Currier and Ives’s Civil War

The April 2007 issue of Common-place was devoted to graphics in nineteenth-century America. It was titled, “Revolution in Print.” As the authors of that issue’s introduction wrote, “Technological innovations—from the invention of photography to the development of a variety of mechanized processes for reproducing images on a scale never before imagined—coupled with expanding transportation and communications networks, engendered a veritable avalanche of pictorial publications and products.” No one contributed more to that “revolution in print” than Nathaniel Currier and James Ives. In this article, I will focus on Currier and Ives’s Civil War. But first, let me provide a brief introduction to Currier and Ives and why an article on them is an appropriate addition to those essays published two years ago.

Printmakers to the American People

Those with only a passing knowledge of Currier and Ives usually identify them as the creators of “things Americana.” That was certainly true, but they did much more. Currier and Ives called themselves “Printmakers to the American People” and their company “the Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints.” They advertised their company as “the best, cheapest, and most popular firm in a democratic country,” and they lived up to that billing. Over the course of a half century, Currier and Ives produced more than seven thousand prints that sold in the millions of copies, at one point accounting for 95 percent of all lithographs in circulation in the United States.

When Nathaniel Currier started his business in the 1830s, lithography was still a relatively new technology—less than forty years old. The Bavarian, Alois Senefelder, invented lithography while searching for an inexpensive way of printing his plays in multiple copies. Literally translated as “writing on stone,” the process involved using a grease crayon to create an image on stone. Ink was then applied to the surface and a mirror image of the drawing produced by pressing paper to it. The chief advantages of lithography over engraving and etching were its lower-cost materials and much speedier production. Within a few years European printers began issuing lithographic prints by local artists, but that idea was slow to catch on in the United States.

In 1834, after serving six years as an apprentice with lithographers William and John Pendleton in Boston, Nathaniel Currier started his own company in New York City, which would become the center of lithography in nineteenth-century America. Like those from whom he learned the trade, Currier began work as a job printer. He used lithography to duplicate whatever a customer needed—labels, letterheads, handbills, and architectural plans—in as many copies as requested at only pennies a copy.

In 1840 Currier produced the first of his famous “disaster prints,” picturing the sinking of the steamboat Lexington in Long Island Sound, which took the lives of over one hundred people. When the print was reproduced in the New York Sun, Nathaniel Currier became known nationally, and disaster prints and others depicting the news events of the day became his staples. In the 1850s, James Merritt Ives, who married into the Currier extended family and whom Currier hired as a “bookkeeper,” came up with the idea of marketing prints that “presented the plain daily experiences and pleasures of American life”—those prints with which Currier and Ives are most closely associated today.

Currier and Ives never intended to produce prints of great value. They sold their products for as little as fifteen cents and no more than three dollars. Rather than aspiring to have their work exhibited in the nation’s fine-art museums and galleries, they sought to have it hung on the walls of America’s homes, stores, barbershops, firehouses, barrooms, and barns.

Currier and Ives’s Civil War

The pictorial record of the Civil War was far greater than that of any previous war. The new art of photography, however, even in the hands of Mathew Brady, was still comparatively rudimentary. The shutter’s slow speed, for example, limited the photographer’s subject matter to that which stood still. As a result, the artist’s sketchpad continued to dominate the market. As one critic put it, “for the picture industry, the war was a blessing,” and Currier and Ives made the most of it.

Currier and Ives produced more than two hundred prints of the American Civil War—the vast majority of which purported to illustrate the great battles of the war. Insofar as the proprietors had any direct experience with the war, it was quite limited. Ives served during the war as a captain in the New York State National Guard, but he saw action only briefly when Lee invaded Pennsylvania. Otherwise, he worked to promote Union enlistments in the New York City area. Neither Currier nor anyone else highly placed in the company—as far as I could find—participated in, or even witnessed, a battle. Further, their exact position on the war is difficult to gauge for lack of any significant personal correspondence or other documentation. What is clear is that the printers freely exploited the conflict for commercial gain. And that meant, above all, tracking the attitudes of Northern middle-class consumers. One finds little moral ambiguity in the prints from this period; on the whole, the Civil War prints of Currier and Ives plainly reflect the ideals of the North, the Republican Party, and its leader, Abraham Lincoln.

