industry.

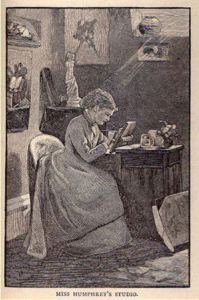

The distinctiveness of this new form of female work is suggested by two engravings. The first, an 1868 Harper’s Bazar double-page engraving of “Women and their Work in the Metropolis,” featured a sleeping seamstress, cradle at her feet, at the center of a series of smaller vignettes about working women (fig. 2). The seamstress’s portrait is larger than the others, perhaps indicating the significance of sewing as a source of women’s employment; moreover, except for her child, she is shown alone and at home, unlike the surrounding vignettes—the latter depicting women working with other women in shops and factories. Compare this image to a portrait of Lizbeth B. Humphrey, an illustrator and classmate of Davis at the Cooper Union Female School of Design (fig. 3). Humphrey, pictured in her Boston studio bent to her task, her work lit by a nearly celestial beam of light, is surrounded by markers of art and culture—statuary, sketches, and flowers. Like the seamstress,

Humphrey is shown laboring in isolation; both figures’ respectability is anchored in their privacy and their domestic distance from commerce. Davis and Humphrey, as members of the first group of women to attend design schools, represented a kind of test case for self-support. Could a new kind of working woman forge a different, less dependent path for urban American womanhood while maintaining her middle-class respectability?

Midcentury women’s rights periodicals supported the emergence of this new profession for women, regularly noting the efforts of women artists and profiling their schools and organizations. The success of women artists provided a clear validation of female accomplishment and symbolized women’s independence. Some women artists, Davis among them, created new associations to support and promote their achievements, notably Sorosis, the first club for women professionals. Sorosis (drawn from the Greek for sister) gathered together women artists, physicians, editors, writers, businesswomen, and fashionable modistes in a new formation that emphasized women’s autonomy, cultural authority, and productivity. Urbane, commercial, and public, the women in Sorosis made it possible for middle-class women readers to imagine identities beyond the home.

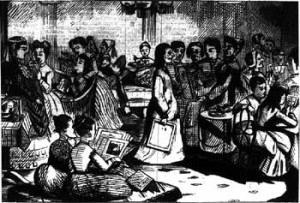

Fierce resistance to such incursions into these masculine professional and social precincts and identities forms another part of the visual iconography that structured the possibilities for representing middle-class women’s work. Cartoons in the illustrated press such as “The Ladies’ Club at Delmonico’s” dismissively lampooned the women’s professional identities and working lives, picturing them at leisure, playing cards, drinking tea, reading newspapers and avant-garde texts (hence the copy of Darwin’s Origin of the Species in the foreground), and looking at prints (fig. 4).

The advent of middle-class women as clerks in the U.S. Treasury Department during the Civil War elicited similar responses in the illustrated press. An 1869 Harper’s Bazar cartoon shows a male surprising a female work force as it studies bonnets, reads Harper’s publications, crochets, plays, and gossips (fig. 5). Identified as part of the middling classes by their reading matter (both the Bazar and Harper’s Weekly appear in the cartoon), the women clerks could not be pictured actually working outside the home.

While Davis supported women’s professional aspirations and worked actively as a commercial artist for almost thirty years, the images she made rarely depicted middle-class women at work. Whether working as a staff artist for Frank Leslie’s and the Salvation Army newspaper the War Cry, or as an illustrator for the children’s book publisher McLoughlin Brothers, there was little call for her to represent working middle-class women. Intent on portraying white middle-class women as part of a gender economy that portrayed them solely as homemakers and consumers, most iconography in the illustrated press visualized an acceptable public femininity that ignored the movement of middle-class women into the professions and other forms of paid, respectable employment. We can view the charity volunteer, the benevolent lady, more occasionally the teacher, and frequently the shopper, but the book agent, publishers’ reader, the journalist, the business woman, and the working artist are rarely glimpsed.

Davis covered “the benevolent beat” for Frank Leslie’s, reporting on charity institutions, fund-raising fairs, and various Ladies Bountiful around town—the few public venues where ladies made an unchaperoned appearance. “A Lady Visitor Reading to the Inmates of the House of the Holy Comforter” shows womanhood at its ideological best: pious, graceful, and devoted to those less fortunate (fig. 6).

