Those who adore archival research often imagine coming upon a find as glorious as the spectacles Nicholas Cage digs from Independence Hall in the movie National Treasure. The project that currently occupies my days is an inversion of this romantic ideal—think something more along the lines of National Trash. I too spend a great deal of time excavating with exhilaration, but instead of glorious and legendary relics of faux American history, I am searching for smut, digging for the materials that survived the attacks of legendary censor Anthony Comstock (fig. 1).

My interest in Comstock began during research on the artist Thomas Eakins. Diaries, letters, and board minutes from the late nineteenth-century art scene in Philadelphia and New York often referred off-handedly to Comstock as a threat to be avoided. Artists, trustees, and administrators altered exhibition and publication plans, debating how to avoid prosecution. Others held a “bring it on” attitude—many in the art world wanted to be the hero who defeated Comstock.

Those who nervously censored themselves were not wrong to take seriously the threat of prosecution. Born in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1844, Comstock was raised in a family of evangelical Congregationalists who believed, like their Puritan ancestors, that lust, intemperance, and lewdness were the causes of man’s downfall. After brief service in the Civil War, Comstock moved to New York City, and was shocked by the vice he found there. With the aid of backers at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), Comstock helped create the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV) in 1873, and then served as its secretary, and as an inspector for the U.S. Postal Service, until his death in 1915. During his career, Comstock held broad prosecutorial authority; following passage of the federal Comstock Act in 1873, his puritanical aesthetics served as the legal definition of obscenity in many American courtrooms. In his first empowered year alone, Comstock destroyed 13,000 pounds of books, 200,000 “bad pictures,” and 14,000 pounds of stereotype plates for printing books— and sent forty perpetrators to jail for a combined twenty-seven years.

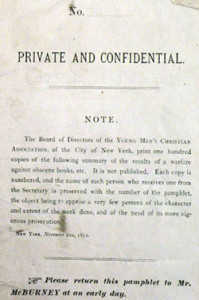

Searching for the prey of an effective censor makes the thrill of discovery especially tantalizing, since the “treasure” is not meant to be found. A good example is a thoroughly obscene pamphlet Comstock himself authored in 1872—a “PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL” report to the directors of the YMCA in New York, informing them of “the baldest facts” regarding the dangerous materials in their midst (fig. 2). Readers must have been titillated before even turning the first page, as the cover text promised description of “a warfare against obscene books, etc.” The 100 copies were each numbered, “and the name of each person who received one from the Secretary was preserved with the number of the pamphlet.” Robert McBurney, then secretary of the YMCA, presumably retrieved the distributed copies and burned them. The unnumbered pamphlet reproduced here may be the only surviving 1872 version—an example of careful record-keeping, as it resides today in the Committee Files of the Kautz Family YMCA archives at the University of Minnesota. This document is the kind of thing one can only find by emphasizing the “search” aspect of research. After YMCA staff in New York directed me to their colleagues in Minnesota, I applied for a travel grant, and spent two weeks in Minneapolis reading through every file relating to the New York branch between 1868 and 1878, hunting for evidence of Comstock’s earliest efforts.

In 1872, the YMCA’s Committee for the Suppression of Vice was raising funds to provide financial backing for Comstock’s work. Comstock emphasized the direness of the situation by listing items he had already destroyed, including: “Thirty thousand articles made of rubber for indecent purposes, viz.: the prevention of conception for the use of both sexes; “dildoes” (that being the trade name), made of stout rubber, and in the form of the male organ of generation, for self-pollution; five thousand five hundred playing cards which, when held to the light, exhibit obscene pictures;” and more than 125,000 books “known as the writings of ‘Paul de Kock.'” Finding this bit of smut was a definite thrill amidst the numerous less-fascinating accounts of building expenses and daily programs.

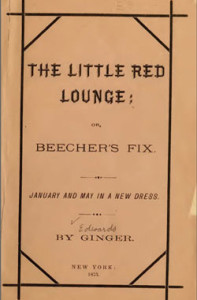

Given the elaborate efforts made to prevent its circulation, the 1872 pamphlet in Minneapolis is a fortuitous survivor. Thankfully for a smut-hunter’s sake, such survivals happened more often than Comstock would have liked. In late 1872 and 1873, it was widely reported in the press—most famously in Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly—that Theodore Tilton said he had seen his wife, Elizabeth, having sex with their Preacher on “a little red lounge.” In 1875, an author calling himself James C. Edwards (or “Ginger”) published a lengthy and somewhat bawdy poetic account of the reputed affair. “The Little Red Lounge; or Beecher’s Fix” (fig. 3) survives in two printed versions in a handful of collections, including the Library of Congress and Houghton Library at Harvard University. The prose is delightfully indecent:

There lived in Brooklyn, high above the bay,

A Pastor old, with spirit light and gay;

Of gentle manners as of generous race;

Blest with much sense, true inwardness and grace.

