Print Culture and Popular History in the Era of the U.S.-Mexican War

The racial agenda preserved in nineteenth-century print culture resonates with contemporary U.S.-Mexico relations.

As a Latino scholar who recently completed a year-long postdoctoral fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society, I can’t approach researching the 1846 U.S. invasion of Mexico without being reminded of how the print archive preserves evidence of nineteenth-century racism that resonates with contemporary U.S.-Mexico relations. Consider this statement from Corydon Donnavan’s 1847 book Adventures in Mexico: “The fact need not be concealed, that from their meanest soldier to their best general, [the Mexicans] are a nation of liars and plunderers. There are a few honorable exceptions, it is true, but more modest epithets will not serve truly to portray their general character.” Mid-nineteenth-century American popular culture frequently made such claims, ascribing lawlessness and immorality to the Mexican people. The present essay offers some archival discoveries that show how American publishers played an active role in shaping portrayals of the Mexican War in U.S. print culture, in particular, by censoring the writings of U.S. soldiers before they appeared in the print public sphere. As we will see, some authors and publishers edited manuscripts before publication to remove evidence of illicit activity by the American military. In other cases, print itself was marshaled as evidence of U.S. superiority and Latin American underdevelopment.

While the origins of wide-scale U.S. racism against its southern neighbor can be dated to the Texas Revolution (1835-36), the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-48) was better able to mobilize popular print culture due to the newly industrialized book trade and emerging technologies that produced visual culture on a larger scale. The conflict provided the American army with a foreign war that doubled as exotic travel for volunteer soldiers, many of whom strongly identified with their Anglo-Saxon roots. Soldiers spread their assessments of Mexican culture in media formats that ranged from newspapers and printed books to lithographs, daguerreotypes, and moving panoramas.

A remarkable amount of writing produced by the American soldiery documents their experiences. More entrepreneurial souls like Corydon Donnavan (described in more detail below) wrote books, gave public lectures, and charged admissions to panorama exhibitions. In print and manuscript, soldiers made countless racist observations that were inflected by perceptions of Mexican political institutions, society, cuisine, and gender identities. For instance, Robert Armstrong, aid to General Winfield Scott, wrote his sister that the Mexican people are “totally incapable of self government,” blaming Catholicism for ruining their political system. Furthermore, many U.S. soldiers were avidly on the prowl for sex. Complaining of having few responsibilities to occupy his time, since fighting was infrequent, C.B. Ogburn wrote about the “Saltillo girls” who inspired him to engage in as many “tall sprees” as he could manage. Other soldiers were fascinated by vestiges of pre-Columbian history. The Lieutenant John Wolcott Phelps paid Mexican children to gather stone fragments from the pyramid at Cholula: “The latter always occurring in such a shape as to leave no doubt but that they are the broken and worn out knives which were used in the sacrifices.” Military officers such as Phelps recorded their observations in diaries as well as letters, which were often excerpted for publication in American newspapers; Mexican souvenirs sometimes were mailed home with this correspondence as well.

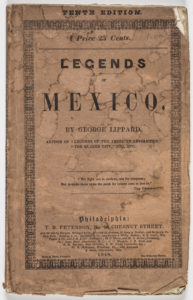

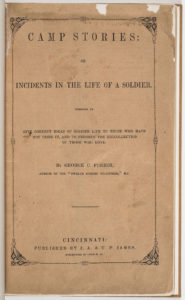

The U.S. invasion was culturally defined by this “scribbling soldiery,” a term used by the New York periodical Yankee Doodle in 1846 to describe the phenomenon of the soldier-turned-amateur author. My research has been illuminated by considering the original editions of soldiers’ narratives from collections held by the American Antiquarian Society and other institutions. In particular, I’ve been drawn to a hitherto unstudied pattern of erasure and omission of detail in published accounts, where the publishers and editors of these soldier-authors seem to deliberately omit the violence of the war. Modern scholars such as Robert Johannsen, Shelley Streeby, and Paul Foos have previously studied these Mexican War narratives, from cheap fiction by George Lippard and Ned Buntline to personal histories such as 1847’s Camp Life of a Volunteer. Novels such as Legends of Mexico (1847) and ’Bel of Prairie Eden (1848) helped justify the war to popular audiences by casting a narrative of Anglo-Saxon superiority over Mexico’s mixed-race population and weak level of state-formation. As ’Bel of Prairie Eden’s John Grywin put it: “Fifty white men of Texas are equivalent to one thousand Mexicans, any day.” Less noticed is the fact that Lippard’s texts themselves located authenticity in manuscript narratives of the Mexican War. ’Bel of Prairie Eden, for instance, drew from a fictional manuscript written by a “Soldier of Monterey.” Authors of fiction used the conceit of the “real” manuscript (even if they were making it up), just as popular accounts came from soldier diaries and letters. But manuscripts from the war didn’t appear in print without careful editing. By implication, it is the mediations between manuscript and print—the transmission from one medium to the other—that revealed the ideological constraints that made some perspectives on the war invisible to the public.

