Sponsored by the Chipstone Foundation

Busts are odd things. Heads free of their bodies, severed at the shoulders, often at the neck, and plopped on architectural bases. They emerge from the sides of buildings, arise from monuments, line libraries, occupy museums, attend grave markers, and greet us from dreary governmental buildings. Busts are, in essence, decapitated heads. And perhaps, in that sense, it isn’t a surprise that the Romans were the first to pioneer the form, as they slashed their way across the Mediterranean world. Most cultures have fixated on the head in their efforts to represent people. After all, the head is where we do our thinking, speaking, listening, and where our emotions reveal themselves—the whole self in a small compass, as it were. But there is always a whiff of destruction in the desire to capture the body in stony substance. The body is not above decay, but in order to set it in stone, humans must cut, chisel, smother, cast, even fire—enact a series of small deaths to represent the body in perpetuity.

At the center of Protestant devotion to eminent divines is mimesis—an urge to be cast in the mold of their preeminent saint.

Despite the ambivalence, sometimes verging on antagonism, among Protestants towards the sacred image, this essay tracks a fixation on the severed head of a prominent Protestant divine, even saint: John Wesley, the preeminent founder and leader of the evangelical movement known as Methodism (fig. 1). Wesley’s head was not chiseled out of fine marble, but almost exclusively cast in pottery. Efforts to capture Wesley’s body and possess a part of his “true nature” participated in a mid- to late-eighteenth-century obsession with highly realistic portraiture, in sculpture as much as painting. But instead of a block of stone from whence a head emerged, a modeled clay depiction of the holy man from “life” was made into a mold and mass-produced in a dizzying array of pottery forms across the Atlantic world. These countless molds were filled and fired with the clay of the small landlocked county of Staffordshire, England. In so doing, Wesley’s presence was transferred in ways that transcended his printed words and transferred not only his bodily image, but the actual land and labor of an area of England that held him in special regard.

At the center of Protestant devotion to eminent divines is mimesis—an urge to be cast in the mold of their preeminent saint. But it would be eighteenth-century Staffordshire potters who would do this work first. Through their massive production they were able to assert their “great man” as a means of connecting a rapidly expanding but scattered Methodist tradition, and as a means of applying the firm pressure of the past upon their tumultuous present.

Objects are prone to legend. They have a tendency to accrue more myth than history, and more hearsay than labels. The material culture of this Protestant saint is no exception. In an unknown location in England, at an unknown time, an artist, Mr. Culy, invited a friend over for evening tea. After initial pleasantries, the two were soon circumnavigating the artists’ home gallery of portrait busts. One bust stood out to his visitor. Who is this, the friend asked? Why, it is a bust of the “Rev. John Wesley,” the artist replied. His visitor was enamored, and he was not alone. Culy told his visitor that it “struck Lord Shelburne in the same manner as it does you.” But when Lord Shelburne learned that it was John Wesley, he was aghast: “He—that race of fanatics!” Culy had assured Shelburne that Wesley was a very humble man, and had always refused to have his likeness taken, thinking it “nothing but vanity.” But after offering Wesley “10 Guineas” for every ten minutes he would sit for him—”knowing you value money for the means of doing good”—Wesley amazingly assented. So Wesley removed his coat, lay on the couch, and the artist prepared the plaster, and laid the wet, cold substance on Wesley’s bare face. After eight minutes, Culy “had the most perfect bust” he had “ever taken.” Wesley washed his face, “counted the ten guineas in his hand,” and said, “I never till now earned money so speedily—but what shall we do with it?” For Wesley, it turns out, this wasn’t hard. On the way home he encountered the suffering dregs of British society: “a poor woman crying bitterly,” “a poor wretch who was greedily eating some potato skins,” a “man, or rather a skeleton,” a “young woman in the last stage of consumption,” an “infant, quite dead,” and a heavily indebted lawyer. Soon Wesley’s 10 guineas were consumed in his efforts to alleviate this deluge of suffering. After hearing this story, Lord Shelburne’s heart was softened against the leader of the “race of fanatics,” and in response, he “immediately ordered a dozen of the busts to embellish the grounds of his beautiful residence.” Shelburne’s transformation, from indignation to devotion, was a powerful story of how the bodily representation of John Wesley could overcome anti-evangelical prejudice and transform it to devotion, all with the help of a story attached to a thing.

