After spending the summer of 1890 in Venice, the American painter Thomas Moran and his wife, the etcher Mary Nimmo Moran, boarded the steamship Shelter Island to cross the Atlantic and return to their Long Island home. Accompanying them on board the ship was a seemingly odd (and cumbersome) souvenir: the nearly 36-foot-long gondola that the Morans had used during their time in Venice (fig. 1). Due to its substantial length, the gondola made the transatlantic voyage alongside the steamer’s lifeboats, hanging from the davits on the side of the ship. It was transported from New York to Sag Harbor in a similar fashion, and from there it traveled along the Long Island country roads to the Morans’ East Hampton home in a specially outfitted horse-drawn wagon. The vessel quickly became a popular local attraction: there was even an article in the East Hampton Star to celebrate the gondola’s first American voyage, when a group consisting of the Morans and two other couples enjoyed a ride around a local pond.

The gondola fulfilled a range of roles: it was a souvenir that served as a physical reminder of the Morans’ Venetian trip, a visual source that Thomas Moran could refer to in future paintings, a means of pleasurable entertainment for the Moran family, and an antique craft that had supposedly belonged to the poet Robert Browning. Although it might seem an unconventional souvenir today, the gondola, which is now in the collection of the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia, is also a rare surviving example of something that was surprisingly common at the turn of the twentieth century: Venetian gondolas in America. At their most basic level, these gondolas represented the desire to capture a bit of Venice’s mystery and picturesque culture and bring it to the United States. Yet their presence also points to a growing concern about modernization and the loss of history at the turn of the century.

From Venice to America

Born in England and raised in Pennsylvania, Thomas Moran is known for his landscape views of the American West. However, following his first trip to Venice in 1886, he devoted significant attention to painting Venetian seascapes in a shimmering, light-infused style that was influenced by the British painter Joseph Mallord William Turner. Moran was not alone in his fascination with Venice: over the course of the 1880s, a number of American artists—most famously, James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent—worked in Venice, depicting the island’s iconic canals and landmarks, as well as its most recognizable workers. Moran, however, was primarily interested in Venice’s lagoon, where boats of all shapes and sizes crossed paths in front of the city’s famed skyline.

After traveling alone in 1886, Moran took a second trip to Venice in 1890, this time accompanied by his wife. When the Morans arrived in Venice in May, they followed the common practice of hiring a local gondolier. While elite Venetian residents—both native and foreign—employed full-time gondoliers as part of their household staff, the common practice for visiting foreigners was to hire a gondolier, usually at daily or weekly rates. In addition to providing a gondola and transportation as needed, gondoliers would also perform other household duties. As the writer Constance Fenimore Woolson explained in an 1893 letter to Mrs. Samuel Mather, “In Venice your gondolier not only takes you out in his gondola … but goes to market and waits at table, blacks shoes, and brings up wood, etc.”

The basic features of Venetian gondolas have remained consistent since the nineteenth century. The boat has a flat bottom and the bow and stern are raised, giving it a shape that is often described as banana-like (fig. 2). Today’s gondolas are famously asymmetrical, with a pronounced tilt toward the starboard side. Although the asymmetry has become more pronounced over time, it originated in gondolas produced at the Casal boatyard in the mid-nineteenth century. The Moran gondola was likely built at the Casal boatyard, which could make it the oldest surviving gondola in existence.

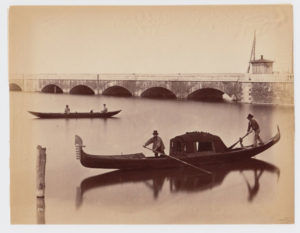

Attached to the bow is the ferro, a distinctive iron fitting whose shape loosely resembles a comb. A popular belief holds that the six forward-facing “teeth” in the ferro represent the six different sestieri, or districts, that constitute Venice. The ferro has two main purposes: it protects the bow of the gondola in the case of a collision, and it counterbalances the weight of the gondolier, who stands on a raised platform at the stern. Historically, it was common for gondolas to have two gondoliers, one each at the bow and stern. This gradually changed over the course of the nineteenth century, and nineteenth-century photographs show both single- and double-gondolier arrangements.

