On November 15, 1850, at the American Hall in Hartford, Connecticut, Otis Bullard debuted his “Panorama of New York City,” a 3,000-foot-long painting depicting the streets, residents, and sights of lower Manhattan. The exhibition’s six-foot-high canvas was rolled, in several sections, onto cylinders, and then slowly unfurled before an audience who had paid twenty-five cents each for a two-hour presentation. Like other moving panoramas, Bullard’s transformed its subject into a pictorial narrative: from the corner of West Street and Cortlandt Street, the panorama’s virtual stroll took viewers down to the Battery, then east to Broadway, and then back uptown along the city’s most famous thoroughfare to Union Square, where the exhibition concluded. Starting his panoramic tour at the island’s westernmost edge, where disembarking ferry and steamboat passengers encountered the waterfront hotels of West Street, Bullard placed his viewer in the position of a visitor arriving from the mainland United States.

This was no accident, for the panorama’s virtual tourism was carefully marketed to viewers in small cities and towns far enough away from New York that they would be willing to pay to “see the elephant” in painted form at their local concert hall or church. Over the course of the work’s seventeen-year career, during which time it was seen by hundreds of thousands of Americans, Bullard’s panorama was never exhibited anywhere in or near New York City itself. While residents of cities such as St. Louis delighted in seeing their streets and buildings represented in the many Mississippi River panoramas of the late 1840s—stories circulated of people gleefully recognizing their homes up on the canvas—the “Panorama of New York City” was made for a distinctly nonurban audience.

Bullard’s panorama, originally a visual medium, exists today only as the elusive object of written texts: promotional materials, newspaper testimonials, a descriptive pamphlet, and a few other scattered documents (fig. 1). Though the panorama’s original paintings have been lost to history, these surviving artifacts have much to teach us about the marketing and presentation of Bullard’s work, and about the meaning of New York City in the mid-nineteenth-century national imagination.

Perhaps the most surprising lesson of his story is that, though the moving panorama is often seen as a modern form of visual storytelling, one that invites analogies with the twentieth-century motion picture, in the hands of Bullard it was a technology of nostalgia. Front and center in the exhibition of the “Panorama of New York City” was the artist himself, whose careful, and carefully staged, labor invoked a model of artisanship that looked back to a pre-urban past. The workmanlike brushstrokes, like the orderly progress of the moving image itself, promised viewers a stable perspective from which to witness the spectacle of the modern city. By presenting the morally suspect metropolis neatly framed by the panorama’s rhetoric of integrity and respectability, Bullard offered audiences an inoculation against urbanization and the social and economic chaos it threatened to bring with it.

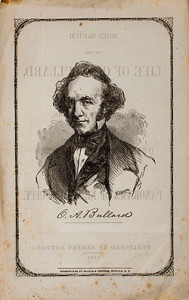

The story of Otis Allen Bullard and his moving panorama is very much a story of nineteenth-century America. Born in 1816 in Steuben County, New York, Bullard apprenticed during his teen years as a sign painter in the shop of Augustus Olmstead, a local wagon builder. In 1838 he moved to Hartford, Connecticut, where he retrained in the art of portraiture under local artist Philip Hewins. Over the next few years, Bullard enjoyed a successful career in New England and upstate New York, painting portraits of many prominent families, including the Dickinsons of Amherst (he painted a ten-year-old Emily along with her two siblings in 1840 [fig. 2]). By the early 1840s, the popularity of daguerreotypy had begun to undermine his business. Bullard would need more than portraits to survive.

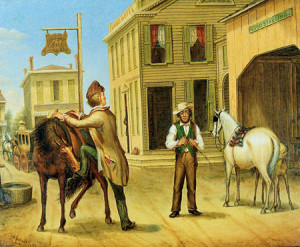

Relocating to New York City in 1843, Bullard encountered a different kind of marketplace than he had ever known before. Though he continued to work in traditional forms—he found some business in New York as a portraitist, and embarked on a series of historical and genre paintings depicting scenes from small-town American life (fig. 3)—the city afforded the struggling artist both the subject matter and the capital necessary to change the scale of his ambitions. Perhaps inspired by the Mississippi River panoramist John Banvard, he began pursuing the idea of painting a huge moving picture of New York City in 1846. Armed with capital from George Doel, an English-born financier, and business savvy from Albert Norton, a managing agent, Bullard began to create the panorama, an undertaking that took four years and ultimately cost $15,500. Like countless other men of his generation, Bullard began his working life as an artisan and ended it as a businessman.