The War

In stark contrast to the reality that appeared through the lens of photographers like Mathew Brady and in the pages of illustrated weeklies like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, Currier and Ives produced a long list of patriotic prints that portrayed the sacrifices made by Union soldiers and their families—like The Union Volunteer (1861), The Flag of Our Union (1861), The Spirit of 61/God, Our Country and Liberty (1861), The Soldier’s Dream of Home (1862) and The Brave Wife (undated). To these they added a steady flow of romanticized battle scenes beginning with Bombardment of Fort Sumter (1861), which shows the Union installation under attack and the American flag flying high above the fray and smoke—reminiscent of the scene at Fort McHenry in 1814 recalled in “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Northern news weeklies’ loyalty to the Union complemented their hatred of the South. Continually assailing slaveholders and Confederate political and military leaders as treasonous in politics and barbarous in war, they freely blamed the seceding states for all the nation’s troubles. Lest their images disrupt the peaceable sanctuary of the middle-class parlor, Currier and Ives tended to emphasize Northern righteousness rather than Southern depravation.

In the first few months of the war, Currier and Ives produced The Hercules of the Union, Slaying the Great Dragon of Secession (1861). It shows Union General Winfield Scott wielding a club labeled “Liberty and Union” in the face of a Confederate serpent with seven heads—one for each of the seven original seceding Southern states. As the title suggests, Scott acts with some dispatch.

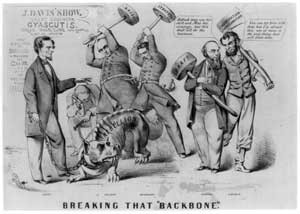

This is not to say that Currier and Ives prints were incapable of nuance or dissent. Breaking That Backbone (1862) (fig. 1), for example, pictured the various Union plans to subdue the South, none of which has succeeded in breaking the back of the “Great southern Gyascutis.” Generals Halleck and McClellan wield sledgehammers labeled “Skill” and “Strategy.” Secretary of War Stanton holds a hammer labeled “Draft,” while Lincoln holds an axe labeled “Emancipation Proclamation.” In the background sits a man, head in hand, despondently holding a small hammer labeled “Compromise.”

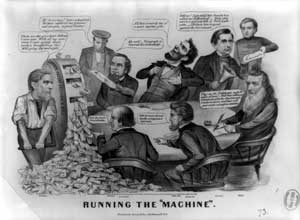

Two years later the even more critical Running the Machine (1864) (fig. 2) appeared, wherein various members of the Lincoln administration are attacked for corruption and failed policies. Secretary of the Treasury Fessenden is shown directing the manufacture of a flood of greenbacks, complaining of the greed of his fellow Union leaders, while contractors demand more funds. Seward is shown suspending habeas corpus and planning arbitrary arrests, and Lincoln—known, but not always appreciated, for his sense of humor—leans back and exclaims that all of this reminded him of a “capital joke.”

During the early months of the election year of 1864, compromise still was an issue. Things were not going well for the North, and the Democratic candidate George McClellan posed a serious challenge for the incumbent. Although Currier and Ives had been critical of McClellan early in the war for his failed military efforts, they nevertheless gave him equal time as an alternative to Lincoln. One plank in the Democratic Party platform of that year read, “after four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war,” immediate efforts should be taken to reach a “cessation of hostilities” through negotiation.

Currier and Ives made reference to the “Chicago platform” in The True Peace Commission (1864), which appeared in 1864. It shows Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, back to back, surrounded by Union Generals Philip Sheridan, Ulysses Grant, and William Tecumseh Sherman and Admiral David Farragut. They demand unconditional Confederate surrender, but Sherman adds the conciliatory, “We don’t want your Negroes or anything you have; but we do want and will have a just obedience to the laws of the United States.” Lee responds to the demand of unconditional surrender by proclaiming that he will not surrender but that he is willing to consider an armistice and suspension of hostilities “through the Chicago platform.”