Paul Foos observes in his 2002 study A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair that many published personal narratives from the Mexican War are curiously silent regarding the conflict’s violence. American soldiers largely refrained from considering the moral implications of a military invasion against a poorly organized enemy. That said, my bibliographic analysis of the transmission of manuscript into print clarifies the ideological function of the war’s literature. In at least three instances, archival evidence proves that American publishers carefully edited soldier narratives to omit information that might contradict the war’s nationalist justification. For example, Camp Life of a Volunteer—a widely read history described by the historian Robert Johannsen as a “straight forward journal”—is anything but truthful. The University of Texas, Arlington, possesses the manuscript diaries of the soldier Benjamin Franklin Scribner that formed the source material for Camp Life of a Volunteer. On a recent visit to Arlington, I conducted a line-by-line textual comparison of the manuscript with the printed edition and found numerous divergences. Camp Life’s publisher (Philadelphia’s Grigg, Elliott, & Co.) omitted passages unfavorable to the military. Scribner’s reflections on his moral failings—moments of doubt and confusion regarding the war’s justification—were omitted from the published edition. American readers were never able to read that Scribner felt he was “acting a part in which my own character is not represented,” or that he had “dipped into all the temptations that have come in my way.” This latter statement offers a rare suggestion of the illicit activities of the U.S. military perpetrated upon the Mexican people. At the same time, because of the censorship, American readers never learned that Scribner occasionally wrote about how he abhorred the war, that he felt “alone and desolate in my social relations,” and concluded that in Mexico “the future has nothing in store for me.” Without these crucial statements, the voice of Camp Life of a Volunteer had a more tenuous relation to the manuscript sources than readers were led to believe. Grigg, Elliot, & Co. thus distributed a war narrative that sanitized Scribner’s account in such a way as to minimize political controversy and conceal evidence that U.S. soldiers were not always behaving their best.

When transformed into books, manuscript sources were carefully edited to suit the interests of publishers hungry to satisfy the print market. Consider a second example. In 1849, South Carolina’s H. Judge Moore published a personal history entitled Scott’s Campaign in Mexico, which sought to give greater credit for Southern distinction in the American victories led by Winfield Scott. Although Moore presented himself as writing with a “free and impartial hand, and an unbiased head,” comparison with his manuscript diary (held by Yale’s Beinecke Library) reveals a similar pattern of selective memory. For instance, missing from the printed version is Moore’s desire to “see a Mexican Donna” and “claim the promise made to Abraham that my seed should possess the land.” Moore’s published book therefore focused on the details of battle at the expense of the more complicated sexual factors that shaped his experience of the war. Such examples reveal the rhetorical frames that foregrounded particular experiences over others deemed less favorable or marketable. The project of nineteenth-century American autobiography, which historian Ann Fabian has summarized as the writing of a “plain, unvarnished tale,” proves in the Mexican War histories to be anything but plain or truthful.

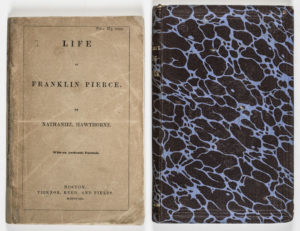

Consider a third case of doctored narrative: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s notorious campaign biography of his friend Franklin Pierce. Just in time for the 1852 election, Hawthorne aided Pierce’s bid for the presidency by writing a “political biography” whose intimate knowledge of the man derived from a friendship that began when both were students at Bowdoin College. Despite Hawthorne’s claim of impartiality, the author clearly manipulated the facts to represent Pierce as a hero of the Mexican War. In a decisive act of editorial manipulation, Hawthorne reproduced Pierce’s war diary as Chapter IV of the Life of Franklin Pierce. The author framed Pierce’s account by presenting it as authentic documentation: “They are mere hasty jottings-down in camp … but will doubtless bring the reader closer to the man than any narrative which we could substitute.” Hawthorne wished to bring the reader closer, but not too close. In fact, several crucial entries from Pierce’s Mexican diary were deliberately omitted from the biography published by Ticknor, Reed, and Fields.