Drawing on his own experiences as a rural-born artist confronting the metropolis, Bullard portrayed New York from the perspective of a well-informed visitor who was nevertheless an outsider. He presented a city in which the republican ideals of respectable labor and trade were giving way to a social landscape in which everyday actions such as walking down Broadway, or riding a stagecoach, were class-inflected performances. By exhibiting the social divisions of antebellum New York within the solid frame of Bullard’s production, the panorama invited audiences to imagine themselves outside the new urban vocabulary of bourgeois wealth and lower-class poverty. The moving panorama thus offered a dynamic bridge between the preindustrial and industrial eras: at once an artistic and economic undertaking, the “Panorama of New York City” blended craft and spectacle in rendering the modern city—and the new social order it represented—a commodity that could be marketed to the masses.

By 1850, New York City had emerged as a prominent symbol of industrialization’s chaos. In the work of Lydia Maria Child, George G. Foster, George Lippard, Edgar Allan Poe, and other first-generation urban writers, the city appeared as a bewildering realm of class conflict, violence, immorality, psychological alienation, financial instability, and social flux. Against such a backdrop, Bullard’s panorama offered provincial audiences a way of both seeing and not seeing the new metropolis: It presented a carefully expurgated picture of New York, one that, through careful strategies of selection, omission, perspective, and narrative presentation, effaced many of the city’s most troubling realities as it neatly mapped out the upheavals of northern antebellum life.

At the same time, the panorama offered audiences a way of seeing themselves. Unlike works of urban journalism or popular fiction, or even other visual media such as traditional painting and engravings, the moving panorama presented the individual spectator with the opportunity to look at a canvas as part of an audience that was both physically present and imaginatively projected into the future and the past. After all, the “moving” form that the panorama so often took in the United States meant that it was both moveable in its style of exhibition and portable in its ability to travel across the Northeast and Midwest, to places such as Rochester, Worcester, and Cleveland. At each stop, the panoramic audience saw the painted metropolis from the stability and familiarity of their own local environment.

If New York was a spectacle by which the stability of nonurban life was defined, the moving panorama offered a singular medium for drawing such a contrast. Whether their subject was California, the Mississippi River, or New York, panoramas promised unimpeachable realism: buildings were shown in proper scale and colors, just as the figures that appeared were said to be portraits of actual people. But just as significant was the narrative logic, the story-telling, afforded by the movement of the canvas. The descriptive pamphlets that survive from the popular Mississippi River panoramas of the 1840s suggest how the moving canvas sought to defuse the controversies symbolized by pictures of steamboat fires, Native American removal, and slave plantations; however troubling the implications of these pictures, they were quietly resolved as the canvas rolled across the stage, telling a broad tale of the national past, present, and future (fig. 4). Rendering violence as spectacle, the moving panorama kept pace with the process of modernization by enfolding instances of disorder or conflict into a panoramic tale of the developing and expanding nation.

Images of flatboatmen, highlighting the difficult manual labor of their work and the face-to-face nature of their trading practices, shared the canvas with pictures of failed and utterly desolate towns planned by financial speculators; such juxtapositions offered cautionary tales of ungrounded and irresponsible economic ambition during an age of frequent financial panic. In addition, Mississippi River panoramas often included cross-sectional images of a typical steamboat, revealing the different classes of accommodations available to travelers. Given the narrative progression followed by the Mississippi River panoramas—from the relatively undomesticated lands of the upper river to the bustling commerce of the region from St. Louis down to New Orleans—the spectacular appearance of a burning steamboat late in the exhibition suggested the potentially dangerous implications of unchecked industrial development. In these and many other ways, the moving panoramas of the 1840s and 1850s offered American viewers a mass cultural form large enough to frame the economic anxieties, social tensions, and political conflicts of the age; if the panoramic eye could take in the disparate elements of national life in one exhibition, the nation itself could cohere as a symbol capable of containing such multitudes.

In the case of Bullard’s work, the panorama taught audiences how to make sense of a new kind of social landscape. Before presenting the street-level “perspective” scenes that made up the bulk of his painting, the “Panorama of New York City” began with a “Bird’s-Eye View” in which, Bullard explained in his narration to the audience, “we suppose ourselves to be elevated considerably above New York City; looking down upon it” (fig. 1, see “Bird’s Eye View”). Looking south from Union Square, and with New Jersey visible in the not-too-distant background, he helps viewers locate the city’s major arteries, which organize the more detailed scenes that are to follow: “The finest hotels and stores in New York are situated in Broadway,” while “Fifth Avenue isone of the finest streets of private residence in the city.” Bullard also sets up New York as a place where class stratification can be mapped by neighborhood: The “most wealthy and fashionable families in New York … generally reside north of Washington Square and on the west side of Broadway. The poorest class of inhabitants reside east of the Bowery.” There is no chaos here, the viewer is assured before being brought down to street level, only a new kind of landscape.

