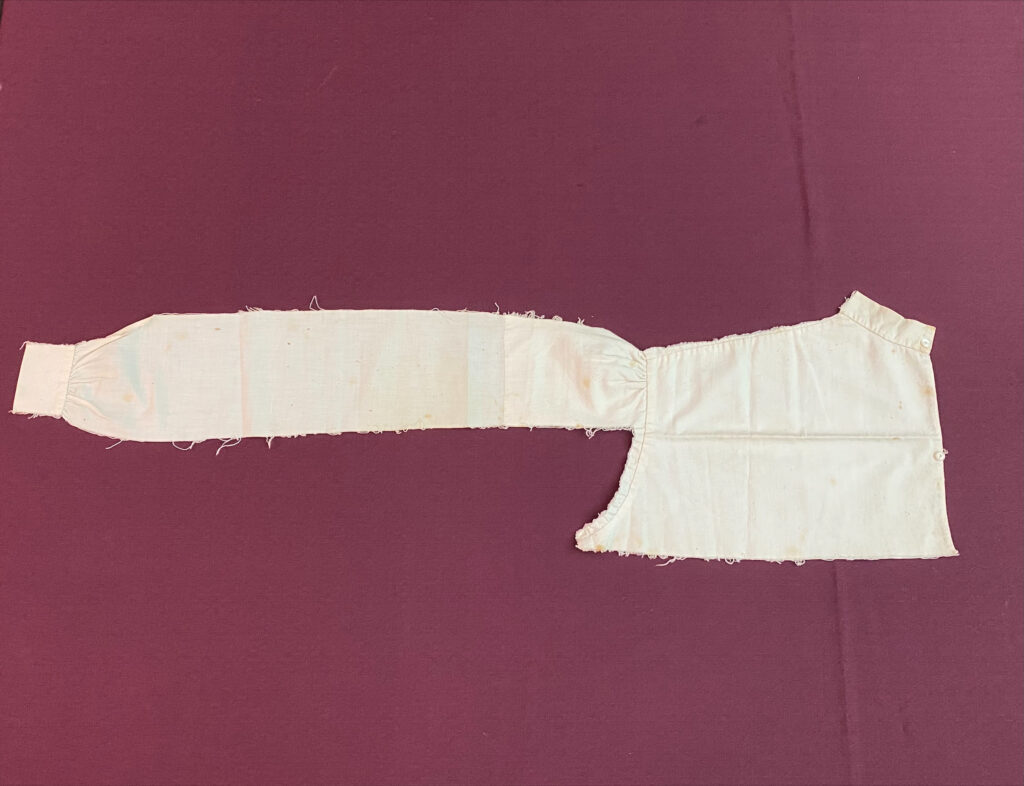

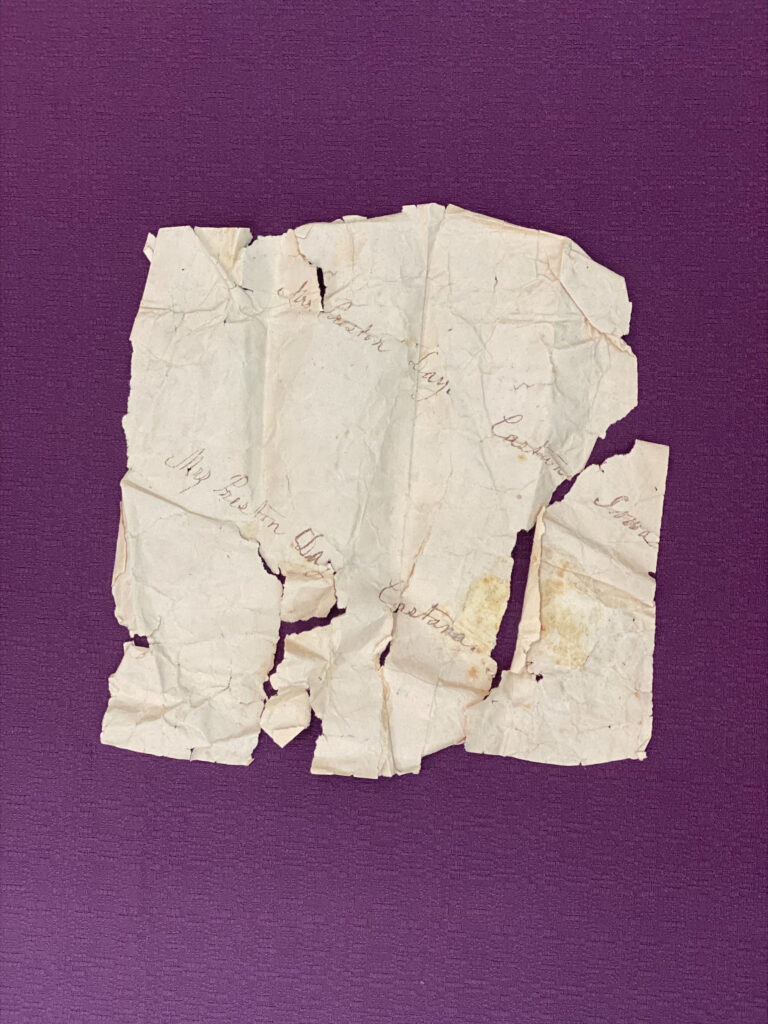

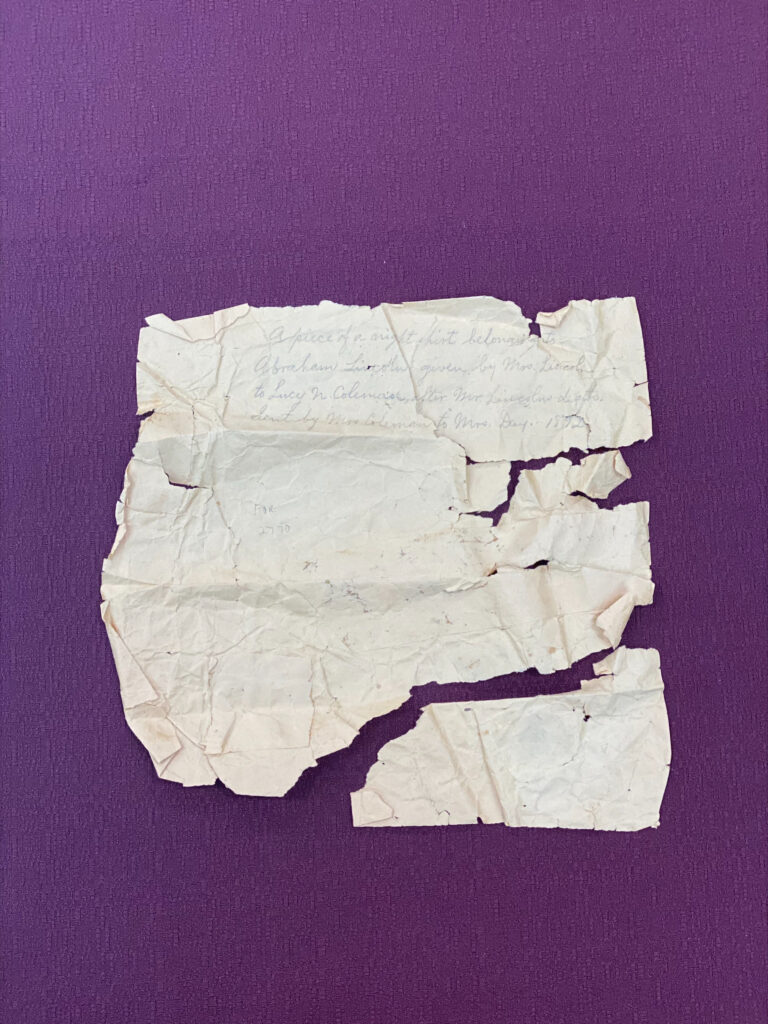

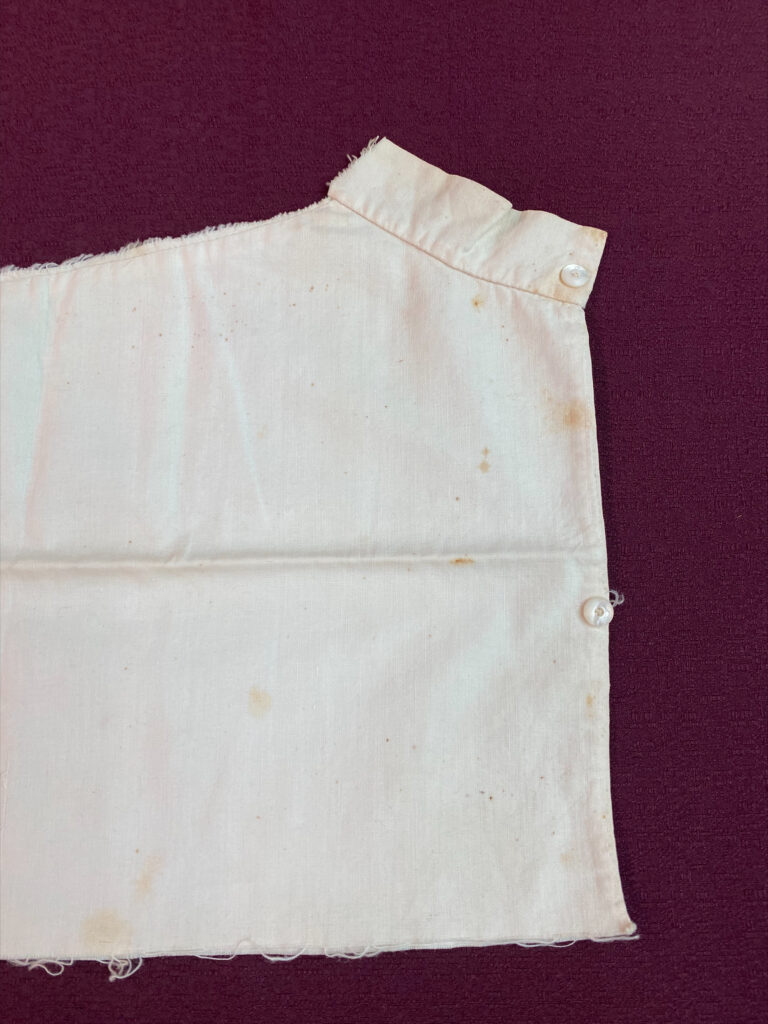

Experiencing authentic historical objects in a museum or archive can have a range of effects on us, especially when that object belonged to a prominent person. Objects bind us to our history; they can provoke emotional energy and foster complicated attachments. In the Williams Gallery at Mississippi State University, the sleeve of a night shirt that is believed to have belonged to Abraham Lincoln is on display. The artifact is part of the expansive Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana. According to our main textual evidence of the object’s provenance, Mary Todd Lincoln gave the night shirt to abolitionist and feminist Lucy Newhall Colman after