It is worthwhile to understand Hawthorne’s act of message crafting as a later instance of the framing techniques and editorial strategies used in Camp Life of a Volunteer and Scott’s Campaign in Mexico. One passage Hawthorne chose not to include from Pierce’s camp writings is quite interesting; here Pierce writes for a need for ruthless military prosecution: “War, that actually carries, widespread woe & despoliation to the conquered and tacitly at least, allows pillage & plunder with accompaniments not even to be named during a campaign like this even in a private journal.” Obviously, this statement just wouldn’t do in a contested political campaign. And in a more subtle way, passages of this kind from Pierce’s diary dramatically undermine the ideological coherence of the U.S. invasion by suggesting that the American military allowed and implicitly promoted “pillage & plunder with accompaniments not even to be named.” Like the diaries of H. Judge Moore and B.F. Scribner, Franklin Pierce’s manuscript hints at aspects of the U.S. military invasion that might be described as war crimes. That said, these are only hints—literary expressions of sexuality, plunder, violence, and martial manhood—that cannot be precisely documented. Because Hawthorne’s Life of Franklin Pierce silenced these ambiguities of Pierce’s wartime experiences by leaving them out of the publication altogether, the campaign biography exemplifies the larger effort by American publishers to obscure the war’s history.

One printer turned public lecturer, Corydon Donnavan, asserted the dominance of American society over Mexico’s underdeveloped institutions by directly contrasting the printing trades—a purported marker of progress—of both nations. At the war’s outset, Donnavan worked as a clerk in the steamboat business, but he later monetized his experiences in Mexico when he became a public showman and exhibitor of moving panoramas in Cincinnati, Boston, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Here we see how sensational reading about the war operated within a broader media environment, as Donnavan used his panorama shows as promotional opportunities to sell Adventures in Mexico. A broadside for performances in Boston summarizes Donnavan’s multi-medial combination of panorama, oratory, and bookselling: “For several months a prisoner during the recent war in that country, will deliver an Explanatory Discourse, relating many incidents of the war, Mexican Life, Manners &c., as the Painting passes before the audience. His ‘Adventures in Mexico,’ a work of 132 pages, including an appendix descriptive of the Panorama, may be had at the Hall.” Among other events, the book made much of his capture in 1846 by a group of Mexican bandits, who sold Donnavan and several other men into slavery.

As recounted in Adventures in Mexico, the captors spared the Americans’ life when Donnavan explained that his fellow prisoners were job printers and not U.S. soldiers. In response, the bandit Poco Llama decided to sell the men as labor in a Mexican printing office. The captives were then taken from Camargo on a long march through Coahuila stretching from Monclova to Parras. From there Donnavan and company were taken farther south to Sombrerete, to Fresnillo, and finally to modern-day Zacatecas (then known as Valladolid). While some parts of the story are undoubtedly fictionalized, even the imaginary aspects of Donnavan’s tale contain their own explanatory power, insofar as Adventures in Mexico offers another index of the various ways U.S. print culture conjured its Mexican enemy as the opposite of democratic modernity. In particular, Donnavan focused on a printing press as the symbol of Mexico’s postcolonial underdevelopment. Here is his description of a decrepit hand press used to print newspapers in Valladolid:

In printing, as well as other arts, mechanics, and agriculture, the Mexican people are at least two centuries behind the age. Their type and presses, like their muskets, are generally the worn out and cast-off material from England. The old Ramage presses were so venerable they could scarcely stand alone, and at each successive revolution of the rounce their shrieks would grate upon the ear, as if exercise was as painful to them as to the Spanish printers who were torturing their old joints.

There’s a bit of irony here: Ramage presses were actually relatively recent, first sold by Adam Ramage from Philadelphia in 1800. But the larger point made by Donnavan contrasts the print modernity of the United States (the nation’s steam presses, stereotyping plants, paper factories, etc.) with the backwardness of a Mexican newspaper still locked in the hand press era. Print technology, in other words, was the vehicle for Donnavan’s racist bias. He was especially insulted that the Mexican printers set type while sitting down: “The cases, instead of being mounted on stands, are spread out on the floor, as the Spaniard, being too lazy to take a perpendicular position, prefers to sit down to set up type; and on a filthy mat, thrown out upon the floor, he sprawls himself at his occupation, where he will sometimes succeed in setting three thousand em’s per day.” Punning on the homonym sit/set, Donnavan draws a seamless connection between backwards print technology and backwards printing practice. Surely a nation that lazily sits down to set type, rather than standing at an orderly type case, doesn’t have the political will to exercise sovereignty. If, as U.S. politicians suggested, Mexico didn’t have a functioning republic, then it stands to reason that part of that dismissal is rooted in values similar to Donnavan’s claim that Mexican printing, “as well as other arts, mechanics, and agriculture,” are obsolete by several centuries.

