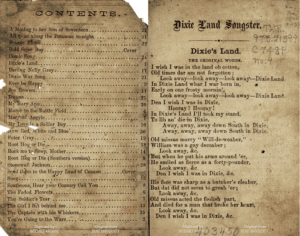

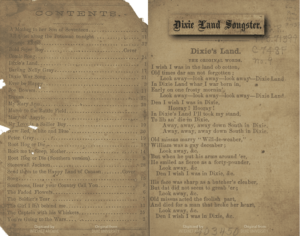

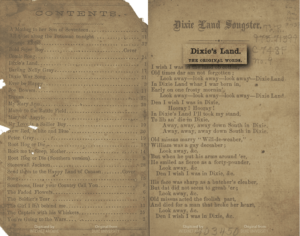

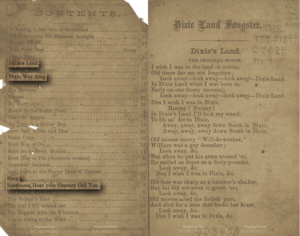

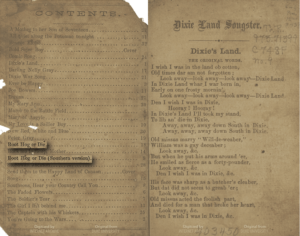

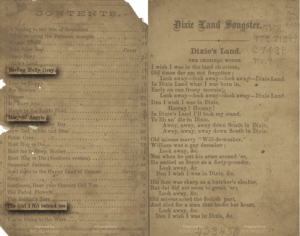

Dixie Land Songster

As the preceding slides suggests, Confederate songsters did not shy away from “foreign” material. For instance, “Mary […]

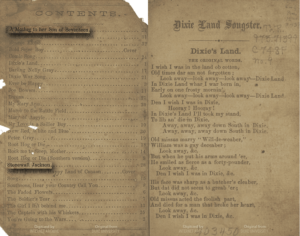

“Darling Nelly Gray” is also a song of longing, but its inclusion in a Confederate songster is surprising given that it was written by Benjamin Russell Hanby, an ardent abolitionist. The song tells the woeful tale of an unnamed Kentucky slave whose lover, Nelly Gray, has been sold further south. Even in The Dixie Land Songster version, the lyrics are in the first person, meaning that a Confederate reader might find him- or herself singing, “Oh! my poor Nelly Gray, they have taken you away / And I’ll never see my darling any more. / I’m sitting by the river and I’m weeping all the day / For you’re gone from the old Kentucky shore.” Would Confederates have missed the irony of such a performance? (After all, southerners would have been the “they” who took Darling Nelly Gray away.) Perhaps. Or perhaps not. It is possible that Confederates simply ignored the political message of the song and enjoyed its lilting melody and somewhat vague, Christian lyrics.

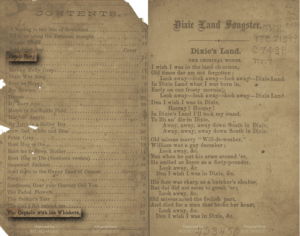

Blackface minstrel airs, British folk tunes, and patently abolitionist songs: such is the stuff of Confederate songsters, which provide a heterogeneous record of literary and musical nationalism in the making. As Confederates struggled to imagine a new political community, popular song had a particular purchase on the hearts, minds, lips, and ears of new southern nationals.

But these songsters also embody a paradox. Though partisans of a white-supremacist, pro-slavery, and anti-democratic republic, Confederates seem to have been more or less comfortable with an admixture of diverse genres, traditions, and sources—especially if that admixture could be used for Confederate nationalist ends.

Such irony wasn’t lost on one pro-Union reader. The Boston Athenaeum’s copy of the Third Edition of the Bonnie Blue Flag Song Book—another Blackmar and Brother publication—includes a particularly agitated piece of marginalia. Next to the lyrics for “Annie Laurie,” another Scottish folk song, someone has written “stolen—how mean to try to palm this off as Southern Literature!” It may have been mean but it was also wholly commensurate with the rather messy musical, popular, and print cultures of the American Civil War.

Further Reading

Much of the best work on songsters has emerged from bibliography and folklore. Irving Lowens’ Bibliography of Songsters Printed in America Before 1821 (Worcester, Mass., 1976) is an excellent starting point, despite its tight historical frame. Foundational pieces of folklore include Alfred M. Williams’s “Folk-Songs of the Civil War,” The Journal of American Folklore 5:19 (1892): 265-283, and Cecil L. Patterson’s “A Different Drum: The Image of the Negro in the Nineteenth-Century Songster,” CLA Journal 8 (1964): 44-50.

Christian McWhirter’s recent Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2012) is the best single-volume study of the “Singing Sixties.” Kirsten M. Schultz’s essay “The Production and Consumption of Confederate Songsters” in Mark A. Snell and Bruce C. Kelley, eds., Bugle Resounding: Music and Musicians of the Civil War Era (Columbia, Mo., 2004): 133-168 usefully distills her excellent and exhaustive doctoral dissertation. I have also written at length about Confederate literary nationalism in general and “Dixie” in particular: Apples and Ashes: Literature, Nationalism, and the Confederate States of America (Athens, Ga., 2012).

On the relationship between popular poetry and song, see Ray B. Browne’s early study “American Poets in the Nineteenth-Century ‘Popular’ Songbooks,” American Literature 30:4 (1959): 503-522 and Michael C. Cohen’s engaging essay “Contraband Singing: Poems and Songs in Circulation during the Civil War,” American Literature 82:2 (2010): 271-304. And Faith Barrett’s To Fight Aloud Is Very Brave: American Poetry and the Civil War (Amherst, Mass., 2012) shouldn’t be missed.

Finally, there are important collections of songsters at the American Antiquarian Society, the Boston Athenaeum, the Huntington Library, and the University of Texas at Austin, among many other archives.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.3 (Spring, 2014).

Coleman Hutchison is an associate professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Apples and Ashes: Literature, Nationalism, and the Confederate States of America (2012), and the co-author of Writing About American Literature: A Guide for Students (2014). Hutchison is currently at work on a cultural biography of “Dixie.”