Early in the 1980s, at one of the first Oxford University symposia on food, I was asked to speak on the subjects of American culinary history and the history of American cookbooks. As the founder and proprietor of Ann Arbor’s Wine and Food Library, America’s oldest antiquarian bookshop devoted solely to the culinary arts, I must have seemed like a logical choice for this kind of presentation. But whatever this sophisticated and international audience thought about my bona fides as a food historian, they were somewhat incredulous that I could speak on topics as odd as American culinary history and American cookbooks. They said America had no cuisine or culinary history to speak of; all we ate were hamburgers and fries, with ketchup! Having spent more than a year preparing for the lecture, I knew they were wrong. I came home determined to learn more about American culinary history and to share what I learned.

Enter John Dann, who was then director of the Clements Library for American history at the University of Michigan. John had been a client of my bookshop and obviously shared my passion for this aspect of American history. From the beginning, John agreed with my very broad definition of American culinary history as everything that influenced or influences America and everything that America influenced or influences in culinary matters. Shortly after I returned from Oxford, John asked if my husband, Professor Dan Longone, and I would present an exhibition of our culinary books at the Clements Library. Motivated, perhaps, by the same prejudices that characterized my audience at Oxford, we first planned to show European works, many of them beautifully bound and illustrated. But we realized that since Clements was an Americana library, we ought to show our American imprints. It was a momentous decision, as it turned out. We were surprised and dismayed to learn that no one had ever mounted such an exhibition accompanied by a scholarly catalogue. Ours would be the first. In 1984, Dan and I co-curated our first Clements exhibition, “American Cookbooks and Wine Books,” and co-authored the accompanying monograph. This first marked the start of our richly satisfying collaboration with the Clements Library.

By the mid-1980s, the Clements had a very small but select collection of culinary material. Over the next decade and a half, as volunteers at the library, we began to see a larger, more coherent collection emerge. We were happy to be part of the process! After all, Dan and I had spent much of our adult lives creating collections of books on food and wine intended to define the American culinary experience. In 2000, I accepted the pioneering position of Curator of American Culinary History with the mandate from John Dann to develop an unequalled research collection.

Tenure at the Clements proved to be quite an education. Dan and I soon realized that the meshing of the Clements holdings with our own collections would create the kind of archive that would fulfill John’s mandate and our vision; thus we donated our collections to the library. Over the years, many bookshop clients generously donated their collections as well. Dedicated volunteers, old friends and new, helped this project in other ways. Together, they have donated about 50,000 hours in the last ten years and, along with the Clements staff, have developed new methods of descriptive cataloging. Staff and volunteers now examine and catalogue not only the culinary archive but all of the rich Americana holdings in all divisions (books, manuscripts, maps, graphics) for their culinary content.

The Spring-Summer 2005 issue of The Quarto, the semi-annual newsletter sent to members of the Clements Library Associates, was devoted to the First Biennial Symposium on American Culinary History: Dedication of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive and Inauguration of the Longone Center for American Culinary Research. Announcing the JBLCA, John Dann summed up the academic importance of culinary history:

Fifty years ago or more, wars were generally seen to be won or lost on the basis of military strategy or battlefield heroics. Today, historians are as likely to emphasize deficiencies in supply lines or perhaps disease caused by malnutrition … Historians are finally coming to realize that diet, the production of and commerce in foodstuffs, and cookery are not only important but are actually defining characteristics of a nation’s culture.

In 2010 the University of Michigan expressed its plans to establish culinary history as a scholarly research specialty.

This brief history of one archive, the JBLCA, is part of a larger story about the vitality and visibility of food studies. Culinary history classes and programs are increasingly reaching more students at all levels as well as interested amateurs throughout the United States and elsewhere. This would not be possible without the growth of culinary archives, which have preserved the historic literature in the field. Some are small, regional collections or are limited to a specific subject, but there are now a goodly number of broad and large archives available to the researcher. Significant institutional holdings now exist throughout the country, from New England to the West Coast, where they fuel new directions in diverse academic fields.

