Bloomfield, New Jersey, bookbinders’ tool maker

It all started in June 2006 when my good friend and mentor Sue Allen asked me what I could find out about Samuel Dodd, a nineteenth-century New Jersey engraver. In 1998 I took Sue’s course on publishers’ bookbindings at the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. After having spent the previous twenty-five years collecting books on nineteenth-century science and technology, my focus made an abrupt shift from the contents to the covers of books.

I first encountered Samuel Dodd in 2001 at a book fair where I purchased a friendship album, also called an autograph album, published by John Riker of New York and dated 1836 (fig. 1). The stunning embossed leather cathedral design is subtly signed S DODD N JERSY at the base of the stained glass window in letters only 1/32 of an inch high (fig. 1a).

My extreme nearsightedness has proven to have a silver lining. It allows me to see extremely fine print without a magnifying glass, and I believed that I had discovered an important new American embossed binding example. When I got home, I was dismayed to find that Edwin Wolf 2nd, former librarian of the Library Company in Philadelphia, had already discovered Dodd. He illustrated an identical example, although dated 1835, in his bible on embossed American bindings. Wolf reported relatively little information on Samuel Dodd other than that he was an engraver from Bloomfield, New Jersey, a rural town three miles northwest of Newark. Although virtually unknown today, Dodd’s engraving skills were recognized at the prestigious annual American Institute Fairs in New York. He won a silver medal for the best bookbinders’ stamps in 1848 and a diploma in 1855 for bookbinders’ ornaments.

Sue Allen knows that I love to research obscure people, and I swallowed the hook. I immediately began to search online and microfilm census databases and city directories. In addition to Samuel Dodd’s 1850 and 1860 census records, I located a valuable Dodd family history. There, I learned that Samuel Dodd was born on April 7, 1797, in Bloomfield; married Elizabeth Young Baldwin on April 3, 1823; had six children; and died in Bloomfield on August 1, 1862.

I then found a tantalizing online reference to archival materials in the Winterthur Library from the Newark engraving business of Samuel Dodd’s two sons, William H. C. and Walter S. Dodd. In addition to several hundred 1860s and 1870s letterheads, there was a design book with thousands of engraved images used in the son’s engraving business.

I faintly hoped that there might be some mention of Samuel Dodd in his sons’ records. I soon visited the Winterthur Library, just ten minutes away. It was one of those rare and wonderful moments of discovery. The instant that I saw the design book, I realized that it was Samuel Dodd’s own pattern book. The designs are not in fact engraved but instead are smoke proofs of bookbinders’ hand stamps and plaques. Smoke proofs are made by holding the engraved brass stamp in a sooty candle flame and stamping the resulting blackened engraving onto paper or leather. These were used to track the progress of the engraving and filing process, as well as to provide a lasting impression for future duplication.

Two major clues suggested that this was the working pattern book of Samuel Dodd and not of his sons:

- The paper appears to be early nineteenth century laid paper and not from the 1860 period. Also, the style of the stamps appears to be much earlier than the sons’ working dates of the 1860s to 1870s.

- A large corner plaque, number 580, caught my attention because it looked vaguely familiar (fig. 2).

I excitedly went upstairs to Winterthur’s reference library and located a copy of Edwin Wolf’s definitive reference for American embossed bindings. I was both amazed and thrilled to find that the unique corner design in the Dodd stamp catalog appeared to be the same one used on the ca. 1835 Riker album with the signed Dodd cathedral design (fig. 3).

As I marveled over the eighty individual leaves, it became apparent that Dodd’s pattern book was assembled chronologically as each tool was made, probably starting in the early 1820s. Sometime later in the century, the individual five-inch by seven-inch leaves from the small notebook were pasted onto muslin with two leaves per page. The pattern book was then sturdily bound in suede, to protect the contents from rough handling in a dirty workshop environment.

Considerable planning went into the pattern book. Dodd initially ink-ruled each page into one-inch by one-inch grids, sequentially numbering each square in ink. As each stamp was completed, Dodd made a final smoke proof in the center of each grid (fig. 4). A stamp larger than the gridlines was stamped onto paper, which was then cut out and glued into the pattern book, because this size is generally too big for a binder to hand stamp and still get a sharp impression. These large stamps would have been engraved on flat plates, called plaques, for a press, rather than for bookbinders’ hand tools.

In this way, over a working period of approximately thirty-five years, Dodd systematically constructed a pattern book of twenty-five hundred numbered and priced stamps (fig. 5).

