Straining to hear black voices in the records available to study slavery in early America, historians have rarely noted how difficult it is to see black faces. Even those figures who were written about relatively extensively at the time are more faceless than they are voiceless in surviving records. A case in point is Denmark Vesey, the leader in 1822 of the largest slave rebellion conspiracy in American history and arguably the most fully documented black person in the South prior to the explosive emergence of Nat Turner in 1831. More than a century and a half after the conspiracy was uncovered and its leaders executed, a number of black Charlestonians sought to memorialize Vesey’s leadership with a portrait. The artist, however, soon discovered that there was absolutely no indication in extant records of what he looked like. Unlike the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, Toussaint Louverture and Henri Christophe, there were no portraits of Vesey, which is somewhat ironic in that Vesey may have been born in Haiti and had planned to escape to that island nation as part of his plan of rebellion. The solution the artist settled on was to draw Vesey from behind as he spoke to a large audience from a raised platform.

As regrettable as dilemmas of this sort are we should not be surprised by them. Or should we? The images that have come down to us from the colonial era, particularly the colonial South, almost uniformly reflect a slave-owning perspective. Their ethnographic value is minimal at best, whether viewed in terms of what they illustrate about slavery or slave life, but especially the latter. Even when black figures appear in a painting or drawing, as when someone like Vesey appeared in the written record, we feel as though some important part of their person is missing. In fact, what is absent is any sense of their individuality. The subjective presence of blacks is so uniformly missing from the visual record created by (or for) the slave-owning community that its absence could not have been unintended. But why? Why is there not a more detailed visual record of slavery and even slave life in early America?

Generally speaking the visual record is not as barren in other New World slave societies. We have nothing comparable, for example, to the painting by Dirk Valkenburg, entitled Slave Play on Dombi Plantation (Suriname) .

For its time (1707), Dirk Valkenburg’s painting, Slave Play on Dombi Plantation, is unparalleled as an observation of slave life in the Americas. Although exceptional, its ethnographic value is not unique in the pictorial record that has survived from the first two centuries of widespread European colonization in the Caribbean, starting in the early seventeenth century. However, nothing even remotely comparable to it survives from colonial America. The closest approximation is The Old Plantation, a painting that is thematically similar to Valkenburg’s but crude in most respects by comparison.] Sensuous in its lighting–indeed, almost cinematic in its effect–the painting shows us a large group of mostly bare-breasted, African-born slaves preparing to participate in a wintidance. Away from the watchful eye of slave owners and overseers, the subjects of the painting are observed simply enjoying each other’s company. Such everyday pleasantries may seem unremarkable. Yet when compared to the pictorial record we have of the earliest century and a half of our slave past, it is nothing less than extraordinary.

Such regional disparatiesdisparities in the visual record of slavery pose more questions than they answer. Without trying to explain these variations I would like to explore why the pictoralpictorial record of colonial American slavery is so relatively barren and thus what the omissions tell us about the experience of being black in early America. I would then also like to suggest why the answer has eluded us, arguing, with the help of two very rare and anomalous paintings, that the reason has to do with how we have looked at the record and for what.

Typical of the images of slavery that have survived from colonial and early national America (primarily the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries) is the portrait by John-Baptiste Paon of the marquis de Lafayette, a work that was drawn to commemorate the Siege of Yorktown (fig. 1).

This portrait by John-Bapiste Paon of the marquis de Lafayette to commemorate the Siege of Yorktown is typical of the portraiture that has come down to us from colonial America, especially the colonial South. Less well known than similar paintings of George Washington in which he is attended by his longtime body servant Billie Lee, the portrait of General Lafayette typifies the pictorial record of slavery in which black subjects are used as decorative objects to accentuate each painting’s main focus, an elite white male or members of his family.] In the portrait, a black man, James Armistead, attends Lafayette. Although both were Revolutionary heroes, Armistead was also the property of a Virginia planter named William Armistead. After the war Lafayette would praise his black orderly for his industrious and faithful service as a spy. “He perfectly acquitted himself,” according to Lafayette, “with . . . important commissions . . . [and was] entitled to every reward his situation [his owner and the American government willing] could admit of.” This testimony apparently helped in securing Armistead’s freedom after the war. No doubt that is why Armistead later added Lafayette to his name.

