The color line in The County Election

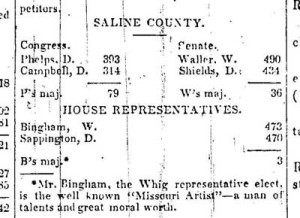

When Missouri artist George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879) was at work on his most popular and complex paintings he was also deeply engaged in Whig politics. Bingham was already well known for his genre scenes of riverboat men and frontier life—Fur Traders Descending the Missouri (1845); The Jolly Flatboatmen (1846); Boatmen on the Missouri (1846); among others—when he decided to run for state office in 1846. He had been involved in Whig electoral politics since the early 1840s, when he painted banners and delivered speeches on behalf of William Henry Harrison and Henry Clay. Bingham especially admired Clay of Kentucky, whose fiery orations compared Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren to Caesar, Cromwell, and Napoleon as usurpers of executive privilege and destroyers of the people’s independence. In 1846, fearing Missouri’s enslavement to a Democratic majority, Bingham himself ran for the state legislature as a Whig candidate from Saline County. He lost the race in a bitter post-election appeal. But the razor-thin election became the subject of his best-known political painting The County Election (1851-1852).

Given Bingham’s politics, it is not surprising that Whig ideals have dominated discussion of The County Election. What is much more surprising, however, is the degree to which scholarly attention to Bingham’s Whig rhetoric has sidelined the racial, ethnic, and class codes upon which that rhetoric depended. The County Election is a political parody that refers specifically to the Saline County election of 1846 in which Bingham ran against local Democratic favorite Erasmus Darwin Sappington (fig. 1). Sappington himself is represented in the painting as the obsequious party hack, tipping his hat to voters and proffering his card, while the portly election judge swearing in a voter at the window is Sappington’s own brother-in-law, former Missouri governor Meredith Marmaduke. The painting also parodies the men in the crowd, who are divided (a la the great eighteenth-century English artist and political satirist William Hogarth) by the moral valence of their characters: some men (the sober Whigs) read newspapers, debate or deliberate, write or draw, vote or wait quietly in line—while others (the Saline County Democrats) drink, recover from fighting, serve drinks, carry drunken voters, pander for votes, gamble, or run the election.

Because The County Election satirizes antebellum politics at a time when Missouri suffrage embraced all adult white men, it was initially charged with elitism. To counter this charge, art historians Nancy Rash, Gail E. Husch, and Barbara Groseclose argue conclusively that while The County Election parodies antebellum (and especially Democratic) party politics, it is fundamentally populist. The painting, they argue, asserts the artist’s republican faith in the voice of “the people,” the Union, and government by representation, despite corruption by party hacks, fixed elections, drunken voters, and physical intimidation.

But this emphasis on Bingham’s Whig populism has obscured a second story contained within the famous work. In his study of race and labor in antebellum St. Louis, social historian Daniel Graff points out that in central Missouri socioeconomic alliances between bourgeois and working-class white men were buttressed by the color line. From St. Louis to Saline County, political solidarity across differences of class and culture was intimately tied to racial apartheid, or shared whiteness. While the racial dynamics of working-class politics are typically associated with Jacksonian Democrats, the Whig populism of The County Election is structured by precisely this kind of cross-class and multi-ethnic alliance, grounded in whiteness.

Every viewer of Bingham’s painting notes the African American man (who, we will see, was most likely a slave) on its far left margin, serving alcohol to a happy, drunken, white man. And art historians invariably identify the red-haired workingman “taking the book” at the voting window at the top of the stairs as Irish, according to the physiognomic codes and ethnic stereotypes of the period. But, in fact, the African American man on the painting’s margin and the Irish voter at its center work together in the painting’s design. Standing in the sun at the top of the stairs, with his hand on the holy book, the white ethnic voter represents the unmediated “voice” of the people—albeit a voice overwhelmed elsewhere in the painting by the ill-effects of drink. That the drunken Democrat at the drinking table happens to be receiving his drink from a slave establishes an allegorical relationship between enslavement and drink. Alcohol, in effect, enslaves the voter. What are we to make of Bingham’s temperance message? More important, what are we to make of this use of race and slavery on behalf of the familiar Whig perspective on drink? To answer these questions, we must begin with the social history of Bingham’s Missouri.

