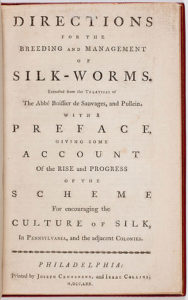

1. Among the reasons it illustrates such extensive networks is that Directions for the Breeding and Management of Silk-Worms, although a published text, is not unlike a commonplace book. Its pages contain writings by men who put ink to paper in London, Philadelphia, Dublin, New Jersey, and France. Enlivened with scattered notations and opinions about the writings gathered within, it is both compilation and distillation. Inside the physical confines of a single binding, it brings together original musings, bits of writing copied from personal letters, and extracts and translations of previously published materials, creating a new, and newly coherent, narrative.

2. Rather than reflect the collecting efforts of a single individual, however, this particular commonplace-like text was created by a group of men. Most probably compiled by a committee of four, it chronicles the work of the newly established American Philosophical Society’s “Silk Society.” Housed within the APS “Committee on Husbandry and American Improvements,” the Silk Society aimed to put Pennsylvania in the vanguard of colonial sericulture. Under the Silk Society’s erudite guidance, Pennsylvania was to become the colony that raised the most silkworms, grew the most mulberry trees to feed them, and harvested the most dead worms’ cocoons to be converted into thread for weaving silk cloth. The society described itself as a “Number of Gentlemen, animated with a Love of their Country” to promote the “raising of silk.” Directions for the Breeding and Management of Silk-Worms was their marketing tract and how-to manual. Alluding to natural history and commerce alike, it sold sericulture as a fascinatingly scientific yet undemanding industry with great economic potential, one of interest to urban natural philosophers and merchants yet simple enough for humble farmwives to understand.

3. Somewhat against common wisdom and the lessons of history (which gave pride of place for colonial North American sericulture to Georgia—never mind the global dominance of China), the Silk Society boasted that “No Country seems better adapted to the raising of silk Worms” than Pennsylvania. As befitted their shared membership in the APS, these men backed their patriotic assertion with science. They used empirical observations about local botany and global geography to argue for the project’s economic viability. Approvingly noting the ready availability of indigenous mulberry trees, they trumpeted that “any person who will cast an eye on a map of the world” must naturally conclude that Pennsylvania “is well adapted to the raising of silk, as lying so nearly in the same climate and latitude” with “the great empire of China” (long and legendarily held, of course, as the source of the world’s best silk).

4. Thus emboldened by their grandiose empirical observations, the Silk Society encouraged Pennsylvanians to cultivate silkworms and bring their cocoons to the public manufactory—a “filature” in the language of the business—they would establish in Philadelphia. In this manufactory, urban workers (otherwise poor and under- or unemployed) would unravel and reel the cocoons harvested by rural laborers (envisioned as mostly women and children). This raw silk would then be exported in skeins across the Atlantic to Britain, where it would be sold for weaving fabric in the London silk industry. A competition for Parliamentary bounties offered to the American colony that produced the largest amount of raw silk added economic incentive. With a conciliatory nod to British wariness about colonial production expressed during the contestation over the Stamp Act five years before, the Silk Society was careful to note that “indeed this design is so far a happy one, that while it promises to be so advantageous to ourselves, it interferes with no commercial interest of the mother country, but on the contrary co-operates with the intention of the Parliament.” The Silk Society’s sericulture project, in other words, was promoted as an “American Improvement” that benefitted the colony and the empire both.

5. In its preface, Directions for the Breeding and Management of Silk-Worms offers a history of itself as a book, as well as of the Silk Society’s project. No less a figure than Benjamin Franklin was pivotal to both these histories. In 1770, when this book was printed, APS founder Franklin was in London, and (if more were needed) this book offers proof of the omnipresence of his impact on colonial natural philosophers regardless of his physical whereabouts. Sericulture was a project dear to Franklin’s heart. He called silk “the happiest of all inventions for cloathing.” He touted its potential for clothing large populations like China’s (and, not coincidentally, like the one he had famously predicted for colonial America in Parliamentary testimony over the Stamp Act). The book highlights his role, offering an interesting glimpse into one of Franklin’s less famous interests. The APS voted to move forward with its sericulture project only “upon a letter being laid before them from Dr. Franklin to one of the members.” In true commonplace fashion, the book includes bits of this private letter, in which Franklin urged the APS to seek political as well as economic backing for the project. The book also includes the textual fruits of his advice: a copy of the APS funding petition to the Pennsylvania Assembly and a list of the upwards of 300 male subscribers who signed up to back the silk-making efforts.

