When the leadership of the woman suffrage movement lifted its self-imposed moratorium on political action following the Civil War, it released an enormous pent-up reserve of resolve, organizational momentum, and guarded optimism. Petitioning Congress for the right of suffrage, resuming annual woman’s rights conventions, initiating the first woman suffrage debate in the Senate, promoting universal suffrage, and lobbying national opinion leaders put the nation on notice that suffragists were determined to expand woman’s sphere. But prior experience with antebellum caricature alerted suffrage leaders to expect a vigorous visual barrage from illustrated periodicals in response to their political action. This essay examines the role of the art of condescension as an obstacle to the accomplishment of the suffragists’ hopes and dreams.

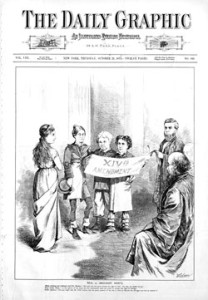

Only isolated, relatively good-natured missiles were fired in the first two years following the Civil War. Yankee Notions ridiculed “Miss Anthropy,” “Miss Timorous,” “Miss Susan Banter,” “Bridget O’ Toole,” and “Miss Susan Dash” in a series of cartoons aimed at universal suffrage. Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun, on its May 1867 front cover, chose the stereotyped fickle woman to rationalize opposition to suffrage (fig. 1). “When the ladies have votes,” contended the caption, “the best looking man will be their choice.” If “Good Looks Are Indispensable,” this would indeed be a “Blow for Congress.”

The year 1868 eclipsed the cumulative total of suffrage-related content for the two prior years. In part, this was due to the founding of the Revolution, a publication edited by Mrs. Stanton and Miss Anthony. In February 1868 an illustration by Frank Beard, published in the Comic Monthly, threw down its own gauntlet, depicting the eccentric George Francis Train, the financial backer of the enterprise, sharpening his own “Axe to Grind” on the symbolic whetstone of the Revolution (fig. 2). According to the cartoon, the women “turn the crank,” unknowingly promoting the sale of Train’s “Lots in Omaha.” Independent of the illustrator’s allegation of commercial exploitation, Train’s affiliation with the Revolution eventually proved to be a financial and public relations liability.

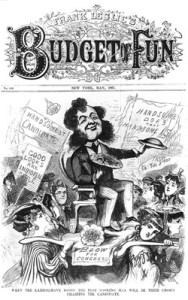

Cartoonists manipulated the meaning of the revolution metaphor for their own mischievous designs. In the periodical Days’ Doings, December 24, 1870, a clever illustrator sketched a comic “railroad accident”—an infant having soiled its diaper in a passenger car (fig. 3). The humor is contrived by the incongruous violation of a contemporary domestic custom: “A Meek and Well-Disciplined Husband ‘Fixes’ the Baby While His Wife [an enormous woman] Reads The Revolution.” Meanwhile, looking over the shoulder of the obedient husband, who is in the act of changing the baby’s diaper, an indignant male’s countenance visibly expresses dismay with the reversal of roles, while a woman across the aisle conceals her amusement with a strategically placed handkerchief over her face.

Yet the news of the formation of Sorosis, a New York woman’s club, generated a higher volume of popular art than the Revolution. On May 19, 1868, the front cover of the Illustrated News mocked the social innovation with a judgmental twist: “The Sour Sisters’ Club First Regular Meeting at Del Monico’s New York.” In June Harper’s Bazar countered this pejorative tone with an unqualified affirmation—”The Ladies Club at Del Monico’s—Women’s Rights and No Surrender.” The following month Phunny Phellow caricatured the New York woman’s club as “The Queen of Clubs” (fig. 4). Is it too speculative to assume that the incomplete lettering Miss S. on the scroll identifies Miss Susan B. Anthony as the queen?

Save a few exceptions, 1869 marked a discernibly negative philosophical change in the Harper’s Bazar editorial tone. To become a “girl of the period” or “wife of the period” was now tantamount to abandoning cherished traditional values. In January, Harper’s Bazar observed the “Girl of the Period” affiliating with the “Atalanta Skating Club,” “The Syren Flirting Club,” “The Pallas Billiard Club,” and the “Hippodamia Driving Club.” Moreover, the club fad was blamed for the “[b]aby left squalling” at home. “What’s to become of Baby?” asked Harper’s Bazar. Similarly the Harper Brothers’ flagship, Harper’s Weekly, devoted a double-page print to the alleged collective ills of Sorosis, and it caricatured a black woman in male attire at a woman’s rights convention as “The Colored Sorosis.” In the same vein, the “Modern Cornelia—a veritable Rum ‘un” in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was afflicted with “Female Suffrage,” “Sorosis,” “Universal Suffrage,” “Negro Suffrage,” “Gin,” “Rum,” “Brandy,” and the “Ballot Box.”

