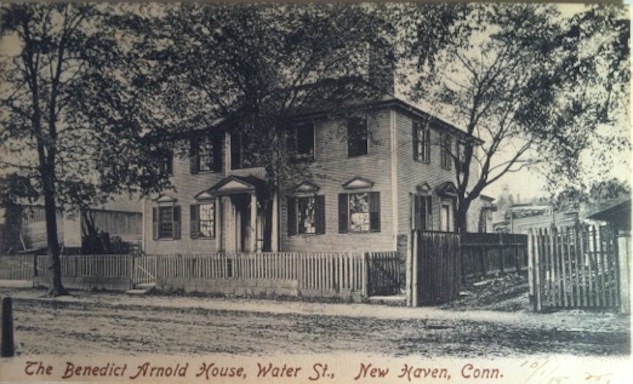

This silver communion cup, made around 1715 by English silversmith John Dixwell for the First Church of Deerfield, Massachusetts, was likely used in a Puritan communion service.

Communion in Deerfield would have looked something like this: the congregation gathered in the meetinghouse, sitting in pews facing the minister at the center of the room. Stepping down from the pulpit to the communion table, the minister blessed a flagon of wine, symbolizing the blood of Christ, and poured its contents into an array of silver vessels, including this two-handled cup. Deacons carried the cups of wine to the ends of the pews. One by one, those members of the congregation who had been declared fit to take communion passed the cup along the pews. They drank and meditated on the body of Jesus Christ and on the body of the congregation.

Behind this ritual lurked the shadow of another, the Catholic mass, in which a priest consecrated wafers and wine, transforming them into the body and blood of Christ. In the Puritan communion service, the substance that communicants ingested was merely a metaphor; in the Catholic Mass, communicants consumed the product of a miracle called transubstantiation. Although Puritans designed their service in direct opposition to the mass (and similar Anglican practices back in England), its practitioners’ version of the Lord’s Supper had more in common with the mass than Puritans wanted to admit. The silver communion cup embodied the tensions that Puritans faced in their religious experiment in New England. The cup fostered community as it enabled bodily contact between communicants and Christ. At the same time, however, communion ritualistically excluded outsiders. These tensions took on a fierce urgency as the Puritans warred with their French Catholic neighbors to the north in Canada.

Taking Communion

The Dixwell communion cup forged ties between the bodies of communicants and the body of Christ. It fit easily in the hand, with two handles that allowed communicants to pass it along the pew. Other Puritan vessels of the time would have been more difficult to hand down the pew, as they had only one handle or none at all. The Dixwell cup was designed to be handled by large groups of people, without any spilling of wine; however, the sheer delicacy of the handles (likely replaced at a later date) still encouraged users to grasp it carefully. In the Catholic mass, the priest placed consecrated wafers on the tongues of believers. By contrast, the Puritan communion service, in a manifestation of the priesthood of all believers, granted the communicant direct contact with the blood of Christ: communicants raised the lip of the cup to their own lips and drank.

Made to be touched, the communion cup both facilitated contact between bodies and formed a body of its own. Bodies are vessels, containers of viscera, and the communion cup enclosed a substance that purported to be the essence of life itself. As a metal, silver warms in contact with heat. Puritan communicants would have warmed the communion cup, and maybe the wine within, with their hands as they passed the cup down the pew. The cup and the wine sloshing within might have felt like a pulsing, living thing. Even so, the handles of the Dixwell cup prevented users from touching the body of the cup, much less the precious wine within; the contact between the body of the consumed and the body of the consumer was well-regulated.

Defining Communities

Just as the cup regulated contact between the body of the communicant and the body of the consumed, Puritans and Catholics drew different boundaries around their communities of communicants. In order to take communion at mass, Catholic communicants needed to have made confession of sins, fasted since midnight the night before, and expressed faith in the miracle of transubstantiation. By contrast, many Puritan congregations “fenced” the communion table, allowing only certain laypeople to take part. Potential members had to complete an extensive devotional regimen before the congregation deemed them ready to take part in the Lord’s Supper. Early in the seventeenth century, only those who had publicly declared their conversion experiences were allowed be baptized and take communion. By the late seventeenth century, church authorities began to allow people who had not announced their conversion but who lived godly lives to participate in the sacraments. A sometimes uneasy compromise, this Halfway Covenant lasted into the eighteenth century. Puritans and Catholics defined their bodies of communicants differently, with Puritans taking pride in their more restrictive Lord’s Supper.

Debating Communion and Cannibalism

Like the cup itself, the wine within held complex meanings for Puritans, who rejected the Catholic belief in transubstantiation. The most important division between the two religions was the question of what communicants ingested during the communion service—blood or wine, flesh or wafer. The resulting arguments—miracle versus metaphor—played out over and over again in Catholic and Protestant writing and practice.

The Catholic doctrine of the miracle of transubstantiation relied upon a literal interpretation of Jesus’s words in 1 Corinthians 24-25: “This is my body … This cup is the new testament in my blood.” A priest’s blessing transformed sacramental wafers and wine into Jesus’s actual flesh and blood. According to the Douay catechism, the Eucharist was “the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ … under the forms or appearances of Bread and Wine.” John Gother, an English convert to Catholicism, placed belief in transubstantiation at the forefront of Catholic faith. “My Saviour Jesus Christ,” he wrote, “I firmly believe Thou art really present in the Blessed Sacrament; I believe that it contains thy Body and Blood, accompanied with thy Soul and Divinity.”