6. It is as a material text that this book best reflects the pragmatic politics and economics behind Franklin’s recommendations and its own publication. An intriguing thing about this otherwise physically mundane text is that the set of pages marked with the signature of “B” comes after those marked “Bb.” Printers used such signature marks to ensure that a book was assembled in the proper order, with “Bb” indicating that the set of pages so marked (called a signature, or a gathering) was meant to follow “B.” This book, then, somewhat unusually reverses the order in which its pages were printed, with the set printed first coming last, and that printed last coming first. Franklin’s letter was received in January, and the APS voted to move forward with their silk project in February, first advertising it in Philadelphia newspapers in April. This book was one of the first to be printed by Isaac Collins and Joseph Crukshank, not long after the two fellow Quakers entered into partnership in Philadelphia in January of that year. As Collins and Crukshank operated together only until that August, this book was compiled sometime in that period, most likely between March and June. Evidently that window of time was not sufficient to gain funding from the Pennsylvania Assembly. With the optimal season for hatching silkworm eggs and harvesting mulberry leaves fast approaching, the Silk Society had to act faster than politicians. Thus they started a private subscription plan to fund the project. The printing of the preface, accordingly, came after the printing of the body of the text. This late preface reflected the pragmatic demands of printing and funding; a delay due to uncertainty over the length of the to-be-added preface, and the desire to publish a complete subscription list as antidote to political lethargy.

7. In addition to Franklin’s letter, the preface includes portions of a letter from “an ingenious” APS member, New Jersey Anglican Reverend Jonathan Odell. Odell was the friend and protégé of Franklin’s illegitimate son, William, then governor of New Jersey. In his letter, Odell describes his work translating the French pamphlets “our worthy friend Dr. Franklin” sent over from London along with his letter, the Mémoires sur l’éducation des vers à Soie (1763) by Abbé Pierre Augustin Boissier de Sauvages. The French Catholic cleric shared Franklin’s keen interest in the scientific study of sericulture and its economic possibilities (in the abbé’s case, of course, for Britain’s traditional enemy, the kingdom of France). That Odell, an Anglican minister, translated the works of a Catholic cleric is a fitting reminder of the links between religion and sericulture. Early modern people on both sides of the Atlantic found evidence of God’s work in sericulture. They marveled at the silkworm’s metaphorical possibilities, praising the wonderment of such a dumpy, ugly creature creating one of man’s most elegant textiles. Such beauty emerging from such ugliness was seen as “an emblem” of an “adorable Lord and Saviour,” reminder of a God who clothed man in the shining raiment of eternal life after the imperfect mortal body died. Despite its religious associations, Odell complained of the work, calling it “an endless task,” because the “Abbé is tedious, minute and philosophical.” What is published in Directions for the Breeding and Management of Silk-Worms is, one senses, Odell’s decidedly frustrated and accordingly loose (condensed from hundreds of “tedious” pages to seventeen) summary of a less than word-for-word translation of Boissier de Sauvages.

8. The imprecision of Odell’s translation probably did not trouble his readers. Franklin’s inclusion of Boissier de Sauvages’ treatise with his private letter indicates that neither the Library Company of Philadelphia (another Franklin-founded Philadelphia institution) nor an APS member owned it, meaning that the French text was not readily available in the colonies. By contrast, the other treatise on sericulture summarized in the book—one by yet another cleric, Irish Anglican Reverend Samuel Pullein—was both widely available and popular. Extracts of Pullein’s The culture of silk, or, An essay on its rational practice and improvement … for the use of the American colonies (1758) were even printed on the front page of colonial newspapers. With their version of Pullein, the book’s authors managed to outdo Odell’s skills at dramatic textual reduction by extracting a mere eleven pages from his nearly 300-page work. Pullein was popular among women readers as well as men. Pennsylvanian Sabina Rumsay recorded her successful sericulture efforts after reading Pullein in a letter the APS reprinted as far afield as the Boston Chronicle. And Pullein was discussed in private colonial correspondence among women. Eliza Lucas Pinckney and her daughter, for example, both wrote to friends about using Pullein in sericulture efforts on their South Carolina plantation—efforts conducted, of course, through the labor of their slaves. Such female involvement in sericulture was not unusual. In fact, the Silk Society began its book by tracing the history of sericulture from its first, ancient efforts by its “inventress” on “the island of Cos.” Another woman, Susanna Wright, who pioneered sericulture in Pennsylvania and even wrote her own treatise on the subject, won the 1771 contest for silk production advertised in the Silk Society’s book.