The insistence on locating middle-class women in domestic settings is particularly striking given the increased visibility of middle-class women in urban public spaces. The lady in public generated a good deal of ambivalence among many observers. Her presence was evidence of changing mores as she paraded in venues that signaled pleasure and consumption, including the new urban shopping, art, and entertainment districts. In street scenes, department stores, and theaters we occasionally glimpse middle class women’s presence and

enlarged mobility in the city. But most often women are shown in these new public settings caged in interiors that recall the domestic parlor, or they are depicted in need of male protection and assistance. The dominance of these kinds of images and the relative absence of alternative visions make the forms of Davis’s self-representation interesting. How do Davis’s self-depictions subvert as well as align with this logic of constraint and control?

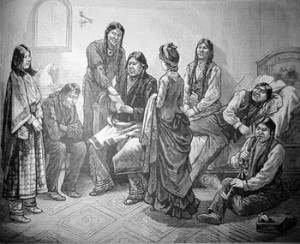

One of Davis’s first illustrations for Frank Leslie’s, “An Illustrated Interview of Our Lady Artist with the Ute Indian Chiefs and Prisoners,” in 1880 promises to present a “new” woman (fig. 7). Davis depicts the “lady artist” facing a group of Ute men, looking on as they read a document she may have presented to them. Other Ute men lounge on a bed or sit on the floor, one smoking just behind the modest walking skirt. The artist is presented in profile, neatly dressed, carefully bonneted with a shawl over one arm. She is not drawing or writing, so her identity must be inferred from the picture’s caption and the subject’s respectable dress and posture. Yet is she respectable?

The image also could be read as locating white womanhood as an integral part of a hierarchy of colonial relations of power. The artist is the only white person in a room that seems markedly homosocial and “other.” Although she remains standing, there is an air of quiet command in her attentiveness and some daring in her solo venture into what appears to be a hotel room filled with men who until recently were waging war against the U.S. government. The only other woman present is a Ute who stands apart from the group of men, also looking toward the white woman visitor. Displaying the physiognomic codes that denoted racial, ethnic, and class hierarchies in the period, the Ute woman’s coarser features, passivity, and clothing mark her as less civilized and thus subordinate to white womanhood. Nonetheless, the lady artist is snared in the gazes of at least two of those men, pinning her to her place and raising questions about her autonomy. By including herself in the illustration, Davis records her own presence and her authority as the image maker, yet she is also markedly out of place.

Compare this illustration with one Davis made during the same trip to Washington, “Social life in the national capital—An evening in the private parlors of the executive mansion” (fig. 8). In this engraving women continue to look on as men act, but the scene is decidedly domestic, tranquil, and filled with the marks of bourgeois comfort and respectability. There is no bedstead with its murmurings of sexuality; instead, the scene is anchored by the mother/child dyad at the center, bringing to the fore woman’s maternal love and woman’s place within the domestic order. The artist is not visible, making the scene a commonplace image of domesticity rather than the particular record Davis offered of the Utes.

Two other illustrations by Davis help delineate the narrow parameters within which working women could be portrayed. In an 1881 engraving, she captured a diverse group of women waiting in the anteroom of the Working Woman’s Protective Union (fig. 9). Although the vast majority of the union’s clients labored in the garment industry and as domestic servants, Davis chooses here to show us women who could be typographers, stenographers, and telegraph operators as well as women in manual pursuits. The young woman warming her foot on the stove and especially the woman behind the desk appear to be new “types,” recognizing the fact that by 1870 over one-third of New York City’s workforce was female. While earlier the inability to distinguish between those who worked and those who did not registered as social unease, Davis’s image suggests that some forms of paid work no longer placed women outside the bounds of respectability. The seated female clerk in the right foreground, checking a register for an older woman who waits patiently, acknowledged that benevolent enterprises had emerged as major employers of educated single women and that women created and sustained the institutional infrastructure of charity.

On the other hand, an image Davis made late in her career at Leslie’s demonstrates the persistent anxiety about women in commercial settings. In “Pawning the Wedding-Ring,” Davis centers her narrative on a young woman holding a baby as she hands her ring to a pawnbroker (fig. 10). The image is at once sentimental about marriage and forthright about the continuing economic plight of some women. Although the pawnbroker’s stereotypic physiognomy (and trade) identifies him as Jewish, the central figure evokes a ragged Madonna of the streets, a pictorial convention that often signified the immigrant working poor. The worried mother returns us to an earlier regime of female economic dependence, as her only hope for feeding her child is to pawn the symbol of matrimony. But she does this not as a typical middle-class mother, dependent on her husband’s income. Rather she is a poor immigrant. For middle-class women, the struggle to survive is now revealed by the varieties of respectable working women in the waiting room of the Women’s Protective Union.