This new landscape required a new way of seeing, and Bullard stood prepared to instruct his audience in it. Until his death in 1853, he often delivered the narration that accompanied the panorama himself. Whether Bullard was present at the exhibitions or not, the descriptive narration called attention to the decisions about selection and presentation that allowed the artist to properly stage the city for the viewer. “We now pass through the centre of the Battery,” the audience was told at one point. “By that means we have a finer view of the bay and shipping.” At moments such as this, Bullard invited his audience down to street level, only to reorient their vision from that of the urban dweller to the broad, all-encompassing perspective for which the panorama was named. By moving back and forth between the street-level and the wide-angle, the panorama allowed viewers to organize every detail of urban life within the “bird’s eye view” that opened the exhibition. In this way, Bullard’s depiction of New York kept the city simultaneously in view and at arm’s length.

Claiming that “New York city is more like a foreign city than any other city in the Union,” Bullard’s narration treated the cityscape as both an actual place that could be captured in pictures and as a symbolic realm just beyond the borders of mainstream Americanness. Furthermore, seeing New York as a “foreign” spectacle invited Bullard’s viewers to imagine themselves as a homogenous class securely located apart from the upper and lower extremes of New York society. On the lower end of Bullard’s New York are recently arrived immigrants from Europe. “All grades of life, and people from all countries,” the narration informs us, “can be seen in front of St. Paul’s church every day; it is a favorite place of resort for them.” Accentuating the unassimilated status of one particular group, the narrator tells us that “Three Hungarians are seen in their native costume.” Similarly, nonwhite figures most often appeared on Bullard’s canvas in positions of servitude or buffoonery. A figure is described by the narration as “one of the colored artists of the city, probably going to paint a Panorama somewhere with his white wash brush.” Of another figure, the narration informs us that “[w]e can see all of this servant except his face—that is rather too black!” And a military company is shown heading out for target practice, with “the colored man carrying the target.”

Like so many other representations of the antebellum city, the canvas highlighted the “great contrasts in life every fine afternoon, from the utmost extravagance and wealth to the most abject poverty and misery.” Amid the spectacular parade of poverty and wealth, the pamphlet describes the “accidents and confusion” to be found on Broadway “almost every hour of the day.” Here Bullard depicted an accident “in which the poor milkman got the worst of it,” spilling his milk and water, and in which “[t]he butcher had a pretty hard time,” getting knocked out of his cart and onto the street. Another scene suggests that the city’s rampant profit-seeking was giving rise to a modern pandemonium:

The proprietor of this charcoal wagon, had painted upon the side, “all orders thankfully received and punctually attended to.” He is now about receiving an unexpected order in the rear. The gentleman in this carriage employed a new coachman on trial, and this was his first attempt at driving the horse—his first appearance in public. He didn’t know how to guide the horse, and run him into the charcoal wagon, and followed on after himself. It was said at the time, that he went in this end of the wagon an Irishman, and come out the other end a negro.

This scene presents the city’s common laborers as the victims of a ruthless urban marketplace. As the description of the milkman puts it, these workers are often getting “the worst of it”—though they, too, have been corrupted by urban profiteering (for, as the audience is told elsewhere, the water spilled by the milkman is used to dilute his wares). The audience is invited to laugh at every member of the urban tableau: the nouveau riche “gentleman” who employs an untrained coachman; the overly solicitous charcoal salesman; and the unassimilated foreigner, standing in for a degraded and vulnerable laboring class whose racial integrity is threatened by the servitude required of them. In an urban social landscape in which identity is merely a matter of changeable surfaces, one false move and an Irishman can become “a negro.”

Instead of depicting the merchants, doctors, lawyers, teachers, clerks, and other members of New York’s new middle class (which by 1855 included about thirty percent of the city’s workforce), Bullard filled in the space between the upper and lower classes with undignified laborers. The above passage from the panoramic lecture directs the city’s exploitation and degradation toward the lower and laboring classes; here and elsewhere, the exhibition evaded the complex class politics of antebellum New York, where an urban working class was emerging alongside the burgeoning (and, on Bullard’s canvas, absent) middle class. Instead, the “Panorama of New York City” offered its audiences a way of looking at urban social conflict that allowed them to keep their hands clean as they gazed up at the morally suspect city.

