On the road to the halftone revolution

When William James Linton left England in 1866, bound for a new life in New York City, he was what we would now call middle aged, with more than three decades of a career as a wood engraver already behind him. Linton’s reasons for leaving England were complicated, but somewhere in the mix must have been his disappointment with the state of wood engraving as it had come to be practiced in London. Developed as a distinctive technique late in the eighteenth century, wood engraving had always been used almost exclusively for commercial purposes, to illustrate books and periodicals. But for Linton wood engraving was also an art, in the sense that it was a means for expressing the most essential truths about nature and beauty. When Linton learned the craft in the 1820s it was easier to dwell on its artistic possibilities, since the demand for illustrations was relatively low. That changed, though, in the 1840s, when periodicals like the Illustrated London News created an almost insatiable demand for wood-engraved illustrations. As engravers crowded in to meet that demand, they formed large engraving firms and devised clever new ways of dividing up labor in order to speed production. Linton deplored this industrialization of the craft, and he later wrote that by the time he left England, “there was no art of wood-engraving.”

The United States turned out to be a hospitable place for Linton to start anew. Shortly after arriving in New York he accepted a position teaching wood engraving at the Cooper Union; he was hired to work in the art department of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (which employed the same labor-divided methods Linton left in England—he didn’t last long there); and he was soon busy as a freelance engraver, with work coming in for both book and periodical illustrations. By 1870 he was established enough to leave New York for the quieter setting of Hamden, Connecticut, where he moved into a small house he called “Appledore” and continued his prospering career as a freelancer.

This was an especially exciting time for Linton and anyone else hoping to see wood engraving rise (or return) to the level of art in the sense that Linton had in mind. In the years since the end of the Civil War, publishers in the United States had founded a handful of illustrated periodicals—including the Aldine and Appleton’s Journal—that gave far greater attention to the aesthetic possibilities of wood engraving than did the wildly popular Frank Leslie’s and Harper’s Weekly. Few of these periodicals would survive for more than a decade, but they proved to be a boon for freelance engravers, who tended to be more artistically inclined—or at any rate more free to pursue their artistic inclinations—than those working for engraving firms or in house for magazines. They also set a new standard for the “white line” style of engraving that Linton and others agreed was where the distinctive art of wood engraving was to be found. Linton engraved for virtually every one of these periodicals, and by the early 1870s he had become something of an icon among American wood engravers.

It was with great concern, then, that Linton—probably late in 1878—noticed a “new phenomenon” in wood engraving that was pushing the form in a different and to his mind grievously wrong direction. In recent issues of Scribner’s Monthly Magazine, one of the newer (though by now well-established) illustrated monthlies, Linton saw that some of the illustrations—all wood engravings—sought to mimic the tones and textures of the drawings or paintings on which they were based, departing radically from the white-line style he believed was essential to good engraving. Linton knew that many of these engravings were made from images that had been photographically transferred rather than drawn onto the woodblock, a relatively new practice that seemed to him to be a further denigration of the craft.

By early 1879 he had seen enough to write an article on the subject, which the Atlantic Monthly published in June under the title “Art in Engraving on Wood.” Long, tendentious, and occasionally nasty (at one point Linton recalls his “disgust” upon viewing the work of the one engraver he criticizes by name, Timothy Cole), Linton’s article was in fact a diatribe, and it settled on one main complaint about what was already being called the “new school” of wood engraving. To be an art, Linton argued, wood engraving needed to be more than merely reproductive, something that Cole and others seemed not to understand. Rather than “translate” a picture from another medium to the distinctive lines of wood engraving, these engravers sought only to duplicate the original picture—a painting or a crayon drawing or even a photograph taken “from nature”—down to the last detail, so that the print from the engraving looked as much like the original as possible. For Linton this was a return to mere “facsimile” engraving, where the chief concern was a literal fidelity to the original picture. An engraving, he implored, ought to be something altogether new, “not a photographic image of the picture, but an engraving.”

Linton’s interests were not as rarified in 1879 as they would be today. In fact, through virtually all of the nineteenth century, wood engraving was probably the most common means for bringing pictures before the public. Turn the pages of any illustrated book, pamphlet, or periodical published before 1885, and it is fairly certain that most of the illustrations are wood engravings. There were lots of other ways of printing pictures, of course, and as the century progressed the range of possibilities grew, as inventors and tinkerers developed a whole host of marvelous new graphic technologies, including the most marvelous of them all, photography. Wood engravings remained the overwhelming preference for illustration, though, mostly because they are printed in relief, like raised type, making it possible to print them alongside text. This was not yet true for photographs, which required their own tools and techniques to be printed from negatives.