In Venice, the Morans hired an elderly gondolier named Giovanni Hitz, whose gondola was uncommonly ornate. In the early modern era, it was common to see highly decorated gondolas painted in bright colors. However, the passage of a series of sumptuary laws in the Renaissance limited the decoration of any gondola owned by one of Venice’s noble families (the gondolas of foreign diplomats and other non-Venetians were exempt). The gondola’s famous black color—which led Mark Twain to describe the vessel as a “hearse”—dates to these laws: the black pitch used to seal the waterproofing was the only form of color permitted.

Although enforcement of the laws concerning gondola decoration was inconsistent, the sheer number of decorative elements on the Morans’ gondola is surprising. Comparing the Moran gondola to photographs of other nineteenth-century gondolas indicates just how uncommon its level of decoration was. At the gondola’s bow, a series of pitched beams creates a raised platform; the gondolier typically stores his belongings in the enclosed space below. Photographic records show that it was common for the wooden planks closest to the gondola’s passengers to contain relief carvings (figs. 2-5). Yet on Moran’s gondola, not only the final plank, but the entire prow, is decorated with geometric and vegetal reliefs; similar decorations appear on the boat’s stern.

The interior of the passenger compartment contains more low-relief carvings (see slideshow at end of article). A panel depicting the god Neptune brandishing a trident in a seahorse-drawn chariot decorates the front of the passenger compartment. Panels containing a crowned eagle surrounded by serpentine branches adorn the interior sides of the gondola; the crown reappears atop a large monogram surrounded by plant and animal motifs, which attaches to the back of the black leather settee (fig. 6). When Moran purchased the gondola, the interior carvings were painted in black and gold. A 1999 restoration, undertaken at the historic Tramontin boatyard in Venice, saw the panels repainted in the same colors.

Although rarely seen today, in the nineteenth century gondolas were equipped with a felze—a detachable cabin, complete with a door and windows, that provided privacy and protection from the elements. Alternatively, a linen summer awning, which was more like a tarp than a cabin, could be used in warm weather. While the Moran gondola’s felze is currently in storage, it likewise contains elaborate decoration (fig. 1). Shells and arabesques decorate the exterior panels on the front and sides of the felze, and the center of the door depicts a relief carving of a bearded figure with a snake in his mouth. Even the glass windows feature etched floral motifs around the perimeter of the glass. The combination of all of these features results in a gondola that is distinctly more decorative than what would be found on a typical nineteenth-century gondola.

According to Moran, his purchase of the gondola was directly linked to its sumptuous decoration, as caring for the extravagant gondola had become a burden for his aged gondolier, Hitz. As an artist, Moran appreciated the craftsmanship of the boat’s carvings, which were, in his words, “of exceptionally artistic merit.” In a 1909 letter explaining why he purchased the gondola, Moran pointed to its decorative elements: “It was so beautiful & graceful, & so ancient & fine in its carvings, brasses, & fittings, that we fell in love with it, & decided to buy it & have it sent to our Long-Island home.” Yet the gondola—and its elaborate fittings—could also serve a practical purpose for the artist. Although Moran’s 1890 Venetian trip was the last time he traveled to the island, he continued to paint Venetian scenes for the remainder of his career, and his letters confirm that he depicted the gondola in many of his later artworks.

The usefulness of a gondola for a painter who depicted Venetian subjects was noted in contemporary newspaper accounts. News of the Morans’ return from Venice and their acquisition of the gondola was apparently of nationwide interest, as newspapers as far away as Louisiana reported on the event. An article in the Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago) on September 23, 1890, noted that “Moran tried to get it [the gondola] into the country free under the description, ‘tools of trade,’ but the Custom House thought that a duty of 45 per cent ad valorem would do better.” The subject of import taxes was again raised in an October 4, 1890, article in the New Orleans newspaper The Daily Picayune:

Thomas Moran, the artist, imported recently a Venetian gondola, formerly the property and water carriage of Robert Browning, and, it is now swimming on Redhook Pond, Easthampton, L. I. The New York custom-house people made Mr. Moran pay a duty of 45 per cent ad valorem under the schedule for manufactures of wood and metal. Think of writing down a gondola—and a dead poet’s gondola at that—as a ‘manufacture of wood and metal!’ There are some very stupid people in New York.

