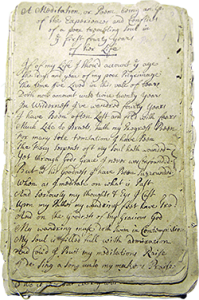

Since the volume of extracts noted that the original “small leather covered book” remained in family hands in 1895, I reasoned that, another hundred years later, it might still be held by Mehetabel’s heirs. I began compiling a Coit genealogy to try to identify possible lines of descent. At the same time I contacted a number of museums and libraries to ask whether the diary might be in their collections, early on making the fortunate decision to get in touch with Yale University. Although Yale did not have the diary, it did own the two letters that had appeared in the volume of extracts, along with a treasure trove of more than twenty letters written between 1688 and 1743 by Mehetabel’s mother, Elizabeth Douglas Chandler (1641-1705); sister, Sarah Chandler Coit Gardiner (1676-1711); daughter, Martha Coit Hubbard Greene (1706-1784); mother-in-law, Martha Harris Coit (1642?-1713); and friend, Elisabeth Bradstreet Slaughter Wass Adams (b. 1694). (A selection of Martha Greene’s letters and one by Elisabeth Adams were featured in a second volume published by the family editors in 1895, Martha, Daughter of Mehetabel Chandler Coit, 1706-1784, but had not appeared in print since.) This extraordinary collection of early women’s writings contained a degree of detail that greatly enhanced my understanding of Mehetabel’s experiences, as well as offering insights into numerous aspects of early American life (fig. 1).

Yale’s records noted that the letters had been donated over a period of time beginning in the 1940s by Elizabeth L. Anderson (née Gilman) of New York. They also indicated that Elizabeth Anderson was the owner of Mehetabel’s diary (although they misattributed it to Mehetabel’s daughter Martha). Since Yale’s records stated that Elizabeth Anderson had died in 1950, I turned my attention to looking for her obituary so as to learn the names of her heirs and possibly identify the current owners of the diary. Although I came across a 1950 obituary for Elizabeth’s cousin, Baltimore political activist Elisabeth Gilman, I was unable to locate any death record for Elizabeth Gilman Anderson. By this time I had determined where she fit on the Coit family tree—she was the great-granddaughter of the diary volume editors’ brother, Edward Gilman—so I decided to check her parents’ obituaries for possible leads. Since her father, Lawrence Gilman, a well-known music critic, had died in 1939, his obituary was not particularly helpful, but the 1964 death notice for her mother, Elizabeth Wright Walter Gilman, contained the revelation that Elizabeth Gilman Anderson was still living at that time. Evidently, Yale had misidentified Elisabeth Gilman of Baltimore as the donor of the manuscripts in its collection.

The obituary noted that Elizabeth lived in a small town in upstate New York. On a whim, I decided to call the town assessor’s office to ask how I might find out when Elizabeth’s house had sold, figuring that this information could bring me closer to her real date of death. Incredibly, the clerk in the assessor’s office was able to tell me right away that the home had sold in the 1980s; she was also able to provide the name and phone number of the buyer, a local realtor who happened to have been a friend of Elizabeth’s. I then called the buyer, who told me that Elizabeth had moved to Pennsylvania and that he had maintained contact with her until about four years previously. He suggested I speak with his wife, who might know more. Although his wife hadn’t heard from Elizabeth in a while, she put me in touch with Elizabeth’s former handyman, who in turn offered the reassuring report that her cemetery plot remained unfilled. He also supplied me with the name and number of Elizabeth’s former housekeeper. The housekeeper had communicated with Elizabeth as recently as a year before, and she was able to confirm the name of the Pennsylvania assisted-living facility where Elizabeth had become a resident. I immediately called the facility and was informed, much to my delight, that Elizabeth, at ninety-five, was alive and well.

Since Elizabeth’s hearing was impaired, the social worker at the facility suggested I write her a letter rather than trying to speak with her on the phone. My first impulse was to jump on a plane and go see her, but I was ultimately glad I heeded the social worker’s advice. Elizabeth ended up being not quite sure what she had done with the diary and believed she might have donated it to Yale along with the other family papers. This was a discouraging development, but events took a turn for the better when the social worker put me in contact with Elizabeth’s closest relative, a cousin living on Long Island. I phoned the cousin’s home, explained to his wife why I was calling—and received the wonderful news that the diary was in their possession!

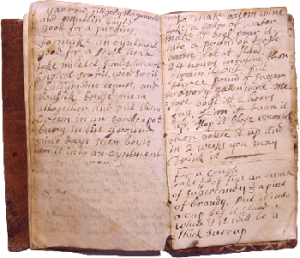

The couple soon sent me a copy of the fifty-page manuscript, which I was thrilled to discover contained an amazing assortment of material not included in the published extracts. Interspersed among the entries were poems (“for the few Hours of Life/Alotted me/Grant me great god/but bread and liberty”); recipes (“to make ba[l]som wine”); herbal and folk remedies (“powder of earthworms will make an Akeing tooth fall fall [sic] out of itt selfe”); financial accounts (Hannah mannorwing to [1?] yd of Scotch Cloath att 0 – 5 – 0 [?] to a quart of Rum”); religious meditations (“the patience of god to [sic] towards sinners is the greatest miracle in the world”); and even some humor (“Deliverd in a Dull and lifeles strain, the best Discorses, no attention gain, for if the orater be half a sleep, he[‘]ll scarce his auditors from snoring keep”). These features add immeasurably to the diary’s larger historical significance as well as to the telling of Mehetabel’s individual story (fig. 2).

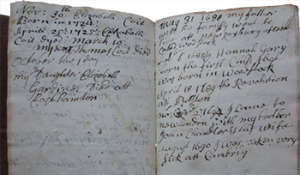

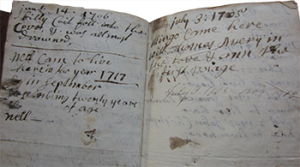

Another way the diary differed from the volume of extracts was that its entries did not appear chronologically but were organized thematically in many cases, with some pages carrying entries relating to Mehetabel’s or her family’s journeys, for example, and others chronicling the births of her children or the launchings of her husband’s ships. The specificity of the entry dates point to their first being recorded at or near the time of the actual event (“febbr 6 1688/9 Hannah Gary born the first Child that was born in Woodstock”; “may 2 1696 Wait Mayhew came to live here”). However, I took the diary’s inscription, “Mehetabel Coit Her Book 1714,” to mean that Mehetabel acquired this particular journal in 1714 and then copied into it entries from an earlier notebook or collection of scraps of paper (fig. 3).