But wood engravings were costly and time-consuming to make, and the advent of photography made them seem in some instances to place too many layers of mediation between the picture and the thing depicted. Those wanting to address these deficiencies were soon at work on a way to produce relief blocks using some kind of photographic process that would eliminate the costly and intermediary engraver. By the 1870s a method for “photo-engraving” line drawings had been developed, but it was not until the 1880s that a good method was devised for photoengraving tonal images like photographs. It was this “halftone” process that spelled the end of commercial wood engraving, for now any picture, including a photograph, could be printed in relief without the need for an engraver. Turn the pages of any illustrated book or periodical published after 1895, and it is fairly certain that most of the illustrations are halftones or line-blocks.

For Linton, the “photographic” style of the new school was pointing the direction and paving the way to this unfortunate end. But he wrote in the midst of developments he neither understood nor could fully predict, and while there was prescience in his article, there was also a good deal of irony. It is true that photography and wood engraving converged in the new school, not only visually (in the way the engravings looked) and conceptually (in the reproductive fidelity new-school engravers strove for), but also technically, in that photography was now being used as a tool in the production of wood engravings. The intersection of these two means for making pictures was not as dire to the artistic fortunes of wood engraving as Linton feared, however. Indeed, as photography and wood engraving traveled together in the field of illustration through the 1880s, wood engraving came to be valued as a fine art in ways that Linton could never have imagined a decade earlier. And when museums and connoisseurs began to collect wood-engraved prints, it was the reproductive work of the new school they sought, not the white-line engravings of the 1860s and 1870s. The story of photography and wood engraving in the nineteenth century, then, is not simply a story of one technology’s ascent and the other’s decline. Photographs did eventually replace wood engravings in illustration, but before that photography joined and transformed wood engraving so as to favor its claims as a fine art.

Crucial to the rise of wood engraving as a commercial art were the technique and style of engraving popularized in the late eighteenth century by the Englishman Thomas Bewick, one of the art form’s most celebrated practitioners. Bewick used a tool for engraving on metal called a graver to cut across the grain of a very hard wood (boxwood), and he produced his images using arrangements of white lines—the lines cut by the graver—instead of the black lines one typically sees in drawing and intaglio engraving. The technique was what distinguished wood engraving from wood “cutting,” and the style—called white-line engraving—stood in contrast to what was called facsimile (or sometimes black-line) engraving, where the engraver simply cut away the wood on either side of the lines drawn by the artist. An engraving titled Sage-Hen and Jackass-Rabbit, also engraved by Davis after a drawing by Beard and published in Scribner’s in 1877, shows both facsimile engraving—in the sky and in the hillside and plants on the left—and white-line engraving, through most of the rest of the hillside and in the rabbit in the foreground (fig. 1). Another illustration from the same article, also engraved by Davis after a drawing by Beard, shows a more fully developed white-line style, where virtually the entire image was produced by arranging white lines of different widths and lengths, as a detail makes clear (fig. 2).

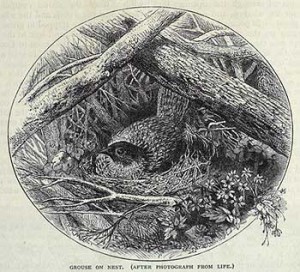

From its inception, photography could contribute a great deal to the creation of wood engravings such as this. Photographs could, most simply, serve as sources for illustrations, so that the artist who drew the image onto the woodblock could work from something other than a drawing or memory or the imagination. This was especially appealing for illustrations that needed to be appreciated for their accuracy, such as a portrait or any other picture that promised to deliver more information with closer scrutiny. By the 1850s it was not unusual to see wood-engraved illustrations cited as being “from” or “after” a photograph—such as one titled Grouse on Nest from the same Scribner’s article as the Davis engravings—claiming something of the veracity of photography even if the illustrations themselves really looked nothing like photographs (fig. 3).

