Sponsored by the Chipstone Foundation

Introduction

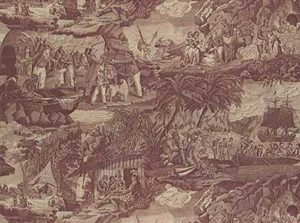

Today a gallery of the Nantes History Museum’s Château des Ducs de Bretagne relates information about the transatlantic slave trade. Within stands a lit à la Duchesse, whose faded but once stylish toile ensemble reveals striking antislavery graphics (figs. 1, 2). One scene bears the title “Traite des Nègres”—Slave Trade—on a wooden sign printed in repeat across the fabric.

Toile, short for toile de Jouy (after the Oberkampf factory in Jouy-en-Josas, France), is cotton, linen, or silk printed with monochromatic scenes, often dyed in red, blue, or black. The word “toile,” meaning cloth, derives from the Latin root tela, or web—an apt metaphor for the network of painters, engravers, and printmakers linked through Traite des Nègres. For example, while signed “E. Feldtrappe,” Traite’s scenery reflects contributions by six French and British artists inspired by the cause of abolition. Feldtrappe’s cloth (circa 1825) re-disseminated imagery from late eighteenth-century abolitionist prints, underscoring their currency well into the nineteenth century as slavery persisted.

Seemingly deemphasized by their use for decorative upholstery patterns, Traite‘s vignettes, in fact, would have been difficult to miss, especially when draping windows or objects of repose, and hence viewed at close range. While private today, bedrooms were semi-public spaces for centuries, and bed draperies were among the most expensive and prestigious household possessions. Politically commemorative toiles were au courant material for entertainment and stimulating discussion within the personal yet open setting of the nineteenth-century bedchamber or parlor. Traite was printed to promote abolition, despite its inevitable use in households made wealthy by the trafficking it denounced.

This article will discuss how Traite des Nègres came to be produced, and will consider its use, meaning, and relationship to antislavery activity and related artworks. As will be shown, the cloth’s scenes blend French, British, and American abolitionist expressions, characterized by Enlightenment ideals, romantic themes, and moralizing sentiment. Made near Rouen, part of France’s commercial slave-trading center, Traite is a symbol of the Atlantic world in which slaves labored over and were physically bartered for cotton. Further, it is a material fragment of a vast global cloth trade—identified by Giorgio Riello as the effect of a progressive shift in the textile-manufacturing core from Asia to Europe, spurred by industrialization in France and Britain.

Made near Rouen, part of France’s commercial slave-trading center, Traite is a symbol of the Atlantic world in which slaves labored over and were physically bartered for cotton.

Traite, together with its sources, represents the interrelationship of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century textile and slave trades with colonial racial identity and experience in Europe, Africa, and America. While its use is yet undocumented in North America, surviving mulberry-on-white lengths have been collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, with a saffron-colored remnant at the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum. Other samples exist in at least seven other collections outside the United States, confirming the cloth’s popularity and the quantity of its manufacture. While the only known “furniture cotton” devoted to abolition motifs, Traite des Nègres is akin to other historic toiles celebrating liberty, some manufactured for a post-Revolutionary American market. For example, L’Hommage de l’Amerique à la France (“America’s homage to France,” produced by Oberkampf around 1780) includes a kneeling slave holding up a leaflet before an allegorical figure of France.

Traite des Nègres

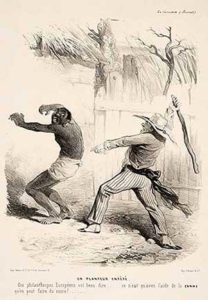

Read clockwise, Traite‘s four interlocking scenes begin in an Edenic Africa before the arrival of trade-seeking Europeans. Kind-hearted Africans rescue shipwrecked voyagers from drowning. Yet in the final scene, the welcomed Europeans (and a complicit African) have been transformed into brutal slave traders, one with a bludgeon and another with a branding iron at his feet. A native man is torn from his family, and another sits shackled in a rowboat. The menacing slave trader—an unlikely subject for bed linens—is included in other abolition-inspired stories and images. A figure with upraised baton is seen in Samuel Wood’s 1805 broadside Injured Humanity, and in Charles-Émile Jacque’s Un planteur entêté (An obstinate planter), ca. 1830, from La Caricature, a Parisian satirical magazine (figs. 3, 4). L’Histoire de Paul et Virginie, the iconic novel of 1788 by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint Pierre set on the island of Mauritius, describes a confrontation with a cruel slave master. This scene was reproduced on fashionable Paul et Virginie toiles, including one designed by Favre, Petitpierre et Cie of Nantes, ca. 1795. But how did the printing of such scenery on furnishing fabrics come about?

The seventeenth-century “calico craze” for brightly colored, painted, and printed Indian cottons, exported mainly via the British East India Company, led to competitive embargoes in France. Resulting import substitution practices were also banned until 1759. An indienne (meaning “Indian”) was a French fabric designed in emulation of the restricted fabrics. They were known also as toiles peints, or “painted cottons.” Though prohibited, l’indiennage continued apace in Marseilles, Rouen, Nantes, and elsewhere in France.