Protestants disagreed, insisting that Christ’s words should be interpreted only as a metaphor. The Westminster catechism specified that communicants partook of Christ’s flesh and blood “not after a corporal and carnal manner, but by faith” alone. Nevertheless, Puritan devotional writings contained a hunger for communion that seemed to transcend figures of speech. Cotton Mather expounded upon the life-sustaining qualities of bread and wine, declaring that Christ’s love similarly fed the soul: “If Bread nourish & strengthen the Body, much more will the Lord Jesus do so, to the Souls of them, who draw near unto Him,” he wrote. Though Protestants were not consuming actual flesh and blood, Mather argued that a true believer would nevertheless be able to “Discern the Lords Body in the Lords Supper.” But the importance of the Lord’s Supper went beyond discerning the holy in the seemingly mundane. Communion satisfied a particular kind of spiritual appetite. Another Puritan minister, Thomas Doolittle, asked of communicants, “Do you love him, would you not desire to eat and drink at his Table, yea, to feast upon him? … Did you hunger after him, and thirst for him …?”

Edward Taylor certainly did. The Westfield, Massachusetts, minister wrote reams of devotional poetry, including several “Meditations” on John 6:53, “Except you eat the flesh of the Son of Man, and drink his blood, ye have no Life in you.” Unlike Mather, Taylor did not belabor the distinction between wine and blood. He described the Lord’s Supper in literal, visceral terms: “Thou, Lord, Envit’st me thus to eat thy Flesh / And drinke thy blood more Spiritfull than wine.” Communion provided a special kind of nourishment that secular food could not, nourishment without which believers would starve: “I must eate or be a witherd stem,” Taylor declared.

In spite of hungers like Taylor’s, most Puritans interpreted transubstantiation as no less than lust for human flesh. The idea that Catholics consumed Christ’s real body and blood made them “so much worse than Canabals,” Mather declared. Taylor therefore recognized the tricky balance he had to strike, between venerating the body of Christ, and being a metaphorically minded Puritan. One of his meditations posed these very questions about communion: “What feed on Humane Flesh and Blood? Strang mess! / Nature exclaims. What Barbarousness is here?” Like a good Protestant, Taylor answered himself by arguing that Christ’s words were symbolic: “This Sense of this blesst Phrase is nonsense thus. / Some other Sense makes this a metaphor.”

Spilling Blood

The consequences of the debates between miracle and metaphor would be literally bloody, leading to centuries of religious warfare after the Reformation, in the Old World and the New. As New England’s Puritans defined their own beliefs and communities, they did so with an anxious eye toward the French Catholics in Canada just to their north. Between 1690 and 1763, New France and New England were at war more often than at peace.

The intimate act of communion incorporated the body of Christ into one’s own. Those Puritans who drank from the silver cup hungered after communion, a hunger that in many ways resembled the Catholic hunger for the host in the mass, though Puritans were loath to admit it. The body of the communion cup helped to bridge the space between the believer and God, but it also divided believers from one another. Puritans and Catholics drew the boundaries of their communities in blood, then went out to draw the blood of their enemies.

Further Reading

For more on New England communion silver, see New England Silver and Silversmithing 1620-1815, edited by Jeannine Falino and Gerald W.R. Ward (2001); and Barbara McLean Ward, “‘In a Feasting Posture’: Communion Vessels and Community Values in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century New England,” Winterthur Portfolio 23:1 (Spring, 1988): 1-24. Observers rarely described Puritan worship services in detail, but much of what historians know about them is summarized in Philip D. Zimmerman, “The Lord’s Supper in Early New England: The Setting and the Service,” New England Meeting House and Church: 1630-1850, Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings 1979, edited by Peter Benes (1979): 124-134. On Puritan beliefs and practice, important works include David D. Hall, Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (1989); Charles E. Hambrick-Stowe, The Practice of Piety: Puritan Devotional Disciplines in Seventeenth-Century New England (1982); and Sally Promey, “Seeing the Self ‘In Frame’: Early New England Material Practice and Puritan Piety,” Material Religion 1:1 (2005): 10-46.

On Protestant-Catholic conflict and accusations of cannibalism, see Catalin Avramescu, An Intellectual History of Cannibalism, translated by Alistair Ian Blyth (2009); Karen Gordon-Grube, “Evidence of Medicinal Cannibalism in Puritan New England: ‘Mummy’ and Related Remedies in Edward Taylor’s ‘Dispensatory’,” Early American Literature 28:3 (1993): 185-221; Maggie Kilgour, From Communion to Cannibalism: An Anatomy of Metaphors of Incorporation (1990); and Richard Sugg, Mummies, Cannibals, and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians (2011). On religious conflict and convergence in early New England and New France, see Laura M. Chmielewski, The Spice of Popery: Converging Christianities on an Early American Frontier (2011); and Linford Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America (2012).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3 (Summer, 2016).

Carla Cevasco is a doctoral candidate in the Program in American Studies at Harvard University. She is writing a history of hunger in colonial New England and New France.