the president’s assassination. In 1892, Colman sent a sleeve of the night shirt to family friend, Caroline “Carrie” Day. However, the shirt’s path from the Day family to the Williams Collection is uncertain, due mostly to the challenge of storing and cataloguing such a vast collection prior to its relocation to a university archive. Nonetheless, the strong possibility that this shirt sleeve once rested on the arm of the beloved president gives the object a powerful emotional appeal.

The Fabric of Our Nation: A Nineteenth-Century Night Shirt Reveals the Complex Value of Material Objects

Commemoration, commerce, and complex social connections combined to dictate the paths and diversions of this obscure object and others.

The night shirt was carefully cut into sections, presumably by Colman. For those who might have revered the piece of clothing as a sacred relic, this common act allowed for multiple people to experience the object as a site of history and memory. The shirt’s fragmentation and distribution also worked to multiply the object’s possible monetary value. Although it can be assumed that Lucy Colman simply gave Carrie Day the sleeve due to their personal connection, she may have sold the remaining pieces. Indeed, Lincoln’s murder, and his subsequent transition in national memory to becoming a “Martyred President,” transformed any objects associated with the president into powerful and valuable relics. Commemoration, commerce, and complex social connections combined to dictate the paths and diversions of this obscure object and others. But with the provenance uncertain for this particular object, how is it still valuable to us today?