Indeed, a poem inspired by Bullard’s work, written by Ephraim Stowe of Massachusetts, highlights the artist’s careful selection of urban details as a (market-savvy) rehearsal of middle-class moralism: “Had the painter disclosed all of the secrets within, / And brought out the wretchedness, suffering and sin, / That, hidden beneath this magnificence lies, / With sickness at heart you’d turn off your eyes.” Offering viewers a way of both seeing and not seeing New York, Stowe’s Bullard stages for the panoramic audience the selective logic of respectable spectatorship: “But the beautiful painting presents to the view / The City, bedecked in a most charming hue; / Her beauty and grandeur the pencil reveals— / Her poverty, sorrow, and crime, it conceals.” These elements are not simply absent from Bullard’s picture; rather, their absence is itself a visible feature of the panoramic presentation. In describing his picture of the notorious Five Points Neighborhood, for example, Bullard informs his audience: “The characters to be seen around this building at all hours of the day and night are not represented upon the painting. I did not wish to disgrace it with their presence.”

Newspaper accounts similarly treated Bullard’s work as a moral performance on the part of both artist and audience. The Kalamazoo Gazette reported that “every phase of city life and incident, proper to be represented, is introduced.” The notice continues by linking the artist’s own good taste with the presumed ability of the paying crowd to recognize how to read the work’s moral undertones: “No one can view this panorama without admiring the artistic skill, the eminent good taste, in the introduction of incidents, and the patient labor of the artist who brought it out.” And in a move that is typical of these journalistic notices, the Cayuga (Ohio) Chief focuses carefully on the orderly and well-behaved crowd that sits in a local church, watching and approving of the passing images. “During the whole exhibition such is the interest felt by all that you can almost hear a pin drop,” reports the paper. “[S]uch was the case here to crowded houses, in the Baptist Church, and we presume it is so everywhere.” As these newspaper puffs quietly assure their audiences that Bullard’s work constitutes a respectable entertainment, the city functions as a cultural symbol allowing nonurban audiences to imagine themselves collectively beyond the reach of urban corruption.

The panorama’s focus on the surfaces and exteriors of New York City contrasted with both the urban sensationalism of George Foster’s “New York by Gaslight” and the bourgeois progressivism of Lydia Maria Child’s Letters From New York. While each of these writers sought out the city’s interiors, the panorama keeps the viewer’s eyes expressly on its exteriors. Bullard never takes us indoors and he is content to render all inhabitants as representative objects. In a striking contrast to Child’s treatment of urban poverty, in which the figure of the city urchin offers an opportunity for spiritual and moral sermonizing, an anonymous poem entitled “Going to the City” celebrates Bullard’s work for its presentation of “Beggars, whose petitions / Ne’er excite our pity.” And a scene from the panoramic pamphlet describes a peddler on Broadway near Vesey Street as a mere placeholder for the urban poor: “This apple-woman has been stationed at this lamp post for four or five years, selling apples and candy to passers-by. If she should leave for a day, some one else would take possession of her place, and she would probably lose the means of supporting herself and family.” Another passage describing “one of the poor beggar children” depicted on canvas quickly zooms out to capture a whole class of people: “There are over six hundred poor children in the streets of New York begging and stealing. Their parents are generally intemperate, dissipated vagabonds.” In opposition to Child’s quest for intimacy and sympathy, Bullard’s narration moves from the singular to the plural, casting human figures as representative types.

Bullard also invited viewers to gaze upwards at the spectacle of urban wealth. Compare Bullard’s depiction of the affluent with that appearing in a series of articles entitled “New-York Daguerreotyped,” which ran in Putnam’s Monthly beginning in February of 1853. These pieces included engravings of well-known New York buildings as well as extended descriptions and commentary, offering a touchstone for considering Bullard’s own pictures of mid-century New York. In both word and image, Putnam’s portrayed the burgeoning metropolis as evidence of the nation’s capacity to create a moneyed and enlightened social elite to rival that of Europe. The city as a symbol of endless renewal and redevelopment is made in these pages to serve a bourgeois imagination whose taste and refinement contrasts sharply with the lower and middling classes.