That same decade saw the development of a new and much more direct use of photography in wood engraving. In a technique sometimes called “photoxylography,” whatever picture was to be engraved could be photographically printed directly onto the woodblock, freeing up artists to work in whatever medium they wished and removing the need for an intervening draughtsman. It was this practice, which the art editor of Scribner’s was making regular use of by the mid-1870s, that helped give rise to the reproductive logic of the new school. Timothy Cole’s The Gillie-Boy, which appeared in Scribner’s directly across from Grouse on Nest, is generally considered the first wood engraving to apply this new logic (fig. 4). Cole later wrote that James Kelly, the artist who painted the original picture, had asked the art editor to “insist that his manipulation throughout, . . . be suggested, or carried out in fact, by the engraver.” Cole took these instructions to heart, and the result was “the first instance of the new manner.” The most dramatic departure from conventional engraving is through the sky and along the periphery of the image, where Cole attempted to reproduce the look of Kelly’s brush strokes. Partly what made this “new manner” more photographic than white-line engraving, then, was the technical reliance on photography to produce the engravings.

But for Cole and other new-school engravers, photography offered not only a technical means for preparing their woodblocks for engraving but an entirely new way of conceiving their work. This new understanding had them much more likely to use the word “reproduce” than “translate” or “interpret” (the words favored by Linton) to describe their work as wood engravers. As one member of the new school put it, the “business” of the wood engraver “is to reproduce a picture as well as the looking-glass does.” This shift to a reproductive mode signaled as well a shift in thinking about “fidelity” in art. For Linton, the fidelity of the engraver was to the essential meaning of the work to be engraved, and it was this essential meaning that the engraver needed to maintain when translating the work into white and black lines. For new-school engravers like Frederick Juengling, the fidelity of the wood engraver was simply to the picture itself, precisely as it looked. “What it seeks,” he wrote of the new school, “is a perfect reproduction of the original.” Admirers frequently insisted that a kind of self-effacement on the part of the engraver was crucial to attaining this reproductive fidelity. They argued that a wood engraving should be free from any personal style and as free as possible from the formal demands of the medium, so that (in the words of one engraver) “the spectator will see in the engraving, not the engraver, but the original artist.” Linton derided this ideal of transparency as a “new acquirement of self-abnegation,” but to his critics he was simply more devoted to presenting himself and his medium than the picture at hand.

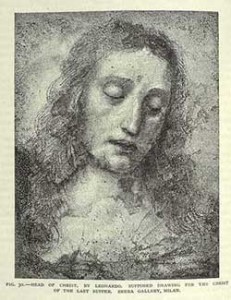

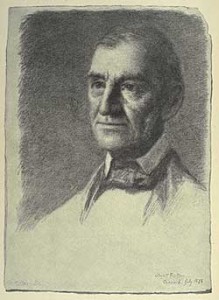

If photography and wood engraving intersected technically and conceptually in the late 1870s, it was their visual intersection that was the most evident and startling. In an engraving of Leonardo da Vinci’s Head of Christ that appeared in Scribner’s early in 1879, Timothy Cole reproduced not only the central figure but the texture of the chalk, discolorations across the paper, and tears at the bottom and the right, none of which Linton would have considered important (fig. 5). Cole’s engraved portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson, based on a crayon drawing by Wyatt Eaton and published in the following issue of Scribner’s, sought again to reproduce the rough texture of the original medium, as well as the shape (and now tint) of the paper (fig. 6). (In his Atlantic Monthly article, Linton singled out this engraving as especially bad, calling it “one undistinguishable mess of meaningless dots and lines.”)

What Linton and other critics recognized was that the conceptual and visual priorities of the new school carried the field of illustration closer to photomechanical reproduction. A. V. S. Anthony, a leading white-line engraver, noted early in 1880 that “reproductions of crayon, chalk, and brush effects lack the charm of firm, pure line” and “give nothing that the photograph would not give.” A writer for Art Interchange that same year was quite explicit about the congruence between the new school and “process” reproduction. “The popularity of the present style of wood engraving,” he wrote, “is in consonance with the strenuous efforts that are being made to bring the art of making fac-simile pictures to perfection.” Noting that “reproductive art, so considered, is purely mechanical,” the author averred that “modern engraving is the form that reproductive art assumes now.” Photomechanical processes, he said, were still “too crude” to be generally useful, so that the “imitative” imperative of the new school—”the effort being to obtain the same effects with the graver that the artist has given with his pencil”—was “a positive advance.” For Linton this was no advance at all, and it seemed amazing that wood engravers would push their medium closer to photoengraving. “For hand skillfulness alone, new processes will supersede that,” he warned in 1882, referring to photoengraving. The future of wood engraving would depend not on “mechanical excellence” but on “thoroughness in art.”