Davis explored her own socio-economic status again in a series of illustrated travel accounts. Appearing in nine installments from 1883 to 1885, the accounts follow the familiar path of the Victorian travel narrative. They begin with the departure and attendant customs inspections and then move on to representations of landmarks and “natives.” Traveling in England, Belgium, Holland, and Germany, Davis repeatedly inserts the artist-reporter into scenes of famous “sights” as she recounts her trip. In these sketches from life, she is clearly the author seen drawing the interior of Westminster Abbey (fig. 11). Although the woman artist has her back to us she is in a public, if sacred, space, recording her experience for readers. Unlike her first appearance with the Utes in the 1880 engraving, the working role of the artist is more fully revealed here. In a visit to Warwick Castle, Davis’s active, productive self is made all the more explicit as she shows herself, the artist-reporter, eagerly jotting notes and making quick sketches (fig. 12). Davis’s freedom to represent herself may have been the result of her distance from American shores; it may also express her growing self-confidence as a figure in the world of illustration. The latter is certainly suggested by the range of her creative work. Through the 1880s, while still working as a Frank Leslie’s staff artist, Davis learned to etch and exhibited her work. She also benefited from publishers’ active promotion of their illustrators. It had become clear to publishers that linking their products to particular artists helped sell those products.

The reorganization and professionalization of artistic training in formal institutional settings, and especially the expanding numbers of women crowding into art schools, made the figure of the woman artist at the turn of the century culturally significant and potentially subversive. Much like the “world turned upside down” images of woman suffragists in the 1850s and 1860s, Gilded Age cartoons of women artists warned of the likelihood that their work would render them masculine. Cultural meanings attached to the figure of the woman artist shifted: she did not simply offer a symbol feminists could draw on to dramatize women’s entrance into public spaces and work; she had become a more threatening force, potentially undermining the status of the arts professions in general. In response, male artists, critics, and gallery owners built informal and formal institutions (such as clubs and exhibition venues) that excluded and marginalized women artists, that fostered an image of the professional artist as male, and that equated the highest aesthetic values with men.

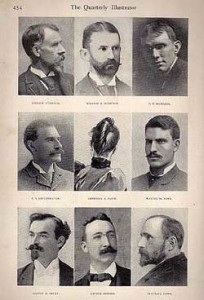

Davis’s only known self-portrait appeared in the Quarterly Illustrator in 1894 and suggests some of the tensions at play as definitions of high and low and feminine and masculine were redrawn. The Quarterly Illustrator, published by Harry C. Jones from 1893 to 1894 in New York City, was an unparalleled venue for anointing illustrators as personalities, even celebrities. In the years before Davis’s portrait was published, she had received significant critical attention. And her growing fame makes it difficult to read her self-presentation in this very public guidebook to American illustration (fig. 13). Her “portrait” stands in stark contrast to the photographs of the mustachioed and bearded male artists who surround her. Sketched rather than photographed, we focus on her hair, the angle of her shoulders, and the light shimmering on her head and her puffed sleeves.

Other portraits of women artists in the same volume are similar to those of the male artists’ partly because they are photographs. But, like Davis’s drawing, they also emphasize feminine details of hair, jewelry, and clothing. Although male artists are frequently shown in their workplace, the studio, or holding brushes and palettes, the tools of their trade, few women artists are so portrayed. In this context, Davis’s self-representation is more than idiosyncratic, more than an expression of individual desire to foster mystery or preserve anonymity. As a drawing, her self-portrait draws attention to her skills as an artist. At the same time, the composition lends the portrait a certain ambiguity. Thoroughly fashionable and feminine, the sitter cannot be masculinized—but is she working, is she professional?