In The True Issue or That’s What’s the Matter (1864), Currier and Ives picture Lincoln and Jefferson Davis having a tug-of-war over a map of the United States. Lincoln proclaims, “No peace without abolition.” Davis responds with, “No peace without separation,” while McClellen stands between them, holding each by the lapel and preventing their further tearing the map. McClellan proclaims, “The Union must be preserved at all hazards.”

By the end of 1864, however, the Union victory at Gettysburg and the siege of Petersburg, as well as Sherman’s March through the South, turned the tide of popular opinion in Lincoln’s favor, and Currier and Ives returned once again to largely pro-Lincoln cartoons. In Desperate Peace Man (1864), Peace Democrat George Pendleton offers Lady Liberty and a slave to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, if only Davis would give him peace in return. McClellan watches approvingly from a distance; a devil-like figure stands behind Davis urging him not to accept the offer but rather to fight on to victory.

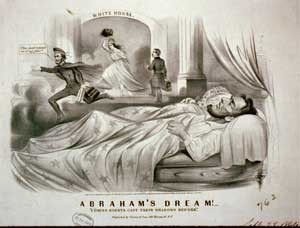

Emancipation remained a divisive issue for the duration of the war, especially in Currier and Ives’s New York City, where news of the proclamation and the draft ignited riots during the summer of 1863. That it remained a campaign issue the next year is seen in Currier and Ives’s Abraham’s Dream: “Coming Events Cast Their Shadows Before” (1864) (fig. 3). In what might be better titled, “Lincoln’s nightmare,” the president is shown sleeping on a bare mattress under a starred sheet, dreaming that he has been defeated in the 1864 election. The figure of Columbia, goddess of liberty and symbol of the nation, stands in the doorway of the White House, brandishing the severed head of a black man, kicking Lincoln out. The disguised Lincoln carries a suitcase and the Emancipation Proclamation and exclaims, “This don’t remind me of any joke,” another reference to Lincoln’s tendency to make untimely jokes. George McClellan, suitcase in hand, climbs the steps to the White House.

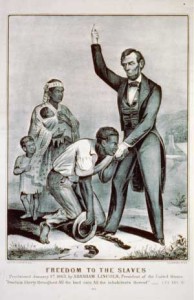

But gradually, especially after Lincoln’s victory in 1864, the successful conclusion to the war a year later, and, of course, his assassination soon thereafter, Currier and Ives pictured the Emancipation Proclamation in a more positive light. Representative are President Lincoln and Secretary Seward Signing the Proclamation of Freedom: January 1st, 1863 (1865) and Freedom to the Slaves (undated) (fig. 4). The latter print is undated. It may have been done as early as 1863, but more likely it appeared after Lincoln’s assassination two years later—or both, as Currier and Ives commonly reissued their more successful prints. Pictured is a slave made free by Lincoln’s proclamation. Hat in hand, he kneels before the Great Emancipator kissing his hand, shackles broken and lying at their feet, while the president gestures for him to rise—perhaps signaling that emancipation was God’s will. The freedman’s wife stands nearby with their two children, one still a babe in arms. The print reads, “Freedom to the Slaves. Proclaimed January 1st, 1863, by Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States. ‘Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants therefore.’ Lev. xxv. 10.”

Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, prompted yet another surge of Union pride. A few prints, The Last Ditch of the Chivalry, or a President in Petticoats , for example, ridiculed Confederate President Jefferson Davis for trying to escape capture dressed in women’s clothing. But once again, Currier and Ives chose not to subject the South to the criticism and demeaning coverage seen in the penny press. Instead, they focused on Lincoln’s assassination and subsequent apotheosis, commonly picturing him coupled with George Washington—one as founder of the nation, the other as its savior.