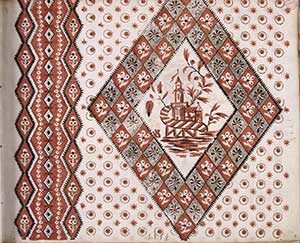

Inspired by les indiennes, toiles were often printed with historic, literary, or commemorative subjects, such as Le Ballon de Gonesse (1784, Oberkampf), celebrating the invention of the hot air balloon. Superseding the block-printing of indiennes, toile production utilized a new copper-plate method that—together with innovations in the use of mordants (used in dyeing to fix the coloring agent), cloth weaving, and finishing—led to rapid production and revolutionized the European export trade. In La Toile Imprimée et Les Indiennes de Traite, Vol. I (1942), collector and historian Henry-René d’Allemagne illustrates Traite des Nègres amid his indiennes decorated with abstract pattern work and some African figures. Thousands of indiennes de traite of the sort catalogued by d’Allemagne were originally made in and exported from French slave-trading cities (including Nantes and Bordeaux) as currency in exchange for African merchandise and slaves, who were sent to labor in the French colonies (fig. 5). (Cottons, including indiennes that were made for the African market, were termed “Guinea cloths,” along with competing fabrics woven in West Africa.) At the same time that indiennes were traded for slaves, Traite des Nègres commemorated the slaves’ plight and demanded their freedom. Like the smiling mascarons of Africans on Nantes building façades, Traite reflects moral ambiguities that were perhaps conveniently ignored in Normandy, where it was manufactured.

As Christopher L. Miller explains, while “[t]he products and profits from the labors of enslaved Africans returned to France, Africans themselves did not.” Slavery was officially banned in France in 1794 (although Napoleon restored its legal status in the French colonies in 1802, where it was deemed a necessity), and it was, as Miller states, “[a] risky proposition to bring a slave to France; consequently, few Africans ever saw the metropole that controlled the Atlantic triangle.” Although abolitionist societies were formed in France, and antislavery tracts and novels such as Victor Hugo’s Bug-Jargal (1826) and George Sand’s Indiana (1832) circulated widely, at the time Traite des Nègres was made, there had been only limited efforts to curtail the French slave trade and colonial reliance upon slave labor. As Lawrence C. Jennings has shown, French abolitionism in the 1820s and 1830s emanated from a small literary and parliamentary elite, was generally disorganized, and generated little public support. Though government authorities paid lip service to attempts to eradicate the slave trade after 1815, its elimination was seen by many in France as a British maneuver to weaken the French colonies.

However, French antislave trade rhetoric, suppressed under Napoleonic rule and limited under the Restoration and July Monarchy, was encouraged from afar by British abolitionists, and in France by the La Comité de la Société de la morale chrétienne pour l’Abolition de la Traite des Noirs (founded 1821) and Société Française pour l’Abolition de l’Esclavage (founded 1834). Philosophes such as the Marquis de Condorcet of La Société des Amis des Noirs publicly denounced African slavery. Those groups’ activities, along with the published exposé Faits Relatifs a la Traite des Noirs [Facts Relating to the Slave Trade] (1824) and the repeated passage of laws aimed at reining in the trade, fanned the sorts of abolitionist sentiments reflected in the manufacture of this provocative fabric, perhaps commissioned by one of the aforementioned groups.

A substantial market for Traite des Nègres existed in Britain, if not in France, and it was likely made for export there, where most surviving examples have surfaced in recent decades. As David Brion Davis and Peter P. Hinks have shown, England, second only to Portugal as the Atlantic’s leading slave trade nation, rapidly re-positioned itself as slavery’s most outspoken critic amidst American, French, and Haitian revolutionary activity. This action was inspired, in part, by the rise of reform sentiment led by the American Quaker Anthony Benezet, who helped form the Atlantic’s first antislavery society in 1775.

Another decisive moment for antislavery forces in England and America was the formation in London in 1787 of the Quaker-led Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The Society’s famous emblem, a manacled slave kneeling beneath the words, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother,” was modeled by William Hackwood and sold by Josiah Wedgwood as a jasperware cameo (fig. 6). The abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote: “Of the ladies, several wore [the Wedgwood medallions] in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and thus fashion … was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.” The movement’s growing reach is further indicated by the appearance of a pair of mezzotints by prolific London printmaker John Raphael Smith. Smith’s Slave Trade and African Hospitality were published in February 1791 after canvases by the English painter George Morland (figs. 7, 8). Several decades later, Traite des Nègres was manufactured bearing the signature of textile engraver Frédéric Etienne Joseph Feldtrappe, reproducing Smith’s prints after Morland as well as two other French antislavery scenes.