The total price for all twenty-five hundred stamps is approximately forty-five hundred dollars, an average of under two dollars per stamp. The cheapest stamp is ten cents and the most expensive is fifty dollars for the large four-corner plaque used on the ca. 1835 Riker album with the cover design signed by Dodd.

In addition to these bookbinders’ stamps, there are many pages of designs for plaques for stamping borders and entire book covers in blind (i.e., without gilt). There are even a few designs for stamping the velvet in daguerreotype cases.

There are also a number of advertising or ownership stamps for hotels, hat manufacturers, and libraries. American clients included locations in Rochester, New York; New York City; Newark, New Jersey; Montgomery, Alabama; Alton, Illinois; and Columbus, Georgia. Stamps were made not only for customers in the United States but also in Mexico City and Paris. Clearly, the world of Samuel Dodd encompassed far more than just designing and cutting a single large plaque for a mid-1830s friendship album.

A stunning stamp of a three-inch-tall winged lyre with a Masonic all-seeing eye was also vaguely familiar. Winterthur agreed to make me a photocopy of this stamp along with four other pages for further research.

As soon as I returned home, I immediately compared the smoke proof of the corner plaque number 580 (fig. 2) with my red morocco copy of the Riker album with the cathedral binding signed by Dodd (fig. 6). It was a thrilling moment to see the agreement.

I next located my copy of an 1833 John Riker album with a winged lyre (fig. 7). The Dodd pattern book winged-lyre stamp, number 561 (fig. 8), proved to be identical to that used on the cover of this album.

Now convinced that this was Samuel Dodd’s pattern book, I began to study him in earnest to learn as much as possible about this little-known engraver and bookbinders’ tool cutter.

I soon discovered bookbinder Tom Conroy’s exhaustive reference book on bookbinders’ tool cutters. I had several discussions with Tom, who patiently educated me on many aspects of bookbinders’ tool making. I was astonished when he told me that this is the only example of an original American bookbinders’ pattern book that he had heard of, which was a thrill for both of us. Well-known bookbinders’ tool cutter firms, such as John Hoole in New York and Gaskill and Copper in Philadelphia, published valuable nineteenth-century trade catalogues of bookbinders’ tools. However, these are re-engraved facsimiles of tool designs for multiple copies of catalogues and not proofs for a single working catalogue.

Tom Conroy had researched Samuel Dodd in the Newark City Directories and located his first appearance in 1849 as “engraver, Bloomfield.” I decided to take a fresh look and checked every advertisement, starting with the first Newark directory in 1835. I confirmed that Samuel Dodd did not appear in the alphabetical listings until 1849 but then discovered he took out a wonderful full-page engraved ad in 1848 (fig. 9).

Dodd used the same engraved border from 1848 through 1851, with only minor text or font changes.

This ad explains much about Dodd’s bold marketing techniques, as well as his versatile engraving skills. Not only did he advertise himself as a bookbinders’ tool cutter, but he also promoted his diverse engraving trade with charming vignettes. These depict stamps, rolls, scrolls, lines, sides and backs for books, stamps for saddlers and trunk makers, and embossing rolls and plates. In addition, there are vignettes for engraved door and bell plates, ornamental plates for harness makers, and dies for stamping silk hatbands for hatters. Newark was a major center of the hat making industry, and virtually all hats contained a silk hatband with the hat maker’s name stamped in gilt.

The doorplate vignette is proudly emblazoned S. DODD, further advertising his name and showing his self-promotion. In all likelihood, Samuel Dodd himself engraved the border for the ad, as he certainly had the technical capability.

The text within the engraved border also offers valuable historical information. It confirms that Dodd’s engraving business was located in Bloomfield, rather than in Newark as is often claimed. However, Dodd cleverly used several popular locations in Newark for customers to drop off and pick up engraving work, to make it more convenient by avoiding a carriage or train trip to rural Bloomfield. Dodd’s drop-off points occasionally changed between 1848 and 1851 and included a bookbinder, a printer, a drug store, and a coffee shop.

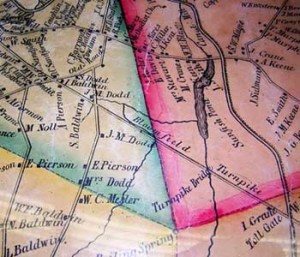

In 1851, Dodd advertised his business as “A few rods from the Turnpike Road, leading from Newark to Bloomfield, NJ.” A rod is around sixteen feet, and the 1850 Essex County New Jersey property map shows S. Dodd’s house, as advertised, just off the Bloomfield/Newark turnpike (fig. 10). His home no longer stands.