The celebrated political cartoonist Thomas Nast did more to alter the 1869 posture of Harper’s Bazar than any other artist. Suspicious that votes for female suffrage and equal rights threatened family values, he championed the “Lost Art” of domesticity and warned against the practice of “Cooperative Housekeeping.” In the December 1869 Phunny Phellow, Nast, who had made a living demeaning the Irish, denigrated women at Irish expense by combining ethnicity and gender identity to put an Irish woman in double jeopardy (fig. 5). The only way women could purify the ballot box, he reasoned, was for a stereotyped Irish cleaning lady to cleanse the outer sphere of the ballot box with “soap” and “soda” rather than purify the inner vessel with a wise, honest vote.

From 1867 to 1870, the progressive increase in cartoons in the illustrated periodical was linear. It peaked in 1870, but the volume of prints for the years 1869, 1871, 1872, and 1874 was respectable. What causal factors, other than those already mentioned, account for the frequency and negativity of content? In terms of the single most visible personality with respect to the sheer number of prints, Victoria Woodhull claims that distinction, even over Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. However, no event may have been more organizationally disruptive than when Horace Greeley and other prominent leaders abandoned women’s suffrage to fight for black suffrage.

This decision gave at least a portion of the women’s movement less access to Greeley’s New York Tribune. It also accelerated the pace for the adoption of the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution, dissolved the American Equal Rights Association, and substantially contributed to the division of suffragists into two separate and philosophically distinct camps—the National (NWSA) and American (AWSA) Woman Suffrage Associations.When the fifteenth amendment, which guaranteed black Americans the right to vote, was ratified in 1870 Punchinello ‘s Henry L. Stephens celebrated with a full-page illustration of “The Great National Game”—American baseball (fig. 6). “Our Colored Brother,” proudly wearing the belt of the forty-first Congress as part of his sparkling new national uniform, swings the bat—labeled fifteenth amendment—with consummate confidence at the approaching ball, enthusiastically exclaiming to a woman (in the on-deck circle)—carrying the bat of the sixteenth amendment—and her electively disfranchised Chinese and Alaskan companions (who, incidentally, carry no symbolic bats), “Hi Yah! Stan’ Back Dar; it’s Dis Chile’s Innin’s Now!” So it was; the fifteenth amendment, now ratified, inclined suffragists toward the sixteenth amendment.

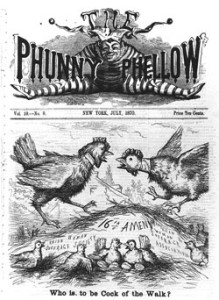

But the ineluctable fracture between the competitive National and American Woman Suffrage organizations caused Phunny Phellow to ponder which association would seize the mantle of leadership in the fight for the sixteenth amendment. Would it be Theodore Tilton’s National Woman Suffrage Association or Henry Ward Beecher’s American Woman Suffrage Association? Paradoxically, a full front cover spread in Phunny Phellow‘s July 1870 issue framed the question in masculine terms: “Who is to be the Cock of the Walk?” (fig. 7). The cartoonist maneuvered Tilton and Beecher, the two roosters, into battle posture for a good old-fashioned cockfight to determine who would lead the quest for “suffrage” and “women’s rights.” Truthfully, the AWSA’s commitment to patience and moderation yielded the center stage to the NWSA.

In the meantime, two new charismatic players, the sisters Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin, had become part of the drama, thanks to Commodore Vanderbilt’s world of stock brokerage on Wall Street. The whirl of publicity surrounding the female stock brokers was dizzying but quite favorable. On February 26, 1870, Days’ Doings pictured “the lovely financiers” at “work in their private office.” One week later Harper’s Weekly displayed the women as “the Bewitching Brokers.” In April, Yankee Notions simply drew them as the “female financiers,” while Punchinello comically ascribed their success with Mr. Vanderbilt to the ladies’ entrancing “Mesmerism in Wall Street.”