As The Daily Picayune noted, the gondola was more than simply an artist’s tool. Yet the article also points to another factor in the gondola’s history: its purported connection to the poet Robert Browning. According to Moran’s account of his purchase of the gondola, after he settled his affairs with the gondolier Hitz and once the boat was packed up for transit, the manager of the hotel where he was staying mentioned that the gondola had formerly belonged to the poet Robert Browning, who had died in Venice just a few months before the Morans’ trip. According to the story, Hitz had previously been Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s gondolier, and Browning gave the highly decorated gondola to Hitz before the Brownings returned to England.

The rumored Robert Browning connection to the gondola is likely false, since Browning didn’t reside permanently in Venice, and foreign visitors did not typically purchase gondolas. However, it is possible that Hitz worked for Browning’s son Pen, who had purchased Palazzo Rezzonico in Venice in the 1880s and was a full-time resident. Despite the tenuous factual connections, it is clear that Moran took some pleasure in the story and in the gondola’s possible connection to the Brownings. Although in his letters Moran remained ambivalent and perhaps more guardedly circumspect about the validity of the Browning connection, Moran nonetheless specifically mentioned his hope that Browning might have composed his poem “In A Gondola” while lounging in the gondola now in the painter’s possession.

Gondolas in America

Today, the Moran gondola’s age and location in a museum collection distinguishes it as a rare object. However, the Morans were by no means alone in their interest in gondolas: acquiring Venetian gondolas for private or public use was surprisingly common at the turn of the century. In fact, the Morans’ gondola was not even the only one in East Hampton. According to reports in The East Hampton Star, Albert and Adele Herter, a wealthy couple who were also members of the artist’s colony on East Hampton, also had a gondola, which they brought back from a wedding trip to Venice. Their gondola was a scaled-down version that was likely designed for tourists: it only measured about fifteen feet long, compared to the Morans’ thirty-six-foot behemoth. Another New Yorker, the comic actor Joseph “Fritz” Emmet, also acquired a Venetian gondola in the late nineteenth century. In his case, the boat wasn’t intended to be a souvenir. Instead, Emmet purchased the gondola as a form of leisurely transportation to be used on the man-made lake at “Fritz Villa,” his elaborate and architecturally incongruous estate just outside of Albany.

While a small number of private individuals acquired gondolas, these Venetian boats were regularly seen in public settings. As early as 1862, a gondola was donated to Central Park’s Board of Commissioners for use on the lake; although seen in use in an 1894 photograph (fig. 7), it is unclear at what point gondola rides became a regular fixture at Central Park, since initially there was no one available who could accurately maneuver the boats. In contrast, planners of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago brought fifty-seven gondoliers to the city to man the gondolas that famously floated around the lagoon in the White City.

Gondolas also became popular public attractions at Coney Island, with Luna Park and Dreamland both featuring Venetian-themed entertainment venues that included gondola rides. When Frederic Thompson and Elmer Dundy opened Luna Park in 1903, one of the main attractions was a reproduction of Venice’s Piazza San Marco and the Grand Canal, complete with gondolas. When Luna Park’s competitor Dreamland opened a year later, it also included a Venetian city (figs. 8 and 9). Dreamland’s “Canals of Venice” contained a miniature replica of Venice inside a building designed to mimic the Doge’s Palace. Visitors could travel in a gondola through the half-mile of canals and experience the sights of Venice—all without leaving Coney Island.

Not surprisingly, the development plans for Venice, California, also incorporated gondolas (fig. 10). After acquiring a parcel of marshy land south of Santa Monica, the real estate developer Abbot Kinney began creating the “Venice of America.” The resort town would include buildings in a “Venetian” style, canals, gondolas, parcels of land for homes, and eventually a hotel and amusement pier. Although most of the canals were later filled in, when Venice first opened in 1905, the resort contained several miles of canals, including a large “Grand Canal” that fed into a lake. Whether Kinney intended for the town’s residents to use gondolas to traverse the canals remains unclear. However, gondola rides were a common pastime for visitors, and images of tourists riding gondolas through the canals were regularly depicted on postcards.