Another serendipitous discovery occurred while searching the manuscript collection card catalog of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for the only known Samuel Dodd line engraving. This is an undated trade card for the Washington Bleach Works, signed S. Dodd Sct.-New Ark. Although the historical society was unable to locate the engraving, I found a reference to a silhouette identified as “Saml. Dodd.” Unfortunately, there was no provenance, date, or a place, and this is a relatively common name. The silhouette is of a young man, identified only on the reverse as Saml. Dodd, father (fig. 11).

However, when I studied the entire group of eight Dodd silhouettes in the collection, the family relationships I had found earlier in the Dodd genealogy read like a DNA analysis. This silhouette is indeed that of a young Samuel Dodd, the New Jersey engraver, along with two siblings, his mother, and several members of his mother’s family. All the silhouettes are hollow cut and of a similar style and are backed by black silk fabric. They appear to have been cut at the same time, around 1815-1820, by the same artist. Samuel Dodd’s father, also Samuel, a farmer, died unexpectedly in 1815, when Samuel Jr. was seventeen years old. As the oldest of nine then-living children, the pressure on Samuel to begin earning a living must have been tremendous.

It appears very likely that Samuel Dodd apprenticed as a young man in the Newark, New Jersey, shop of well-known engraver Peter Maverick, as a lot containing the Washington BleachWorks trade card was sold at the auction of Maverick’s print shop upon his death in 1831. Hopefully an example of Samuel Dodd’s line engraving work will surface.

With the generous help of book historians, librarians, and book dealers, further research has led to the identification of several additional Dodd stamp patterns on spines or covers of books. These range in date from as early as 1827 to as late as 1862, the year that Dodd died. Work continues to identify additional stamps on books, and a facsimile of the pattern book will be published to aid other researchers.

A clue to Dodd’s resting place is offered in his obituary notice, first posted in the Newark Daily Advertiser on August 1, 1862. “Died, At Bloomfield, on the 1st inst., Samuel Dodd, in the 66th year of his age. Notice of funeral tomorrow.”

Dodd’s funeral notice appeared in the Newark Daily Advertiser for Saturday, August 2, 1862. “Died at his residence in Bloomfield, on the 1st. inst. Samuel Dodd, in the 66th year of his age. The relatives and friends are respectfully invited to attend his funeral from the Presbyterian Church on Sunday at 3 PM. The relatives will meet at the house at 2 ½ PM.”

This confirms that Samuel Dodd’s final residence was in Bloomfield and also that he was a member of the Presbyterian Church. The present Bloomfield Cemetery is connected with the old Presbyterian Church. After several hours of searching in a light rain, I was able to find Samuel Dodd’s gravestone among the multitude of Dodds. He is buried in a simple family plot with his father, mother, wife, and two daughters (fig. 12).

This stamp pattern book opens up a rare glimpse into a small nineteenth-century American business, revealing just how many designs one man produced in his lifetime. Bookbinders’ stamps were only one part of Dodd’s many engraving skills, which suggests that he had to significantly broaden his customer base in order to make a living. There would have been additional Dodd pattern books, and hopefully other examples will surface. This example had been undiscovered for thirty years.

Further Reading:

The finding list for the Dodd Collection at Winterthur Library is available online. Several Riker albums are illustrated in History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy—Riker. Major collections of nineteenth-century friendship or autograph albums are located in the American Antiquarian Society and the Library Company of Philadelphia. Illustrations of modern bookbinding tools are in Fine Cut Graphic Imaging Limited—Bookbinding Equipment. For a thorough treatment and exhaustive directory of tool cutters, see Tom Conroy, Bookbinders’ Finishing Tool Makers, 1780-1965 (New Castle, Del., 2002). For a detailed study of American embossed bindings, see Edwin Wolf 2nd, From Gothic Windows to Peacocks (Philadelphia, 1990). For an excellent genealogy of the Dodd family, see Allison Dodd and Rev. Joseph Fulford Folsom, Genealogy and History of the Daniel Dod Family in America: 1646-1940 (Bloomfield, N.J., 1940). See also John Littell, Family Records or Genealogies of The First Settlers Of Passaic Valley (And Vicinity) Above Chatham—with Their Ancestors and Descendants As Far As Can Now Be Ascertained (Feltville, N.J., 1851). The section from Davis to Dodd has been transcribed.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.1 (October, 2007).

Steve Beare is a retired research chemist. In addition to studying nineteenth-century book cover design, he is writing an online Directory of Nineteenth-Century American Scale Makers.