The marquis, naturally, is the central focus of Paon’s portrait. General of the Continental Army, he is dressed appropriately in the painting. Ralph Ellison, writing in 1974 for a bicentennial project, noted that “the young French aristocrat” is shown pointing “with enigmatic expression” toward Yorktown. He is seen standing “hatless, his powdered wig showing white against a cloudy sky in which a slight rift promises sunny days ahead.” Ellison’s description of how James Armistead is depicted in Paon’s portrait is worth quoting because it so clearly characterizes the pattern that can be found in most such portraits. As was customary, Paon, according to Ellison, “intensified the hierarchical, master-servant symbolism of his composition by rendering the black orderly’s features so abstract, stylized, and shadowy that the viewer’s attention is drawn not to the individuality of Armistead’s features but to the theatrical splendor of his costume.” While Armistead’s face remained a kind of blank, his overall appearance was rendered flamboyantly exotic. Indeed, according to Ellison, “the Florentine splendor of his garb” was such that it added “glamour and mystery even to Lafayette.”

Unlike poor whites, or non-elite whites in general, blacks frequently appear in the pictorial record that has survived from the colonial South, but only in the ornamental or decorative form described by Ellison: as objects whose function was not only to serve their owners, but to enhance their self-image. Similar images of blacks also survive in the much larger and more diverse written record left to history by the slave-owning community. Whether in plantation records, newspapers, court or legislative records, blacks appear almost exclusively as objects to be counted, contested, controlled, and in general kept track of. As rich as many of those sources are regarding slavery in Britain’s North American colonies, references to blacks as individuals in their own right occur only parenthetically as amused, exasperated, or condensing asides. Unless, of course, slaves managed to force their way into the records by rebelling or planning to or by some other equally threatening behavior.

Thus, like the portrait of Lafayette in which James Armistead appears, blacks are frequently present in surviving documents but almost always as objects of concern rather than as self-reflecting subjects. Portraits like Paon’s do not make blacks more visible as subjects. But they do illustrate for us a pattern of representation that is so ubiquitous in surviving written documents that it is easy to overlook. On its own, such an image merely suggests yet another example of slave-owning conceit or planter-class self-indulgence. However, when overlaid on the written record, portraits like Paon’s re-enact for us a critical feature of enslavement.

In order to survive in early America blacks had to accept the self-denying identity, Negro. Those who refused to do so did not survive. It was that simple and that terrifying. The process was often a brutal one, driven by physical violence and torture. Brutality was a means to an end, however, not the preferred way of achieving it. Slavery as an institution, representing the economic foundation upon which much of colonial antebellum America was grounded, could not be run as a prison camp, not day in, day out for more than two and a half centuries. Instead, physical violence was used to create a climate of terror in which the necessity of becoming a Negro, or at least convincingly pretending to do so, became a part of the slaves’ intuitive understanding of what it meant to survive, a, a self-perpetuating means of self-enslavement. The way blacks were visually portrayed, and the ways in which they were forced to project in daily life the same lack of subjectivity that comes through in these rare portraits, demonstrate this unrelenting assault on the slave’s sense of self. Unintentionally, portrait painters like Paon provided us with a glimpse of that process as it was experienced by a few survivors. The fact that Armistead, through his own initiative, was a privileged survivor only heightens the effect.

By striking contrast two very different paintings help reinforce our understanding of the process of self-enslavement by giving us a rare view of aspects of black life that are otherwise missing from the records kept by the slave-owning community. One of them suggests the terror that permeated slave life, while the other, a pale reflection of Valkenburg’s Slave Play, illustrates a scene from the private lives of a few black slaves. These two paintings reflect another pattern of representation that can be easily identified in the written record: the unique importance of non-American eyes and pens. Only visitors to the region left written descriptions of slavery and black life that could be termed ethnographically valuable. The same is true of the visual record that has survived. French architect and engineer Benjamin Henry Latrobe composed by far the most valuable collection of drawings of blacks in the American South up to the time of his visit during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. His sketches and watercolors give us glimpses of daily workaday or leisurely life in the region (primary the upper South) that are unparalleled, a sense of place that is only surpassed by the drawings of John White, who documented the flora and fauna and aspects of native life on North Carolina’s outer banks in the late sixteenth century. Latrobe’s sketches and watercolors, however, are not so much about blacks as they are about blacks as part of the social and material landscape he was attempting to record and about how that landscape was made distinctive by their presence.

We do not know if the two anomalous paintings that stand out so glaringly among the other visual images that have survived from the colonial South were painted by visitors to the region like Latrobe because both are surrounded in mystery. However, they clearly reflect the pattern of representation that Latrobe’s drawings serve so well to illustrate. In fact, they offer a much more concentrated view of blacks and their lives than Latrobe’s drawings offer. Both appear to date from the early national period–that liminal moment in American history that both links and divides its colonial beginnings to and from its national future. Though neither is dated or signed, the clothing worn by the subjects in the two paintings seems to reflect a colonial rather than an antebellum setting.