Frédéric Etienne Joseph Feldtrappe

Born in Saint-Just-les-Marais (Oise) on July 8, 1786, Feldtrappe was the son of Marie-Thérèse Lafond and Frédéric Gottlieb Feldtrappe, a Dresden-born engraver and designer of indiennes. As textile historian Xavier Petitcol has shown, Feldtrappe spent his career in Normandy, specifically the towns of Beauvais, Canteleu, and Déville-lès-Rouen, thus in proximity to the French ports that sent out slave ships, especially Rouen. Documents discovered by Serge Chassage indicate that Feldtrappe worked at Canteleu between 1821 and 1823 and then at the Girard manufactory in Déville-lès-Rouen by 1830. It is possible that Traite was designed in one of those locales. Since French indiennes were a regular export to the African market, it seems possible that Feldtrappe’s concept for Traite was influenced by his knowledge of this textile trade with West Africa, of which Rouen was a particular center, as Ann DuPont has shown.

On January 31, 1816, the younger Feldtrappe married Marie-Victoire Droz in Beauvais. Charles Thomas Feldtrappe, their son, is also recorded to have been an engraver of indiennes in Suresnes (near Paris), indicating that several generations of the family pursued the same profession. It is possible that they operated their own textile manufactory, but no records have been found to that effect. Etienne Feldtrappe died in Suresnes on October 8, 1849.

Xavier Petitcol has identified seven varieties of Feldtrappe’s toiles, most of which are signed. He seems to have exclusively produced this lightweight, easily laundered fancy cloth, usually used in the summer to transform a bed alcove or other interior by way of eye-catching and amusing scenery. Beverly Lemire has shown that Indian printed cottons were used initially in Europe for upholstery, not clothing, and that their use as bed hangings, tablecloths, or valances stemmed from the “architectural” ways that travelers saw them being used in India. The use of toile draperies followed suit, with swathed beds forming tent-like spaces.

Feldtrappe would have carried out the process of engraving his designs, along with various other steps, in a specialized workshop housed in a textile manufactory. Traite’s repeating pattern, consisting of two registers with dual scenes in each, was achieved using a large engraved copper-roller printing machine of the type invented by Thomas Bell in 1783 and introduced in France in 1797. The roller printer mechanism involved a copper roller that turned against a large cast-iron roller wrapped in lapping, a cushioned material. A rubber-covered feeder roller turned in a tray filled with dye below the copper roller, supplying the color that the engraved roller would apply to the fabric.

The “Slave Trade,” “African Hospitality,” and the Morland Gallery

Feldtrappe selected four prints to arrange into Traite’s visual narrative that he then engraved onto the copper roller. These included two that were faithfully engraved by John Raphael Smith after Morland, who composed The Slave Trade (originally titled Execrable Human Traffick or The Affectionate Slaves), which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1788. With this canvas, Morland made a break from the trendy genre pictures of country life for which he was known—such as Milk Maid & Cow Herd, Cottage Family, and Enamor’d Sportsmen. (A satirical cartoon by James Gillray, Connoisseurs examining a collection of George Morland’s [1807] pokes fun at these pictures and their collectors, though they were widely appreciated.)

The specific impetus for The Slave Trade painting might well have been an abolitionist poem. In his 1805 biography of Morland, the writer William Collins claimed that his own 1788 verse “The Slave Trade” inspired the canvas, though the opposite also is possible. Portraying an African chief separated from his wife Ulkna and son Tengarr, Collins wrote, “With hands uplifted, he with sighs besought/ The wretch that held a bludgeon o’er his head,/ And those who dragg’d him, would have pity taught/ By his dumb signs, to strike him instant dead.” Similarly, Morland’s painting shows an African being separated from his family as he is physically threatened. Several scholars, including Ellen G. D’Oench, have noted that Morland’s image also refers to Wedgwood’s enchained slave.

The Slave Trade undoubtedly generated interest, because Morland quickly painted a related picture—African Hospitality, which was exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1790. It depicts the rescue of shipwrecked Europeans amidst a storm. At the center, an African woman with an infant bundled on her back helps up a nearly drowned traveler as lightning flashes in the background. When Morland’s second canvas was exhibited, a proof of Smith’s mezzotint, African Hospitality, was hung alongside it. Smith offered his prints in pairs or sets, and thus may have encouraged Morland to produce African Hospitality to pair with The Slave Trade. (D’Oench suggests that John Raphael Smith worked with Morland to produce African Hospitality thereby “alleviating the transgressive theme of The Slave Trade” with the second canvas’s redemptive one.)

Although Collins asserts that the source was again his own poem, it is possible that African Hospitality was inspired by reports of the kind treatment the survivors of the wreck of the Grosvenor East Indiaman received from Africans near Cape Province, South Africa, in August 1782. Smith’s mezzotint includes verses below that emphasize the Africans’ heroism: “Dauntless they plunge amidst the vengeful waves and snatch from death the lovely sinking fair. Their friendly efforts lo! Each Briton saves! Perhaps their future tyrants, now they spare.” Smith issued his next Morland-inspired mezzotint, Slave Trade, in 1791 (fig. 9). A similar inscription at the bottom reads: “Lo! The poor Captive with distraction wild/ Views his dear Partner torn from his embrace./ A different Captain buys his Wife and Child-/ What time can from his Soul such ills erase?” While Morland’s pictures have been linked with Collins’ stanzas, the source of all of Smith’s verses is unrecorded.