The Paperless Voter

After the “internal” Missouri Compromise of 1821, which granted universal adult white male suffrage and guaranteed the legality of slavery, the racial and social dynamics of the state changed dramatically. Among the consequences of the compromise was a new and much harsher slave regime. Throughout central Missouri, town ordinances, city police, and vigilante “patrols” required passes, ejected or arrested unfamiliar freedmen, broke up African American social gatherings, and punished the owners of slaves who too freely hired them out. As African American workers experienced these new restrictions, propertyless white workingmen found themselves enjoying the fruits of their recently won right to vote. They were actively courted by the Missouri Democrats (as one might expect) and later by the Whigs. By the time Bingham made The County Election, his party had long been courting the white workingman vote. And in Missouri, doing so meant cloaking the Whig platform in a familiar rhetoric of whiteness.

The role of class and ethnicity in The County Election is clarified by an oration Bingham delivered in Jefferson City after losing the Saline County election of 1846 to Sappington. Bingham had initially won the election in the popular count, by the extraordinarily narrow margin of three votes. But as soon as Bingham’s victory was announced in the Columbia Statesman (fig. 2), Sappington declared himself the winner and, with the support of his brother-in-law, appealed the results to the legislature, where Democrats were in the majority and where he was assured of easy victory. Rejecting Bingham’s call to take the vote back to “the people” of Saline County, Sappington’s allies worked through a legislative committee to prove that at least four of the votes for Bingham were illegal. These included the vote of an aged Irishman named Murphy.

Printed in six columns of the Boonville Weekly Observer (March 11, 1847), Bingham’s speech decries the disenfranchisement of army veteran John Murphy who had fought with William Henry Harrison in the War of 1812. Now, “grown grey in the service of his country,” the old soldier’s vote had been rejected by the Democratic legislature on the grounds that he had lost his naturalization papers. Murphy had once possessed his discharge papers with the date of his naturalization. But, Bingham explained, “these discharges, with his naturalization papers, were destroyed by an unforeseeable accident.” On these grounds, the Democrats had rejected the Irishman’s vote, because he lacked written proof that he was “twenty years of age when he took the oath of allegiance.” On this tenuous thread, the state had disenfranchised a veteran who epitomized the very spirit of revolutionary independence.

[W]hen many of us now assembled…were yet reposing in our mother’s arms,…when British bayonets brightened on every side, and the tomahawk and scalping knife glanced in the lurid glare by the savage torch—then, then, it was sirs, that the man whose right, yes, whose right of citizenship I am now defending stepped forward as a volunteer, and bared his bosom to the blast.

Three years after making this speech, Bingham revisited the story of Murphy’s disenfranchisement in The County Election by picturing an Irishman—without papers—encountering election judge Marmaduke at the voting window. In addition, the painting juxtaposes the young Irishman at the window with an old man immediately below him, who, with bent back, descends the stairs after voting. In preparatory drawings for the painting,Bingham sketched this same aged character, with the revolutionary number ’76 on his hat. The grizzled figure of “Old ’76” was a commonplace of antebellum visual culture. By juxtaposing the red-haired Irish voter with the old veteran below, the painting condenses the past and present moments of Murphy’s story while recalling its moral: the worthy voter deprived of his rights (as Bingham had been) by the Democratic “clique” of central Missouri.

In the painting, the Irishman lacks papers of any kind. Having mounted the stairs, he is preparing to vote viva voce, consistent with state election law. Under the viva voce system a vote could be delivered either orally or in writing. Upon hearing or reading a voter’s choice, the judge then announced the voter’s name and his vote viva voce—or orally and audibly—to the clerks behind him, who then recorded them in poll books. Election judges were empowered to decide the legality of any voter. If an immigrant had lost his naturalization papers or a voter appeared too young or lacked proof of residency, the judge could then administer an oath. This is precisely what occurs in The County Election where the election judge swears in the Irish voter before accepting and announcing his vote.

Missouri was among the last states to abandon viva voce voting (in 1863), along with Arkansas (1854), West Virginia (1861), Virginia (1867), Oregon (1872) and Kentucky (1891). Although the practice was established to give voters assurance that their actual votes were recorded, it also invited ethnic profiling, bullying, bribery, and its own kinds of inaccuracies—as, for example, when large crowds of voters overwhelmed clerks with their cacophonous shouts. What is significant about viva voce in The County Election, however, is that the required oath sworn by the Irish voter elevates him within the painting’s visual rhetoric as an exemplar of “the people’s” original voice.

