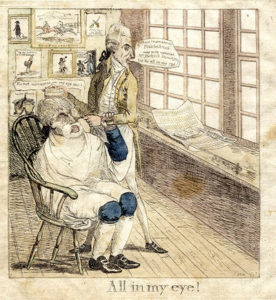

In 1806, the American caricaturist James Akin (1773-1846) published a satirical print that depicted the interior of a barbershop, with a barber and his client set against a wall filled with caricatures. Titled “All in my eye!” (fig. 1) this caricature was published in reaction to a specific event that would have been familiar to the citizens of Newburyport, Massachusetts, where Akin was at this time working as an engraver. The event struck a personal chord with Akin. In March 1806, Akin’s friend, the engraver Jacob Perkins (1766-1843), was targeted by an anonymous pamphleteer. Although Perkins retaliated in a newspaper editorial, it was Akin’s talent as caricaturist that would not be silenced. Sometime after March 1806, Akin published “All in my eye!” in defense of his friend.

We might assume that caricatures like Akin’s belonged in London, England, rather than Newburyport, Massachusetts. After all, caricatures satirizing specific events and personages were in great demand in Britain. The abundance of impressions that resulted formed a ubiquitous part of eighteenth-century British visual culture. The appetite for this particular genre crossed the Atlantic more slowly than other kinds of images. Certainly, some eighteenth-century satirical prints portraying both political and social subjects were exported from London to cities along the East Coast, where they would have been seen by Americans. William Cobbett, for example, advertised the arrival of a batch of satirical prints for sale in late eighteenth-century Philadelphia. Nevertheless, caricatures were slow to gain such acceptance in the United States. As late as the 1800s, caricatures like Akin’s, published in reaction to an event or as a personal or political attack on an individual, were uncommon.

Yet evidence suggests that if such prints were unusual, they were starting to come to the attention of a growing American consumer market. In cities such as New York and Philadelphia, printers began to issue small runs of caricatures, often similar in design and format to English satirical prints. These early American caricatures, usually unsigned, were often political in nature; anonymous artists attacked presidents, government representatives, and local politicians. And if they appealed to some buyers, they also generated a fair amount of suspicion. An opinion piece published in 1802 in the New-York Evening Post announced that, “It is with great pain we observe a species of libel has already appeared in our country in imitation of the abominable and licentious practice of the lower English, commonly called caricature, in which the unhappy object of abuse is exposed to vulgar derision… it is a species of attack equally cowardly and brutal.” This was the market that Akin entered and helped transform in the early 1800s. He published both political and social caricatures and he prominently displayed his signature on impressions, taking full ownership of his visual attacks.

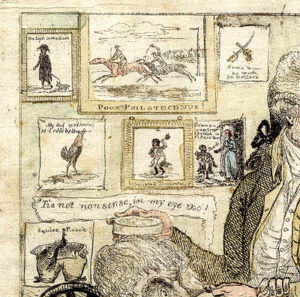

In “All in my eye!” Akin represents a barber in his shop conversing with his customer. The barber haphazardly attends to his client, although it is clear that his thoughts are otherwise engaged. The barber’s head is turned away from his client, towards the window. His gaze and the words within his speech bubble direct the viewer to a newspaper and a pamphlet on the windowsill. The pamphlet titled “An Examination of the Method of making Bills from the Stereotype” was written by a “Philotechnus,” a nom de plume for an author not yet identified. The pamphlet attacked the methods invented by Perkins for the detection of counterfeit bills. Akin includes the newspaper in which Perkins issued his defense, clearly providing the title of the paper, Newburyport Herald, as well as the date of March 7, 1806, the edition in which the rebuttal was published. On the wall behind the barber are seven prints, set in two rows of three and a single print below them (fig. 2). Three of the prints are known to have been published by Akin in 1805 and are biting satirical images on two well known figures in Newburyport. Two of the caricatures depict Edmund Blunt, Akin’s former employer, and the third depicts the eccentric Newburyport character Timothy Dexter. The other four prints may have been published, but there are currently no records of these images that survive in archives or graphic art collections.