At one point, the Putnam’s writer describes the changing character of Broadway, which formerly had been “consecrated to the dwellings of the wealthy” but is increasingly a commercial realm: “Aristocracy, startled and disgusted with the near approach of plebeian trade which threatened to lay its insolent hands upon her mantle, and to come tramping into her silken parlors with its heavy boots and rough attire, fled by dignified degrees up Broadway… Alas for the poor lady, every day drives her higher and higher.” Amid this distasteful mingling of the upper and “plebeian” merchant classes, the magazine educates its bourgeois audience about how to read the city’s architecture: “Too many buildings in New-York show immense wealth to have been expended in their construction, with a lavish hand unguided by correct taste.” Elaborate cornices and wood pediments “painted and sanded in imitation of stone” are part of an urban landscape that requires and invites the ongoing performance of bourgeois refinement. At the same time, Putnam’s witnesses the city’s dining and lodging establishments from the perspective of one who might partake in its luxuries. Of the newest generation of hotel dining-rooms, we are told that “The aesthetics of the table are now more cultivated by our hotel-keepers than was the case a few years ago. The dining-room of the St. Nicholas is an exquisitely beautiful example of a banqueting room, and shows to what a high condition the fine art of dining well has already been carried in this city.”

Bullard, however, places his audience on the street, looking in at urban opulence: “This is the principal entrance to the Astor House—people are seen inside… It is said that there are about twelve hundred rooms … and three stories below.” Here and elsewhere, Bullard includes extensive details about the cost and materials of particular structures and locales, especially when these figures approach the other-worldly. Similarly, the stagecoaches available for hire on Broadway epitomize the city’s conspicuous display of wealth and status: “A fine stage will get more custom in Broadway than an old one. Persons had rather pay their six pence to ride in a fine stage.” One stage, which “took the premium one year, at the Fair of the American Institute,” reportedly cost $1,100. “It was painted very beautifully on the outside, and fitted up with mirrors inside.” The viewer also learns that “Drivers take pride in having six or more horses on a fine stage when it is first brought out in the street,” and that one particular stage included “twenty-two spans of white horses, all driven by one man.”

While the ornamental ideals of the city’s stagecoach owners serve and reflect a culture of ostentatious display, Bullard’s realist ethos implicitly claims for his work a more stable and honest kind of value:

The people we see in the street are drawn from life. There are several thousand portraits upon this painting that would be readily recognized by their friends in the city, by their style of dress and general appearance in the street—have been drawn from the persons themselves at different times they were seen in the street, expressly for this painting.

The painting’s realism defines the city residents entirely by “their style of dress and general appearance in the street” so that the artist can claim to have captured the essence of the city precisely because his eye understands how urban identity privileges the symbolic language of fashion. As the audience looks out at a New York where the “upper ten” announce themselves by how they dress, and by the coaches they employ to carry them up and down Broadway, the panoramic audience pays twenty-five cents to enjoy the respectable entertainment that is the product of Bullard’s labor.

A widely circulated biographical sketch presented Bullard as “one of the noble few, in our country, who have by their own exertions been elevated from adversity to a high and honorable renown.” And a broadside advertising the panorama included a newspaper clipping, under the heading “Young Men, read this!” suggesting that the facts of Bullard’s life “will interest all who have struggled and are struggling with poverty” (fig. 1). The panorama included an exterior view of the Broadway building in which he and his small team of assistants worked, and when Bullard died in 1853, many commentators speculated that his untimely death was due to the astonishing, even superhuman amount of labor required to carry out such an enormous project. Like the wood and canvas of the panorama itself, Bullard’s labor was the solid machinery that framed for audiences the less tangible forces transforming New York as a commercial and financial realm. When read in conversation with the artist’s pictures of the city, the example of Bullard’s life story offered a model of respectable poverty that was in marked contrast with the undignified and nameless urchins displayed on his canvas, and one that viewed noble labor as a route into middle-class stability.

Of course, this careful presentation of Bullard’s labor was itself a product of the very economic forces the panorama claimed to be keeping safely at a distance. The panorama’s managers peddled Bullard’s integrity to markets that imagined themselves as witnesses to the process of urbanization. Even from the planning stages, the “Panorama of New York City” was apparently conceived as a less urban counterpart to another New York City exhibition, John Evers’s “Grand Original, Moving Series of Panoramas.” The Evers panorama depicted Manhattan, the (then separate) city of Brooklyn, the East and Hudson Rivers, and the Atlantic Ocean, and was underwritten by the sarsaparilla millionaire Samuel P. Townsend. Clearly intended for a more urban, working-class audience, Evers’s work—which first appeared in 1849, and which is only known to have exhibited in Manhattan and Washington, D.C.—was advertised to include “The awful and magnificent scene of the ASTOR OPERA HOUSE RIOT” and “The grand and sublime spectacle of the BURNING OF THE PARK THEATRE.” No event in the recent memory of the city invoked the violence of urban class conflict as dramatically as the Astor Place riots, and the panorama’s advertising only reinforced its embrace of working-class sensationalism. In addition, an item in the December 8, 1849, issue of the New York Herald reveals that another artist, presumably Bullard, was at work at an imitation of “Evers’ grand moving panorama of New York.” While a short notice the previous month had recommended the Evers work to its readers, the Herald describes this new work as both unprofessional and distinctly nonurban. It is, the paper argues, “as complete a piece of scene-daubing as was ever got up by a wandering Thespian company in a country barn.”

