Sponsored by the Chipstone Foundation

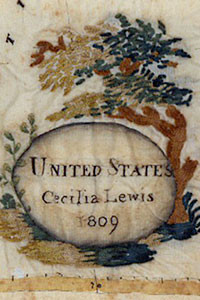

A delicately woven ivory silk map, embroidered in the first years of the nineteenth century, offers lessons about how early Americans envisioned the future of the new nation. The fabric bears a map of the United States outlined in couched chenille, its margins only slightly torn and frayed (fig. 1). Though slightly stained and bearing minor holes, the fabric is clean and intact, as are most of the stitches upon it. In the lower right, an oval cartouche embraced by a richly embroidered tree identifies the maker as one Cecilia Lewis, and gives the year in which she stitched the map: 1809. One of the rarest extant American cartographic samplers, this map of the United States was embroidered by eighteen-year-old Cecilia Goold Lewis, a pupil at the Pleasant Valley boarding school on the banks of the Hudson River near Poughkeepsie, New York. The map is significant not only for its primary subject—the young United States—but also for its inclusion of Native American tribes (figs. 1a and 1b). And unlike other map samplers that are now held in collections on the eastern seaboard, where they were made, this map eventually made the long journey with its maker to the land of the “Outigamis” and “Chipawas” west of the Great Lakes. What can the sampler tell us about nineteenth-century culture and life in the United States, and, conversely, in what ways might historical records illuminate the object and the life of its maker?

Embodying a rich and storied history, Lewis’s map transcends its own physical materiality beyond her skill with a needle. Government census and genealogical records can help us flesh out the temporal and geographic context of the embroiderer, granddaughter of Francis Lewis, a uniform supplier and signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Elizabeth Annesley Lewis, who was held captive by the British during the Revolutionary War. Cecilia was born in the village of Flushing, Long Island, in New York on January 12, 1791, to Elizabeth Ludlow and Francis Lewis Jr., a businessman like his father. In the crucible of burgeoning revolution, her Tory maternal grandparents had vigorously objected to the marriage of their daughter to a young man whose father “would certainly be hung,” according to one history of Flushing. Given the family’s active political participation in the birth of the new nation, a sampler bearing an image of the United States might have had particular familial meaning above and beyond its value as a geography exercise.

What can the sampler tell us about nineteenth-century culture and life in the United States?

A tint of blue paint along the raised, embroidered shorelines enhances the low relief of the landmass, diffusing out to greater depths into the Atlantic and within each of the Great Lakes. Hair-fine black silk thread spells out the names of places and peoples. Guidelines in ink peek out below loosened or missing stitches and delineate the finely gridded graticule that subtly undergirds the picture plane. Couched silk chenille lines in earthen tones invite the viewer to touch, to feel one’s way into the far reaches of the continental interior along the courses of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and to follow the horizontally cast boundaries of the central states. The visual logic of engraved maps directs the eye to enter and travel by way of printed lines—or, in the case of the embroidered map, by what path the needle might next pursue. Though the masthead-like form of Maine pushes northeasterly, the ribbon of words loosely paralleling the national form—Atlantic Ocean, Lower Canada, Upper Canada—reins the eye back into the body of the landmass. The seamstress penetrated the surface of her imagined silken countryside to reconstruct a nation in miniature, not unlike the farmers whose plows cut lines into unturned earth at the local level, each a participatory exercise in patriotism. Like other American maps, Lewis’s embroidery encouraged viewers to read cartographic pictures of their nation from right to left, or east to west, the direction in which the country would expand. Embedded within the map lay a perceptual friction between text read from left to right, as habituated by European writing systems, and the visual scanning of westward-bound cartographic expansion.