Gondolas, Modernization, and Leisure

What might have prompted this interest in gondolas in turn-of-the-century America? Certainly some of it can be explained by the increasing numbers of foreign travelers who visited Venice in the nineteenth century, both on their own and as part of organized tour groups. As material objects that were inextricably linked with Venice, gondolas had long played a role in the remembrance of Venetian holidays. When wealthy young men traveled to Venice on the Grand Tour, they often returned with painted depictions of Venice, such as those by Canaletto. These views of the Grand Canal were typically populated with gondolas and gondoliers. With the invention of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, travelers began to collect photographs and photographic albums; gondolas again played a significant role in these collections. And for the large percentage of Americans who had never been to Venice, riding in a gondola at Coney Island or at the Columbian Exposition would have provided the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience a “foreign” culture without leaving the U.S.

However, another factor may also explain why gondolas began to appear across the United States in the late nineteenth century: a concern that Venice’s unique character and history was under assault. Venice in the nineteenth century was far from an unchanged relic of a preindustrial past: a railroad bridge was built in 1846, which connected the island to the mainland for the first time; a corresponding railroad station was built in the northwest part of the city in 1860. An iron bridge was constructed near the Gallerie dell’Accademia in 1854; the construction of an aqueduct beginning in 1881 eliminated the city’s dependence on well water; and in the 1880s a French company began running steam-powered boats down the Grand Canal.

While there was a general displeasure among foreigners about the changes Venice was experiencing, the presence of the steamboats caused particular distress in the English-speaking world. Following reports in London newspapers, news of the steamboats made its way to the United States, and on October 23, 1881, the New York Times described the situation: “According to our Italian correspondent, a line of steamers will in a short time be plying on the Grand Canal of Venice. This news must be a shock to the aesthetic feelings of every properly constituted mind, while its effect on Mr. Ruskin is a subject too painful to contemplate.” The article complained about “the snore of steam-boats” and expressed concern about what effect this new development would have on Venice’s gondoliers. It ended with a dramatic rhetorical flourish:

The Piazza di san Marco, the Campanile, the Torre dell’Orologio, the Doge’s Palace, the Church of Santa Maria della Salute, the Academia, the Scuola of San Rocco, the Rialto, where Shylock cozened Antonio and Othello made love to Desdemona, are there for the tourists whose finer feelings are not lacerated by a smoke-begrimed facade. But who can quote Byron with the smell of train-oil in his nostrils? And though the moon will light up, as of yore, the wondross view from the Ponte dei Sospiri, it is sad to think that it must be enjoyed in the incongruous society of a Glasgow engine-driver, who gives “her half a turn ahead” and wipes his sooty brow with a wisp of cotton waste as the funnel belches out smoke against the convent wall which guards the choicest treasures of Titian, Tintoretto, and Paolo Veronese.

Despite the article’s humorous tone, the concern about Venice’s modernization—and especially how the changes would affect tourists—is apparent. Yet although there was spirited opposition on both sides of the Atlantic, and a gondolier’s strike in late 1881, the steamboat venture would eventually be a success.

By the time the Morans traveled to Venice in the late 1880s, Venice’s gondolas were already beginning to be displaced by motorized steamboats. These ancestors of the vaporetti, or water buses, that transport tourists around Venice today originally traversed a single route on the Grand Canal. By 1899, however, Baedeker’s guide to Northern Italy listed ten steamboat routes that linked Venice with the surrounding islands. While gondola travel remained necessary in certain instances (for example, when traveling with trunks, which were not permitted on the vaporetti), riding in a gondola increasingly began to shift from a form of transportation to a leisure activity.

In many ways, the appearance of gondolas in the United States affirmed the gondola’s transition from an object of labor to one of entertainment. Despite Moran’s claim that he bought the boat for its beauty, it is clear that the Moran family also saw the gondola as a source of pleasure and amusement. Indeed, Thomas Moran joked that his gondola became a “seven day wonder” when he first brought it to East Hampton. Yet for the Morans and their guests, the “wonder” of the gondola involved the experience of riding in it as a passenger, rather than attempting to maneuver it. As his biographer Thurman Wilkins noted, “Moran developed no knack as a gondolier, but on the assumption that the canoe was the nearest thing to a gondola in America, he hired a Montauk Indian named George Fowler to be his boatsman.” Among the Mariners’ Museum files is a copy of an undated photograph showing Fowler (in a jaunty gondolier’s uniform) with members of the Moran family aboard the gondola (fig. 11). A picnic basket placed on the shore in the central foreground of the photograph reinforces the connection between the gondola and leisure—for everyone but Fowler, at least.