Bullard and his confederates likely decided that the “Panorama of New York City” would find its audience far outside the city’s borders. While the Evers advertisements promise a near-apocalyptic presentation of the city in flames, Bullard offered the city in frames, assuring audiences that despite the tensions and confusions of urban life, New York was eminently capable of monitoring and protecting both people and property. Thus one view portrays a “vehicle used to convey prisoners in, and about the city,” while another shows the notorious city prison, “The Tombs.” In still another scene we see a policeman walking a prisoner into the station of the city’s sixth police ward. Bullard’s narration continues: “A prisoner escaping: an occurrence that happened while I was making a drawing of the building. Two policemen are seen in pursuit; they soon overtook him.” Here and elsewhere, potential threats to urban order and hierarchy are contained without even a hint of drama or suspense. Though the class conflicts of the Evers panorama are matters of life and death, in the “Panorama of New York City” such conflicts ultimately reaffirm the city’s social order, and are at times (as in the Broadway accidents described above) even lightly comical.

Also noteworthy in this regard is Bullard’s portrayal of city fires. Conflagration scenes were among the most popular highlights of many mid-century moving panoramas, in part because the form’s dependence on lighting effects made for some rather spectacular staging possibilities. Instead of introducing a fire unannounced into the narrative, however, Bullard first describes for his audiences how the city is laid out into eight fire districts: “When a fire occurs in any part of the city, the men at the bells readily know the district in which it is situated, and they make the number of the district known to the firemen, by the number of strokes upon the bells.” Once a fire finally appears several scenes later, Bullard almost off-handedly points out the burning of a relatively undeveloped piece of land: “This fire represents the burning of a mahogany yard, situated near the North river. It gave an opportunity of showing the manner in which the firemen turned out to a fire.” Here again the artist turns an opportunity for sensationalism into an act of rhetorical distancing: “We here see some of the bustle and confusion attendant upon a fire, but we don’t hear any of the noise. This is not represented on the Painting.“

The narrative location of crime, fires, and other urban perils in Bullard’s work ultimately affirmed the city’s capacity to maintain standards of security and control. Though the “Panorama of New York City” acknowledged the real danger of fires in a region populated as densely as antebellum New York, those most vulnerable were either the firemen themselves (who came almost exclusively from the city’s lower classes) or sensation-seekers (who by virtue of their appetites fall short of middle-class morality): “Boys often run with the engines to the fire. They frequently fall down and are run over. There is hardly a fire in New York but what there is some kind of accident, persons being injured in running to the fire, or firemen at the fire.” Whether depicting a fleeing criminal caught without drama, or a burning lumber yard in which no bodies are at any physical risk, the panorama answered the city’s sensationalism, theatricality, and disorder with his panorama’s counter-urban rhetoric of respectability and self-government.

The “Panorama of New York City” implied that true middle-class refinement was possible only outside the borders of the city and the forms of class consciousness offered by urban life. Nowhere is this clearer than in the exhibition’s final scene, which depicted a space associated by 1850 with a bourgeois ideal of comfort and security: the residences surrounding Union Square Park. As the descriptive pamphlet reads, “There is a policeman, or keeper of the park, here stationed to keep out improper characters and dogs, to preserve order and keep persons off the grass; and it is a safe place for parents to send their children for play and exercise.” Removed from the spectacular parade of wealth and poverty seen farther down Broadway, the scene offers a closing image of upper-class security that defines such a status by the protection the city itself offers from the “improper” and potentially dangerous classes that move freely farther downtown.