During the period of the Napoleonic wars, British interest in narrative genre subjects diminished, as subjects including military heroes, modern history themes, and topical caricatures by Gillray and others proliferated. Moreover, British access to Continental markets declined. D’Oench cites a contemporary commentator’s lament that “in one print shop alone … there is stock in trade to the amount of fifty thousand pounds sterling now lying dead in their drawers which stock would, if the country had not been accursed by the war, have been certainly circulating, and probably sold on the Continent.” In order to promote sales, Smith created a “Morland Gallery” of about sixty of Morland’s original paintings, which he offered for sale with the engravings after them. With Slave Trade and African Hospitality, his choice of subject matter was especially timely.

La Citoyenne Rollet

Although the original painted source of two of Feldtrappe’s scenes is English, it is likely that all four print sources were French. For example, a 1794 stipple engraving Traite des Nègres was printed by François-Jules-Gabriel Depeuille, a publisher on the rue St. Denis in Paris. Depeuille offered numerous prints promoting French Republican ideals, including Louis Darcis’ engravings of sculptures by Louis-Simon Boizot such as La Liberté and Moi Libre aussi. While Morland is identified as the original source of Depeuille’s print, the engraver is the obscure “la citoyenne [citizeness] Rollet,” whose name appears at the lower right of the engraving. Rollet’s Traite des Nègres is fully described in the Parisian Gazette Nationale of March 12, 1794 and advertised for six livres in black and white, twelve in color. While it is probable that Rollet copied Smith’s “Slave Trade” print rather than having worked directly from a version of the Morland painting, she made prints after four of Morland’s canvases that were not, so far as is known, reproduced by Smith, including A Tea-garden and St. James’s Park. Rollet’s Traite, like Morland’s and Smith’s, did not include a coal pot with branding iron, which was Feldtrappe’s addition to the scene.

Few traces of Citizeness Rollet remain. She is identified in Jules Renouvier’s Histoire de l’art pendant la revolution, 1789-1804 (1863) as the maker of La Fraternité after Boizot, a portrait of Jean-Paul Marat, and Traite des Nègres. According to Bénézit: Dictionnaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, a Madame Rollet was the wife of Louis René Lucien Rollet, though it further explains, “There was also a young woman using the name Rollet who, around 1800, made stipples from drawings.” According to Xavier Petitcol’s catalogue of Norman toile engravers, a Marius Rollet was born in 1796 in Rouen into a family of dessinateurs-graveurs, including his father Louis Boniface Rollet, an indienne designer. While no relationship is proven, the appearance of Citizeness Rollet’s prints on Traite des Nègres suggests a possible connection between the Rollets and Feldtrappe.

Rollet was included in a 1901 exhibition at New York’s Grolier Club, which showed her image of a West Indian mother and child, titled Toi enfin sera heureux—“You will be happy at last.” It is described in the catalogue as “a print on the emancipation of the negroes by the Revolution” and was also distributed by Depeuille in 1794.

The inscription accompanying Rollet’s Traite des Nègres refers to the National Convention’s abolition of slavery in the French colonies on “le sixième Pluviose” (February 4, 1794), and states: Quel contrat infame, l’un Marchande/ Ce qui n’appartient à Personne/ L’autre vend la Propriété/ De la Nature./ Ce vil métier a été aboli par la Convention Nationale le 16 Pluviose l’An deuxième de la République française une et indivisible. (What infamous contract, one that barters over what belongs to nobody, the other that sells ownership over nature; this vile practice was abolished by the National Convention, February 4, 1794 of the second year of the singular and indivisible French Republic.) Other than the difference in verses, Rollet’s engraving does not vary in composition from Morland’s or Smith’s.

Rollet’s own L’Africain Hospitalier—also after either Morland or Smith—bears an inscription quoted from a stirring patriotic speech made by a “un homme de couleur” (man of color) at the same meeting of the National Convention referred to above (fig. 10). Though the speaker’s name is not recorded, this speech was probably made by one of three delegates from Saint Domingue. Rollet’s engravings celebrate the 1794 National Convention, whose emancipatory proclamations had short-lived effect; Napoleon reestablished slavery in 1802, and France subsequently meandered toward its final abolition in 1848. With France’s sale of its Louisiana territory in 1803, antislavery efforts in America were also derailed as slavery became re-entrenched when cotton took off as the country’s primary export.

Nicolas Colibert, Pierre Thomas Victor Fréret, and “Le Mythe du Bon Noir”

Though historian and textile collector Henry-René d’Allemagne documented Etienne Feldtrappe’s adaptation of Morland’s paintings from Smith’s prints in 1942, the origin of the other two scenes has until this point remained unidentified. I discovered that Feldtrappe borrowed from two additional prints: Habitation des Nègres and Arrivée des Européens en Afrique, both produced by Parisian engraver Nicolas Colibert in 1795 (figs. 11, 12). A series of Colibert’s four prints, held in the collection of the John Carter Brown Library, includes Habitation des Nègres, Arrivée des Européens en Afrique, Le Culte des Nègres, and Le Mariage des Nègres, all produced in 1795 after paintings and drawings by Fréret, as noted by Colibert’s inscription “Fréret pinxt.” Colibert’s prints, like the thematically related engravings by La Citoyenne Rollet, were published by Depeuille.