The night shirt’s first career as a utilitarian object emphasizes just how ordinary it was across both class and race. By the mid-nineteenth century, northern textile mills were spinning cotton into cloth and streamlining clothing production with the help of sewing machines, participating in the growing industry of mass-production and what historian Michael Zakim terms “ready-made democracy.” This “ready-made commodity” embodied the social mobilization possible because of the Industrial Revolution. The standardization of the making and selling of (mostly men’s) clothing provided a wide variety of consumers with money-saving convenience.

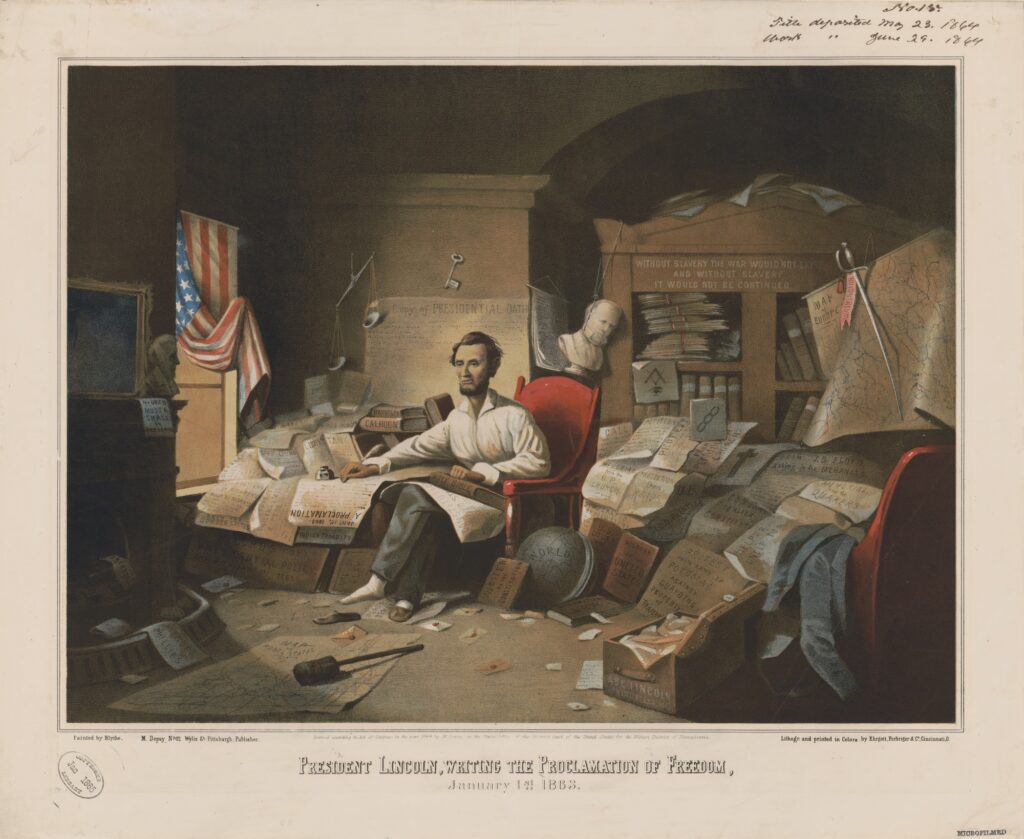

To further unravel the shirt’s history, we must acknowledge that this cotton night shirt exposes the relationship between the period’s mass-producing textile industry and the slave society of the American South. To be sure, the delicate materiality of the night shirt, itself seemingly representative of a democratic republican culture of civility and gentility, is at odds with the human cost of cotton’s production. The social relationship between the labor of cotton production and the commodified cotton shirt, between the laborer and consumer, mirrors a complicated contest between opposing ideas of civilization in nineteenth-century America.