This legend about the origin story of John Wesley’s bust and its power was reprinted widely in America in nineteenth-century religious and secular periodicals. One reason for the dissemination of the story was the growing presence of John Wesley, not only in prints that could be tacked to walls, or on copper engravings printed in the frontispiece of books, or on the name of institutions, but in the growing ubiquity of his representation in pottery form. “Wesleyana” flooded middling and lower domestic spaces across the British Isles and North America from the late eighteenth century on. This has led some experts to claim, perhaps in a moment of exaggeration, that Wesley was the most represented British person in ceramics in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, probably only surpassed by Queen Victoria. Another reason for the popularity of the story was a desire that the prized busts of Wesley were directly related to his actual face, an indexical portrait that circumvented the mediation of an artist. It wasn’t simply an image of Wesley, open to exaggeration or enhancement. Through the direct contact of plaster on his living face, it wasWesley, more than any other image of the man. This alleviated a lingering Protestant unease with the sacred image, by promising a representation “from nature,” of which God was the undisputed artist.

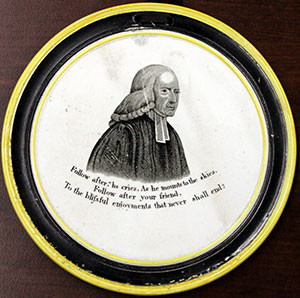

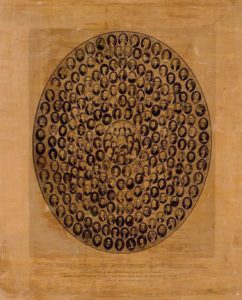

Wesley appeared not only in busts, but also on plates, teapots, clocks, medallions, intaglio presses, door knockers, wax profiles, walking sticks and figurines (fig. 2). Nearly all of this pottery came from Staffordshire. These objects were like action figures in a period when Methodism was exhibiting its otherworldly strength. In America, this strength was on full display. On the eve of the Declaration of Independence, there were only 69 Methodist congregations in the American Colonies. By 1850, there were almost 200,000. Whereas in the eighteenth century Methodists trailed nearly every other sect, by the Civil War they claimed a third of American church members (church attendance was even higher). This led President Ulysses S. Grant to quip in 1868 that “there were three great parties in the United States: The Republican, the Democratic, and the Methodist Church.” This expansive growth, forged on reaches of the Atlantic world, has led one prominent historian to call Methodism an “empire of the Spirit.” In Methodism’s rapidly expanding solar system, John Wesley was its burning sun (fig. 3). Wesley chose the songs that Methodists sang; he selected (and mercilessly edited) the books Methodists read; he dictated Methodist religious practices; he expressed their first ethical positions; he set their theological doctrines; he established their organizational structure—he was the movement’s most powerful religious force.

Staffordshire potteries were clustered in the small towns of Burslem, Tunstall, Stoke, Hanley, Longton, and Fenton (fig. 4). These pottery factories maintained a stranglehold on the middling Atlantic pottery market from the late eighteenth century on. Most of the firms persist to this day—familiar names such as Wedgwood, Minton, and Spode—and enjoy avid collecting communities. The five major pottery towns were landlocked, but they laid beside a turnpike that led to the ports in Liverpool. The completion of the Trent and Mersey Canal in 1771 gave the potteries port access to the world, and this accelerated north Staffordshire’s already well-established pottery industry. They had a near-perfect situation for Atlantic dominance. The towns’ historic reputation for pottery drew skilled artisans from across England. Coal and clay were abundant in the rolling hills, often at the very same sites. Transportation became easier and cheaper by the year. Many shrewd businessmen led the pottery firms, combining a razor-sharp sensitivity to shifts in “taste,” along with a tendency to embrace mechanical and scientific innovation. Living in the intimidating shadow of Chinese porcelain, Staffordshire potters discovered new methods of expression—from glossy glazes to colored enamels, and from elegant white creamwares to dark, durable redwares. The resulting products varied widely as well, from whimsical “toby jugs” to classical sculptures, from jasperware (a colored, mock porcelain) totransfer prints (a method of transferring inky text and design onto fired clay). By the nineteenth century, most middling Americans enjoyed their dinners and took their tea from ceramics made from the clay, thrown by the potters, and fired from the coal of Staffordshire.