Colibert’s exotic portrayals of African life have been variously attributed to “Louis Fréret” or “Amédée Fréret” in the notes of collections that include the Colibert prints, though none of the attributions are substantiated, and none of the original paintings have been located. French ethnologist Ernest Théodore Hamy reported in 1898 that “Pierre Fréret” of Cherbourg is the author of the original tableau, Mariage des Nègres, and loosely connects him with La Société des Amis des Noirs. Born in 1714, Pierre Fréret was a founder of the La Société académique de Cherbourg, and fathered a family of artists that included sons Pierre Thomas Victor Fréret, a marine painter, Louis-Barthelemey Fréret, who created botanical prints at Versailles, and François-Armand Fréret, a sculptor.

In “Une dynastie d’artistes: les Fréret” (1990), Jean Fouace identifies Pierre Thomas Fréret with the Colibert prints, along with illustrations for Bernardin de Saint Pierre’s L’Historie de Paul et Virginie. (The novel, performed as a comic opera in London in 1800, was translated into English by Helen Maria Williams, herself associated with Amis des Noirs.) Yet, Pierre Thomas Fréret has not been linked with Amis des Noirs, nor do prints associated with Fréret and Paul et Virginie appear to exist. It is probable that the Colibert prints are those to which Fréret descendants later referred, and that Pierre Thomas Fréret produced the missing artworks on which they are based. In the 2000 exhibition catalogue Regards sur les Antilles, Fréret’s series is identified as Le Mythe du Bon Noir (The Story of the Benevolent Black), though it is not clear whether this was its original, given title.

The direct inspiration for Fréret’s imagery is uncertain, and the Fréret-Colibert series makes no reference to a specific locale or nation. It begins with Habitation des Nègres, the source for Feldtrappe’s first scene showing Africans in a tropical paradise as a trading ship approaches in the distance. As with each print in the series, abolition-inspired verses like Smith’s accompany Habitation, locating the picture within the sphere of Romantic literature condemning slavery. Colibert’s reproductions and accompanying verses call to mind historic binary perceptions of Africans as either innately noble and pure or as savages whose lack of cultivation called their very humanity into question.

The following poetry, whose author is identified only as “Person,” decries slavery as a product of the “civilized” world and a crime against nature.

Tranquille dans sa caze au sein de son ménage,

Qu’il est intéressant ce bon couple africain,

Qu’un préjugé barbare à fait nommer sauvage.

Sauvage! Un peuple doux, industrieux, humain.

Et fait, en inculcant en lui nos connaissances,

Pour professer nos arts et nos hautes sciences.

Mais l’abolition de la traite homicide,

Que la cupidité fit sortir des enfers,

Et que l’humanité vient dans son vol rapide

Détruire pour jamais en brisant tous ses fers;

Va rendre libre enfin, au nom de la nature,

Ce nègre infortuné qu’abrutit la torture.

Happy in their home with family,

How curious it is that a prejudiced

barbarian has labeled this good African couple as savage.

Savage! A gentle, industrious, human people.

And so, we impose our knowledge on them

To teach our great arts and sciences.

But the abolition of the homicidal trade,

That [our] greed unleashed from hell,

And humanity will come in quickly to

Destroy it for all time by breaking its chains;

Will at last, in the name of nature, free

This unfortunate black reduced by torture.

These verses, while not incorporated onto Feldtrappe’s cloth, still illuminate the context for the Fréret-Colibert pictures as they relate to French abolition. Analogous to the Morland-Smith pictures and verses, the Fréret-Colibert illustrations, with their references to man and nature, convey romantic sensibilities in contrast with other prosaic antislavery writings and utilitarian artifacts.

Colibert’s second print, Arrivée des Européens en Afrique and the basis for the second of Feldtrappe’s scenes (reading clockwise), shows foreigners welcomed by Africans who seem eager to engage in friendly commerce. One man—already in possession of an imported blue headscarf—holds ivory tusks that he is prepared to barter. A nearby basket is filled with ostrich eggshells, which often were decorated and sold. The accompanying verses emphasize the baseness of “greedy European” brutalities in light of friendly trade with the “gentle African” portrayed:

Pour la première fois, quand le doux africain

Reçut, à bras ouverts l’avide européen,

Il ne se doutait pas qu’un jour avec furie,

On viendrait l’arracher de sa caze chérie.

Si de ce sol brûlant, nous nous fumes encore

Contenté d’emporter, les peaux, l’ivoire et l’or!

La tendre humanité n’aurait point à se plaindre

Des forfaits inouis qu’on frémirait de peindre.