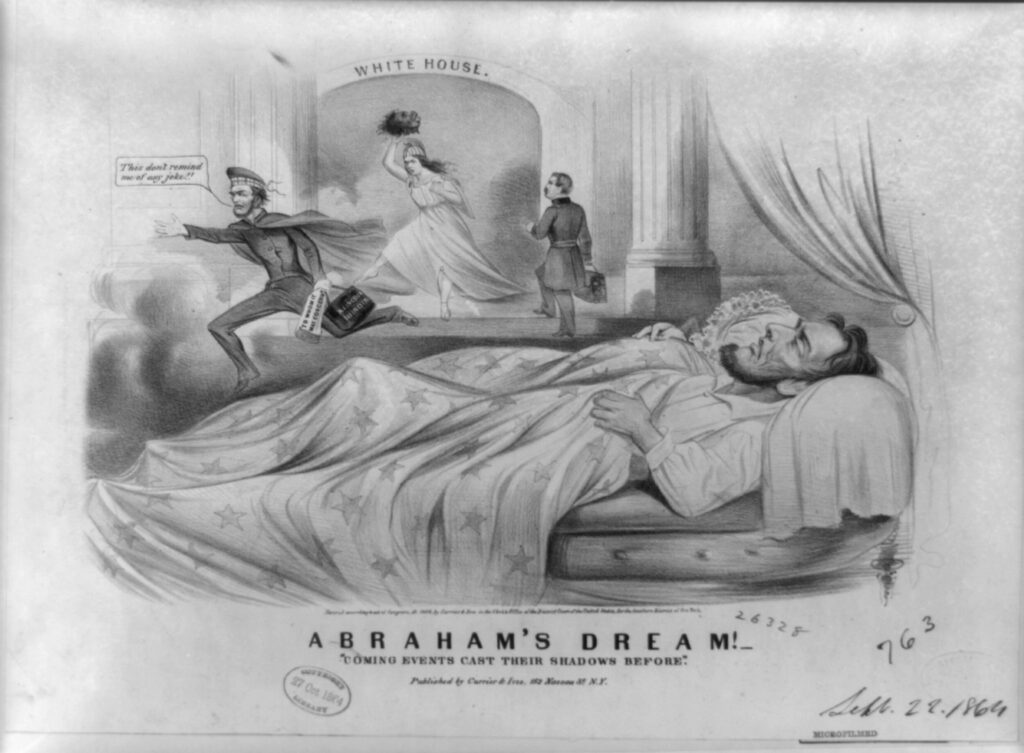

If the night shirt did in fact previously belong to the president, its purpose, meaning, and value were dramatically transformed after Lincoln took his last breath. The nation, already in mourning following a bloody Civil War, now had to also reconcile with the sudden death of the president. In Mourning Lincoln (2016), historian Martha Hodes writes that “by gathering and preserving relics, the bereaved sought confirmation of the cataclysmic event [of his death], wrote themselves into the history they had witnessed, and enshrined the past for the future.” Lincoln-related relics became representations of national loss, tangible evidence of the national trauma that Americans struggled to come to terms with. Trophies, souvenirs, keepsakes, sacred relics—objects became a bonding agent between a troubling past and an uncertain future.

In Behind the Scenes or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868), Elizabeth Keckley, a seamstress for Mary Lincoln, claims that Mary gave her several keepsakes following the president’s death. She recollects two objects in particular—a comb and brush: “With this same comb and brush I had often combed his head. When almost ready to go down to a reception, he would turn to me with a quizzical look: ‘Well, Madam Elizabeth, will you brush my bristles down to-night?’ ‘Yes, Mr. Lincoln.’ Then he would take his seat in an easy-chair, and sit quietly while I arranged his hair.” Keckley was “only too glad to accept this comb and brush” from the hands of the president’s widow. Her memory of this intimate interaction exemplifies why personal, everyday objects are so valuable for historians and anthropologists. Objects such as these offer an intimate sensory experience, allowing us to feel what the person felt. A shirt and a comb provide us with a sense of the man that we cannot access by reading written documents. As historian Teresa Barnett points out, nothing permits us to engage with the past quite like the “substance of the past itself, materially identical to what it was in that other time and yet equally here and participating in our present.”