9. Not surprisingly, given the historical prevalence of women in sericulture, the Silk Society’s book offers examples of how those officially marginalized in global knowledge networks of learned men (like women and colonists) did, in fact, actively contribute to them. It also offers insight into the importance of creolized knowledge in the Atlantic World. Odell’s goal was to “elucidate the French treatises” of Boissier de Sauvages with “adaptations and notes particular to our own climate.” Adapting the abbé’s advice to suit an American rather than a European climate and audience, Odell’s synopsis offers “asides” specific to “this Province,” and sprinkles in local aphorisms (as, for example, when cautioning against exposing mulberry leaves to frostbite by citing “an Indian proverb which says, that ‘winter seldom rots in the sky:’ the meaning of which is obvious, that sooner or later we must expect to feel our share of cold”). Odell’s localized approach was in keeping with accepted knowledge that sericulture was production that benefitted from on-the-spot empirical observation—even from women involved in it. The Silk Society, in fact, used their book to entreat locals to share their experience—particularly that “better adapted to this climate and country than what are delivered” in the European texts.

10. In the end, like so many colonial sericulture efforts before it, the Silk Society’s efforts did not come to much. Pennsylvania did not, as the APS hoped, outstrip Georgian silk production (much less that of China). This little book, then, is testament to a moment of shared optimism about a grand plan that would ultimately fail. It also hints at a far grander North American plan that would soon fail: that of the British Empire. Despite pointed assurances to the contrary, the Silk Society’s project contained seeds of American competition with Britain within it (as its champion, Franklin, most assuredly knew). After all, Franklin had testified before Parliament during the Stamp Act Crisis that “with a little industry” Americans could make cloth “at home.” During the Revolution, Franklin’s daughter would send him material proof of the colonial manufacturing possibilities within the Silk Society’s project. In 1778, she shipped twenty-two yards of homespun silk woven from Pennsylvania silkworms to him in France to present to Queen Marie Antoinette, evidence that Boissier de Sauvages had been used to good effect.

Like the empire, the men who came together within its pages would break apart. Odell, like his friend William Franklin, would become estranged from William’s father, Benjamin, and eventually leave the country. Before he went, he would use his literary skills to write fiercely satirical Loyalist verse under the pen name “Britannicus.” It hardly needs mentioning that Franklin would pick up his pen in the opposite cause.

Further Reading

To date, the best work on colonial sericulture efforts focuses on the South. See work by Ben Marsh such as “Silk Hopes in Colonial South Carolina” in The Journal of Southern History 78:4 (November 2012). Marsh’s forthcoming book, Unraveling Dreams: Silkworms and the Atlantic World, c. 1500-1840 (University of Georgia Press) also promises to add a great deal to colonial sericulture history. Also see the introductory section of Jacqueline Field, Marjorie Senechal, and Madelyn Shaw, American Silk, 1830-1930: Entrepreneurs and Artifacts (Lubbock, Texas, 2007). For work that considers colonial sericulture within the larger context of American husbandry projects and Enlightenment thought on progress, see Joyce Chaplin, An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation and Modernity in the Lower South, 1730-1815 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1993). For what is perhaps the best look at how colonists (men and women both) contributed to Atlantic world natural history networks, see Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006). To gather biographical details on early American printers, visit the Printers’ File at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Mass., which provides an invaluable factual starting point (special thanks are due to the curator of that record system, Ashley Cataldo, as well as to AAS Curator of Books, Elizabeth Watts Pope, who both provided invaluable expertise and assistance for this piece). Biographical studies exist for some of the key players in the making of Directions for the Breeding and Management of Silk-Worms. See Whitfield J. Bell Jr., Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society, Volume One, 1743-1768, Memoirs of the APS, Memoir 226 (Philadelphia, 1997). For more on Odell, see Cynthia Dubin Edelberg, Jonathan Odell: Loyalist Poet of the American Revolution (Durham, N.C., 1987). For more on Collins, see Richard F. Hixson, Isaac Collins: A Quaker Printer in Eighteenth-Century America (New Brunswick, N.J., 1968). For more on Franklin, see WorldCat.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.1 (Fall, 2013).

Zara Anishanslin is assistant professor of history at the College of Staten Island/City University of New York. Her first book, a history of the eighteenth-century British Atlantic world told through the single portrait of a colonial woman in a silk dress, is forthcoming from Yale University Press.