When the gentle African first welcomed

The greedy European with open arms,

He already knew that one day he would be

Ripped out and dragged from his beloved home.

If, from this scorched earth, we were so

Happy to take the skins, the ivory, and the gold!

Our fragile humanity should not complain about

The inconceivable brutality of these crimes.

Colibert, who spent some years in London, may have taken his cue for this print from Morland and Smith’s African Hospitality.

The Fréret-Colibert series includes two more images that were not incorporated by Feldtrappe: Le Mariage des Nègres and Le Culte des Nègres. Omitting them, Feldtrappe inserted Morland’s images in their place to achieve his own narrative culminating in a dramatic slave capture. Yet, Colibert’s Le Mariage, a slave wedding full of dancing and joy, and Le Culte, glorifying African life by capturing the Africans’ reverence for nature, relate the same message: The African is inherently good and honorable and “guided by reason,” in contrast with the “brutal occupier.”

Pour le fiers Citadins, admirable leçon!

Humanité, tendresse et constance et courage…

Voilà l’homme, pourtant, qui né dans l’esclavage,

Nourit de ses sueurs, le sévère Colon

Fidèle dans son culte, ami de la raison,

Jusque dans ses amours il respecte l’usage:

Sous les loix de l’hymen, l’honneur fixe les voeux

D’un couple ardent, que lie une foi mutuele:

Ce beau jour est la fête et des ris et des jeux,

Le tableau du bonheur, cent fois, s’y renouvele;

Et les époux qu’enivre une franche gaîté,

Perdent le souvenir de leurs captivité.

What a wonderful lesson for our proud citizens!

Humanity, love, perseverance and courage…

Here is man, being born into slavery,

Working hard to feed the brutal occupier

True to his rituals, guided by reason,

Even in love he adheres to his customs:

Under the law of marriage, honor binds the

Wishes of a passionate couple united in faith:

This is a day of celebration, pleasure and games,

A picture of joy one hundred times renewed,

The spouses exhilarated by true happiness

Forgetting about their captivity.

Le Mariage and Le Culte capture the impulse to undercut anti-black feeling by representing Africans as naturally sympathetic, courageous, and in harmony with God and the natural world, while white slave-traders are described as irreverent “unbelievers.” Le Culte‘s accompanying verses describe a cathedral of nature, where Africans display their devotion to the supreme being:

Un gâson est l’autel, un creux d’arbre est le Temple

Ou, dans un peu de terre, un vieux trone, un serpent,

L’habitant de ces lieux entrevoit, et contemple

La majesté du Dieu qui règne au firmament,

A la Lune, sur tous, le Nègre rend hommage,

Il pleure son absence, il chérit son aspect,

Et de l’être Eternel dons il cherche l’image,

La grandeur est partout l’objet de son respect

De cet être avec nous, confessés l’existence,

Incrédules humains par l’orgueil égaré;

Quand le Sauvage même adore sa puissance,

Tombés devant le dieu par qui vous respirés.

Tree branches form an altar, a hollow tree is the temple

And in a little dirt an old throne, a snake,

The native people glimpse at and contemplate

The greatness of God who reigns in the firmament,

The black prays above all to the moon,

He laments its absence and adores its appearance,

And he deeply honors the greatness of the

Eternal being whose image he seeks to find.

To this God we confess our lives,

We, the unbelievers due to misguided pride;

While the savage admires His power,

Humble in admiration before the God he reveres.

Generally, Colibert’s pictures and their impassioned proclamations take the form of a racialized counter-caricature of black persons as ideal children of nature, and relate to what Hugh Thomas describes as abolitionists Benjamin Constant and Germaine de Staël’s “cult of ‘le bon negre.'”

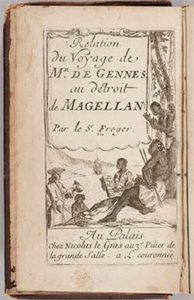

Colibert’s Habitation and Arrivée may be compared to the frontispiece illustration of François Froger’s travel account, A relation of a voyage made in the years 1695, 1696, 1697, on the coasts of Africa, Straits of Magellan, Brasil, Cayenna, and the Antilles, by a squadron of French men of war, under the command of M. de Gennes, published in Paris in 1700 (fig. 13). This illustration of trade on the African coast in the late seventeenth century shows a reclining but armed Alcaty, an African “governour” encountered by M. de Gennes and Froger. Colibert shows similar reclining figures in his coastal scenes. The frontispiece and several related plates incorporate aspects of Froger’s tales, including De Gennes exchanging a bottle of brandy (and other trade goods, including cutlery and paper) with Alcaty for barrels of fresh water. An African man in the middle ground wears a tunic of checkered cloth and holds a bolt of the same; he (or Alcaty) reappears in subsequent plates wearing the same dress, emphasizing the popularity of the cloth on the African coast (fig. 14). Froger’s frontispiece, suggesting how central the cloth trade was in Africa, is echoed in the Fréret-Colibert Habitation and Arrivée prints—and ultimately on Feldtrappe’s antislavery fabric, effecting a unity among these pictures that is more than coincidental.