When the city’s more respectable workers are finally mentioned in Bullard’s final scene, they are not only disconnected from the work that they perform during the week; they appear, paradoxically, as an absence. As the description continues, during the week “we see this park thronged with little children,” while on Sundays it “will be thronged with the working classes.” Such phrasing suggests that the view on canvas is not a Sunday view—that is, these workers do not actually appear before the audience. Perhaps even more tellingly, the narrative “we” that looks up at the painted scene resides somewhere between the uptown families seen throughout the week, and those who work such long hours that Sundays are “nearly their only days for recreation and pleasure.” Bullard’s exclusion of these mechanics sets up an implicit contrast between the urban laborer and the panoramic audience, who enjoys the leisure of the exhibition as the mechanics are off at work.

With the city’s police keeping a careful eye out for “improper characters,” Union Square offers mechanics only a weekly parody of respectability in which their families are entitled to briefly loiter in the reflected light of bourgeois exclusivity. Having taught his audience how to view the city from within the bounds of propriety, Bullard closes by highlighting the unbridgeable, almost ontological gulf between working class and bourgeois identity in the modern city. By framing such a dilemma as a distinctly urban phenomenon, the panorama offered a collective identity—homogeneous, white, nonurban—unfractured by a city-based class system in which labor and capital are kept conspicuously apart.

In the months before his death, Bullard completed a painting that vividly illustrates his panorama’s idiosyncratic way of witnessing and containing the spectacle of urban life. “Horse Trade Scene, Cornish Maine” (fig. 5) centers on a rural horse trader who has presumably just completed a transaction with a departing gentleman. In the background, through the open side door of a tavern, the viewer can just make out a broadside advertising “Bullard’s panorama of New York City,” to appear “this day” at a local hall. The painting depicts the kind of face-to-face economic transaction that would increasingly distinguish small-town American life from the complex financial transactions and speculations of urban capitalism. Of course, as the inclusion of the panorama broadside suggests, this small-town integrity was essentially counter-urban, depending as it did upon the distant-but-visible city for its own articulation. Bullard’s panorama promised its audiences precisely what it brings to “Horse Trade Scene”: a portable city framed, as it is in Bullard’s late painting, by the rhetoric of honest exchange and unpretentious realism.

“Horse Trade Scene” also reflects the careful marketing of Bullard and his work as a link between small-town commerce and an urban economic landscape that loomed in the distance. In 1854, the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser recognized the fundamentally commercial nature of Bullard’s exhibition:

We wish to tell the merchants and shopkeepers of New York that the panorama advertises widely and generally—more so than it can be done by any other single medium. In the western towns their shops and stands are seen by those persons to whom it is important to them that the information should be communicated, and the exact location of the different places of business becomes fixed in the minds of the spectators… . In Bullard’s panorama every sign and name is seen as distinctly as on Broadway, and over eighty thousand are represented faithfully on canvas. Thus the western dry goods merchant beholds the sign and name of some wholesale firm with whose reputation he has become acquainted probably through the medium of the papers, and when he visits New York for the first time, he bends his steps at once to the familiar spot.

Clearly aligned here with the mercantile interests of the industrializing North, the panorama was nonetheless appearing before audiences who (in some cases) imagined themselves as only distantly connected to the commercial activity on display before them. As an 1854 review from the Ohio Cultivator promised, “Our country friends may pay their twenty-five cents to see this safely.” And in fact, even the business-minded piece from the Buffalo paper remarks that “no little fun can be obtained from watching the upturned countenances, open mouths and staring eyes of the ‘country volks’ who have never seen the Broadway elephant.” As the writer concludes, Bullard’s scenes of New York “are almost incomprehensible to novices accustomed only to country life or the miniature turmoil of a smaller city.” Pointing at Broadway with one hand and at the wide-eyed country yokels with the other, the Buffalo writer articulates a middle ground from which the city is demystified as an economic entity; seen panoramically, New York merely comprises thousands of individual “merchants and shopkeepers” who have been made “familiar” by Bullard’s painting.

By peddling both New York City and the artisanal accomplishments of Bullard, the managers promoted New York’s mercantile activities while keeping the panorama’s own connections to the city’s marketplace out of view. Selling the panorama as the well-crafted product of honest labor, Bullard’s team made it more palatable to audiences who might be distrustful of an urban commercial venture. Of course, the very fact that this market strategy emerged out of New York City’s increasingly speculative economy only reaffirms the far-reaching implications of those forces Bullard claimed to be containing within the frames of his picture: the “Panorama of New York City,” after all, was an economic venture born in the very city it claimed to be keeping safely at a distance.