One of the two canvases captures, or attempts to capture, a social setting exclusive to black slaves. The other is divided into two scenes, one showing a white man kissing a black woman, apparently against her will, the other a white man whipping a black man (fig. 2).

As if to mimic the tendency of most Americans, including the Founding Fathers, to say as little as possible about slavery, and either to deny or avoid discussing its brutality, the painting, Virginian Luxuries appears anonymously (undated and unsigned) on the back or unseen side of another painting.] This two-part picture is hidden on the back of another painting. Written in fairly large letters at the bottom of the painting is its title, Virginian Luxuries, suggesting the scene’s location as well as a critical perspective on slavery.

By contrast there is no hint of where the gathering depicted in the other painting takes place, nor is there any indication of what motivated the painting (fig. 3).

Few colonists of early America or citizens of the nation’s early national period left descriptions of black life that could be termed ethnographically useful, even in those areas where it would have been impossible to avoid close contact with blacks. Only visitors to America left descriptions comparable to the painting,The Old Plantation, an undated and unsigned picture found in Columbia, South Carolina. The paper on which it was drawn can be dated between 1777 and 1794 by the watermark of the paper maker, which tends to confirm speculation by historians that it reflects a late eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century scene. The scene itself is believed to have been observed on a plantation somewhere between Charleston and Orangeburg, South Carolina.] Was it curiosity, contempt, amusement, sympathy? And unlike Virginian Luxuries no title originally appeared on the other mysterious painting when it was found. It was subsequently named The Old Plantation rather than something more specific to its content.

Both canvases are worth puzzling over because they are so rare. Both, in fact, are unique records of their kind, visually depicting experiences that invite the viewer to consider the self-reflective dimension of the life-worlds the artists attempted to portray. We can either lament that there are so few such paintings, reflecting a similar poverty in the written record, or we can learn from the perspective they reflect as much as from what they describe. Slavery was lived, not merely imposed and endured, accommodated and resisted. It was experienced, in ways these paintings (and the others I will briefly discuss below) compel us to explore. What was the nature of the slaves’ lived or felt experience? What forms did its expression take? What bases for self-affirmation were slaves able to establish and maintain, and how were they expressed? If they resisted becoming Negroes, as we know the vast majority of them did, what was their sense of themselves as individuals–or collectively as families and communities? And how, where and when, was this sense of self expressed?

Of course asking such questions is one thing, answering them is quite another. But as daunting as the challenge seems, it may not be beyond us. It is possible, for instance, to replicate Latrobe’s drawings of blacks, using the available written documents. It would require considerable effort but it could be done. It is even possible that we could use written sources to flesh out the quotidian world sketched by Latrobe–including the atmospherics that his drawings evoke–even more fully than he was able to do. But in order to do so historians would have to be willing to think of the past more in terms of its experiential content than solely in terms of its social and material structure.

Snapshots of black life can frequently be found in reports of events that are not directly related to blacks or slavery, events like natural disasters or other curious phenomena. These glimpses of slave life are rarely as detailed as in the two mysterious paintings but they are much more numerous and are occasionally susceptible to enlargement. Thus, if we look at the records that the slave-owning community kept (especially its parenthetical and inadvertent references) in the way that Latrobe and other visitors to the region observed the landscape they traveled through, perhaps we will begin to see more of what blacks experienced. Just as Vesey’s biography–his life not his face–has become more visible the more creatively and expansively writers have looked for it. Black subjects, even those that have been cast in shadow or objectified beyond recognition, can still be seen as subjects if we look closely and if we ask the questions that these paintings encourage us to pursue, even those that objectify the black presence.

Perhaps nowhere are such questions and the myriad issues related to them more urgently felt than when we look at the few portraits of blacks, including black Southerners, that begin to appear in late Revolutionary and early national America, during a time marked by the emergence of a transatlantic antislavery movement. These images are of two sorts, those that might be termed heroic by emphasizing the dignity or status of the subject, and those that are perhaps best described as character studies, regardless of their intent. When we look at the extremely rare number of paintings in the latter group–the studio study by John Singleton Copley of the anonymous black man featured in his masterpiece, Watson and the Shark (1778), or Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of the elderly, African-bornYarrow Mamout (1819)–we rarely think of either subject as an object in relation to others but rather as self-aware individuals. We strain to think what they are thinking and to know them better. We recognize that they are black and assume their association with slavery based on their color, but are quickly drawn beyond that recognition to an interest in their person, to the feelings and experiences that give character to their faces.