Ernest T. Hamy links Colibert’s prints with those of the Roman-born painter Agostino Brunias, who studied with Robert Adam and spent much of his career in London and in the West Indies. Brunias’ A Family of Charaibes in the Island of St. Vincent, executed for Sir William Young in the early 1770s and showing Indian women and children gathered in front of rudimentary huts, is similar to Colibert’s Habitation; neither is intended as ethnographic study, but rather as picturesque and semi-erotic scenery. Along with the indiennes traded for Africans and the abolitionist narrative of Traite des Nègres, Brunias’ paintings link an international cloth trade with historic patterns of racial identity. On the island of Dominica, Brunias found in the ethnic variety of the populace a rich subject matter for his paintings, and he emphatically addresses the Caribbean textile trade in a series of paintings, including Linen Day, Roseau, Dominica, A Market Scene (ca. 1780), whose focal point is a wealthy Creole (or French or English-born) woman selecting cloth at a local market. Her all-white dress stands in contrast to the striped and madras garments worn by the mixed-race community bustling around her. In A Linen Market with a Linen-stall and Vegetable Seller in the West Indies, ca. 1780 (and on at least one other canvas), Brunias repeats the familiar market scene, replacing the Caucasian woman with a well-to-do “mulatress,” wearing the same white gown, yet about whose shoulders appears a striped fichu (fig. 15). Again, similar clothing is the predominant motif of several Brunias canvases featuring “handkerchief dances,” which also feature contrasting white and striped fabrics that visually underscore the blended quality of the society depicted (fig. 16).

Fréret and Colibert were not so much followers of Brunias (as Hamy indicates) as adherents to a long-standing tradition of fanciful and idealized treatments of colonial geography. For example, the romantic trope of the exotic bon sauvage (“noble savage”) existing untainted by society’s corrupting influence enjoyed popularity in late eighteenth-century art, especially as it pertained to the French Revolution. Yet it had roots in an older tradition. Such images hearken back to portraits of Indians in Theodor de Bry’s well-known sixteenth-century illustrations of Spanish conquest in the Americas and John White’s Roanoke Island watercolors.

While Froger mentions in his travel account that he traded “Linen-Cloth” and “printed Calico’s,” the checkered fabric illustrated in his book is of ambiguous origin. For example, textile and slave centers like Rouen exported Guinea cloths of striped and checked patterns to Africa, yet African-made cottons with similar patterns competed locally against such overseas commodities. In The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric (2001) Michel Pastoureau reflects on the historic association of striped fabrics with transgression, citing medieval European sumptuary laws requiring hangmen and prostitutes to wear them. While such associations may have been long forgotten, the checked Guinea cloth and Brunias’ striped weaves in Dominica nevertheless call to mind the rupture of social or moral order that slavery (and miscegenation) represented to abolitionists—because slaves often wore and were traded for those fabrics. Conversely, Feldtrappe’s Traite des Nègres was a luxurious decorating fabric whose ostensible purpose was to promote the restoration of slaves to their natural state of freedom. A self-referential critique of slavery, Traite also shares a history with les indiennes des traite (i.e., cloth traded in Africa and the Americas) that is the source of its symbolic efficacy.

A Fashion for Abolition

While Traite des Nègres was inspired by abolitionism, such toile is unlikely to have been manufactured unless deemed salable, its profitability estimated by the sustained popularity of the prints on which it was based. Like Traite des Nègres, handkerchiefs, wallpapers, and a plethora of other objects were printed with decorative antislavery patterns, especially in nineteenth-century England and America. While the dispersal of these objects commercialized and commodified the movement’s principles, it promulgated antislavery messages among a wide audience and raised money to promote them, as well.

For example, the United States’ Fugitive Slave Act (part of the Compromise of 1850), which made it illegal to harbor runaway slaves, inspired the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), originally serialized in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era. Uncle Tom-related objects include a handkerchief titled “Little Eva’s Song (Uncle Tom’s Guardian Angel)” accompanying musical notes and lyrics published by John P. Jewett & Co. in 1852. Recently, the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Conn., acquired an English-made “Uncle Tom” wallpaper fragment manufactured in 1853.

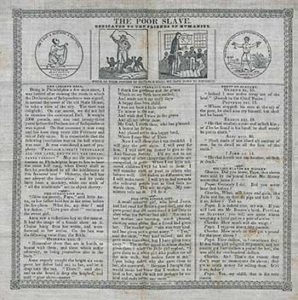

“Newspaper-style” printed handkerchiefs promoted the abolitionist cause, especially among children. “The Poor Slave (Dedicated to the Friends of Humanity)” printed by the Boston Chemical Printing Company around 1835 is a handkerchief bearing the Wedgwood emblem and a slave trader with a whip. On its printed surface, a passage titled “The Thankful Girl” recounts the resolve of a virtuous child: “I will save my money to give to the Anti-Slavery Society. I’ll try not to eat any sugar or other things that the slaves are compelled to grow” (fig. 17). Abolitionists in England and America, including the American Free Produce Society, boycotted sugar, rum, and slave-grown cotton. Between 1803 and 1937, cotton was North America’s greatest export, and supplied the British and French textile mills that manufactured cloth like Traite des Nègres. Therefore, the very existence of these abolitionist textiles is directly traceable to slave labor. With the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, the efforts of French, English, and American abolitionists whose ideals were promoted via the objects discussed here finally came to fruition with the eradication of slavery in the United States.