By including references to three of his previously published satirical prints, Akin reminds viewers of “All in my eye!” that this was not the first time he had used caricature to assault his so-called enemies and foes. Indeed, Akin was actually quite successful at it. In 1805 and 1806, Akin published several caricatures that depicted, Blunt in less than flattering positions. Two of these impressions are seen on the wall of the barbershop. The widely circulated caricature, titled “Infuriated Despondency!” (fig. 3) can be seen in the middle of the wall, in reverse, while the second caricature of Blunt, “An Edict from Saint Peter” (fig. 4), is seen to its right.

In the caricature “Infuriated Despondency,” Blunt is depicted holding a three-pronged skillet, alluding to an event that occurred on October 27, 1804 between Blunt and Akin. The two men, no longer working professionally together, had a violent encounter in the Newburyport shop of Josiah Foster. Akin reportedly slapped Blunt, and Blunt retaliated by picking up the nearest heavy weapon, a skillet, and hurling it at Akin. However, instead of hitting Akin, the skillet went through the shop window, hitting an unsuspecting (and unfortunate) passerby. Akin first published this image of Blunt with the skillet as a broadside, alongside a damaging description of the event. The caricature was advertised in the Newburyport Herald in 1805 and in 1806, and Akin sent the design to England, where the caricature of Blunt and the skillet was placed on Liverpool pottery, including chamber pots. The pottery was sent back from England to Newburyport, where it was distributed amongst the local citizens. Blunt’s family and friends bought as many pieces of the pottery as they could find, although there are a few rare examples known to exist.

The other satirical print of Edmund Blunt is entitled “An Edict from Saint Peter” in which Blunt is shown being sent away from St. Peter’s Lodge, where Freemasons met in Newburyport. Blunt was a freemason before resigning in 1802 for unknown reasons. This caricature is rare and does not appear to have been as widely circulated at “Infuriated Despondency.” However, it most likely would have been seen in Newburyport, and the incident of Blunt’s removal as a freemason and the circumstances surrounding such an event would have been the source of much gossip.

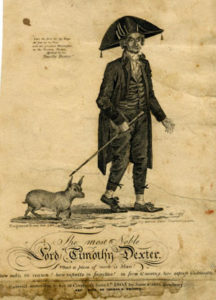

The third caricature represented, also shown in reverse, “The Most Noble Lord Timothy Dexter” (fig.5) is the first caricature in the first row on the wall. This image depicts the eccentric Newburyport man Timothy Dexter, known in the town for faking his own death and for claiming that his wife, very much alive and living in his home, was in fact dead. Akin first published this caricature in 1805, depicting Dexter in his bizarre costume, carrying his cane and shown walking with his hairless, short-legged dog. Dexter’s famous words, “The First in the East,” are made prominent in this caricature within a caricature, shown above the head of the man and his dog. While it is not known what their relationship may have been, Akin’s critical design of the man was a successful one. It was reprinted several times in 1805 and 1806. Like “Infuriated Despondency” this satirical print appears to have been widely circulated and was advertised in the Newburyport Herald.

When “All in my eye!” was published in 1806, James Akin already had a reputation as an engraver and caricaturist. Akin was born in South Carolina in 1773 and travelled to London in 1798 for a short period, where he claimed to have studied with the Royal Academy’s President, Benjamin West. Upon his return to America, Akin worked as an engraver in Philadelphia, before moving in 1804 to Newburyport, some forty miles northeast of Boston, to work with Blunt. Sometime before Akin journeyed north to Massachusetts, he made the acquaintance of Jacob Perkins in Philadelphia, although details regarding their meeting are not known. In 1799, Perkins placed advertisements in newspapers announcing his invention that could detect counterfeit bank paper, and included a list of “eminent artists in Philadelphia,” including Akin, who had tested his invention. An opinion piece published in a New York newspaper that same year also noted that Perkins had enlisted the “the most celebrated engravers in the United States” to test his invention. Although it is known that Akin left Philadelphia to work with Blunt in Newburyport, it must have been a relief for Akin to know that his good friend Perkins lived in the same town. When Akin and Blunt parted professionally in 1804, Akin relied on his Newburyport friend, often referring to Perkins in his advertisements.