From America to Venice

Over a hundred years after the Moran gondola traveled across the Atlantic Ocean, it made another transatlantic journey—this time, back to Venice. In 1999, the boat, including the felze and all of its accessories, was shipped from Virginia to Venice for restoration at the century-old Tramontin boatyard, or squero. Before founding the Tramontin boatyard in 1884, Domenico Tramontin had worked as an apprentice at the Casal ai Servi boatyard, where experts believe the Moran gondola was likely made. Today the Tramontin boatyard is operated by Domenico Tramontin’s descendants, and it is one of only a handful of Venetian squeros still in operation. At the boatyard, parts of the gondola that had been previously restored were removed and replaced, new felt was applied to the top of the felze, old nails and screws were replaced with more secure versions (and, incongruously, epoxy glue) and the boat—and its decorative panels—were repainted.

Ironically, one of the main challenges the museum staff faced was the issue of transportation. Specifically, once the gondola arrived in Venice, how would they transport the hundred-plus-year-old boat—which had not been on the water in half a century—to the squero without getting it wet? Ultimately, the gondola itself was taken for a ride, traveling through Venice’s narrow side canals atop another boat. In this short trip we find a distillation of the gondola’s journey—from a boat that was itself a form of transportation for Venetian tourists like the Morans to a museum object whose transportation requires detailed planning and care. Over the course of its history, the Moran gondola has taken on a variety of roles, which reflect changing attitudes toward modernization, leisure, labor, and transportation. Yet despite Thomas Moran’s belief that his gondola was the only one of its kind in the United States, it is clear that it is, instead, a rare surviving example of a much more widespread phenomenon, in which Americans from Coney Island to California shared in the wonder of Venetian gondolas.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the staff of the Mariners’ Museum, especially Jeanne Willoz-Egnor and Claudia Jew, for their assistance with this project.

Further Reading

Thomas Moran’s Venetian trips (including his purchase of the gondola) are discussed in Thurman Wilkins, Thomas Moran: Artist of the Mountains (Norman, Okla., 1965) and the revised second edition, Thurman Wilkins and Caroline Lawson Hinkley (Norman, Okla., 1988). Fritiof Fryxell’s Thomas Moran: Explorer in Search of Beauty (East Hampton, N.Y., 1958) contains a summary of the Moran-related materials at the East Hampton Public Library and several reminiscences of Moran.

For the history of gondolas in Venice, see G. B. Rubin de Cervin, “The Evolution of the Venetian Gondola,” The Mariner’s Mirror 42:3 (Aug. 1956). Riccardo Pergolis’s Le Barche di Venezia (The Boats of Venice) also addresses the history and development of the Venetian gondola, with text in English and Italian (Venice, 1981). A richly illustrated account of the restoration of the Moran gondola at the Tramontin boatyard can be found in the magazine Wooden Boat; see Paolo Lanapoppi, “Six Centuries of Gondolas,” Wooden Boat 152 (Jan.-Feb. 2000): 42-49.

The best introduction to the history of Venice, California, is Jeffrey Stanton’s Venice California: ‘Coney Island of the Pacific’ (Los Angeles, 1993). For the history of Coney Island, see Michael Immerso, Coney Island: The People’s Playground (New Brunswick, 2002) and John F. Kasson, Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century (New York, 1978).

Margaret Plant’s Venice: Fragile City, 1797-1997 (New Haven, 2002) provides an excellent history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Venice with a focus on art and culture. The exhibition catalogue Venice: The American View, 1860-1920 (San Francisco, 1984), which was curated and authored by Margaretta Lovell, provides a good introduction to the American artists who were interested in Venice and the reasons for Venice’s appeal. For more on American artists in Italy, see The Italian Presence in American Art, 1760-1860 (New York, 1989) and The Italian Presence in American Art, 1860-1920 (New York, 1992), both edited by Irma B. Jaffe; see also Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760-1914 (Boston, 1992).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3 (Summer, 2016).

Ashley Rye-Kopec is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Delaware. Her dissertation examines depictions of Venetian laborers in British and American art in the late nineteenth century.