Though the unprecedented economic growth of New York throughout the 1850s meant that Bullard’s painting became more obviously out-of-date every year, it continued to find success in the marketplace as a piece of cultural nostalgia. In “Going to the City,” the panorama is a delightfully premodern technology (“Though the Locomotive / Run a trifle faster”), and Bullard’s painted city a quaintly fictional projection of the nonurban imagination (“Happy is the urchin / Humming rural ditty”) (fig. 1). As the refrain, “With a nimble ‘quarter’ / Going to the City,” repeats in each of the poem’s ten stanzas, the “Panorama of New York City” embodies a welcome predictability that opposes the seeming chaos of present-day urban life. For the price of a “nimble quarter,” the viewer gets to experience a simpler, less modern New York, one that contrasts favorably with the New York of the late 1850s. As the reader is reminded, “Hoops were never worn in / Eighteen Hundred fifty.”

Bullard’s unique and colorful story highlights the difficulty of generalizing about the moving panorama as a cultural phenomenon. Though, for example, the medium is typically associated with the formation of an American middle class in cities such as New York, Bullard’s work rejected the very premise of an urban middle class—not only by eliding this class in his pictures of 1850 New York, but by offering a middle-class respectability that was defined against the stratified logic of urban social life. And while it is often tempting to imagine these early “motion pictures” as a proto-cinematic medium aligned with the forces of modernization, we have seen how the “Panorama of New York City” offered a way of witnessing the city that was firmly grounded in the ideals of the early nineteenth century. Finally, the story of Bullard’s work complicates the broad claim that moving panoramas brought distant regions closer to an emerging mass audience. In fact Bullard’s panorama appears to have succeeded in the marketplace by keeping the burgeoning metropolis, and the new world it represented, safely at a distance.

Further reading

A copy of the descriptive booklet from Bullard’s panorama can be found in the Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago. The American Antiquarian Society holds one of the few extant copies of the “Brief Sketch of the Life of O.A. Bullard,” which includes a number of press clippings praising the exhibition. In addition, broadsides advertising the panorama can be found at the AAS and the New York Historical Society. An invaluable resource on Bullard’s panorama (including a careful reconstruction of the exhibition schedule) is Joseph Arrington’s “Otis A. Bullard’s Moving Panorama of New York City” in New York Historical Society Quarterly, 44:3 (1960): 309-35.

The most informative book-length studies of the panorama phenomenon in Europe and the United States are Stephan Oettermann’s The Panorama, trans. Deborah Lucas Schneider (New York, 1997) and Bernard Comment’s The Painted Panorama (New York, 1999), though neither of these studies specifically mentions Bullard’s work. John Francis McDermott’s The Lost Panoramas of the Mississippi (Chicago, 1958) provides a valuable overview of five different Mississippi River panoramas. These panoramas are also the subject of a chapter in Thomas Ruys Smith’s River of Dreams: Imagining the Mississippi River Before Mark Twain (Baton Rouge, 2007).

For an excellent discussion of mid-nineteenth-century literary and journalistic treatments of New York City, see Stuart Blumin’s introduction to George G. Foster’s New York by Gas-Light and Other Urban Sketches (Berkeley, 1990). To better understand the class dynamics of antebellum New York, see Bruce Laurie’s Artisans Into Workers: Labor in Nineteenth-Century America (New York, 1989); Sean Wilentz’s Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1790-1850 (New York, 1984); Stuart Blumin’s The Emergence of the Middle Class: Social Experience in the American City, 1760-1900 (Cambridge, 1989); Sven Beckert’s The Monied Metropolis: New York and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850-1896 (New York, 2001); and David Scobey’s “Anatomy of the Promenade: The Politics of Bourgeois Sociability in Nineteenth-Century New York,” Social History, 17:2 (May 1992): 203-227. Finally, anyone curious about pre-1900 New York can learn something from Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York, 2000), by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace.

Thanks very much to the following institutions: the Winterthur Library, especially the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera; the Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York; the American Antiquarian Society; the Joseph Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago; the New York Public Library; the New York Historical Society; the Brooklyn Public Library; and Swirbul Library at Adelphi University. Special thanks to Joe and Jay Caldwell at the Caldwell Gallery in Manlius, New York, for bringing their Bullard painting to my attention. I am also very grateful to the editorial staff at Common-place, especially Cathy Kelly and Trudy Powers.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.4 (July, 2011).

Peter West, assistant professor of English at Adelphi University, is the author of The Arbiters of Reality: Hawthorne, Melville, and the Rise of Mass Information Culture (2008). He is currently working with a team of co-editors on a five-volume collection of documents related to the panorama in England and the United States, to be published by Pickering and Chatto.