School

Needle arts historian Betty Ring has linked the map stylistically to others made by students at the Pleasant Valley School, an establishment operated by three Quaker women, two of whom had recently migrated from England. Founders Ann Shipley and her niece Agnes Dean brought to America their knowledge of embroidering maps, already a common practice in eighteenth-century imperial Britain. The map samplers made at their school resembled those made at Esther Tuke’s boarding school in York, England, which were similarly worked “upon white silk … in chenille.” (Ann Shipley likely knew the headmistress and her school, which listed two other Shipley girls in attendance in 1802.) The cartouche embroidery in the Lewis sampler exemplifies the style and form found in other Pleasant Valley embroidered maps, as does the stitching of boundaries and tinted coastlines. Pupil Mary M. Franklin, for example, constructed a larger and more elaborate map of the western hemisphere (held at the Winterthur Museum), employing the same colors and types of stitches on an off-white silk background (fig. 2). The lushly articulated trees and flowers surrounding both cartouches are of the same technique and form, and each embroiderer paid careful attention to lines of longitude and latitude. With extra-heavy embroidery Franklin highlighted the configuration of the United States within the North American continent, the same national boundaries appearing in the Lewis sampler. Both maps reflect the visual acuity and dexterity of youthful seamstresses who were already advanced in needlework.

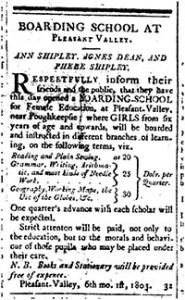

The new Pleasant Valley School advertised in the June 7, 1803, issue of The Poughkeepsie Journal, & Constitutional Republican, offering instruction in “most kinds of Needle Work …” including “working maps” (fig. 3):

Boarding School at

Pleasant Valley

Ann Shipley, Agnes Dean, and

Phebe Shipley

Respectfully inform their friends and the public, that they

have this day opened a BOARDING SCHOOL for Female

Education, at Pleasant-Valley, near Poughkeepsie; where

GIRLS from six of age and upwards, will be boarded

and instructed in different branches of learning, on the fol-

lowing terms, viz.

Reading and Plain Sewing at 20 Dols. Per Quarter

Grammar, Writing, Arithmetic, and most

kinds of Needle Work… 25 ” “

Geography, Working Maps, the

Use of the Globes &c. 30 ” “

One quarter’s advance with each scholar will be expected.

Strict attention will be paid, not only to the education, but

to the morals and behavior of those pupils who may be

placed under their care.

N. B. Books and Stationery will be provided free of expense.

Pleasant-Valley, 6th mo. 1St, 1803.

Furthermore, the announcement explicitly emphasized geography as essential to the well-rounded education of young women who might someday nurture into adulthood a society of moral American citizens. As Martin Brückner has written, geographic literacy and map skills in the early republic came to be understood as vital to the education of young Americans in a new democratic nation where territorial expansion and the cohesion of distinct states were imperative to national success. Through the creative configuration of lines and shapes upon a two-dimensional surface, maps of the United States instilled—visually and aesthetically—the notion of a collective national identity.

Embroidered maps and globes were among the first cartographic objects to be made and used in the classroom in the United States, though only a limited number of establishments offered such instruction. Those families who were fortunate enough to have a daughter attending such a school typically displayed map samplers as decorative household items alongside other fancy needlework to showcase a young lady’s educational and cultural accomplishments, sometimes for the benefit of potential suitors. Female education in the American colonies and early republic customarily included instruction in needlework, from plain sewing to more elaborate needle arts; even when girls and boys studied side by side in the same schools, girls typically received sewing and embroidery lessons while boys learned surveying, a skill understood as indispensable in a nation of new landowners and expanding territories.

After students had spent long hours constructing their maps—having carefully fingered every textured line—the names and shapes of each political unit would remain entrenched in both mental and muscle memory. As the nineteenth century progressed, American youth increasingly learned their geographies experientially through three-dimensional cartographic objects that capitalized upon a multi-pronged engagement of the students’ senses, unlike the nearly exclusive reliance on memorization of the written word in previous centuries (more of these pedagogical objects can be seen in the accompanying image gallery. The practice of sewing maps waned by the 1840s with the normalization of female education, as girls joined their male counterparts in drawing maps on paper.