Coatless and hatless, at the apex of the painting’s pyramidal composition, the white ethnic workingman is a visual version of the theological motto of the American Revolution—vox populi vox Dei (the voice of the people is God’s voice). Reaching hopefully for “the book,” of the law or the Holy Bible, the man summarizes the painting’s logocentric faith in representative government as a mysterious ritual of incarnation where voting—either orally, or with paper and pencil—guarantees the presence of the voice, and thus the voter, in the vote.

But Bingham’s painting is also deeply ambivalent about the voter’s representation through writing. Writing unfolds in the shady space behind the voting window, where a clerk ambiguously sharpens the point of his pencil to either faithfully inscribe or to alter the election returns. The painting’s concern with faithful inscription is also communicated by the man reading a newspaper at far right and by the voter/artist seated on the lower steps in the center foreground. With pen and paper on his knee, this figure is usually (and rightly) identified as Bingham himself: as he writes, or sketches, two voters peer over his shoulder to watch which way the vote (or drawing) will go.

By picturing the artist, The County Election posits a relationship between the honest voice of the rejected Irishman and the pencil of the highly literate Whig artist, who uses Murphy’s story to articulate his own claims to faithful inscription. Grounded in the vox populi of the disenfranchised immigrant, The County Election projects a cross-class alliance between the bourgeois Whig and the white ethnic voter he claims to represent. Intimately associated with Bingham’s own disenfranchisement by the Democratic legislature, the Irish workingman is elevated at the moment of his assimilation to a text-centered legal and electoral system that claims to represent all white men across differences of education, class, and culture.

Black Work

On April 28, 1836, a mulatto steamboat cook from Pittsburg named Francis McIntosh was burned alive in the streets of St. Louis by a white mob. Just off the steamboat Flora, McIntosh had allegedly killed a white policeman while the latter was arresting two of his companions for fighting. No one among the more than one thousand people present at the lynching was indicted. While the mob’s lawlessness was widely decried (by twenty-seven-year-old Abraham Lincoln, among others), St. Louis officials claimed that popular justice had trumped the letter of the law. In an infamous extension of the logic of popular sovereignty, the astonishingly well-named Judge Luke Lawless argued that the lynching mob had been so large that it must have embodied the authority of the people themselves and could not, therefore, be punished by the courts.

The lynching of McIntosh is an example of the racial panic that could be induced in the 1830s by the presence of free black workers in the Upper South, especially after Nat Turner’s rebellion (1831). City law simply exacerbated the problem. While black codes and blue laws constrained the movement and behavior of free blacks, they rarely impinged on the affairs of white workers. A strike and its attendant social gatherings by the city’s Workingman’s Party would have been inconceivable for black workers. By excluding free blacks from public spaces, in other words, city law effectively made St. Louis politics white.

Antebellum racial panic in Missouri reflected white anxiety about slave revolts, abolitionist print culture, and northern economic power. But such panics were also stimulated by the everyday dependence of Missouri’s commercial and river economy on African American workers—from dockworkers and draymen to smiths, cooks, barbers, and bootblacks. Moreover, economic dependence implied social contact, calling attention to the reality of relationships (of identity as well as difference) between black and white races. This equivocal repression of, and reliance upon, black work is illustrated by an 1836 print satire of a black “strike”—published in the St. Louis Literary Register just three days before the lynching of McIntosh. Reprinted from a New York paper, the satire’s central purpose is to ridicule an African American bootblack named “Scip” who is attempting to strike in imitation of white laborers in New York, Philadelphia, and St. Louis.

When the bourgeois narrator approaches his bootblack to have his boots cleaned, he learns that Scip has decided to strike. Scip reports that all the other bootblacks are out on strike and that he will now require a shilling for shining shoes. “Oh Boss,” said he, “I’ve struck!…—can’t black boots for sixpence—muss hab a shillum…“ White and well-educated, the narrator refuses to pay.

“Oh, but Scip, I am an old customer; you won’t raise on me. I’ll send my boots with a sixpence, and do you mind, make them shine like a dollar.”

“Yes, boss, I’ll brush ’em a sixpence worth.” Not doubting but they would be returned in decent order, we were not a little surprised to find them in the hall next morning, one of them shining like a mirror, and the other covered with mud, with a note stating that he intended to assist the chimney sweeps in their turn out.