The portrait Abraham Lincoln: The Nation’s Martyr (1865) was so successful that it was reissued nine times. But nearly as popular were The Assassination of President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre (1865) and The Death Bed of the Martyr President Abraham Lincoln (1865), wherein family, friends, and figures of note gather at the slain president’s bedside.

The Aftermath

After the Civil War, Currier and Ives followed the mood of the nation once again, gradually distancing themselves from emancipation and the Radical Republican plan to “reconstruct” the South. In the years immediately following the war, the company issued prints critical of Southern resistance. By way of example, in Reconstruction, or A White Man’s Government (1868), a white Southerner being swept along in a river toward a waterfall refuses the rescuing hand of a black freedman, saying, “Do you think I’ll let an infernal nigger take me by the hand? No sirree, this is a white man’s government.”

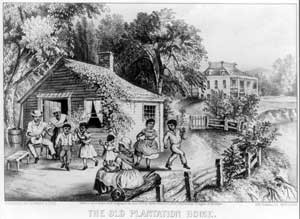

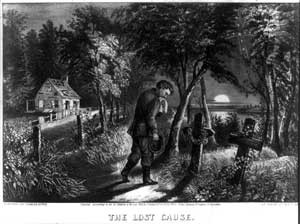

But even at that point, Currier and Ives were increasingly criticizing the Republicans for their Southern policy. In an undated print, likely done in 1868, Fate of the Radical Party, a train powered by a caricatured African American and engineered by Republican leaders Ulysses Grant and Thaddeus Stevens speeds down a track toward a ditch, while President Andrew Johnson frantically tries to fill the hole. The company even began to issue, as it had before the war, idyllic plantation scenes like A Home on the Mississippi (1871) and The Old Plantation Home (1872) (fig. 5). The first shows contented, even carefree, blacks still working the cotton fields. The second pictures them outside their picturesque plantation cabin, cavorting and dancing to the songs played on the banjo. But perhaps the most glaring “change of heart” occurred in 1872, when the company issued The Lost Cause (1872) (fig. 6), an unsigned print wherein a Confederate soldier is shown weeping at a gravesite, a dilapidated cottage standing in the background.

Once again, echoing Northern sentiment, Currier and Ives seemed to forget just why the Civil War was fought and followed the nation toward the era of Jim Crow. From the mid-1870s into the 1890s, the company issued what might well have been its most successful series of prints ever—its Darktown series—which constituted some of the most vicious “race prints” of that or any day. Employing much of the language used at the time, this series consisted of over one hundred individual “comics,” which the company insisted were intended as humor. In these comics, Currier and Ives, as historian William Fletcher Thompson later wrote, “reinforced the widely accepted stereotype that pictured the African American as a kinky-haired, thick-lipped, wide-eyed, simian creature and satirized his or her every attempt to act in a civilized manner.”

Postscript

Currier and Ives succumbed to advances in the technology of reproduction, as well as to changes in American taste, and closed its doors in 1907. Its last prints were issued in 1898 offering scenes from the Spanish American War. The company’s works were soon forgotten—discarded like yesterday’s newspaper, one person put it—only to be rediscovered some thirty years later and valued for very different reasons than those for which they were produced.

Further Reading:

Much of what has been included in this article has been drawn from research done for my book Currier and Ives: America Imagined (Washington, D.C., 2001). The most complete collection of information on Currier and Ives prints is Bernard F. Reilly Jr.’s Currier and Ives: A Catalogue Raisonne (Detroit, 1984). Other useful publications include: Russell Crouse, Mr. Currier and Mr. Ives (Garden City, N.Y., 1936); Harry Peters, Currier & Ives: Printmakers to the American People (Garden City, N.Y., 1929-31); Walton Rawls, The Great Book of Currier & Ives’ America (New York, 1979); and Colin Simkin, Currier and Ives’ America (New York 1952).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.2 (January, 2009).

Bryan F. Le Beau, vice president for academic affairs at the University of Saint Mary, is the author of Currier and Ives: America Imagined, published by Smithsonian Institution Press in 2001.