The heroic portraits include those by Joshua Johnson, the free black limner who was in great demand as a portrait artist in and around his native Baltimore during the early national period. Most of his portraits were of whites, including family portraits, but a handful were of free blacks. His African American subjects no less than his Anglo-American ones reflect an inner dignity as a natural characteristic, reducing their color to an incidental feature, not insignificant but not determinant either.

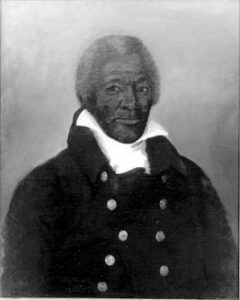

The same was true, according to Ellison, of the heroic portrait that was made of James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin in 1818 (fig. 4).

By contrast to paintings like Paon’s portrait of Lafayette, the portrait of James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin focuses in heroic terms on its black subject. Armistead Lafayette, shown in the background in Paon’s portrait, distinguished himself as a spy for the American cause during the war and was subsequently freed, on General Lafayette’s recommendation, for his service.] Ellison noted that Martin, who was born in Ireland and had only recently arrived in Virginia when his portrait of James Armistead Lafayette was completed, portrayed the black Lafayette as a proud and dignified person. He appears “with his highly individualized features forcefully drawn, a dark, ruggedly handsome man looking out at the viewer with quizzical expression.” No longer attired in the exotic livery that so marked his appearance in Paon’s portrait, Martin’s Lafayette is wearing his blue military coat, the buttons of which Ellison noted were embossed with American eagles. The portrait, Ellison concluded, portrayed a man “[a]sserting an individual identity.”

Of course it is not unusual for artists to search for telling details, a “quizzical expression” that can illuminate a subject or event. Yet it remains extremely rare to find historians of slavery in early America who look for those sorts of self-expressive or self-reflective attributes, or more generally who seek to study lived experience as such. It is possible that such an interest cannot be meaningfully realized, given the sources available to us, but how will we know until we try? And aren’t we obligated to make the effort? Otherwise, to paraphrase James Baldwin, how will we ever manage to get beyond “questions of color” in order to engage those “graver questions of self” that were so important to the survival of blacks in early America?

Further Reading:

For studies that discuss a number of the representational issues raised in the text see Albert Boime, The Art of Exclusion: Representing Blacks in the Nineteenth Century (Washington, D.C., 1990); Guy C. McElroy, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art 1710-1940 (San Francisco, 1990); Allison Blakely, Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of Racial Imagery in a Modern Society (Bloomington, Ind., 1993); and Kim Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, N.Y., 1995). My own study, The Punished Self: Surviving Slavery in the Colonial South (Ithaca, N.Y., 2001), is also relevant. The controversy surrounding the memorial to Vesey is discussed in David Robertson, Denmark Vesey: The Buried History of America’s Largest Slave Rebellion and the Man Who Led It (New York, 1999). Also see Douglas R. Egerton, He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey (Madison, Wisc., 1999) for a related discussion. A brief description of Valkenburg’s painting can be found on the dust jacket of Robin Blackburn’s The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern 1492-1800 (New York, 1997); see also the reproduction in Richard D. E. Burton, Afro-Creole: Power, Opposition, and Play in the Caribbean (Ithaca, N.Y., 1997). Ellison’s discussion of Paon’s portrait of Lafayette and Martin’s portrait of James Armistead Lafayette is in his essay, “James Armistead Lafayette,” in The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (New York, 1995), 399-403. On other images of James Armistead Lafayette, see Fritz Hirschfeld, George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal (Columbia, Mo., 1997). On Martin, see L. Moody Simms Jr., “John Blennerhassett Martin, William Garl Brown, and Flavius James Fisher: Three Nineteenth-Century Virginia Portraitists,” in Virginia Cavalcade (Autumn 1975): 72-79. For a close analysis of The Old Plantation see Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1982). Virginia Luxuries is reproduced on the cover of Mechal Sobel, Teach Me Dreams: The Search for Self in the Revolutionary Era (Princeton, N.J., 2000) and in Kathleen M. Brown’s Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill, 1996). The drawings made reference to in the text are reproduced in Edward C. Carter II, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Series I, Journals: The Virginia Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1795-1798 (New Haven, 1977). Reproductions of Joshua Johnson’s work can be found in Carolyn J. Weekley, Stiles Tuttle Colwill, with Leroy Graham and Mary Ellen Hayward, Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter (Exhibition Catalog published by the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the Maryland Historical Society, and the Museum and Library of Maryland History, 1987).

This article originally appeared in issue 1.4 (July, 2001).

Alex Bontemps teaches African American history at Dartmouth College. His book, The Punished Self: Surviving Slavery in the Colonial South (Ithaca, N.Y., 2001), was recently published by Cornell University Press.