But Donnavan’s disgust at bad printing turns out to be misplaced. First, we should note that Ramage presses were produced in the United States, and therefore Donnavan ends up chastising Mexican print culture for striving to resemble its northern neighbor. But the Ramage press was not the only irony. Despite his accusation that Mexican printing is riddled with mistakes, the first edition of Adventures of Mexico erroneously lists its year of publication as 1487. The supposedly superior printing abilities of the American press produced the first edition of Adventures of Mexico with a glaring printer’s error right on the title page. In the process of arguing that the printing press itself distinguished between Mexico and the United States, American printers inadvertently left a corpus of badly printed books that contradict the central premise of that argument.

U.S. print culture in the era of the Mexican War demonstrates how the American republic’s first foreign war brought together nationalism and the print market in ways that anticipated the role of modern mass media in shaping public responses to warfare. Both the content of American book publishing (soldier narratives, military histories) and the media formats themselves (the technologies of text production and visual culture) worked in the service of propagandizing a war that, as Amy Greenberg reminds us, did in fact have a vocal minority of critics in the public sphere. That these works of public “history” were, more often than not, either highly selective in their presentation of facts or downright fictitious shouldn’t lead us to overlook the political implications of Mexican War literature. Quite the contrary. As demonstrated here, the Mexican War is an important flashpoint in tracing a longer history of the tactics of a mass press that transformed its source material into fodder for popular reading. The war inspired racist stereotypes about a nation (Mexico) and an ethnic category (Latinos) that remain crucial elements of American hemispheric and transnational cultural politics.

Further Reading

The classic treatment of the U.S.-Mexican War in popular culture is Robert Johannsen’s To the Halls of the Montezeumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination (New York, 1985). Shelley Streeby’s American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture (Berkeley, 2002) offers the best analysis of Mexican War fiction. For a recent history emphasizing popular opposition to the war within the United States, see Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York, 2012).

Robert Armstrong’s Feb. 13, 1848, letter to his sister is from the Mexican War Collection, University of Texas, Arlington, Special Collections. C.B. Ogburn’s December 1847 letter from Saltillo is held by the New-York Historical Society. John Wolcott Phelps’s diaries from the Mexican War are at the New York Public Library, Manuscript and Archives Division. In A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War (Chapel Hill, 2002), Paul Foos recovers the experience of American soldiers and notes their reticence in writing about military violence. Peter Guardino explores a fascinating comparative study of Mexican and U.S. soldiers in “Gender, Soldiering, and Citizenship in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848,” American Historical Review 119.1 (2014): 23-46.

On the varieties of nineteenth-century American autobiography, see Ann Fabian, The Unvarnished Truth: Personal Narratives in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley, 2000). The full text of the published editions of Camp Life of a Volunteer (1847) and H. Judge Moore’s Scott’s Campaign in Mexico (1849) are available via the Internet Archive. The manuscript diaries of Benjamin Franklin Scribner and H. Judge Moore are available at the University of Texas, Arlington, and Yale University’s Beinecke Library, respectively. Scott E. Casper discusses Hawthorne’s biography of Franklin Pierce in Constructing American Lives: Biography & Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, 1999). Franklin Pierce’s Mexican War diary (1847) is held at the Huntington Library and is microfilmed as part of the Franklin Pierce Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

For a helpful summary of nineteenth-century printing presses I consulted Elizabeth M. Harris, Personal Impressions: The Small Printing Press in Nineteenth-Century America (2004).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.1 (Fall, 2016).

John Garcia is currently lecturer in humanities at Boston University’s College of General Studies and a visiting instructor in the English Department of Clark University. He was the 2015-16 Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in American Literature at the American Antiquarian Society, and has held Mellon fellowships at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies and the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. His research on book distribution and the print culture of the U.S.-Mexican War is part of a larger project on bookselling in early America.