However, the stunning breakthrough in national prestige for Victoria Woodhull came on January 11, 1871, when she appeared on behalf of the NWSA before the House Judiciary Committee. On February 4, 1871, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper gracefully pictured her as a dignified woman and commended her performance for taking “far higher ground than has usually been assumed by her coadjutors. Her sex’s right of suffrage she claims under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, showing that women possess the right to vote now, without a Sixteenth Amendment.” This brilliant act suddenly transferred the suffrage ordeal from the legislative to the judicial arena.

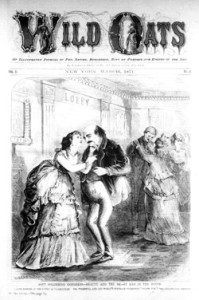

In March, Wild Oats featured Victoria Woodhull on its front cover, lobbying Ben Butler in “Beauty and the Be_st Man in the House” (fig. 8). An April cartoon in Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun showed an enamored Ben Butler following Victoria Woodhull “on the trail for woman votes.” On May 6, 1871, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper humorously represented Uncle Sam trying to persuade President Grant to put “the Best General,” an attractive woman suffragist (Victoria Woodhull or Tennessee Claflin?), on “that Southern Commission of yours… and you’ll hear but little more of the Ku-Klux.” In fairness, these were not derogatory images.

But the glow of the “Woodhull Memorial,” as Victoria Woodhull’s congressional petition was called, was like a fire-fly at night, flashing its brilliance for a moment only to flicker and die out. Of course, the memorial would not finally succumb until it had its day in court—the Supreme Court—but an impatient press could not wait.

Still, the print mystique of Victoria Woodhull and her sister began to tarnish in June 1871. Days’ Doings, for example, meticulously chronicled the sisters’ embarrassing family domestic problems. The superficial tarnish became more corrosive as the St. Louis German-language Puck and Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun reported Victoria’s advocacy of free love. Whisperings of spiritualism, socialism, and radical ideas in the Woodhull and Claflin Weekly further tainted Victoria’s reputation. By January 1872 the front cover of Wild Oats depicted Woodhull, “the Fair Angler,” dangling various lines of temptation—”Husband Every Day,” “Free Love,” “Immorality,” and “No Marriages”—to gullible males (fig. 9). The sign below her shuttered windows reads, “Vic Woodhull—Teacher of and Broker in Free Love—Immorality?—General Adventuress—Office Wall St.—Sign of the Golden Satyr.”

Another Wild Oatscartoon proclaimed Horace Greeley and Victoria Woodhull (who was nominated for the presidency by the Equal Rights Party) as separate entries in the 1872 presidential race. Greeley was riding “the well known nag Protection,” and Woodhull was astride “Free Love—No Marriage.” In June, Nick Nax, Wild Oats, and Days’ Doings each published cartoons depicting the Equal Rights Party’s nomination of Victoria Woodhull for president and Frederick Douglas for vice president. Days’ Doings called it “The Free-Lovers Convention in Apollo Hall, New York.” One illustration in Wild Oats described the convention as “The Woman’s, Negroes, and Workingman’s Ticket.” The other noted that the convention “Resolved that the Lordly Arrogance of Man in Determining the Sphere of Woman is Adverse to the Spirit of the Age.”

The sisters suffered the additional indignity of being incarcerated in the Ludlow Street Jail just days before the presidential election. They were charged with “circulating obscene literature through the mails.” That literature consisted of the sensational announcement in the Woodhull and Claflin Weekly that Reverend Henry Ward Beecher was alleged to have had an illicit relationship with the spouse of Theodore Tilton. The indictment of so prominent a reformer as Beecher further fueled the attacks on the suffrage movement. Now an early stalwart of women’s suffrage was said to be immoral—not least in a newspaper devoted to the cause of equal rights. The impact of what one paper referred to as “The Monster Scandal” can be seen in “The Brooklyn Plymouth Minstrel Troupe,” which appeared in Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun, November 1874 (fig. 10). The cartoon denounced Beecher, Tilton, Woodhull, Stanton, Anthony, and Ben Butler—all principals in the movement to expand women’s sphere. In May 1875 Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun demeaned Anthony and Tilton—”Miss Susan B. Anthony sits on the knee of the Monster Tilton. ‘She jumps up mighty quick,’ when detected by Miss Bessie Turner.” The relentless attack continued in the next issue, with a print that showed Beecher, Anthony, Stanton, Woodhull, and Claflin all sitting on Tilton’s elongated knee in a compromising position (fig. 11). The caption explained the scene as “What it will come to if Tilton goes on using that knee in this loose manner.”