Sacred relics provided a material means of engaging with loved ones and memorializing events. For Mary Lincoln, the shirt might have functioned as a material continuation of Mr. Lincoln’s existence after his death. However, according to Keckley, Mary Lincoln gave away all objects that were “intimately connected with the president,” as she “could not bear to be reminded of the past.” After the shirt was transferred, the object-subject relationship and experience changed, as well as the object’s value.

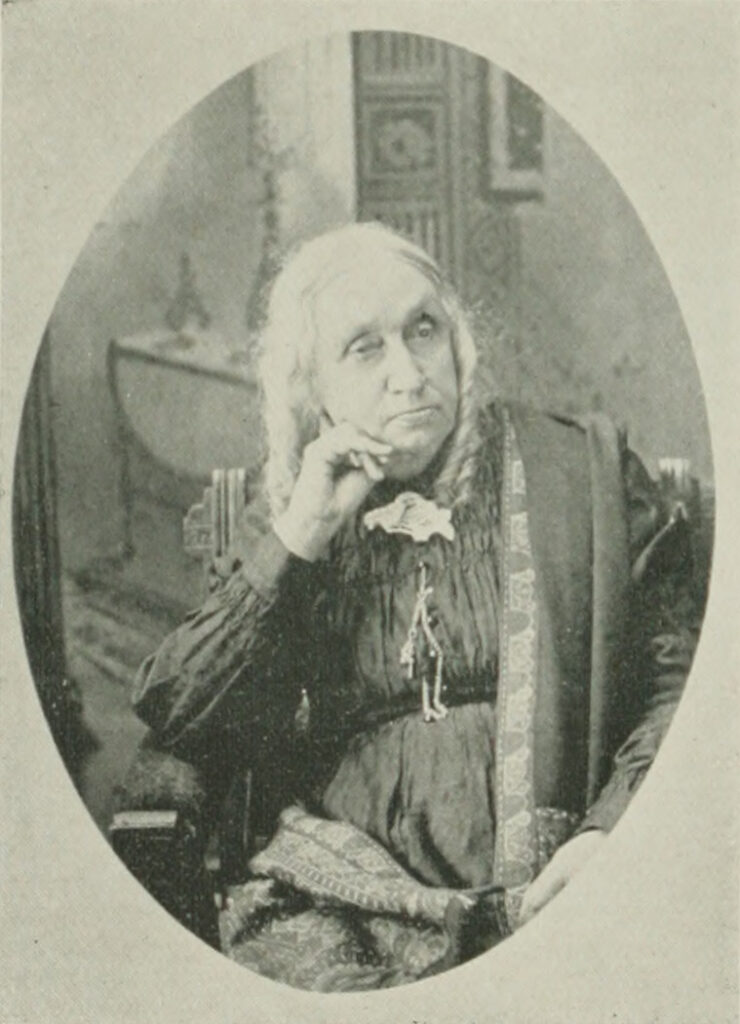

If the documentation is accurate, Mary passed the night shirt to Lucy Colman, the abolitionist who had escorted Sojourner Truth to the White House in 1864. After the war, Colman possessed several relics that we might find reasonably strange today: tufts of grass from the yard of Jefferson Davis’s Richmond home, a whipping post and slave whip, and a piece of Lincoln’s coffin. Yet, she had given all of these objects away by the time she wrote her 1891 memoir Reminiscences. The only relic still in her possession at the time was the night shirt. In the memoir, she describes the night shirt (and Mary Lincoln) as “strange.” Her ambivalence toward the object echoed her skeptical attitude toward the president. Colman did not shy away from critiquing the controversial president in her publication. Her ambiguous feelings about Lincoln and his legacy might explain her decision to cut and distribute the night shirt. Also, this ambiguity is illustrative of a fragmented and fraught relationship between Americans and the “Great Emancipator.”