—”STRIKE EXTRA,” N.Y. Commercial Bulletin report in the Missouri Literary Register 25 (April 1836)

The effect of this exchange is to affirm the whiteness of both labor and bourgeois culture by highlighting the absurdity of a striking bootblack. Scip introduces the possibility of economic enfranchisement for black workers. But the joke hinges on the impossibility of a black strike or a black workingman, in a world where the only work that counts is free white labor. If we accept that he is a slave, this same oxymoron of “black work” defines the place of the African American man in The County Election.

Given the history of Saline County, it is difficult to imagine that Bingham intended the man to be anything but a slave. Saline County was in the heart of “Little Dixie,” a seven-county area of central Missouri known for its hemp and tobacco farms, and reliance on slave labor. According to historian Thomas Dyer, the county was “home to…almost five thousand blacks” in the late 1850s, “virtually all of whom were slaves. The slave population grew by 79 percent during the decade of the 1850s, by far the greatest increase of any county in Little Dixie, the area of heaviest slave ownership in the state.” Bingham’s home of Arrow Rock, the town pictured in The County Election, was the most important river port in Saline County. By 1860 Arrow Rock had a population of more than one thousand people, nearly half of whom were African Americans.

When Bingham associates African American slavery with drinking he does so in part to imply that Democrats are enslaved. His satire implies that Sappington, Marmaduke, and their allies have corrupted the county election, not only by manipulating the letter of the law but by substituting false “spirits” for the Whig spirit of republican independence. Their senses distorted by drink, the Democrats cannot possibly exercise their franchise in a free or disinterested fashion. Instead, it is the alcohol and the party hirelings dragging drunks to the poll that are voting.

The race of the Saline County slave tars the white Democrat at his table, not only by association with drunkenness but with blackness as well. Like the abject and beaten man on the opposite (far right) side of the painting, the drunk in the painting’s left foreground is positioned at the far edge of the white political community. While the white drunk does not exactly fraternize with the black servant, the plate of meat bones before him suggests he has been at the table for some time. As a site of social contact between a black slave and a white voter, the drinking table implies social, racial, and sexual degradation at the limit of white law and order—where mixed-race social contact violates the prohibition on racial and gender mixing in street gatherings or in leisure pursuits.

Bingham’s allegory of drinking as enslavement is neither pro- nor antislavery per se. Nor is the figure of the slave racist by itself. Antebellum newspaper satire could be much more virulently racist than The County Election, as proved, for example, by countless antebellum parodies of Lincoln as a black ape. In the Whig press too, cartoons of Irish Catholic voters were far more ethnocentric and racialized than Bingham’s Irish voter. But Bingham, nevertheless, engages in racist political parody by deploying an African American body to satirize his white political enemies, by associating them with blackness or with becoming black through contact.

Moreover, the linking of blackness with drink and degradation is carried across the entire canvas, through the three stages of decline that constitute the painting’s temperance narrative. Moving from left to right, the first stage is represented by the white man at the cider table; and the second, by the drunken voter held up by another man (in the left middle ground); while the third stage is represented by the beaten and bloodied voter alone on the bench at far right. Art historians have noted the temperance narrative in the painting. But what makes it especially significant is Bingham’s insinuation of race by way of the slave with whom it begins.

While the black man introduces the topic of slavery, the fact of racial apartheid and the threat of abolition are subsumed by the painting’s temperance allegory—which associates drunken Democrats with moral enslavement and racial blackness but not with slavery in particular or the legalized violence that enabled it. With the message that Democrats are (drunken) slaves, the impulse of antislavery is sidelined and contained by the less divisive Federalist topos of republican virtue, as practiced by the comparatively sober and upright (Whig) voters. By contrast, the upright and sober slave at the cider table is tainted by the racist implication that even an African American slave is more virtuous than a white drunk—or a Missouri Democrat.

In Bingham’s political parody, race and temperance are deployed together in keeping with the black codes and blue laws of central Missouri where, between 1836 and 1859, racial violence and moral panics unfolded together within the field of white solidarity. Between 1853 and 1859 Saline County and adjoining Pettis and Carroll counties endured seven white-on-black lynchings. As in the lynching of Francis McIntosh, these acts were construed by their white participants as acts of popular justice. In Arrow Rock, for example, over one thousand people turned out for the 1859 lynching of an unnamed slave “owned by Dr. William Price,” who was accused of molesting a twelve-year-old white girl.