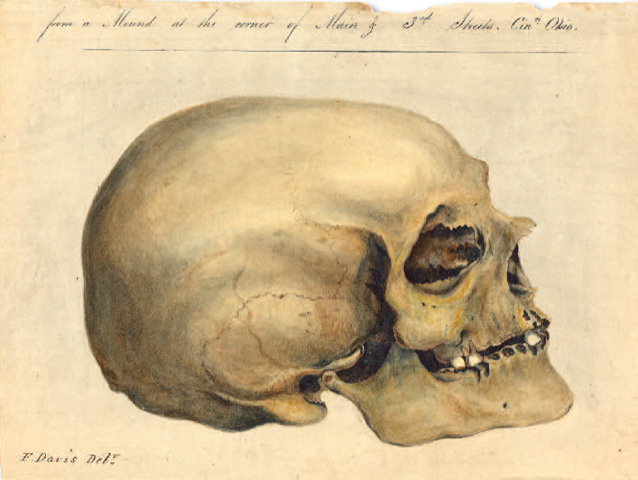

The range and diversity of the images below speak not only to the state of the field but also to the strength of the JBLCA; selecting highlights for this issue of Common-place was very difficult. Each image was chosen to represent many others in our holdings. The archive is notable for containing not only most of the essential “high spots” in the field, but for strong holdings for related areas of interdisciplinary study. It contains about 25,000 items, about one-third of which are cookbooks. The archive is a work in progress and not all of our holdings are yet cataloged. But cataloging continues apace and we add to the total every week.

Please click on any thumbnail below to view images.

Illustration from Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, by Thomas Harriot. Illustrations by John White, engraved by Theodor de Bry (Francoforti ad Moenvum, 1590). Courtesy of the Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Map of Butter and Cheese Factories of New York State, by the Commission of Agriculture, State of New York (Albany, 1899). Courtesy of the Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi, by Bartolomeo Scappi (Venice, 1622). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Title page from Tractatus de Vinea, by Prospero Rendella (Venetiis, 1629). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page and frontispiece from The Compleat Housewife, by E. Smith (London, 1741) Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Title page and frontispiece from Culinary Chemistry, by Frederick Accum (London, 1821). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Title page and frontispiece from Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine, by Alexandre Dumas (Paris, 1873). Katherine Bitting’s copy with her bookplate. Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from first edition of American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons (Hartford, 1796). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from The House Servant’s Directory, by Robert Roberts (Boston, 1827). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Cover from A Treatise on Bread, and Bread-Making, by Sylvester Graham (Boston, 1837). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from Everybody’s Cook and Receipt Book: but more particularly designed for Buckeyes, Hoosiers, Wolverines, Corncrackers …. by Mrs. Philomelia Ann Maria Antoinette Hardin (Cleveland, 1842). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from The Indian Meal Book, by Eliza Leslie (Philadelphia, 1847). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Title page from A Poetical Cook-Book, by M.J.M. [Maria J. Moss] (Philadelphia, 1864). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page and frontispiece from The Market Assistant, by Thomas F. De Voe (New York, 1867). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from Jewish Cookery Book, by Mrs. Esther Levy (Philadelphia, 1871). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Cover from National Cookery Book, by Women’s Centennial Executive Committee (Philadelphia, 1876). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cover from The Way to a Man’s Heart. “The Settlement” Cook Book, by Mrs. Simon Kander and Mrs. Henry Schoenfeld (Milwaukee, 1903). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Title page and frontispiece from A Thousand Ways to Please a Husband, by Louise Bennett Weaver and Helen Cowles LeCron (New York, 1917). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cover from The Mary Frances Cook Book, by Jane Eayre Fryer (Philadelphia, 1912). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Title page from Chinese and English Cook Book, by Fat Ming (San Francisco, 1910). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

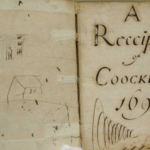

Title page from A Receipt Book of Coockery, manuscript cookbook (England, 1698). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Cover from The Boston Cooking School Magazine (December 1906). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Title page from A Short History of the Banana, advertising ephemera by the United Fruit Company (1904). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Menu of the American Maize Banquet, (Copenhagen, 1893). Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

The front and rear covers of the Chez Panisse Bastille Day Menu (Berkeley, California, 1973). Jeremiah Tower Collection. Courtesy of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Jigsaw puzzle (2006), based on a tin advertising sign from about 1906. Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The Porcineograph: A Gehography of the United States, by William Emerson Baker (Wellesley, Massachusetts, 1876). Courtesy of the Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Poster for the Clements Library Exhibition The Old Girl Network: Charity Cookbooks and the Empowerment of Women (Ann Arbor, 2008). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cover of the program for the First Biennial Symposium on American Culinary History: Dedication of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive and Inauguration of the Longone Center for American Culinary Research (Ann Arbor, May 2005). Courtesy of Jan and Dan Longone, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.3 (April, 2011).

Jan Longone, curator of American culinary history at the Clements Library, University of Michigan, and proprietor of the Wine and Food Library, an antiquarian bookstore, is a member of the editorial board or contributor to the Oxford Companion to Food, the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, The Quarto, Gastronomica, and the University of California series Studies in Food and Culture. In 2000, she received the Food Arts Silver Spoon Award in recognition of her scholarly determination to preserve and honor American culinary literature and her many other contributions to food history.