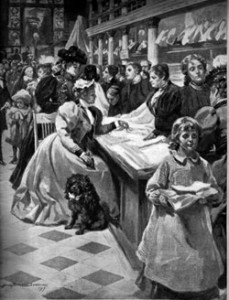

Davis’s self-portrait demonstrates the difficulties of inscribing middle-class women’s work into the visual record. Negotiating between the prostitute, the seamstress, the suffragist, and the domestic angel proved wearing, unprofitable, and perhaps impossible. By the end of the nineteenth century, popular depictions of working women rarely included middle-class women. Instead, they showed women whose physiognomies might have defined them as respectable but whose work could never define them in that way. Alice Barber Stephens, like Davis a pioneering woman illustrator, created a cover for the Ladies Home Journal as part of the magazine’s series on “The American Woman.” Her only image of women at work, “The Woman in Business,” published in 1897, clearly identifies the woman in business as subordinate to the woman who consumes (fig. 14). Standing caged behind the store counter, this archetypal working woman presents fabric to her customer—a seated, fashionable woman, shopping with her dog.

Davis’s self-image, made at a moment when her distinctive signature was well known, captures the paradox of representing middle-class women as workers. Her portrait appeared as pictures of young, white women at leisure drawn by male illustrators became popular icons of American womanhood. By the first decades of the twentieth century, portrayals of the leisure-loving Gibson Girl, Fisher Girl, or Christy Girl had come to dominate the popular press. It was these bicycling, swimming, golfing, and flirting middle-class women who filled the pages of the new mass circulation magazines. These “new women” served as emblems of pleasure and consumption, reinforcing the belief that middle-class white women were simply the beneficiaries of middle-class male achievement.

Further Reading:

Kathleen D. McCarthy, Women’s Culture: American Philanthropy and Art, 1830-1930 (Chicago, 1991) and Nina de Angeli Walls, Art, Industry and Women’s Education in Philadelphia (Westport, Conn., 2001) offer detailed accounts of the American design-school movement. Diana Korzenik’s Drawn to Art: A Nineteenth-Century American Dream (Hanover, N.H., 1985) alerts us to the popularity and outreach of American art education in the period, suggesting how hundreds of rural girls found their way into design schools. Several recent exhibition catalogues provide useful biographical sketches of individual illustrators, designers, and engravers and further develop the story of women who pioneered in these professions. These include: Helena Wright’s, With Pen & Graver: Women Graphic Artists before 1900 (Washington, D.C., 1995); Judy Larson’s introduction to Enchanted Images: American Children’s Illustration, 1850-1920 (Santa Barbara, Calif., 1981); and Phyllis Peet’s American Women of the Etching Revival (Atlanta, 1988). Alice Kessler-Harris’s study of women wage earners Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (New York, 1982) provides the best overall summary of the issues confronting women workers throughout the nineteenth century. For more on white middle-class women’s movement into paid work, Angel Kwolek-Folland, Engendering Business: Men and Women in the Corporate Office, 1870-1930 (Baltimore, 1994); Mary P. Ryan, In the Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family In Oneida County, New York, 1790-1865 (New York, 1984); Cindy S. Aron, Ladies and Gentleman of the Civil Service: Middle Workers in Victorian America (New York, 1987); and Ava Baron, ed., Work Engendered: Toward a New History of American Labor (Ithaca, N.Y., 1990). In Difficult Subjects: Working Women and Visual Culture, Britain 1880-1914 (London, 2002), Kristina Huneault explores the representation of working-class women in advertising, popular culture, painting, and photography. To explore the impact of Leslie’s publications and understand its readership, consult Joshua Brown, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley, 2002). Michelle Bogart considers the cultural location of illustrators and illustration in the Gilded Age as the lines between popular and high art hardened in Artists, Advertising and the Borders of Art (Chicago, 1985). Two recent studies debate women artists’ attitudes toward professionalization and their training: Kirsten Swinth, Painting Profesionals: Women, Art and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870-1930 (Chapel Hill, 2001), and Laura Prieto, At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); while Sarah Burns’s Inventing the Modern Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America (New Haven, 1996) considers the shifting cultural significance of artists and illustrators and their modes of self representation in the period. Carolyn Kitch surveys the emergence of the American girl in popular periodicals in The Girl on the Magazine Cover: The Origins of Visual Stereotypes in American Mass Media (Chapel Hill, 2001) and Off the Pedestal: New Women in the Art of Homer, Chase and Sargent (New Brunswick, Conn., 2006) traces her emergence in American painting.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Barbara J. Balliet teaches women’s and gender studies at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. She is completing a book on the work and lives of women engravers and illustrators in the second half of the nineteenth century.