Regardless of how she viewed Lincoln’s ethics, Colman must have sensed the intensifying historical value of the night shirt. By carefully and deliberately cutting and distributing objects, Americans shared and created new memories of the national trauma. Moreover, the act also provided individuals with an opportunity for recognition and trade. Circumstantial evidence reveals that it was through her sister, Aurelia (Danforth) Raymond, that Colman likely met Carrie Day. Raymond and Day both studied medicine and both were living and practicing at the same time in Onondaga County, New York. Carrie Day’s family eventually settled in Castana, Iowa, and her own feelings about the president may be understood through her decision to name one of her daughters Cornelia Lincoln Day. What happened to the shirt sleeve following Caroline’s death in 1904 remains unclear. The complicated journey and negotiations of Civil War era relics, like this very night shirt, illuminate the complex evolution of memorializing the Civil War. The transfer of objects, and the resulting social networks, continuously reanimated and reinvented meaning and value. Why would Caroline’s children sell or give away an object that clearly had deep meaning for her? Could ambivalent feelings about Lincoln have contributed to this decision? One obvious possibility is that the economic value of the shirt may have outweighed its sentimental value. Just as it is feasible that Lucy Colman sold the remaining pieces of the shirt, Caroline Day’s family may have also profited from selling the sleeve.

Abraham Lincoln’s violent death added a complex dimension to collecting presidential memorabilia. The national tragedy enhanced both the material and immaterial value of all Lincoln-related objects. In Stuart Schneider’s Collecting Lincoln (1997), he acknowledges that collectors began their work “even as Lincoln lay dying.” As collecting grew, the focus began to shift from an emphasis on commemoration to an investment opportunity. An obsession with the monetary value of Lincoln-objects by some collectors began to hinder an important relationship between collecting and scholarship. Therefore, not only has collecting and preserving been vital to the ever-growing scholarship on the Civil War era, but so has the willingness of collectors to open up their collections to scholars for study or even give their collections to educational institutions.

The Frank and Virginia Williams collection of Lincolniana was donated to Mississippi State University in 2017 and is housed alongside the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library. Both collections are prime sources for Civil War research and, surprisingly, are located in the state that was only second to secede from the Union. The Lincolniana collection consists of over 30,000 items, approximately 16,000 of which are pamphlets and books. In a recent interview, Williams explained that his decision to give this collection to the southern university was rooted in his own hope that the collection’s presence in this location would aid in the continued process of healing between the North and the South, suggesting that the fight for freedom did not end at Appomattox but “is an ongoing process even today.”

This night shirt, now displayed in a glass case, is valorized into a decommodified value system. Its fragmentation is evidence of the object’s complex value, while its careful preservation now as a museum object also indicates that it is historically invaluable. The night shirt began as an ordinary shirt—a common product for any common man. But after the president’s death, the object transformed into something much different and much more powerful. If truly believed by its various holders to be a sacred relic, an extension of Lincoln himself, then it may have provided a means for coping with the complex wounds of war.

Despite the object’s ambiguous provenance and journey, it continues to facilitate important social relationships; this is proven through the valuable interactions that were prompted by this very project. It continues to provoke important questions about what material objects can tell us about our nation’s history: what other stories can be embodied in historical objects? We are continuously compelled to weave together the complicated story of our nation. Written texts can only provide us with a limited understanding of our past. Maybe it is through the medium of material objects that we can work to secure the missing pieces.

This article originally appeared in December 2022.

Further Reading

Teresa Barnett, Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Lucy Colman, Reminiscences (Buffalo: H.L. Green, 1891).

Martha Hodes, Mourning Lincoln (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., 1868).

Stuart Schneider, Collecting Lincoln (Atglen: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1997).

Frank J. Williams and Mark E. Neely Jr., “The Crisis in Lincoln Collecting,” Books at Brown—Lincoln and Lincolniana (Providence: The Friends of the Library of Brown University, 1985).

Michael Zakim, “A Ready-Made Business: The Birth of the Clothing Industry in America,” Business History Review 73 (Spring 1999): 61-90.

Michael Zakim, Ready-Made Democracy: A History of Men’s Dress in the American Republic, 1760-1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Acknowledgments

Special thank you to Chief Justice Frank J. Williams and his wife Virginia, Mississippi State University archivist Dr. Ryan Semmes, and independent historian Jake Harding of Castana, Iowa.

Amber Morgan Gill is an English Literature and Composition lecturer at Mississippi State University, as well as a part-time History Ph.D. student there. She studies the Civil War era with special interest in republican motherhood, sentimental nationalism, and the value of material objects.