Conclusion

Beyond the handiwork of the six individual artisans that was incorporated into Traite des Nègres, the cloth reflects a gamut of French and British ideas about slavery and race, imbued with a sense of romantic idealism and revolutionary rhetoric, and influenced by early New England antislavery campaigns. A history of Traite’s production reflects the nineteenth-century transatlantic world’s greater economic mechanism—simultaneously underwritten and undermined by contrary views of the agricultural and industrial, and Christian humanity in an emergent Atlantic system of exchange, control, and propaganda. A relic of that process, Feldtrappe’s scattered lengths of toile continue to transmit intriguing and complex images, their ardent message reinforced by the cotton on which they are stamped.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Musée d’Aquitaine, Bordeaux, Musée d’Histoire de Nantes, the John Carter Brown Library, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Linda Eaton (Winterthur Museum), Tom Fiehrer, Lourdes Font (FIT), Louise Le Gall (Musées de Cherbourg-Octeville), the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYPL Rare Book Division, Debra Jackson, Lawrence C. Jennings, Hugues Pladieux, Judy Sund, Yale Center for British Art and “Object Lessons” editors Ellery Foutch and Sarah Anne Carter.

Further Reading:

This essay’s findings regarding the Fréret-Colibert attribution were originally presented at the TSA’s “Textiles and Politics” on Sept. 20, 2012, and in a Graduate Center seminar on ephemera in the eighteenth century led by Kevin D. Murphy and Sally O’Driscoll in 2009. An unpublished reference to Colibert and Amédée Fréret is noted independently in the Traite object record at Château des Ducs de Bretagne.

The following sources have supplied facts about the textile trade in the Atlantic world: Ann DuPont, “Captives of Colored Cloth: The Role of Cotton Trade Goods in the North Atlantic Slave Trade (1600-1808),” Ars Textrina, 24 (1995); Kriger, “‘Guinea Cloth’: Production and Consumption of Cotton textiles in West Africa before and during the Atlantic Slave Trade,” in The Spinning World, A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850, Riello and Parthasarathi, eds. (London, 2009); Xavier Petitcol, “Pour une approche materiélle des toiles histoires de Normandie” in Doré, Quand les toiles racontent des histories: les toiles d’ameublement normandes au XIXe siècle (Rouen, 2007); Riffel and Rouart, Toile de Jouy : Printed textiles in the Classic French Style (New York, 2003); and Yafa, Cotton: The Biography of a Revolutionary Fiber (New York, 2005). For visual references to the cloth trade in colonial Mexico see Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (New Haven, 2004).

For further information about abolitionist literature, imagery and the Atlantic slave trade see: Basker ed. American Antislavery Writings (New York, 2012); Cottias, ed. Les Traites et les esclavages: perspectives historiques et contemporaines. (Paris, 2010); Bender, Dubois, and Rabinowitz eds., Revolution! The Atlantic World Reborn (New York, 2011); Dorigny and Gainot, La Société des Amis des Noirs, 1788-1799 (Paris, 1998); Jennings, French anti-slavery: the movement for the abolition of slavery in France, 1802-1848. (Cambridge, 2000); McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Chicago, 2011); Miller, The French Atlantic Triangle, (Durham, N.C., 2008); and Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780-1865 (New York, 2000).

Background information about Feldtrappe’s print sources is found in the following publications: Baily, George Morland: A Biographical Essay (London, 1906); Collins, Memoirs of that Celebrated, Original and Eccentric Genius the Late George Morland (London, 1806) ; Collins, The Slave Trade; A Poem. Written in the Year 1788 (London, 1793); D’Oench,“Copper into Gold:” Prints by John Raphael Smith, 1751-1812 (New Haven, 1999); Fouace, “Une dynastie d’artistes: les Fréret,” April 1, 1990, La Presse de la Manche; Hubert, “L’évolution artistique à Cherbourg au XIXe siècle” in “Cherbourg et le Cotentin” (Cherbourg, 1905); For other Colibert prints see Margaret Morgan Grasselli, Colorful Impressions: The Printmaking Revolution in Eighteenth-Century France (Washington, D.C., 2003).

All of the Fréret-Colibert prints can be viewed online. Further information about Wood’s Injured Humanity is available here.

For other printed works by Feldtrappe see the website Joconde: Portail des collections des musées de France.

The Chipstone Foundation is a Milwaukee-based arts organization devoted to the study and interpretation of early American decorative arts and material culture.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.1 (Fall, 2013).

Cybèle T. Gontar is a PhD candidate in American art at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She has written for the Metropolitan Museum Journal, The Magazine Antiques, and Common-place