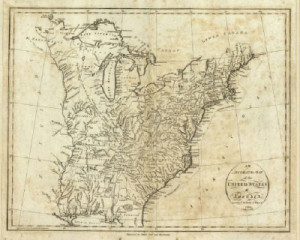

Far less common than in England, where eighteenth and early nineteenth-century map publishers circulated patterns in magazines and sold pre-printed fabric to be worked by fashionable ladies, nineteenth-century schoolgirl maps in the United States were largely copied onto fabric either by the student or instructor. Lewis’s map does not, in fact, reflect the state of the union in 1809, but instead matches a historic map drawn according to the Treaty of Peace of 1783, which later appeared in an atlas published in 1796 (fig. 4). Distortions in the atlas map, such as the shapes of Michigan and Lake Superior, are replicated in the Lewis map, and the spellings of Indian and place names are also copied letter for letter. East and West Florida are divided, and Alabama and Mississippi have not yet been defined (fig. 4a). Organized states do not yet appear north and west of Pennsylvania on either map. Perhaps more remarkably, the embroiderer has strictly adhered to the curvature and placement of the longitudinal and latitudinal lines along the numbered border, which demonstrates a comprehension of cartography that transcended the merely decorative. That Lewis or her teacher chose a map of the newly independent United States suggests that the exercise may have been part of a history lesson, or perhaps influenced by her own family’s illustrious participation in that history.

The Journey West

As is often the case in the lifespan of objects, the sampler survived long beyond its maker, passing from the hands of one daughter to the next through the next three generations. In 1813, Lewis had married Samuel Carman, a physician whose family lived near her boarding school. In the early 1850s—four decades after making the sampler—Lewis and her family moved to Madison, Wisconsin, a fledgling town in a region identified on her sampler as the domain of the “Outigamis” and “Chipawas.” The map ostensibly made the westward journey to Wisconsin with Lewis sometime between 1850, when the Carmans were recorded as living in Ridgeway, New York, and 1854, when the family appeared on the member list of Madison’s First Congregational Church. The object materially traced Lewis’s own cross-country emigration: like its maker, the silken rectangle bearing an obsolete image of the early republic had weathered four long decades and over a thousand miles of travel when it arrived in the Old Northwest Territory.

At the time Lewis executed her map, Thomas Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery had only recently returned from the search for a Pacific route to Asia, and national lawmakers remained skeptical about the feasibility of stretching and maintaining federal oversight over a vast and distant continental interior (a territory largely absent from Lewis’s map). Whereas the openness of the territory east of the “Mississipi” River invites the eye westward, the heavily embroidered river functions visually and tangibly as a vertical border, bringing the viewer’s eyes back into the space of the map. Only at the most northwesterly source of the river, signaled by the pointed western tip of Lake Superior, does one find a visual outlet and the possibility, perhaps a lure, to venture further into an unarticulated and largely unknown interior.

The Lewis sampler, based on a 1783 map, did not include the vast lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which had doubled the size of the nation—here the letters of the word “Louisiana” lie vertically parallel to the Mississippi River, thereby constructing another, yet more porous, visual boundary. Indian names sprawled across the region north and west of the Ohio River spell out a vast but vague and unorganized native presence. The absence of engraved political borders between indigenous nations suggests to the viewer a lack of knowledge on the part of the cartographer from whom the embroiderer received the information, but it might also be read as a silent mediation that erases actual British, French, and Indian presence. Furthermore, the space also communicates a kind of geographic emptiness that might be filled by the reader’s imagination, as well as the notion that indigenous peoples had little official claim over this uncharted territory—territory that Native people had occupied for millennia and about which they had sophisticated geographic knowledge.

As the nation rapidly expanded in the following decades, many Americans came to perceive the continent itself as a vast fabric upon which the technologies of steam power, telegraph, and rail lines constituted the threads that bound the nation together. Contemporaneous writers observed that the iron rails and wooden ties connecting distant populations “stitched” one region to another, as did the printed hatched lines of rail routes on maps. By compositionally correlating the right and left picture borders with the east and west coordinates of the American map, artists who imaged westward emigration after mid-century routinely treated the picture plane as a cartographic surface upon which to inscribe the ideologies of Manifest Destiny, the Euro-American imperative to populate the continent. This compositional trope coincided with a golden era in United States cartography and the corresponding mass democratic dissemination of printed maps that encouraged many citizens to think of the nation and the picture plane as a map. For example, in his 1860 painting On the Road, Pennsylvania artist Thomas P. Otter contrasted the streamlined, sun-kissed trajectory of rail travel with the dirt-lined, winding route taken by a lumbering Conestoga wagon (fig. 5). (The painting was likely commissioned by Matthias W. Baldwin and Joseph H. Harrison, locomotive manufacturers for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, who would have had a vested interest in showcasing the sleek efficiency of modern railroad technology.) In the context of the American cartographic boom, Otter’s small slice of road might be understood as a fragmentary piece of a longer itinerary on contemporaneous railroad maps, some of which featured small train icons crawling along the engraved routes. Similarly, the stone mile marker in the foreground identifies Otter as the image’s maker, not wholly unlike the role played by a cartouche on a map.