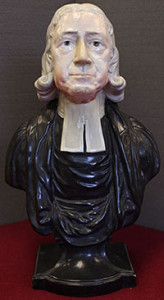

John Wesley first came to the North Staffordshire town of Burslem in March of 1760, and he described it as a “scattered town on top of a hill, inhabited almost entirely by potters.” Methodism thrived in Staffordshire. Wesley stopped there annually, in his wide circuit of Methodist societies and chapels. Looking backward in 1784, he called Burslem “the first [Methodist] society in the country, and it is still the largest and the most in earnest.” In the years after Wesley began visiting Staffordshire regularly, the potters had begun to make portrait medallions of the great leader, a representational tradition that would be greatly expanded and perfected by Josiah Wedgwood (fig. 5). These small likenesses of the preacher were often given as gifts, from one Methodist to another. This practice inaugurated a long tradition of giving little Wesleys to establish bonds between Methodists near and far. This appears to be the way the first potted Wesleys made their way to American shores—gifts from traveling Staffordshire potters on business trips to their American sisters and brothers. Over this particular body, bonds could be made. The other means of American collecting was pilgrimage. As many prominent American Methodists traveled to their English holy land, they often brought Wesley relics back with them—pressed flowers from his childhood home, personal relics, like his glasses, or the velvet from his chair, and most commonly, pottery. They were souvenirs, for sure, but it was often more—a desire to possess the material of a very particular, venerated life. The busts thus often earned the title of “relic,” not only for being old, but also for their purported “exact representation” of the elderly religious leader. This was not simply a “likeness” of Wesley, but somehow carried a part of him. The legend of “Mr. Culy” making a bust from a life-mask became too enticing to deny. Despite the legendary tale with which this essay opened, it was not “Mr. Culy,” but rather Enoch Wood, who would sculpt with his fingers—rather than a life mask—the standard Wesley bust in 1781.

Enoch Wood grew up among the distinctive bottle kilns of Burslem, in a potter’s family that specialized in modeled figurines. Young Enoch demonstrated considerable talent, using spare pieces of abandoned clay to try his hand at sculpting. When Enoch was fourteen, some traveling artists came to town, with a box in tow. Beneath the mahogany encasing and a velvet lining was a wax crucifix. Wood watched his fellow townspeoples’ astonishment in seeing the crucifix, “how it seemed to soften their hearts and open their purses.” He knew he could do better. So he endeavored to make a bigger, better crucifix, hoping to take it on the road, and with his earnings, see the world. Four years later, he amazed his fellow potters with an even more impressive production of a three dimensional, basso relief of John David Rubens’ Descent from the Cross, made in the famous blue and white of jasperware. It is unclear if these early artistic efforts helped Enoch see the world (he at least made it to Liverpool to study art and anatomy), but his pottery would travel far. And he never forgot the lesson of marshalling his talent for economic gain. He became a master potter in his early twenties and led a long career of pottery production that specialized in ceramic products for the American market. If Josiah Wedgwood was the recognized “prince” of the Staffordshire potteries, Enoch Wood, by the end of his life, would be remembered as their “father.”

In 1781, at the age of twenty-two, Enoch Wood had the sculpting opportunity of his lifetime. Through a fellow potter, he arranged to “take” Wesley’s head. In five separate sittings, Wood used modeling clay to sculpt the holy man as he was hunched over, catching up on correspondence. Enoch’s wife, Ann, tried to help, attempting to divert Mr. Wesley with some polite conversation. But she couldn’t get him to look up from his letters for long. As a result, Enoch’s sculpture “from life” was a bit too accurate. Wesley was impressed, saying it was the best likeness that had ever been taken of him, but Wood had copied the concentration on his brow with a bit too much fidelity. He looked stern and harsh. And Wood had embarrassed Wesley’s manservant by copying his rumpled clerical gowns, which had been crushed in his travel bags. So Wesley sat back down for a few minutes, and Wood gave him a lift (though his clothes would remain crushed in the early editions of the bust) (fig. 6). Wesley was pleased and told Wood not to touch it, lest he “mar” it. Wood had a tradition of placing small medallions on the rear of his busts that gave the name, age of the sitter, and an additional note about the person’s life—”any remarkable occurrence.” Without the “smallest hesitation,” Wesley told Wood his remarkable moment. For Wesley it was the story of being saved from the flames of his family home in Epworth as a child, and that Wood should write on the medallion, “Is not this a brand plucked from the fire.”