Yet, led astray by VENUS’ soft delights,

He scarcely could rule some idle appetites;

For all we know, since NOAH and the flood,

The best of pastors are but flesh and blood…Full soon the sheets were spread and Bess undress’d;

The room was perfum’d, the red lounge was bless’d.

What next ensued beseems me not to say;

Although the poem’s euphemisms today seem more witty than outrageous, Comstock’s Congregationalist sensibilities were provoked. He had already assisted in the prosecution of Victoria Woodhull, and destroyed many of her weekly newspapers recounting the alleged affair. On October 27, 1875, he arrested Hugh McDermott, editor and proprietor of the Jersey City Herald, and his fifteen-year-old son, for selling copies of “The Little Red Lounge.” Comstock recorded the progress of the case meticulously in a truly spectacular treasure “from the vault”—the NYSSV arrest blotters preserved in the Library of Congress: “McD. attempted to defy law & this Society. This pamphlet is a plagiarism on [Alexander] Pope, with Beecher’s name dragged in … He had 12,000 printed & had sold about 100 …” Although Comstock failed in three different courts to get a judge to take the case, he nevertheless won the battle: the “obscene matter” was destroyed, leaving the publisher out a good deal of money. This was a common outcome of Comstock’s raids. The arrest blotters detailing cases such as this have been used by several scholars in the past, and microfilmed versions may even be borrowed via inter-library loan.

It may seem surprising that in the year of its trial, “The Little Red Lounge” was “entered according to an Act of Congress … in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.” However, this often was the case, with censored books sometimes kept in locked cages or back rooms. Today, there are few titles that are not freely circulated, and in the age of the Internet, it is remarkably easy to find books that stoked incinerators more than a century ago. I began by compiling a list of book and picture titles in the NYSSV arrest blotters. Using a variety of databases such as WorldCat, the Library of Congress catalogue, and Google scholar searches, I found at least one copy of almost everything Comstock wished I would never see, and (ironically) received copies of several of these, shipped through the mail, via inter-library loan. My special goal as an art historian was to find illustrated books—of course, they are much more fun anyway.

A particularly amusing example of a censored book is Le Nu de Rabelais, d’apres Jules Garnier, par Armand Silvestre, Illustrations de Japhet, which the College of Holy Cross librarians kindly shipped to our librarians at Saint Michael’s College. French books, pictures, and “rubber goods” make up a significant percentage of the material Comstock pursued, hardly surprising to historians of the gilded age. Le Nu abounds with preposterous Rabelaisian adventures and cavorting nudes. Despite the absence of anything sexually explicit, there was no question for Comstock that such images violated the Comstock Act, which forbade “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” books, pictures, etc., as well as “any publication of an indecent character.” Although Comstock recorded several mass seizures of this book in 1895, close to two dozen library collections today hold Le Nu; the University of Michigan, in collaboration with Google, has even posted a copy, dirty pictures and all, online. Another great example of a censored illustrated book entered in the Library of Congress is an 1874 version of Balzac’s bawdy Droll Stories (fig. 4).

Although many libraries play host to smutty books (as Comstock would have seen them), censored circulars and pamphlets are harder to find, because they often are not catalogued individually in online databases. This is where reference librarians, inventive thinking, and determination are a must. In this regard, my luckiest smut-hunting discovery has been the “Case Files of Investigations” of the Bureau of the Chief Inspector, which form part of the Records of the Post Office Department housed in the National Archives.

I got a tip from a reference specialist at the U.S. Postal Service Library in Washington, D.C., that inspectors sent reports to the postmaster general about each case they prosecuted. At the National Archives, the librarian in charge of civil records referred me to a “finding aid” which consisted of an old binder with cryptic and extremely general descriptions of the collection. I started by ordering an index of postal defendants, which did include some prominent Comstock victims, seemingly paired with a number for the box the report was in. After two days of “pulled” boxes that did not have the files I needed, I realized that the index cards were for an older filing system. The current organization was entirely chronological, so I needed to order boxes by date and not number. But what dates? After looking through the reports, it became clear that the date of arrest was the key. So, I went back to the blotters in the Library of Congress, wrote down the dates of arrest of interesting-sounding cases, and voila! Boxes that seem scarcely to have been looked at in the past century yielded Comstock’s reports, often hand-written and filled with editorializing about the defendants, judges, etc. Some files even contain copies of the evidence seized, such as a circular advertising “Art portfolios of full page Photo Prints of Nude Female Figures … reproduced from paintings of the most Beautiful Living Models in existence” (fig. 5). Despite the advertised claim that these books were “especially for the use of Artists and Art Students,” Comstock refused to concede their professional necessity.