Whatever Bingham may have thought of these appalling events, he knew slavery well. When his own family immigrated to Saline County in 1823, they brought several slaves with them from Virginia. When the artist began work on The County Election, he owned “a male and female slave,” and in 1853 he bought four more. Nonetheless, Bingham’s overarching political concern was to preserve the Union through peaceful compromise. The artist’s enemy was anyone, be they abolitionist or proslavery Southerner, who threatened the law and order of the federal system. Hence, as the conflict over slavery intensified and the Whig party disintegrated, Bingham allied himself with Lincoln and “the Black Republicans.” When war came, he served the Union in Missouri.

In 1846, when he first ran for political office, Bingham probably did not foresee the collapse of his party. The Whigs had tasted national victory in 1840, with Harrison’s Log Cabin Campaign. And when Bingham began to paint The County Election, Missouri was four years away from the electoral chaos and violence that erupted with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It is in the Log Cabin spirit of Whig popular politics, then, rather than as a prelude to Civil War, that The County Election celebrates white male solidarity across class lines. Nevertheless, the reasons for the party’s collapse are evident in the painting. While many factors explain the Whigs’ disintegration after 1854, they include the party’s deeply equivocal relationship to economic and racial inequality, as well as the abject failure of either Whig populism or legislative compromise to adjudicate, or even address, the black codes of antebellum political life upon which white power relied.

Further Reading:

Social historians of voting such as Stuart Blumin and Glenn Altschuler, Rude Republic: Americans and their Politics in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, N.J., 2000), have commented usefully on the frequent and misleading reproductions of The County Election, in textbooks and on monograph covers, where the painting is deployed ideologically as evidence of some golden age of voting in the United States or a never-again-matched period of political participation (albeit among adult white men). But for a detailed voting history that considers viva voce voting alongside the wildly diverse, ethno-cultural attitudes and practices of antebellum voting in Missouri and elsewhere, there is no better source than Richard Franklin Bensel, The American Ballot Box in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, 2004).

Daniel A. Graff’s “Citizenship and the Origins of Organized Labor in St. Louis,” in Thomas M. Spencer, ed., The Other Missouri History: Populists, Prostitutes, and Regular Folk (Columbia, Mo., 2004): 50-80, is essential to seeing the centrality of racial apartheid in The County Election; Thomas G. Dyer’s exemplary account of lynching in Saline County, “A Most Unexampled Exhibition of Madness and Brutality: Judge Lynch in Saline County, Missouri, 1859,” in W. Fitzhugh Brundage, ed., Under Sentence of Death: Lynching in the South (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1997): 81-108, provides the data for situating Bingham’s art within the history of Saline County. Arrow Rock historian Michael Dickey has also just published a comprehensive history of Arrow Rock that draws on scattered sources to document the town’s emergence on the commercial frontier of the Santa Fe Trail and Missouri River, Arrow Rock: Crossroads of the Missouri Frontier (Arrow Rock, Mo., 2004).

Former slaves have also narrated the history of “Little Dixie.” Many of these oral histories were collected by the Federal Writers Project (WPA) in the late 1930s and are accessible online through the National Archives Website, Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers Project. Three WPA narratives from Saline County—including the memories of a child of one of Judge Meredith Marmaduke’s slaves—are also reprinted at the roots Website) as “Slave Narratives of Saline County.“

The art historical scholarship on Bingham is abundant. Students of Bingham’s election paintings should begin with Nancy Rash’s The Paintings and Politics of George Caleb Bingham (New Haven, Conn., 1991); both versions of Gail E. Husch’s article “George Caleb Bingham’s The County Election: Whig Tribute to the Will of the People,” in Mary Ann Calo, ed., Critical Issues in American Art, A Book of Readings (New York, 1998): 77-92, revised by the author from the American Art Journal 19:4; and the entire 1990 exhibition catalogue George Caleb Bingham (St. Louis, 1990), which includes essays by Barbara Groseclose, Paul C. Nagel, and John Wilmerding, among others. For a comprehensive checklist of Bingham’s paintings and sketches, including the sketch of “Old ’76” descending the stairs in The County Election, see John Francis McDermott, George Caleb Bingham, River Portraitist (Norman, Okla., 1959).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Laura Rigal is an associate professor of English and American studies at the University of Iowa. She is completing a study of the relationship between icons of American visual culture and U.S. territorial and economic expansion, Picturing Entitlement: Rhetorics of Expansion in American Visual Culture, 1776-1900.