At mid-century the nation possessed contiguous land extending westward to the Pacific Ocean, and romantic tales of the Oregon Trail and the California Gold Rush dominated the American imaginary. But in actuality more people—in the tens of thousands—were moving into and taking up residence in the Mississippi Valley. Like so many other Yankees, the extended Carman family moved westward in search of new possibilities, and similarly, may have used one of the many portable pocket guides, such as Colton’s Western Tourist and Emigrant’s Guide, which offered geographical statistics, travel advice, large fold-out maps, and appealing inducements in the form of cheap land and agricultural promise (fig. 6).

Most emigrants came to Wisconsin through the port of Milwaukee by way of Great Lakes steamers and the Erie Canal, but the Carmans may have opted for rail travel. It would not have been so straightforward as suggested by Otter’s picture, however, given that there were no direct rail lines to Chicago—only a rhizomatic web of shorter connections averaging nineteen miles between hinterland towns on non-standardized gauges. One young man arriving in Milwaukee from Cleveland at the time, for example, transferred through four different railroads, with extended intermediary stretches by stage coach. An 1851 railroad map illustrates the tangled arteries of main lines and their “tributaries” that emigrants had to navigate (figs. 7 and 7a). The horizontality of the map, nevertheless, pulls the eye visually along linear branches that reach left/westward. Wisconsin first introduced rail travel in 1850 along an unassuming ten-mile stretch from Milwaukee toward Waukesha; therefore, the Carmans would have had to traverse many miles by stage, a jolting affair over rough “newborn” roads that, in the words of Frederika Bremer en route to Madison in 1849, were “no roads at all.” The family, however, would have found a growing town of about 3,000—as well as many of the amenities they needed for living—where only eighteen log cabins had stood the decade before.

Wisconsin

On Lewis’s map, bare ivory silk fills the empty spaces between boundaries, but by the time the Carmans emigrated, new maps reflected the work of thousands of surveyors who had dissected and subdivided Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and the southern part of Wisconsin into rectilinear counties, townships, and sections according to the Land Ordinance of 1785, the Jeffersonian mandate for organizing unmeasured land for new property ownership. The result was a filled-in geometric pattern that represented to many Euro-Americans the rich potential for further growth and opportunity in an already organized, well-ordered land. Maps of these young states, like the large fold-out version that accompanied the J. H. Colton emigrant’s guide, resembled patchwork quilts in four colors that easily accommodated the addition of ever more rectangles (figs. 8 and 8a). Wisconsin won statehood in 1848 and, like other Midwestern states, witnessed explosive population growth—from 31,000 in 1840 to 305,000 by 1850. The stark contrast between these officially printed maps from the 1850s and the one made by Lewis reveals the massive changes taking place in the land of the “Outigamis” and “Chipawas” in just four decades. One might imagine that an expansive gridded blanket had been laid over the open spaces of the Lewis sampler.

Identified in the upper section of the sampler, the Chippewas (“Chipawas”)—also known as the Ojibwe peoples of the upper Great Lakes—formed an Anishinaabe alliance that included the Odawas (“Utawas” or Ottawas). The Meskwaki or Fox peoples, called the Outagamies in the Anishinaabe language, allied themselves with the Sauks farther south. (The obsolete name survives on maps of Wisconsin in the form of Outagamie County.) But the Dakota, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee peoples also claimed large portions of the region as their homes. Lewis had placed the “Nadowessis,” a Dakota tribe, in the far north. Indigenous presence in Wisconsin was never static and, in fact, constituted a complex, fluid web of intercultural alliances, interactions, and negotiations as large numbers of refugees from eastern tribes had flooded the region earlier, pushed westward by Euro-American settlement and the powerful Iroquois. In other words, change marked the lands west of Lake Michigan long before surveyors’ gridded maps made visible the influx of white American settlers. Lewis’s map does not address this complexity, nor does it mark the presence of thousands of indigenous peoples who, despite mounting pressures to move westward, continued to make their homes in the eastern states. Native Wisconsin villages often counted among their residents people from several different tribes, and intermarriage with itinerant and transplanted French traders since the mid-seventeenth century had also contributed to the multicultural presence throughout the Great Lakes region. Despite these changing geographic and sociopolitical circumstances, a number of tribes nevertheless maintained cultural and ethnic sovereignty. Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, however, many native residents faced displacement to territories west of the Mississippi, and in a succession of treaties to make way for white emigrants like the Carmans, the large Ojibwe population was forced to concede nearly two-thirds of northern Wisconsin by 1842, leaving them with a much reduced land base. The diminishment of sovereign territory was a pattern experienced, likewise, by many other tribal peoples and native villagers in Wisconsin during these decades.