Still the Woodhull Memorial had laid the groundwork for a judicial review of whether or not the recently amended constitution now guaranteed women the vote. Reaction to this development may partly explain the treatment of suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony who was arrested for civil disobedience after voting in the presidential election.

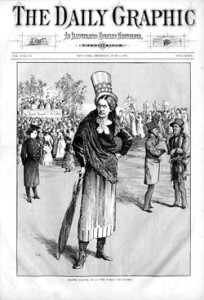

On May 8, 1873, the New York Daily Graphic pictured “Miss Anthony Telling the Story of Her Arrest to the Woman Suffrage Convention.” The next month, on June 5, 1873, the Daily Graphic accorded Miss Anthony front-cover publicity as “The Woman Who Dared” (fig. 12). “[She has] been held to account before the law for this daring deed,” revealed the text, “but [her] trial seems more than likely to [de]generate into a farce, if indeed it is ever held.

However, should the lady succeed, the result will be such as our artist has predicted in the surroundings of our graphic, Statue No. 17.” What the artist had predicted was a fundamental reversal of roles: “the female policeman will be a terror to male nurses and marketers. Oratorical women will hold the public rostrum and then a torch-light procession of dazzling beauties will prove a wonderful sensation in coming elections.” Nevertheless, the editorial conceded, “Whenever women rule the hour, they must acknowledge the person of Miss Anthony, the pioneer who first pursued the way they sought.” The trial was held and Anthony was found guilty (though not required to pay the fine).

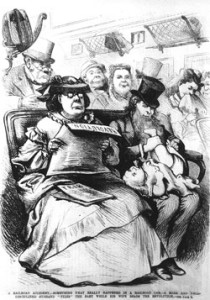

Thanks to the case Minor vs. Happersett the substance of the Woodhull Memorial did receive the Supreme Court’s scrutiny. The disappointing verdict was announced on October 21, 1875, in a front-page visual editorial in the New York Daily Graphic (fig. 14). The cartoon pictured Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anna Dickinson with Chief Justice Waite and bore the title, “Real Versus Imaginary Wants.” The subtext made the paper’s view clear.

Misses Anthony and Dickinson and Mrs. Stanton: We hold that this [the fourteenth Amendment] gives women the right to vote any way you might let us.

Chief Justice Waite: In the opinion of the Court, the 14th Amendment does not confer on women the right of suffrage.

Public Opinion: And you might add, Mr. Chief Justice, that the great question of the day is how to improve the suffrage, not how to extend it.

On January 31, 1874, the New York Daily Graphic conceived a cartoon showing a woman-suffragist athlete attempting to match the long jump record of a black male athlete, who, in the symbolic leap toward the fifteenth Amendment, acquired the vote for black, male Americans (fig. 14). “I ought to be able to jump as far as Cuffee,” shouted the high-flying, ambitious woman. But postbellum caricature and a host of other complex factors, internal and external, deterred partisans of woman suffrage from achieving their laudable goals until a more level playing field was installed in the twentieth century.

Further Reading:

For related articles see the author’s “Antebellum Caricature and Woman’s Sphere,” Journal of Women’s History 3:3 (Winter 1992) and his collaborative work with Carol B. Bunker, “Woman Suffrage, Popular Art, and Utah,” in Carol C. Madsen, ed., Battle for the Ballot, Essays on Woman Suffrage in Utah” (Logan, Utah, 1997). Other essays by Bunker on nineteenth-century pictorial themes include: “The Campaign Dial: A Premier Lincoln Campaign Paper,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 25:1 (2004): 186-202 and with John Appel, “‘Shoddy,’ Anti-Semitism, and the Civil War,” American Jewish History 82:1-4 (1994): 43-71.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Gary L. Bunker is emeritus professor of psychology at Brigham Young University; his most recent publication relating to the history of prints is entitled, From Rail-Splitter to Icon: Lincoln’s Image in Illustrated Periodicals, 1860-1865 (2001).

![Fig. 5. "Women will Purify the Ballot Box—Shakspere [ sic ]." Front cover of Phunny Phellow 10:1 (December 1869). Courtesy of the Collection of Richard West/Periodyssey.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/7.3.Bunker.5-222x300.jpg)