One path plotted out by the new school moved exactly in the direction that Linton feared. If the new imperative of the engraver was exact reproductive fidelity, then an engraving based on a photograph taken “from nature” would, ideally, look as much like the original photograph as possible. A photograph of Civil War General Joseph Hooker, for instance, taken during the war by Mathew Brady, was used for an 1886 illustration in the Century Magazine—formerly Scribner’s (compare figure 7 to Brady’s photograph of Hooker on the National Portrait Gallery Website). The wood engraving, based on the center portion of the photograph, was done by Peter Aitken (who was taught how to engrave by Cole) and quite clearly was a product of photography on the woodblock and of the strict reproductive fidelity of the new school. No detail is altered or missed in Aitken’s rendering, and the tonal range is far greater than anything that could have been achieved using traditional white lines and closer to the range that the halftone process would make possible. What is more, the “self-abnegation” of the engraver (whose name nonetheless appears at the bottom right), in seeking to transmit the image with as little evidence of his interpretive labor as possible, aspired to the principal aim of photoengraving, which was the removal of the “intervening” engraver altogether.

But there was another path suggested by the new school, one that led not to the purely photographic end of Aitken’s Hooker engraving but to ends more aesthetic even as they remained reproductive. It was this second path that Timothy Cole and other leading new-school engravers took: the engraving of works of art—especially paintings—for reproduction as wood-engraved prints. In 1883 editors at the Century decided to send Cole to Europe to begin engraving from “old master” paintings, a project that proved to be a great success and that kept Cole abroad and busy for more than two decades. His engraving of Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna and Child (from a larger altarpiece), which the Century published in 1890, is characteristic of that project, with its elevated subject and rich tones, and without the apparent imitation of texture, which critics had by now dismissed as gimmicky (fig. 8). Cole’s ability to produce engravings such as this one relied heavily on photography—diaries he kept while abroad show him constantly collecting photographs of art works and sending them to a photographer for transfer to woodblocks—and although the look here is very different from the Emerson portrait, Cole’s thinking about his work remained essentially the same. “Now the engraving is nothing, absolutely nothing,” he wrote to his editor in 1891. “It is the reproduction of the original alone that concerns me . . . The engraver must work in the spirit of the true artist, must aim to hinder his own individuality from acting. Must stand aside, make way for the artist. Must not speak his own words, nor do his own works, nor think his own thoughts, but must be the organ through which the mind of the artist speaks.”

Cole’s fantasy of reproductive transparency mimicked the ideal of photoengraving, but the product of that fantasy was far different than the halftone illustrations that were by now beginning to fill the pages of magazines. Indeed, by the time he wrote, wood engraving had come to be seen as a fine art in ways that were not true fifteen years earlier. Cole’s old masters series contributed to this development; so too did the activities of the Society of American Wood Engravers. Founded in 1882 and composed entirely of new-school engravers, including Cole, the society served as the institutional base for advancing American wood engraving as a fine art. When New York’s Grolier Club—devoted to the “promotion of the arts pertaining to the production of books”—held its first exhibition of wood engravings in 1886, the entire exhibition was comprised of work by members of the society.

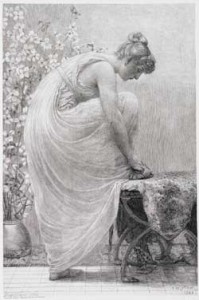

In 1887 the society published a book of members’ engravings in which all but one (out of twenty-five) were based on paintings rather than drawings. Frank French’s contribution to the volume, engraved after a Frank D. Millet painting called Lacing the Sandal, has little of the photographic quality of the new-school work from a decade earlier and shows a much more careful composition of lines than in, say, Cole’s Head of Christ, but it is not a return to white-line engraving (fig. 9). And the reproductive logic of the new school is clear (and reiterated) in the accompanying text. “Everything of Mr. Millet is here except the actual pigment,” wrote William Laffan. “Fidelity is uppermost in the engraver’s mind . . . To reproduce as faithfully as possible the thing to which he has addressed himself is his only thought.” Connoisseurs took great interest in wood engravings such as this one, especially as signed proofs printed on “Japan” paper. (By the early 1890s the Century Magazine was sending proof sheets to Cole for him to sign and return to help defray the expense of his being abroad.) In June of 1890 a writer for the Century, in an article entitled “The Outlook for Wood-Engraving,” noted the growing interest in American wood engraving as a fine art and urged museums to “begin the systematic collection of a fuller historical exhibit of hand-proofs,” insisting that “posterity should not be left to gather up in meager or incomplete examples the record of so marked an achievement.”