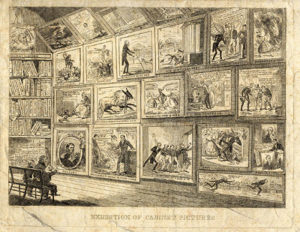

The caricature “All in my eye!” is an important document for the study of the early history of American graphic humor. It is the earliest known caricature to have been published that includes within its impression an artist’s previously published work, an early form of marketing. The closest related caricature is by David Claypoole Johnston in 1831 of “An Exhibition of Cabinet Pictures” (fig. 6), in which Johnston represents his own work within the larger print. There is evidence found in contemporary accounts that prints of landscapes and portraits of political figures were displayed in shop windows. However, we do not have any visual evidence of American audiences viewing caricatures in this manner. This is in contrast to the subject matter of satirical prints that dominated London during the so-called “Golden Age of Caricature.” British caricaturists depicted how the London public came to view caricatures by satirizing shop windows filled with social and political satires, contributing a commentary of mockery on the British social classes. One example can be seen in “Caricature Shop,” published by P. Roberts in 1801, in which the exterior of the publisher’s shop and the crowds that have come to view the new prints displayed in the window are represented in caricature. As Akin was in London in the late 1790s, it is likely that he not only would have seen such caricatures, but he would have stopped to look at publishers windows and attended print exhibitions, examining the newly printed caricatures.

“All in my eye!” is thus an American example of early nineteenth-century marketing techniques. Akin was incredibly adept at marketing his own caricatures, frequently advertising new impressions in local newspapers. Advertisements published in the early 1800s indicate that at least one of Akin’s political caricatures was on at least one barbershop’s walls in New York City: John Richard Desborus Huggins, a New York City barber, advertised that his shop walls were adorned with caricatures, and included a description of a satirical print published by Akin representing Thomas Jefferson. Akin also sought larger, more far-flung audiences. In 1805, he explored the possibility of binding his caricatures in a portfolio. It isn’t clear whether he succeeded, but he went as far as submitting a title for a book of plates to be published, including the references to 25 specific works. Although “All in my eye!” is not one of the works mentioned (it had not yet been published) the three caricatures discussed here are named on the list. While there is more to be gleaned from such a caricature, like so many other satirical prints of this period, allusions made by the artist are often lost to a modern viewer. Akin provides an excellent study in marketing his own prints, while also attacking a contemporary enemy, two things Akin was clearly successful at achieving.

Further reading:

For a survey on the caricaturist James Akin, see Maureen O’Brien Quimby’s article “The Political Art of James Akin” in Winterthur Portfolio (January 1972). For more on Akin’s time in Newburyport, consult “James Akin in Newburyport” by Lewis C. Rubenstein in Essex Institute Historical Collections (1966): 102. For more on the specific caricature “Infuriated Despondency!” and its representation on pottery, see Nina Fletcher Little’s article “The Cartoons of James Akin upon Liverpool Ware” in Old-Time New England, (January 1938): 28.

For an overview of American caricature consult William Murrell’s A History of American Graphic Humor (New York, 1933), especially volume one, and Frank Weitenkampf’s American Graphic Art (New York, 1924). An excellent study on British caricature from this period is Diana Donald’s The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III (London, 1996).

The only book dedicated to the life of Jacob Perkins is Jacob Perkins: His Inventions, His Times, & His Contemporaries, by Greville and Dorothy Bathe (Pennsylvania, 1943). Further information on Edmund Blunt and Timothy Dexter, as well as a short biography of Akin, can be found in volume two of the History of Newburyport, 1764-1909 by John J. Currier (Newburyport, Mass., published for the author, 1909).

This article originally appeared in issue 10.2 (January, 2010).

Allison Stagg is a graduate student in Art History at University College, University of London. She will be submitting her Ph.D. in 2010 on political caricature published in the United States between 1787 and 1830.