It is unknown whether Lewis’s death in 1855 was caused by illness or perhaps the toll of the thousand-mile odyssey across the national map, but the schoolgirl sampler survived remarkably intact. With forethought to the object’s preservation and recognition of its historical significance, Lewis’s great-granddaughter Alice Palmer Washington entrusted the family heirloom to the Wisconsin Historical Society in 1984, yet another resting place on the map’s own passage through time and space from the moment when a young lady put needle to silk along the Hudson River.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to express thanks and appreciation to the staff at the American Antiquarian Society and the Wisconsin Historical Society for their assistance in making this article possible, and to column editors Ellery Foutch and Sarah Carter for their inspiration and thoughtful editorial guidance. Much gratitude also goes to David Rumsey for the generous provision of images from his esteemed historical map collection.

Further Reading:

The Cecilia Lewis map has been displayed for public view at the Wisconsin Historical Society, and in a 2007 Chicago exhibit sponsored by the Daughters of the American Revolution. It has also appeared in Betty Ring’s comprehensive text, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Needlework, 1650-1850, vol. II (New York, 1993). Ring’s books are an excellent resource for further reading on Quaker and other historic needlework in the United States. The accompanying image gallery features additional examples of schoolgirl embroidered maps, as well as other nineteenth-century objects used in teaching geography. As the century progressed, American-made map puzzles, geographic board games, and portable globes responded to new pedagogical philosophies and needs, and geography lessons continued to serve as vehicles for teaching patriotism, United States history, and concepts about space and place from an American perspective.

To read more about eighteenth- and nineteenth-century schoolgirl embroidery in the United States, see Gloria Seaman Allen, Columbia’s Daughters: Girlhood Embroidery from the District of Columbia (Baltimore, 2012), A Maryland Sampling: Girlhood Embroidery, 1738-1860 (Baltimore, 2007), and Mary Jaene Edmonds, Samplers and Samplermakers: An American Schoolgirl Art, 1700-1850 (New York and Los Angeles, 1991). Geographer Judith Tyner has written a number of articles on embroidered maps and globes: “Geography Through the Needle’s Eye,” The Map Collector 66 (Spring 1994): 3-7; “The World in Silk: Embroidered Globes of Westtown School,” The Map Collector 74 (Spring 1996): 11-14; and “Following the Thread: The Origins and Diffusion of Embroidered Maps,” Mercator’s World 6:2 (March/April 2001): 36-41.

For a thorough, insightful analysis of geographic education in the early republic, see Martin Brückner, The Geographic Revolution in Early America: Maps, Literacy, and National Identity (2006). Susan Schulten examined Emma Willard’s influential role in nineteenth-century geographic education in “Emma Willard and the graphic foundations of American history,” Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007): 542-564. For a history of nineteenth-century female education, see Margaret A. Nash,Women’s Education in the United States (New York, 2005). Historian Richard White unraveled the complex threads of Indian and European occupation and interaction in the upper Midwest in his groundbreaking text, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge and New York, 1991). To learn more about Wisconsin, see Robert C. Nesbit, Wisconsin: A History (Madison, Wis., 1989).

To read more about themes of progress and westward emigration in American landscape art, see Patricia Hills, “Picturing Progress in the Era of Manifest Destiny,” in William H. Truettner, ed., The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920 (Washington and London, 1991) and Roger Cushing Aikin, “Paintings of Manifest Destiny: Mapping the Nation,” American Art 14 (Autumn, 2000): 78-89.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.3 (Spring, 2014).

Mary Peterson Zundo received an MFA in printmaking and an MA in American art history from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where she is completing a dissertation on the interrelationships of maps and pictures in the construction of nationhood, race, and identity in the American West before and after the Civil War.