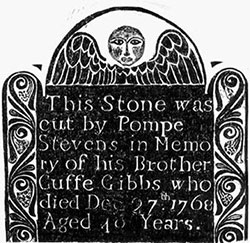

At Christmastime in 1768, a slave named Cuffe Gibbs died in Newport, Rhode Island. He was buried in the Newport Common Burying Ground beneath an inconspicuous gravestone carved from dingy, low-quality slate (figs. 1, 1a). A casual visitor might never notice his monument, which is ordinary in size, shape, and iconography. It is competently executed, but notable only as a sturdy example of the conventions of New England stone carving from the middle of the eighteenth century.

And yet, it is a treasure. Or, rather, the key to a trove of treasures. Alongside the ordinary iconography, the carver etched an extraordinary epitaph:

This Stone was

cut by Pompe

Stevens in Memo

ry of his brother

Cuffe Gibbs, who

died Decr. 27th. 1768,

Aged 40 Years.

Pompe Stevens and Cuffe Gibbs were slaves, as were over a thousand other Newporters on the eve of the American Revolution. They were also brothers, a relationship obscured by paper documents, but preserved by Pompe Stevens’s own hand. As a trained stone carver, Stevens was able to create an enduring monument to his brother and to himself. By emblazoning his own name across his brother’s epitaph, Pompe Stevens claimed both his family and his craft. Stevens’s work was a challenge to his contemporaries, prodding them to acknowledge black families that existed in fact, if not in law. It is no less a challenge to modern scholars, collectors, and curators. At a time when museums and other cultural institutions are devoting tremendous resources to making their collections more inclusive, Pompe Stevens’s work offers a valuable starting point for reimagining early American decorative arts. Surviving objects like silver, furniture, and gravestones were rarely the work of lone geniuses working in isolation. Rather, they were commercial goods made in workshops where artisans and laborers with varying degrees of skill and freedom worked side by side. In every colony, from New Hampshire to Georgia, some of these skilled craftsmen were slaves. This historical reality complicates narratives that link artisanship with independence and juxtapose the purported modernity of Northern cities with the supposed backwardness of slavery. But it also provides a tremendous opportunity to collectors and curators willing to look at early American decorative arts with fresh eyes.

Any signed work by an African American artisan from the colonial era is a rare object. Skilled slaves, North and South, worked in nearly every craft, from building houses to stitching silk dresses, but the fruits of their labor are often unmarked or uncritically attributed to their masters. Some sculptures and ornaments have been recovered archaeologically at sites like the African Burial Ground in Manhattan, but scholars, museums, and private collectors hoping to tell the history of African American art have struggled to identify works by nameable artists that predate the Civil War. The few signed works that do exist have become highly coveted pieces. Heavy, earthenware jars inscribed with short poems by potter Dave Drake (c.1801-c.1870s) of Edgefield, South Carolina, sell for tens of thousands of dollars at auction and are exhibited in major art museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Furniture made by the free North Carolinian joiner Thomas Day (c.1801-c.1861) and vessels by free New York potter Thomas Commeraw (active c.1796-c.1819) are similarly sought after. These pieces are often classified as “folk art” or “rural art” and exhibited separately from “fine art” furniture and tableware.

The acquisition of pieces like Dave Drake’s jars is a good step toward diversifying museum collections. But, in searching out previously unknown works, American art museums overlook a rich, untapped reserve of slave-made objects: their own collections of decorative arts.

The Cuffe Gibbs stone provides a useful lesson in recontextualizing Euro-American crafts as slave-made objects. As a conventional gravestone, formally indistinguishable from a thousand of its neighbors, the monument is hidden in plain sight. Without Pompe Stevens’s explicit claim of authorship, gravestone scholars would have few qualms about numbering Cuffe Gibbs’s stone among the works of Pompe’s owner, William Stevens. Some might note the slightly erratic alignment of the letters, but the stone’s commonplace border and conventional winged effigy are utterly ordinary. Unsigned, it is just another product of William Stevens’s workshop.

How many other slave-made objects survive, overlooked, in our museums and private collections? If slaves worked as skilled stonecutters and silversmiths, joiners and engravers, pewterers and jewelers, surely they made spoons, chairs, woodcuts, plates, and rings. A close look at Pompe Stevens’s signed work can reveal a great deal about his training and the probable extent of his unsigned work. The implications for other decorative arts are clear. If Pompe Stevens’s work is included in the larger body of work attributed to his master, the same is probably true of objects made by slaves trained in other Euro-American crafts.

Little is known about Pompe Stevens’s life other than what can be inferred from his work. Given the long odds against families surviving the Middle Passage intact, he and his brother were probably born in Newport. Whether they arrived in Newport by ship or by birth, Pompe and Cuffe were separated at some point. Their different surnames derive from the paternalistic idea that slaves were junior members of their masters’ households, not heads or members of their own families. Other gravestones in the Newport Common Burying Ground testify to the rhetorical impossibility of black families by memorializing “Flora Coggeshall, wife of Mark Tillinghast” or “Pompe Rogers Son of Prince Sanford.” Stevens’s young son, Princ[e], is buried next to Cuffe Gibbs, under an epitaph identifying him as the “Son of Pompe Stevens and Silva Gould.” When he named their fraternal relationship on Cuffe Gibbs’s gravestone, Pompe Stevens exposed the lie in their names. It is the only gravestone among thousands in the burying ground that defines an adult black man in terms of his relationship to a relative, rather than an owner.

![2. "In Memory of Pompey [Lyndon] (a beloved Servant of Jonas Lyndon) who died Sept. 11, 1765. Aged 28 Mo. and 19 Days." Initialed as cut by P.S. Newport, Rhode Island, 1765. Rubbing by Sue Kelly and Anne Williams (photo No. 2087). Courtesy of the Farber Gravestone Collection, the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](http://commonplace.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/02-1-192x300.jpg)