Linton would have none of it. In the decade after his Atlantic Monthly article, he wrote four books on wood engraving, all of which carried on his denunciation of the new school. About the time Cole’s Madonna and Child was published, Linton spoke before an art society in London where he once again took up the charge against what he was still calling the “new style of engraving,” pointing specifically to the Century Magazine as a chief purveyor of “pseudo-engravings” that had no art to them and that were, in the end, mere “photographic imitations.” “Pure photographs,” he said, “would . . . well replace them.”

By then halftones were beginning to take up the task of providing literal fidelity in illustration, indeed replacing engravings like Aitken’s J. Hooker. That is part of the more familiar story of the rise of the halftone and the decline of commercial wood engraving. But there was another story of photography in engraving on wood, one that pushed Cole and others to turn to art reproductions and that saw wood engravings moving through books and magazines and into museums and private art collections. Linton could not make sense of this second story, and he might have felt vindicated had he lived long enough to see that the career of new-school engraving as a celebrated fine art was fleeting. When Cole returned to the United States in 1910 he was hailed as a true artist (he was soon elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters), but there was little support for his work. By the time he died in 1931 he was already being called “the last of the wood engravers.”

Further Reading:

Anyone interested in understanding the various techniques for making prints can do no better than to start with Bamber Gascoigne’s How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet, 2nd ed. (New York, 2004). The most formative study of photography and prints in the nineteenth century is Estelle Jussim’s Visual Communication and the Graphic Arts: Photographic Technologies in the Nineteenth Century (New York, 1974). Jussim wrote after and in many ways in response to William M. Ivins Jr.’s Prints and Visual Communication (New York, 1969). On “art” engraving in the 1870s, see Sue Rainey, Creating Picturesque America: Monument to the Natural and Cultural Landscape (Nashville, 1994). For more popular wood engraving during the decades after the Civil War, see Joshua Brown, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley, 2002). William Linton has a full-length biography in F. B. Smith, Radical Artisan: William James Linton, 1812-97 (Manchester, UK, 1973). For a good discussion of Linton’s career during his campaign against the new school, see Nancy Carlson Schrock, “William James Linton and his Victorian History of American Wood Engraving,” in William J. Linton, American Wood Engraving: A Victorian History (Watkins Glen, N.Y., 1976). Studies that take up questions about photography and wood engraving include: Tom Gretton, “Signs for Labour-Value in Printed Pictures After the Photomechanical Revolution: Mainstream Changes and Extreme Cases around 1900,” Oxford Art Journal 28 (2005): [371]-390; Nancy Martha West, “Men in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Masculinity, Photography, and the Death of Engraving in the Nineteenth Century,” Victorian Institute Journal 27 (1999): [7]-31; Gerry Beegan, “The Mechanization of the Image: Facsimile, Photography, and Fragmentation in Nineteenth-Century Wood Engraving,” Journal of Design History 8 (1995): 257-274; and David Woodward, “The Decline of Commercial Wood Engraving in Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of the Printing Historical Society 10 (1974-75): [57]-83. See also Neil Harris’s highly influential essay “Iconography and Intellectual History: The Halftone Effect,” in Neil Harris, Cultural Excursions: Marketing Appetites and Cultural Tastes in Modern America (Chicago, 1990): 304-317. For a discussion of photography and wood engraving in the context of other graphic print media at the end of the nineteenth century, see Martha A. Sandweiss, Print the Legend: Photography and the American West(New Haven, 2002): chapter 7.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Stephen P. Rice is associate professor of American studies at Ramapo College of New Jersey and author of Minding the Machine: Languages of Class in Early Industrial America (2004). He is working on a new project on commercial wood engraving in the nineteenth century.