Self-reported “medical” necessities also failed to escape the net of postal inspectors. Dr. Chalco’s Magnetic Developer promised “a veritable boon to mankind” (fig. 6). A customer’s testimonial claimed that after only a few days “to my surprise I find my organs to have been enlarged to nearly twice their former size.” Whether or not the claim was accurate, the advertisement nonetheless resulted in a $100 fine.

Throughout the movie National Treasure, the outcome of the treasure hunt is obvious: the dashing and adventurous historian will obtain the beautiful curator, as well as the treasures of the Ancient World. It makes sense to consider what the correlate reward is in a pursuit of our national incinerator-fodder. In his day, Anthony Comstock was a household name, signifying an older order of values. H. L. Menken described him in A Book of Prefaces (1917) as “more than the greatest Puritan gladiator of his time; he was the Copernicus of quite a new art and science.” He was anti-lust, anti-immigration, anti-gambling, anti-drinking, anti-birth control, and he believed that government should regulate morality by any means necessary. Because his raids were so voluminous and well-publicized (even when they weren’t successful), his aesthetics served for forty years as the national line between virtue and vice. Recovery and analysis of where that line was drawn in historical periods provides an indispensable context for understanding the bright lines of our own day, particularly as they are drawn differently within micro-communities defined by diverse ideologies, demographic characteristics, and regional variations.

Uncovering the materials Comstock tried so hard to bury is informative in another sense, for whatever idea we may have that Victorians chose virtue far more often than ourselves is undermined by the sheer volume of smut Comstock rounded up. The trash he tried to bury helps us understand the choices Americans made in those facets of their lives they did not often present for display. As in the case of Dr. Chalco’s magnetic developer, we may find more commonality with our predecessors than we might expect—in other words, Comstock’s story is a great reminder that some things really never change.

The long-term outcome of Comstock’s efforts surely would have disappointed him. Who would deny that his battle to save our national souls from the dangers of obscenity was utterly lost? And yet, his career did have some profound and lasting results. The list of prominent individuals Comstock prosecuted reads like a Who’s Who of America’s post-Civil War radicals, including Victoria Woodhull, Ezra Heywood, Moses Harman, D. M. Bennett, E. B. Foote, Emma Goldman, and Margaret Sanger (via her husband, William). These individuals seldom agreed on the fine points of free love, anarchism, conjugal relations, contraceptive methods, eugenics, or women’s suffrage. However, there was one creed on which they did agree:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Comstock galvanized these figures, and many more, to form organizations of common purpose to defeat him, and ultimately, their legacy far outshone his. No figure in American history has brought the significance and survival of the First Amendment as much into question as Anthony Comstock. Our constitution is, of course, our true National Treasure. Any search that helps us better understand the wisdom of that document is worthwhile, even if it compels us to examine our nation’s most disreputable waste.

Further Reading:

The most comprehensive biography of Anthony Comstock is Heywood Campbell Broun and Margaret Leech, Anthony Comstock, Roundsman of the Lord (New York, 1927); for a more recent and focused study of his efforts, read Nicola Kay Beisel, Imperiled Innocents: Anthony Comstock and Family Reproduction in Victorian America (Princeton, 1997). Two excellent studies regarding the Woodhull case are: Amanda Frisken, Victoria Woodhull’s Sexual Revolution: Political Theater and the Popular Press in Nineteenth-Century America (Philadelphia, 2004), and Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, “Victoria Woodhull, Anthony Comstock, and Conflict over Sex in the United States in the 1870s,” The Journal of American History 87:2 (September 2000): 403-34. An excellent recent biography of Henry Ward Beecher is Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America (New York, 2006). Two relevant dissertations also are worth excavating: Comstock’s targeting of immigrant groups is well tabulated and analyzed in Richard Christian Johnson’s “Anthony Comstock: Reform, Vice, and the American Way” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 1973), and Elizabeth Bainum Hovey analyzes the evolution of obscenity law during Comstock’s years in “Stamping Out Smut: The Enforcement of Obscenity Laws, 1872—1915” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1998).

This article originally appeared in issue 11.1 (October, 2010).

Amy Werbel is professor of fine arts at Saint Michael’s College, Colchester, Vermont. She is currently completing a book, American Visual Culture during the Reign of Anthony Comstock. Her previous scholarship includes Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century America (2007).